Ritual dance is such a pervasive aspect of First Society life that it too must have left Africa some 60,000 years ago as an essential—and already by then well-deflned—aspect of the human cultural package. In many cases, the dance is part of a larger ceremonial event. It is important to stress the concept of ceremonialism to draw emphasis away from the tendency to see dance as an autonomous event or as a form of entertainment. In Australia and the Americas in particular, ceremonies consist of a number of related events that may even involve different performance grounds belonging to different clans. A ceremony may attract, by invitation, participants from neighboring and even distant communities. Some ceremonies are seasonal, but others can be related to the death of an important flgure, or to certain shamanistic requirements.

The Hazda have a sacred dance ceremony that takes place every night when there is no moon in the sky. In other words, it is done in complete darkness. Once it has been dark for a while, people begin to assemble in the open area in the camp. The men congregate in one

Figure 1.46: Men and women of the Karo tribe gather for an evening dance, Dus, Omo Valley, Ethiopia. Source: Randy Olson/National Geographic Stock

Area and the women elsewhere. Only one man dances at a time, wearing a black cape and headdress of black and brown ostrich feathers, with tie bells on his ankles and holding a seed-filled gourd as a shaker. These objects are considered sacred. The man dances by stomping very hard on the ground, providing a slow, steady beat with the jangling of the bells and the shaking of the gourd. He sings in a call-and-shout style and sometimes whistles. He will dance a minute or two, then disappear to return to dance a bit longer. With each return, the women who answer his singing become more animated in their responses. Eventually they too will get up and dance around the man, whom they can only hear or whose shape they can vaguely intuit in the darkness. When the man finishes, he passes the ritual over to the next man and the same thing occurs again, until all the men have danced.77 Night-time dances are typical and still practiced by the Karo in Ethiopia, for example (Figure 1.46).

In more complex First Societies, these types of dances ofi:en featured ritual acts of gift giving, which served to affirm the identity of the group and establish the link between the humans and the non-humans. And since songs are often considered to have been made by the spirit world, it was the duty of humans to transmit them as accurately as possible to the next generation. Ceremonies also served as venues for social interaction with distant communities. Though ceremonies have a particular script that does not mean that First Society people never wavered from tradition. From early contact with Native Americans in the United States and with First Society peoples in Australia it is clear that ceremonies could change over time. Some, for example, were adopted from surrounding cultures as the influence of those cultures spread.78

Dances often feature elaborate sacred costumes and headgear, either worn or carried by the dancers. In Australia, the gear can represent rainbows, pelicans’ bills, shields or ha! angan spirits of a deceased person, among other things. In the Americas they can represent birds, bison, and a whole range of animals. Some dances are intended to help make contact

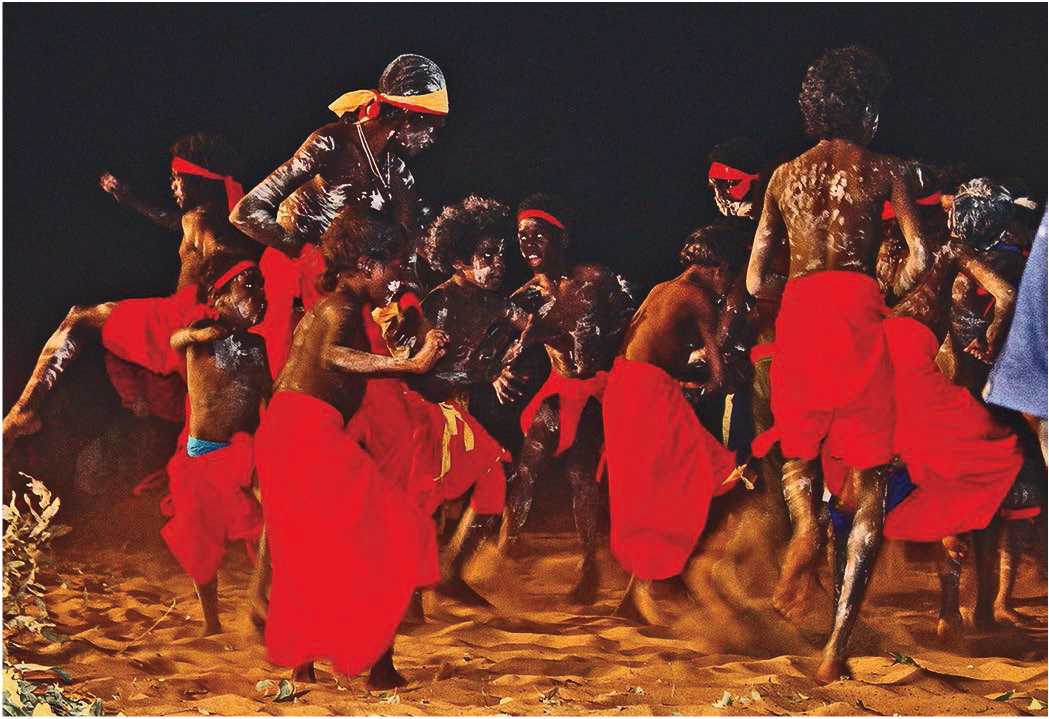

Figure 1.47: Night-time ceremony, Australia. Source: Luca De Giglio

With the spirit world through an altered state of consciousness brought on by the dance itself. In some places the dances were more athletic than others, but they were rarely short events. A dance can last through the entire night; some can be part of ceremonies that last for several days, and occasionally even weeks (Figure 1.47). Some mark seasonal transitions, others the transitions in the human life cycle. For the Zuni in the American Southwest, a dance ceremony includes speeches made by the chief that take six hours to deliver, and which he has to learn by heart.79

In some places the difference between men and women singing and dancing is not sharply drawn. But in Arnhem Land in Australia, this is not the case. Men’s dancing is athletic with high leaps, vigorous and strongly differentiated movements, and skillful imitation of bird and animal behavior. Women’s dancing is more restricted to standardized postures and hand and foot movements. In north-central Arnhem Land one finds circle dancing and fluid rhythmic movement, similar to the stomp dance in the Americas where dancers, male and female, move counterclockwise around a sacred fire. In Australia, the posture is often a semi-crouching position with knees apart and trunk forward and arms flexed.

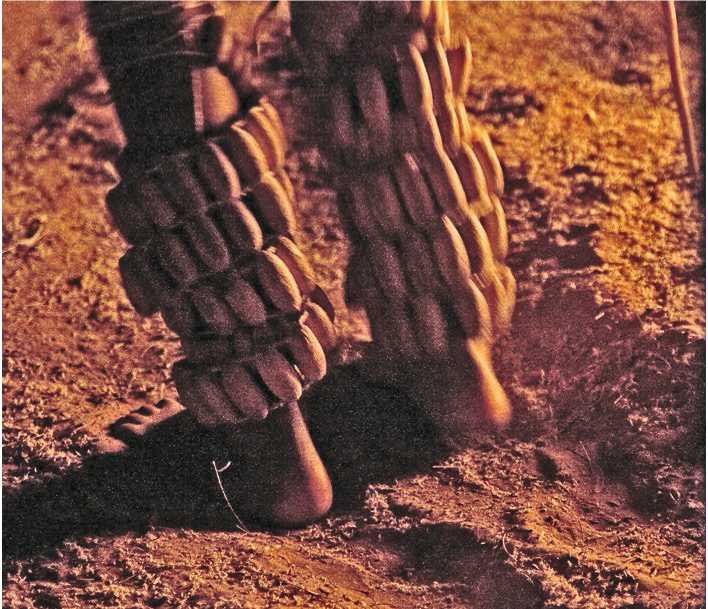

Dances are usually performed on specially prepared ground, either in the area of the camp or nearby, depending on the context of the occasion (Figures 1.48 and 1.49). In Australia, a bough-shade is usually erected on the side of the performance ground. In this shade, the objects to be used are prepared and the dancers are decorated. These preparations, which can be quite time consuming, are integral to the event and are accompanied by songs summoning the spirits to ensure the efficacy of the event. Similar preparations are to be found among the Native Americans. In most cases, in fact, the boundary between preparation and the actual dance are imperceptible so that the whole event is a gradual building up to a climax. Endings, however, are usually abrupt, signaled by the removal of the dancers’ headdresses and decorations.

Figure 1.48: Ankle rattles made of shells at a tribal dance in the Kalahari Desert, Botswana. Source: © Ben Lai (Http://creativecommons. org/licenses/ by-sa/3.0/deed. en)

Figure 1.49: Tribal dance in Borneo, Malaysia. Source: © Aruna (Http://cre-ativecommons. org/licenses/by-sa/2.5/)

Figure 1.50: Yupik Eskimo women at a drum dance, Provid-eniya, Siberia, Russia. Source: B & C Alexander/ArcticPhoto

In places where it is cold, these events are held indoors (Figure 1.50). Such dances will have more restricted movements and are sometimes done in a seated position. The Inuits, along the Arctic Circle, constructed a special structure, known as kashim, for their ceremonial dances, shamanistic healings, yearly meets, and initiation rites. Rectangular in Alaska, and more circular in eastern areas, they were partially dug into the ground and had a roof of logs and earth supported by timber posts. Ten or more meters across, they could hold at least a hundred people. Larger villages might have had more than one. Some had elaborate venting for the fire in which a channel was dug from just outside the entrance under the floor to the fire pit. This prototype can be found in Siberia all the way to Peru. To enter the kashim, a person had to crawl on all fours through the low entry, which, apart from trapping the warm air inside, served as a reminder of the animal-human transformation. The smoke hole represented the upper world, the fire pit the lower world, and the ceremonial house the human world. The ability of the spirits to “enter” and “exit” from both fire pit and smoke hole made this interaction explicit.

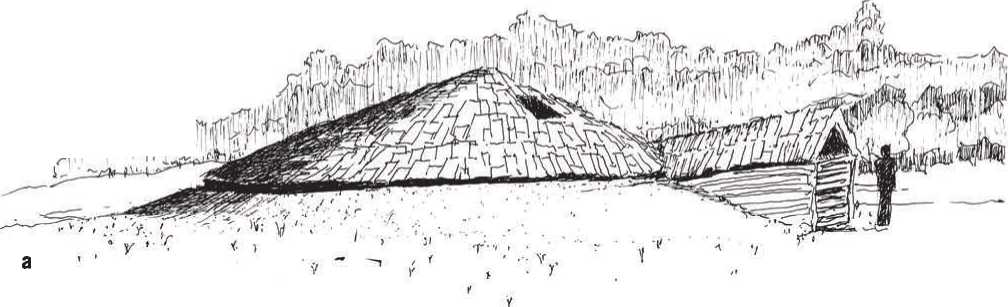

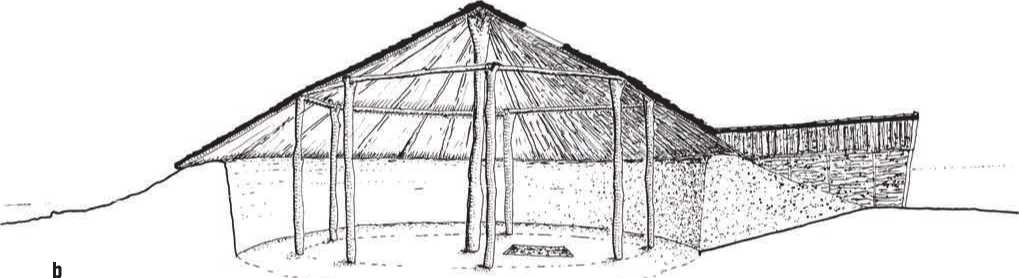

The Washoe, who lived in the mountains around Lake Tahoe in California, also built special Dance Houses. First an area 10 meters in diameter and about a meter deep was excavated; above this a 3.5-meters-high, conically shaped structure of poles covered by earth and tule mats was created (Figure 1.51a and 1.51b). The fireplace was at the center and the entrance faced to the east. They were built primarily to assist a person transitioning into a shaman or for ceremonies to expel evil spirits.80 The central post of the structure received at its apex the accumulated tips of the roof poles. Between the center post and the outer walls was a ring of seven posts. The structure carried a host of short poles on which is piled earth,

Tule, and brush. The entranceway sloped down from the outside and was about 1.2 meters wide. The rectangular smoke hole was over the fireplace and between the entrance and the center pole. The floor was covered with fresh green willow boughs and leaves. This design, known as a pit house or earth lodge, was widespread and can be found from Siberia into Peru, with numerous local variants, as we shall discuss later, in the case of a sacred dance, the dark outer circle was occupied by the onlookers, who sat or reclined with their feet toward the center. The performers assembled near the entrance and when ready ran through the entrance and grouped themselves on the western side of the house, beating time by striking the ground vigorously with the feet and singing or blowing low musical strains on whistles made of goose or eagle bones. At intervals, the chief climbed the roof and sang a chant. These ceremonies could last up to four days.

Figure 1.51a, b: Typical Pawnee dance house, Nebraska, USA: (a) view, (b) section. Source: Mark Jarzombek & Timothy Cooke/C. Hart Merrian, Studies of Caiifornia Indians (Berkeiey: University of Caiifornia Press, 1955), 13.

M

Even in warm climates a special Dance House may be erected. The Ava Chiripa, who live in the rainforests of Paraguay, for example, have a ceremony called nemboe kaaguy, or the Prayer of the Forest. The Dance House, situated in the center of the village, is about 6 by 4 meters, larger than the ordinary house, and has one side that is open and facing east. In front of this space, a large trough made of sacred cedar is placed that holds the ceremonial drink. The trough is in the shape of a canoe. In front of it there are three cedar posts, about 1.2 meters high. The two outer ones hold candles. Feathers and an arrow ornament the central post. The ceremony lasts for four days, with ritual dances taking place in front of the trough and the posts. As the days go on, more and more people from the surrounding areas show up to participate. The ceremony ends with the drink being imbibed first by the shaman and then by the rest of the people, who all dance in circles and crisscrossing groups of men and women. The date for the ceremony is determined by the dream of the highest-ranking shaman responsible for the ritual, but usually takes place as a ritual inauguration of the first fruit and harvest.82

Perhaps of all the activities that came out of Africa, dance, despite the fact that it leaves only the most intangible of traces, was the most important. Its capacity to bond humans both to one another and to the cosmos—while at the same time linking them across the difierences of space, time, and even language—is enormous. Dancing was the glue that held everything together.

An anthropologist studying the Mbuti in the Congo rainforest was once taken on expedition to collect honey. One evening, when everyone was back in the camp, he noticed a man dancing by himself. The anthropologist asked him why he was dancing alone. “He stopped, turned slowly around and looked at me as though I was the biggest fool he had ever seen; and he was plainly surprised by my stupidity. ‘But I’m not dancing alone,’ he said. ‘I am dancing with the forest, dancing with the moon.’” 83

ENDNOTES

1. Scholarly literature uses a complex series of terms to designate the development of difierent cultures through time. In Africa: Early Stone Age (2.5 million to 200,000 bp); Middle Stone Age (200,000 to

20.000 bp); and Later Stone Age (20,000 bp to Present). In Europe: Lower Paleolithic (750,000 to

220.000 bp); Middle Paleolithic (220,000 to 45,000 bp); and Upper Paleolithic (45,000 to 10,000 bp). In India: Paleolithic (500,000 to 30,000 bp); Mesolithic (30,000 to 5000 bp); and Neolithic (8000 to 1500 bp). Because of these variants and the difierent time slots associated with them, I have decided to not use these terms in the book, in the hope that these terminological issues can be addressed in other contexts.

2. Shannon P McPherron et al., “Evidence for Stone-Tool-Assisted Consumption of Animal Tissues Before 3.39 Million Years Ago at Dikika, Ethiopia” Nature 466 (August 12, 2010): 857-860.

3. Anna J. Machin, R. T. Hosfield, and S. J. Mithen, “Why Are Some Handaxes Symmetrical? Testing the Influence of Handaxe Morphology on Butchery Efliectiveness,” Journal of Archaeological Science 34, no. 6 (June 2007): 883-893.

4. Eileen M. O’Brien, “What Was the Acheulean Hand Axe?” The MCC Hominid Journey, Http://www. mesacc. edu/dept/d10/asb/origins/hominid_journey/handaxes. html (accessed July 2, 2011). See also: William H. Calvin. William H. Calvin, “The Unitary Hypothesis: A Common Neural Circuitry for Novel Manipulations, Language, Plan-ahead, and Throwing?” in Tools, Language, and Cognition in Human Evolution, eds. Kathleen R. Gibson and Tim Ingold (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993): 230-250.

5. M. D. Leakey, Olduvai Gorge Volume 3; Excavations in Beds I and II, 1960-1963 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1971): 24, Illustration 7. For an Acheulean site in Israle, see: Nira Alperson-Afil, Gonen Sharon et al., “Spatial Organization of Hominin Activities at Gesher Benot Ya’aqov, Israel,” Science, New Series, 326/ 5960 (December 18, 2009): 1677-1680.

6. V. N. Misra, “Middle Pleistocene Adaptations in India,” in The Pleistocene Old World; Regional Perspectives, ed. Olga Soflier (New York: Plenum Press, 1987): 99-119.

7. Karl W. Butzer, “A Settlement Archaeology Project in the Alexandersfontein Basin, Kimberly,” Palaeoecology of Africa 9 (1976): 144-145.

8. Kathleen Kuman, Moshe Inbar, and R. J. Clarke, “Palaeoenvironments and Cultural Sequence of the Florisbad Middle Stone Age Hominid Site, South Africa,” Journal of Archaeological Science 26, no. 12 (December 1999): 1409-1425.

9. C. Garth Sampson, The Middle Stone Age Industries of the Orange River Scheme Area (Bloemfontein: National Museum, 1968): 24-27; C. Garth Sampson, The Stone Age Archaeology of Southern Africa (New York: Academic Press, 1974), 169.

10. See Curtis W Marean et al., “Early Human Use of Marine Resources and Pigment in South Africa During the Middle Pleistocene,” Nature 449 (2007): 905-908. Sally McBrearty and Alison S. Brooks, “The Revolution That Wasn’t: A New Interpretation of the Origin of Modern Human Behavior” Journal of Human Evolution 39 (2000): 453-563.

11. Christopher S. Henshilwood et al., “Middle Stone Age Shell Beads from South Africa,” Science 304, no. 5669 (April 16, 2004): 404; F. d’Errico et al, “Nassarius Kraussianus Shell Beads from Blombos Cave: Evidence for Symbolic Behaviour in the Middle Stone Age,” Journal of Human Evolution 48, no. 1 (January 2005): 3-24.

12. P. Beaumont and A. Boshier, “Mining in Southern Africa and the Emergence of Modern Man,” Optima 4 (March 1972): 19-29.

13. Paul Pettitt, “The Living as Symbols, The Dead as Symbols, Problematising the Scale and Pace of Hominin Symbolic Evolution,” in Homo Symbolicus: The Dawn of Language, Imagination and Spirituality, eds. Christopher Stuart Henshilwood and Francesco D’Errico (Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing, 2011): 143.

14. James R. Walker, The Sun Dance and Other Ceremonies of the Oglala Division of the Teton Dakota, Anthropological Papers of the Museum of Natural History Volume 16, Part 2 (New York: 1917): 155.

15. Camilla Power, “Women in Prehistoric Rock Art,” in New Perspectives on Prehistoric Art, ed. Gunter Berghaus (London: Praeger, 2004): 75-103; Hans-Joachim Heinz, “The Social Organisation of the !Ko Bushmen” (Master’s Thesis, University of South Africa, 1966): 123.

16. Roger L. Hewitt, Structure, Meaning and Ritual in the Narratives of the Southern San (Hamburg: Buske, 1986): 281; J. David Lewis-Williams, Believing and Seeing: Symbolic Meanings in Southern San Rock Paintings (London: Academic Press, 1981): 51.

17. Ian Watts, “The Origin of Symbolic Culture,” in The Evolution of Culture, eds. Robin Dunbar, Chris Knight, and Camilla Power (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1999): 133.

18. Megan Biesele, Women Like Meat (Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press, 1993): 163, 196.

19. P. B. Beaumont and F. and A. Thackeray, “An Ochre-Mine Near Postmasburg,” The South African Archaeological Society Newsletter 4/1 (June 1981): 2.

20. Diego Salazar, D. Jackson, J. L. Guendon, H. Salinas, D. Morata, V. Figueroa, G. Manriquez, and V. Castro, “Early Evidence (ca. 12,000 BP) for Iron Oxide Mining on the Pacific Coast of South America.” Current Anthropology 52, no. 3 (June 2011): 463-475.

21. I would like to thank the archaeologist Sheila Dawn Coulson for discussing this site with me. See also Yngve Vogt, “World’s Oldest Ritual Discovered. Worshipped the Python 70,000 Years Ago,” Apollon Arkeologi, Trans. Alan Louis Belardinelli, published November 30, 2006, Www. ApoIlon. Uio. No/Vis/Art/2006_4/Artikler/Python_English (accessed July 2, 2011).

22. M. L. Murphy et al., “Prehistoric Mining of Mica Schist at the Tsodilo Hills, Botswana,” Journal of the Southern African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy (May 1994): 87-92.

23. A. G. Sagona and J. A. Webb, “Toolumbunner in Perspective,” Bruising the Red Earth: Ochre Mining and Ritual in Aboriginal Tasmania, ed. Antonio Sagona (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1994): 139.

24. See the studies in Frank W Marlowe, The Hadza: Hunter-Gatherers of Tanzania (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010): 225-254.

25. Iain Davidson and W. Noble, “Why the First Colonisation of the Australian Region is the Earliest Evidence of Modern Human Behavior,” Archaeology in Oceania 27 (1992): 138.

26. Richard B. Lee, Irven DeVore, and Jill Nash, Man the Hunter (Chicago: Aldine, 1968).

27. Ronald M. Berndt and Catherine H. Berndt, Man, Land & Myth in North Australia: The Gunwinggu People (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 1970).

28. Salish-Pend d’Oreille Culture Committee, The Salish People and the Lewis and Cark Expedition (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2005): 52.

29. Ann Fienup-Riordan, Boundaries and Passages: Rule and Ritual in Yup’ik Eskimo Oral Tradition (Tulsa: University of Oklahoma Press, 1994): 23, footnote 4. See also page 14.

30. Vishvajit Pandya, Above the Forest: A Study of Andamanese Ethnoanemology, Cosmology, and the Power of Ritual (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1993): 111.

31. Wilhelm Dupre, Religion in Primitive Cultures: A Study in Ethnophilosophy (The Hague: Mouton, 1975): 153.

32. Ann Fienup-Riordan, Boundaries and Passages: Rule and Ritual in Yup’ik Eskimo Oral Tradition (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1994): 50.

33. Bruce D. Bonta, Peaceful Peoples: An Annotated Bibliography (Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow, 1993): 2931, 42; Donald F. Thomson, “The Seasonal Factor in Human Culture,” Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 5, no. 2 (1939): 209-211.

34. Ernest S. Burch, Jr., Social Life in Norwest Alaska, The Structure of Inupiaq Eskimo Nations (Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press, 2006): 29, footnote 1.

35. Michael R. Rampino and Stephen Self, “Bottleneck in the Human Evolution and the Toba Eruption,” Science 262, no. 5142 (December 24, 1993): 1955.

36. It is generally assumed that western Australia was occupied around 40,000 bp, Tasmania around

35,000 bp, and central Australia around 27,000 bp. For a general overview, see Harry Lourandos, Continent of Hunter-Gatherers: New Perspectives in Australian Prehistory (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997).

37. See Jim M. Bowler, “Recent Developments in Reconstructing Late Quaternary Environments in Australia,” in The Origins of the Australians, eds. R. L. Kirk and A. G. Thorne (Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, 1976)L 55-80.

38. Steve Webb, The First Boat People (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 229.

39. See H. Johnston, “Pleistocene Shell Middens of the Willandra Lakes,” in Sahul in Review: Pleistocene Archaeology in Australia, New Guinea and Island Melanesia, Occasional Papers in Prehistory 24, eds. M. A. Smith, M. Spriggs, and B. Fankhauser (Canberra: 1993): 197-203; H. Johnston and P. Clark, “Willandra Lakes Archaeological Investigations 1968-98,” Archaeology in Oceania 33, no. 3 (1998): 105-119.

40. Steve Webb, Matthew L. Cupper, and Richard Robins, “Pleistocene Human Footprints from the Willandra Lakes, Southeastern Australia,” Journal of Human Evolution 50, no. 4 (2006): 405-413.

41. Paul Mellars, The Neanderthal Legacy: An Archaeological Perspective from Western Europe (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1996): 287.

42. Jan Kolen, “Hominids without Homes,” in The Middle Paleolithic Occupation of Europe, eds. Wil Roebroeks and Clive Gamble (Leiden, The Netherlands: University of Leiden Press, 1999): 156.

43. Mikhail V. Anikovich, “Early Upper Paleolithic Industries of Eastern Europe,” Journal of World Prehistory 6, no. 2 (1992): 205-245; A. A. Sinitsyn, “A Palaeolithic ‘Pompeii’ at Kostenki, Russia,” Antiquity 77, no. 295 (2003): 9-14. The site as associated with the Kosteni-Willendorf Culture that spanned central Europe and the Russian plain dating to ca. 30,000-20,000 bp. It is also often equated with the Eastern Gravettian Culture.

44. Ben J. Wallace, Village Life in Insular Southeast Asia (Boston: Little Brown and Co., 1971): 86.

45. Alexander Marshack, Notation dans les Gravures du Paleolithique Superieur (Bordeaux: Delmas, 1970). See also Alexander Marshack, “Cognitive Aspects of Upper Paleolithic Engraving,” Current Anthropology 13, no. 3-4 (1972): 445-477.

46. Alexander Marshack, The Roots of Civilization: The Cognitive Beginnings of Man’s First Art, Symbol, and Notation (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1972): 50-52.

47. Panagiotes Karkanas et al., “The Earliest Evidence for Clay Hearths: Aurignacian Features in Kli-soura Cave 1, Southern Greece” Antiquity 78, no. 301 (2004): 513-525.

48. Steve Brill and Evelyn Dean, Identifying and Harvesting Edible and Medicinal Plants in Wild (and Not So Wild) Places (New York: Harper, 1994): 69-70. See also Harriet V Kuhnlein and Nancy J. Turner, Traditional Plant Foods of Canadian Indigenous Peoples: Nutrition, Botany and Use (Amsterdam: Gordon and Breach, 1991).

49. Christopher Chippindale and Paul S. C. Taqon, The Archaeology of Rock-Art (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998). See also David S. Whitley, ed., Handbook of Rock Art Research (Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press, 2001).

50. Vishvajit Pandya, Above the Forest: A Study of Andamanese Ethnoanemology, Cosmology, and the Power of Ritual (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1993): 126.

51. Harry W. Crosby, The Cave Paintings of Baja California (San Diego, CA: Sunbelt Publications, 1997).

52. Malangine Cave in Australia Is thought to Date to 28,000 bce. Robert G. Bednarik, “The Speleothem Medium of Finger Flutings and Its Isotopic Geochemistry,” Artefact 22 (1999): 49-64.

53. Robert G. Bednarik et al., “Preliminary Eesults of the EIP [Early Indian Petroglyphs] Project,” Rock Art Research 22, no. 2 (2005): 147-197; James Harrod, “Comment on Early Indian Petroglyphs Project,” Rock Art Research 23, no. 1 (2006).

54. Daniel Arsenault, “Spiritual Places in the Algonkian Sacred Landscape,” in Pictures in Place: The Figured Landscapes of Rock-Art, eds. Christopher Chippindale and George Nash (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004): 30-33.

55. Charles P Mountford, “The Artist and His Art in an Australian Aboriginal Society,” in The Artist in Tribal Society: Proceedings of a Symposium Held at the Royal Anthropological Institute, ed. Marian W Smith (New York: Free Press of Glencoe, 1961): 4.

56. The long epic poem The Mahdbhdrata, composed between the fifth century bce and the fourth century ce, is a key source for ancient Indian festivals and celebrations.

57. Hitoshi Miyake, Shugendo: Yamabushi no rekishi to shiso (Higashimurayama: Kyoikusha, 1978): 45-52.

58. Milton M. R. Freeman, Endangered Peoples of the Arctic: Struggles to Survive and Thrive (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2000): 63.

59. Laurel Kendall, Shamans, Nostalgias, and the IMF: South Korean Popular Religion in Motion (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2009): 184-186.

60. Miguel Albero Bartolome, “Shamanism Among the Ava-Chiripa,” in Spirits, Shamans, and Stars: Perspectives from South America, eds. David L. Browman and Ronald A. Schwarz (The Hague: Mou-ton, 1979): 95-148.

61. A. T. Murray, Homer: The Odyssey (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1975): 10.302-10.303.

62. “Lakota Words” and “Apache Words,” Frontierland, Http://kayitah. tripod. com/page2.html (accessed January 28, 2012).

63. See John R. Swanton, Creek Religion and Medicine (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2000); Tis Mal Crow, Native Plants, Native Healing, Traditional Muskogee Way (Summertown, TN: Native Voices Book Publishing Co., 2001); James H. Howard and Willie Lena, Oklahoma Seminoles: Medicine, Magic and Religion (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1984); Alice Micco Snow and Susan Enns Stans, Healing Plants: Medicine of the Florida Seminole Indians (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2001).

64. Agnes Kerezsi, “Similarities and Differences in Eastern Khanty Shamanism,” in Shamanism and Northern Ecology, ed. Juha Pentikainen (Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 1996): 194-195.

65. This is the argument of A. P. Elkin, Aboriginal Men of High Degree (New York: St. Martin Press, 1978).

66. Michael Harner, The Jivaro: People of the Sacred Waterfall (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1973).

67. Johannes Wilbert, “Magico-religious Use of Tobacco Among South American Indians,” in Spirits, Shamans, and Stars: Perspectives from South America, eds. David L. Browman and Ronald A. Schwarz (The Hague: Mouton, 1979): 13-38.

68. Alfred L. Kroeber, The Religion of the Indians of California (Berkeley: University Press, 1907). See also Jean Blodgett, The Coming and Going of the Shaman: Eskimo Shamanism and Art (Winnipeg: Winnipeg Art Gallery, 1979).

69. See Richard B. Lee, The Dobe! Kung (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1984): 104-118.

70. Walther Heissig, The Religions of Mongolia, trans. Geoffrey Samuel (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980): 6-23.

71. Nicholas J. Saunders, “Stealers of Light, Traders in Brilliance: Amerindian Metaphysics in the Mirror of Conquest,” Anthropology and Aesthetics, no. 33 (Spring 1998): 225-252.

72. For an excellent overview see Carmen Blacker, The Catalpa Bow: A Study of Shamanistic Practices in Japan (London: Allen & Unwin, 1975).

73. Sonoda Minoru, “The State Cult of the Nara and Early Heian Periods,” in Shinto in History: Ways of the Kami, eds. John Breen and Mark Teeuwen (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2000): 47-67.

74. Nelly Naumann, “Whale and Fish Cult in Japan: A Basic Feature of Ebisu Worship,” Asian Folklore Studies 33 (1974): 1-15.

75. See “Core Shamanism and Neo-Shamanism,” in Shamanism: An Encyclopedia of World Beliefs, Practices, and Culture, Volume 1, eds. Mariko Namba Walter, Eva Jane, and Neumann Fridman (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2004): 49-57.

76. Susan Starr Sered, Women of the Sacred Groves: Divine Priestesses of Okinawa (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999): 3.

77. Frank W Marlowe, The Hadza: Hunter-Gatherers of Tanzania (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010): 59-60.

78. Robert H. Lowie, “Ceremonialism in North America,” American Anthropologist 16, no. 4 (Oct. - Dec., 1914): 602-631; 612 and 616.

79. Edmund Wilson, Red, Black, Blond, and Olive: Studies in Four Civilizations: Zuhi, Haiti, Soviet Russia, Israel (New York: Oxford University Press, 1956): 33.

80. Edgar E. Siskin, Washo Shamans and Peyotists: Religious Conflict in an American Indian Tribe (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1983): 40-42.

81. C. Hart Merrian, Studies of California Indians (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1955): 3032.

82. Miguel Albero Bartolome, “Shamanism Among the Ava-Chiripa,” in Spirits, Shamans, and Stars: Perspectives from South America, ed. David L. Browman and Ronald A. Schwarz (The Hague: Mou-ton, 1979): 136-137.

83. Colin M. Turnbull, The Forest People (New York: Doubleday, 1962): 285.

World History

World History