Early European scholars tried to systematically classify Homo sapiens into subspecies, or races, based on geographic location and phenotypic features such as skin color, body size, head shape, and hair texture. The 18th-century Swedish naturalist Carolus Linnaeus originally divided humans into subspecies based on geographic location and classified all Europeans as “white,” Africans as “black,” American Indians as “red,” and Asians as “yellow.”

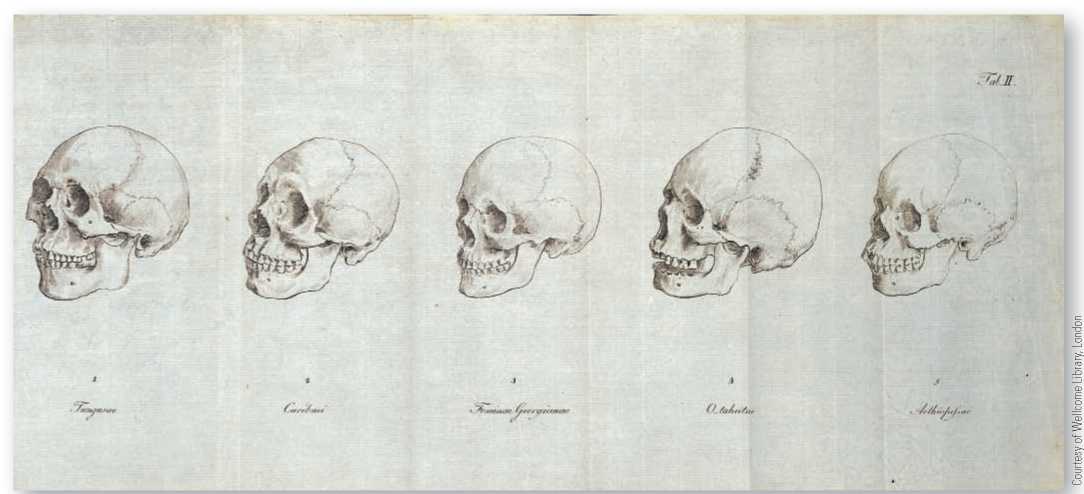

The German physician Johann Blumenbach (17521840) introduced some significant changes to this four-race scheme with the 1795 edition of his book On the Natural Variety of Mankind. Most notably, this book formally extended the notion of a hierarchy of human types. Based on a comparative examination of his human skull collection, Blumenbach judged as most beautiful the skull of a woman from the Caucasus Mountain range (located between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea of southeastern Europe and southwestern Asia). The skull was more symmetrical than the others, and he saw it as a reflection of nature’s ideal form: the circle. Surely, Blumenbach reasoned, this “perfect” specimen resembled God’s original creation. Moreover, he thought that the living inhabitants of the Caucasus region were the most beautiful in the world. Based on these criteria, he concluded that this high mountain range, not far from the lands mentioned in the Bible, was the place of human origins.

Blumenbach concluded that all light-skinned peoples in Europe and adjacent parts of western Asia and northern Africa belonged to the same race. On this basis, he dropped the “European” race label and replaced it with “Caucasian.” Although he continued to distinguish American Indians as a separate race, he regrouped dark-skinned Africans as “Ethiopian” and split those Asians not considered Caucasian into two separate races: “Mongolian” (referring to most inhabitants of Asia, including China and Japan) and “Malay” (indigenous Australians, Pacific Islanders, and others).

Convinced that Caucasians were closest to the original ideal humans supposedly created in God’s image, Blumen-bach ranked them as superior. The other races, he argued, were the result of “degeneration”; by moving away from their place of origin and adapting to different environments and climates, they had degenerated physically and morally into what many Europeans came to think of as inferior races.214

We now clearly recognize the factual errors and ethnocentric prejudices embedded in Blumenbach’s work, as well as others, with respect to the concept of race. Especially disastrous is the notion of superior and inferior races, as this has been used to justify brutalities ranging from repression to slavery to mass murder to genocide.

It has also been employed to rationalize cruel mockery, as painfully illustrated in the tragic story of Ota Benga, an African Pygmy man who in the early 1900s was caged in a New York zoo with an orangutan.

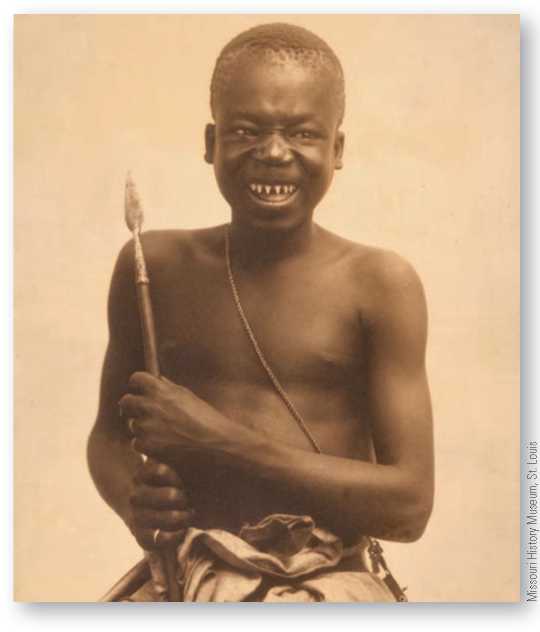

Captured in a raid in Congo, Ota Benga came into the possession of a North American businessman, Samuel Verner, looking for exotic “savages” for exhibition in the United States. In 1904, Ota and a group of fellow Pygmies were shipped across the Atlantic and exhibited at the World’s Fair in Saint Louis, Missouri. About 23 years old at the time, Ota was 4 feet 11 inches (150 centimeters) in height and weighed 103 pounds (47 kilograms). Throngs of visitors came to see displays of dozens of indigenous peoples from around the globe, shown in their traditional dress and living in replica villages doing their customary activities. The fair was a success for the organizers, and all the Pygmies survived to be shipped back to their homeland. Verner also returned to Congo and with Ota’s help collected artifacts to be sold to the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.

In the summer of 1906, Ota came back to the United States with Verner, who soon went bankrupt and lost his entire collection. Left stranded in the big city, Ota was placed in the care of the museum and then taken to the Bronx Zoo and exhibited in the monkey house, with an orangutan as company. Ota’s sharpened teeth (a cultural practice among his own people) were seen as evidence of

The placement of Ota Benga on display in the Bronx Zoo illustrates the depths of the racism in the early 20th century. Here's Ota Benga posing for the camera when he was part of the “African Exhibit” at the St. Louis World's Fair.

Johann Blumenbach ordered humans into a hierarchical series with Caucasians (his own group) ranked the highest and created in God's image. He suggested that the variation seen in other races was a result of “degeneration” or movement away from this ideal type. (The five types he identified from left to right are: Mongolian, American Indian, Caucasian, Malay, and Ethiopian.) This view is both racist and an oversimplification of the way that human variation is expressed in the skeleton. While people from one part of the world might be more likely to possess a particular nuance of skull shape, within every population there is significant variation. Humans do not exist as discrete types.

His supposedly cannibal nature. After intensive protest, zoo officials released Ota from his cage and during the day let him roam free in the park, where he was often harassed by teasing visitors. Ota (usually referred to as a “boy”) was then turned over to an orphanage for African American children. In 1916, upon hearing that he would never return to his homeland, he took a revolver and shot himself through the heart.215

The racist display at the Bronx Zoo a century ago was by no means unique. Just the tip of the ethnocentric iceberg, it was the manifestation of a powerful ideology in which one small part of humanity sought to demonstrate and justify its claims of biological and cultural superiority. This had particular resonance in North America, where people of European descent colonized lands originally inhabited by Native Americans and then went on to exploit African slaves and Asians imported as a source of cheap labor. Indeed, such claims, based on false notions of race, have resulted in the oppression and genocide of millions of humans because of the color of their skin or the shape of their skull.

Fortunately, by the early 20th century, some scholars began to challenge the concept of racial hierarchies. Among the strongest critics was Franz Boas (1858-1942), a Jewish scientist who immigrated to the United States because of rising anti-Semitism in his German homeland and who became a founder of North America’s four-field anthropology. As president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, Boas criticized false claims of racial superiority in an important speech titled “Race and Progress,” published in the prestigious journal Science in 1909. Boas’s scholarship in both cultural and biological anthropology contributed to the depth of his critique.

Ashley Montagu (1905-1999), a student of Boas and one of the best-known anthropologists of his time, devoted much of his career to combating scientific racism. Born Israel Ehrenberg to a working-class Jewish family in England, he also felt the sting of anti-Semitism. After changing his name in the 1920s, he immigrated to the United States, where he went on to fight racism in his writing and in academic and public lectures. Of all his works, none is more important than his book Mans Most Dangerous Myth: The Fallacy of Race. Published in 1942, it debunked the concept of clearly bounded races as a “social myth.” The book has since gone through many editions, the last in 2008. Montagu’s once controversial ideas have now become mainstream, and his text remains one of the most comprehensive treatments of its subject. (For a contemporary approach to human biological variation, see this chapter’s Anthropologist of Note.)

Generalized references to human types such as “Asiatic” or “Mongoloid,” “European” or “Caucasoid,” and “African”

Fatimah Jackson

While at first glance Fatimah Jackson's research areas seem quite diverse, they are unified by consistent representation of African American perspectives in biological anthropological research.

With a keen awareness of how culture determines the content of scientific questions, Jackson chooses hers carefully. One of her earliest areas of research concerned the use of common African plants as foods and medicines. She has examined the co-evolution of plants and humans and the ways plant compounds serve to attract and repel humans at various stages of ripeness. Through laboratory and field research, she has documented that cassava, a New World root crop providing the major source of dietary energy for over 500 million people, also guards against malaria. This crop has become a major food throughout Africa in areas where malaria is common.

Jackson, who received her PhD from Cornell in 1981, is also the genetics group leader for the African Burial Ground Project (mentioned in Chapter 1). In a small area uncovered during a New York City construction project, scientists found the remains of thousands of Africans and people of African descent. Jackson is recovering DNA from skeletal remains and attempting to match the dead with specific regions of Africa through the analysis of genetic markers in living African people.

Jackson, one of the early advocates for appropriate ethical treatment of minorities in the human genome project, is concerned with ensuring that the genetic work for the African Burial Ground Project is conducted with sensitivity to African people. She is therefore working to establish genetic laboratories and repositories in Africa. For Jackson, these laboratories are symbolic of the fact of human commonality and that all humans today have roots in Africa. As Director of the Institute of African American Research at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, Jackson continues with her own research while connecting and advancing scholars from diverse academic disciplines.

Or “Negroid” were at best mere statistical abstractions about populations in which certain physical features appeared in higher frequencies than in other populations; no example of “pure” racial types could be found. These categories turned out to be neither definitive nor particularly helpful. The visible traits were generally found to occur not in abrupt shifts from population to population but in a continuum that changed gradually, with few sharp breaks. To compound the problem, one trait might change gradually over a north-south gradient, whereas another might show a similar change from east to west. Human skin color, for instance, becomes progressively darker as one moves from northern Europe to Central Africa, whereas blood type B becomes progressively more common as one moves from western to eastern Europe.

Finally, there are many variations within each group, and those within groups are often greater than those between groups. In Africa, the light-brown skin color of someone from the Kalahari Desert might more closely resemble that of a person from Southeast Asia than the darkly pigmented person from southern Sudan who is supposed to be of the same race.

World History

World History