Dog (Canis)

The oldest domestic animal is the dog. Its wild ancestor is the wolf, Canis lupus. (The scientific nomenclature of domestic animals is not regulated by the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature. The system applied in this article is based on Uerpmann (1993).) There are indications for increasing approaches between humans and wolves at Upper Paleolithic sites in Central Europe. For instance, wolf bones are quite frequently found at mammoth hunter’s sites in Moravia. While hunting and killing animals does not appear to be an approach leading into domestication, it has to be assumed that hunting the adults would often have led to catching the very young ones alive. Wolf puppies are wonderful pets. As said before, raising young animals probably was the basic cause of animal domestication. However, domestication must not be seen as the inevitable outcome of this activity. At first, the raising of young ones only creates tame animals - animals that know how to behave in human society. Domestication may follow, but only if the adaptations to coexistence with humans are inherited to further generations.

In the case of the assumed tame wolves of the Upper Paleolithic, reproductive isolation from the wild wolves does not seem to have been complete. Differences between tame and wild individuals, caused by human preferences for particular properties of the ‘pre-dogs’, will have accumulated but slowly. Therefore, it remains difficult to detect these differences in the fossil record consisting of scattered bone finds. Good osteological evidence for dogs is not available before the Mesolithic. On the animal side, this must have been due to increased genetic isolation between tame and wild wolves - an isolation which had to be due to changes in the relation between humans and early dogs. We may speculate that increased importance of tame wolfs or ‘pre-dogs’ for finding game in a more vegetated landscape was a reason for paying more attention to these hunting companions. There is evidence for early dogs from Britain, Denmark, and other parts of Europe, and from the Near East as well, where we also find indications for an affective relation between humans and early dogs. Skeletal remains of young wolves or dogs are sometimes found in human graves.

Particular evidence for the process of domestication is also stored in the genetic code of animals. Comparative analysis of the DNA sequences of dogs and wolves yielded the most important information that - contrary to former assumptions - the North American wolves were not domesticated. PreColumbian dogs in America derive from animals which came from Asia together with the human population. Whether all dogs derive from East Asia, as also suggested from DNA evidence, remains questionable. The assumption that dog domestication should have happened in an area where the local wolves had a gene pool broad enough to contain most of the basic genetic variation of dogs would be plausible only if domestication was a natural evolutionary process. However, the primary cause for the approach between wolves and humans was the interspecific social capabilities of the latter. How would these people have been capable to realize which wolf population had enough genetic variability to encompass more than 95% of the respective variability of modern dogs? A polycentric or widespread origin of dogs throughout the former mammoth steppes of Eurasia would also be compatible with the DNA patterns of modern dogs (see DNA: Ancient; Modern, and Archaeology.

From the fossil record, it is difficult to reconstruct what the very early dogs looked like. They were smaller than wolves, but may not have looked very different. The manifold differences between recent dogs and wolves will have evolved after this initial phase when it became important for dogs not to be mistaken for a wolf. Wolves became enemies when humans started to have other domestic animals than dogs. Domestic sheep and goats are easy prey for wolves, but humans were not willing to share this base of their subsistence with the wolf.

Sheep (Ovfs) and Goats (Capra)

Sheep and goats were the next animals to become domesticated after the dog. Again, a lot of speculation is necessary to imagine a probable scenario for this process. The usual answer is that - for whatever reason - people at a certain point of their development needed additional or more secure sources of animal protein and that they therefore started to domesticate meat-producing animals. This answer is insufficient, however. Early hunters and gatherers experienced food shortages all the time, and - apart from the meat-‘eating’ dog - did not domesticate any meat-‘producing’ animals. The subsistence of the Magdalenian culture in western Europe, which flourished during the Late Pleistocene and created marvelous works of art found in the caves of southern France and northern Spain, was mainly based on hunting wild reindeer and horses. These large herbivores populated the open landscapes created by the cold and dry climate of the final Ice Age. The spread of forests at the transition to the Holocene dislodged these animals to the north and east. Severe shortages must have resulted for the Magdalenian hunters. They did, however, not react by domesticating reindeer or horse, although both species can be domesticated, as was proved much later when other conditions led to their incorporation into the human sphere. Looking at the long history of hunting and gathering as subsistence strategy, periodic shortages must have occurred many times and under many different sets of environmental conditions.

Actually, the conditions which lead to the domestication of sheep and goats were unique and very special. The same changes of global climate, which brought an end to the Magdalenian base of subsistence, favored the expansion of grasslands in the part of the Near East which is called the Fertile Crescent. These changes were not only favorable for the grasseating animals of that area, which in turn could be used by human hunters, but also yielded direct profit for the humans, because among the grasses of that area were the wild cereals. Rich stands of wild barley, rye, and wheat provided enough corn not only for the harvest season, but also for storage through larger parts of the year. These provisions lead to increased sedentism, including the origin of villages and even larger agglomerations of more or less permanent houses. The house - being part of the domestication concept - came into existence.

While the cereal harvest provided a carbohydrate base for human nutrition, animal protein still had to be obtained by hunting. The whole fauna of the area was exploited by the sedentary harvesters. Animal bones found in their settlements range from the large aurochs to turtles, fish, and even snails. The fact that even minor sources of protein were exploited is an indication that sedentism is not really compatible with efficient hunting. In particular, the larger and more fugitive prey would soon avoid the vicinity of permanent settlements. Nevertheless, these communities would also have brought back very young animals to the settlements when their mothers had been taken during a hunt. Actually, structured villages are much better for bringing up orphaned animal babies than ephemeral camps of hunters and gatherers. Particularly in the more mountainous and therefore more ecologically diverse areas of the Fertile Crescent, the Protoneolithic villages of the ‘hunting harvesters’ probably will soon have housed a veritable zoo of tame young animals. While growing older, their fate will have depended on their compatibility with humans.

It should be reminded that young animals reared by hunters and gatherers are generally not considered as economic resources. Depending on their specific patterns of behavior, adolescent animals might leave their foster communities on their own - probably soon falling prey to carnivores or hunters of other communities due to a lack of knowledge about living in the wild. The more social ones might try to stay, but human tolerance for an adolescent aurochs or stag would have been limited. Thus the duration of time during which reared animals could stay with their foster communities depended on factors like size, aggressiveness, required food, etc. Among the animals taken by the hunting harvesters of the Fertile Crescent, sheep and goats are the ones which had the potential to stay long enough with their human foster communities to reach sexual maturity and to actually breed in this sort of deliberate captivity. The conscious observation of spontaneous breeding and proliferation of these herd animals within human communities must have been the trigger for the Neolithic revolution of human subsistence.

While the above considerations only highlight the preconditions on the animal side of the domestication process, it is obvious that more or less conscious - but in any case complex - processes on the human side had to accompany the incorporation of beloved household animals into a revolutionary new subsistence strategy. A prolonged period of several generations of coexistence with tamed animals, where compunction hampered slaughtering and conscious exploitation, may have been necessary for these processes to develop. However, once the potential of controlled breeding of animals for meat production was recognized, a whole set of new social possibilities and necessities had to be managed and adopted on top of the changes brought about by the prior adaptation to harvesting and incipient cereal cultivation. It is obvious, however, that a unique coincidence of particular biogeographical factors and climatic conditions was necessary to trigger these adaptations. Apart from the Fertile Crescent, similar situations seem to have existed at the Pleistocene/Holocene transition in parts of Southeast Asia and in Central America. There, however, the final step of animal domestication was less successful due to the local lack of suitable middle-sized animals. While in Southeast Asia the domestic pig became a provider of meat on the level of small communities, the little animals like guinea pigs and turkeys first domesticated in Central America and northern South America could only reach this position on a family level.

Cattle (Bos) and Pig (Sus)

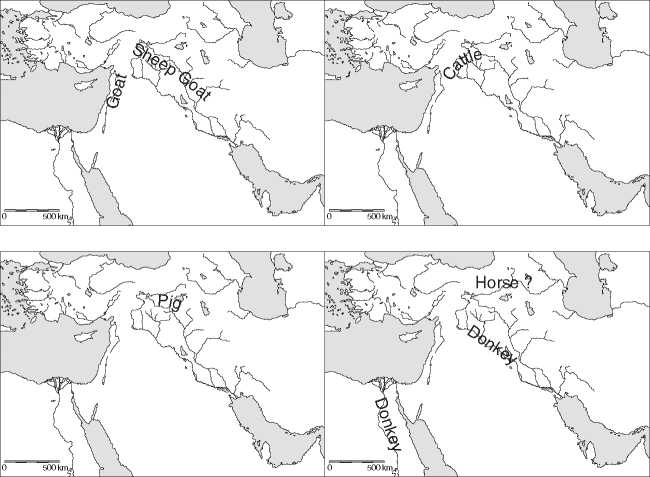

In the Near East, the incorporation of domestic sheep and goats into human subsistence economies was soon followed by the domestication of cattle and pigs. However, little is known about the actual processes leading to the addition of these animals to the livestock. One may assume that having domestic sheep and goats created the intellectual space for consciously adding other animals to the existing herds. Where this happened first within the Fertile Crescent is still unknown. The best available evidence for early pig and cattle domestication at present comes from the vertex of the crescent in the river systems of Euphrates and Tigris (Figure 2). When the Neolithic economy started to spread into Europe, a complete set of domestic animals consisting of cattle, pig, sheep, and goat provided a highly adaptable base of meat production, which could easily be adjusted to different local conditions and which provided the best possible insurance against catastrophic events, which rarely affect the different species to the same extent. It is interesting to read from the genetic evidence carried along by European livestock, that the European aurochs was not domesticated by the Neolithic farmers. Mitochondrial DNA, which is exclusively carried along the maternal line of inheritance, reflects a Near Eastern origin of European domestic cattle. A separate domestication is suggested for African cattle, and well documented for the humped or zebu cattle in South Asia.

For modern domestic pigs, there is genetic evidence for multiple domestications. It seems that the basic Neolithic stock of pigs in Europe was later replaced by locally domesticated animals. In South and East Asia, early pig domestications may have contributed to the independent development of food-producing economies.

Figure 2 Assumed centers of domestication.

Donkey (Asinus) and Horse (Caballus)

Based on cattle, swine, sheep, and goats, the subsistence economy of the Neolithic period flourished in Europe, the Near and Middle East, and North Africa for several thousand years without other animals being added to the stock. In Europe, it is the appearance of the horse which marks the first important addition. This is different in southwest Asia and northeast Africa, because there the donkey initiated the expansion of the domestic squad. Apart from donkey and horse, these additions later also included the Bactrian camel and the dromedary. All these additional animals were mainly used as beasts of burden and for riding.

The domestication of the donkey is still poorly understood. The wild ass, Equus africanus, occurred in arid to semi-arid regions throughout northern Africa from Somalia in the east to the coast of the Atlantic in the west, but also on the Arabian Peninsula including the dry parts of the Levant and Mesopotamia up to the foothills of the Taurus and Zagros Mountains. For a long time, palaeozoologists were not aware of the Asiatic part of the range of the wild ass, because its fossil remains were confounded with those of the so-called Asiatic wild ass, Equus hemionus. Therefore, the older literature considers Egypt as the only center of donkey domestication, and the donkey is sometimes seen as the only African species among the domestic mammals. However, up to now, the earliest finds of donkey bones are from the famous site of Uruk in Mesopotamia, where they are dated to the last quarter of the fourth millennium BC. This indicates that Mesopotamia was one center of domestication of this species. The other one certainly was in the Nile valley (Figure 2), where ancient Egyptian sources also illustrate how donkey domestication might have taken place.

Ancient Egyptian art gives insight into many aspects of the natural environment. Animals are quite prominent in all sorts of illustrations and the accuracy of animal depictions is most impressive. It is often possible to identify particular species of wild birds or fish from the pictures, and it is therefore not astounding that various wild mammals can easily be recognized. From such sources we know that the ancient Egyptians kept asses, ibex, Oryx antelopes, various gazelles, and other wild species in captivity. As these depictions usually belong to particular social contexts, it may be assumed that these motifs represent activities of outstanding members of the society. From Mesopotamia, there is evidence for special gardens where wild animals were kept. What can be inferred from depictions in Egypt and from texts in Mesopotamia might well be interpreted as a reaction to the alienation from nature at a time when villages started to become towns or even cities. Whatever the reason was to have captive wild animals at that time, it will in any case have had the potential to add new animals to the domestic stock, because breeding animals in captivity must inevitably always have been the first step toward their domestication (see above). However, with regard to domestication of the donkey, the last word has probably not yet been written.

It seems most likely that the horse was domesticated after the example of the donkey. Wild horses did not exist in the centers of early civilization where the donkey was domesticated. Their natural adaptation to the continental steppes of the Northern Hemisphere gave them a huge range during the cold phases of the Pleistocene, reaching from the Iberian Peninsula through Central Europe to Russia and Siberia and even across the then existing Bering Land Bridge over to Alaska and farther into North America. The spread of forests in the Post Pleistocene confined the wild horses to areas which retained an open, grass-dominated vegetation. The extent of such areas varied quite a lot during the Holocene, and therefore it is still difficult to determine exactly where wild horses would have been available for domestication. Obviously, there is a core area of steppes from Eastern Europe into Central Asia where wild horses always lived until they were exterminated in recent historic times. But in addition to that, more or less isolated populations existed on the Iberian Peninsula, temporarily in France and Central Europe, but during cool and dry climatic phases also in the Danube Plains and in the highlands from Central Anatolia to Armenia and northwestern Iran (Figure 2). If the assumption is correct that the donkey was the example for the domestication of the horse, the area mentioned last is crucial for the beginning of this process. However, actual research has been very limited until recently. There is evidence for the presence of domestic horses in Armenia at the beginning of the last quarter of the third millennium BC (unpublished results of recent research by the author). It is still not known, however, whether these animals were domesticated locally or imported from an earlier center of horse domestication elsewhere. In any case, the domestic horse made its appearance in ancient Mesopotamia at the very beginning of written history at the shift from the third to the second millennium BC. In Central Europe, it arrived during the second millennium BC, while on the Iberian Peninsula an independent domestication may have happened before. These views are in contrast to the older assumption that the horse was domesticated in the east European steppes during the fourth millennium BC. However, the evidence for this assumption is now widely considered as insufficient.

The Camelids: Bactrian Camel (Bactrianus), Dromedary (Dromedarius), Llama (Lama), and Alpaca (Alpaca)

The Bactrian or two-humped camel is the most enigmatic domestic species with regard to its early history.

Assumptions about the beginnings of its close connection to humans reach back into the Neolithic period, but there is no real evidence available. Its wild ancestor, Camelus ferus, is still found in remote parts of the Central Asian deserts, but was formerly more widespread, reaching west to the shores of the Caspian Sea and into Iran. One of its earliest appearances as a domestic or at least tame animal is documented by a Mesopotamian seal-cutter, who carved a schematic animal with a curved neck and two cylinders on its back into a seal sometime before the middle of the second millennium BC. Two persons are sitting face to face on the two cylinders on the back of the animal, indicating that the animal, which the seal-cutter apparently had not seen himself, could be ridden. There are other indications in the glyptic tradition of southwest Central Asia and Iran which indicate that the Bactrian camel may have been domesticated in that part of the world, perhaps as early as the third millennium BC. For the time being, however, no biological evidence is available for this process.

The dromedary or one-humped camel is slightly better known than the Bactrian camel. It appears in the historical record and art of the Near East toward the end of the second millennium BC. From the same time onward, its bone remains become more and more common among the faunal remains studied from the same area. The problem about this species for a long time was its wild ancestor. There are no wild dromedaries today. Assumptions went as far as to believe that the one-humped dromedary was but a domestic variant of the Asiatic two-humped camel. However, the lack of evidence for wild dromedaries is only due to the bad conditions for fossil bone preservation in the Arabian deserts, which were the ecological niche, to where wild dromedaries retreated during the final Pleistocene. In the Pleistocene, they occurred in a very large form (Camelus thomasi) not only in southwest Asia but also in North Africa. As a real desert animal, the wild dromedary lost a large part of its former habitat, when climatic conditions became moister toward the Holocene. Therefore, the better-explored areas of North Africa and the Near and Middle East, which are also the areas preferred by the human inhabitants, became void of wild dromedaries. With progressing archaeological research in some parts of Arabia, this gap in our knowledge has started to close.

Apparently, the dromedary was the latest addition among the large mammals to the domestic stock. The historical, pictorial, and morphological evidence indicate domestication toward the end of the second millennium BC. Why and how this happened is still a matter of speculation. Apart from the general fact

That this must have been on the Arabian Peninsula, the exact whereabouts are also still unknown. The morphological evidence, used as an example earlier (Figure 1), does not indicate a transitional period in the area of southeast Arabia from where the data come. Whether this indicates that domestic dromedaries arrived there fully domesticated, or whether their morphological changes happened too fast to be visible on the archaeological timescale, is not yet known.

The domestic South American camelids llama (Lama) and alpaca (Alpaca) were also quite enigmatic with regard to their domestication history for a long time. It seems fairly well established now that they originated from the two local wild species guanaco (Lama guanicoe) and vicufia (Vicugna vicugna), respectively. Their domestication may have started as early as the fourth millennium BC, but the circumstances of this process are not clear at all. The role of the camelids within the early prehistoric development of the human populations of the respective areas in the South American Andes is difficult to assess at a regional level. Changes observed at individual sites are difficult to interpret as long as it remains difficult to correlate them to the general environmental history of the area and to more widespread changes in human subsistence and settlement patterns. Nevertheless, the domestic South American camelids must have played an important role during the development of advanced civilizations in that part of the world.

The Cat (Catus) and Other Small (Semi-) Domesticated Carnivores

Among our domestic animals, the cat has remained the most independent creature till today. In particular, with regard to reproduction, human control over this species is not too efficient. This independence sheds some light on the process of domestication of this species as well. As young cats are very attractive pets, one may well assume that cat domestication started in the same way as the domestication of the dog. Rearing young wild cats would have created a tame population living within human settlements, but without genetic isolation from the wild population in the surroundings. Therefore morphological and other changes due to domestication would not have accumulated. This goes well with the observation that the many mummified cats found in old Egyptian contexts cannot really be distinguished from the North African wild cat, Felis silvestris libyca, although one may well assume that they lived tame among the humans. Transformation of the cat into a ‘real’ domestic animal will therefore have depended on the disappearance of the wild cats within the range of the tame ones. This would have happened when human settlements became towns or cities and thus too large for the tame cats to reach the surrounding wilderness where the wild tomcats would have waited for them. Another important factor may have been the introduction of domestic fowl in human settlements. As a wild cat would not have hesitated to consider a chicken as prey, the tolerance for these animals within settlements will have disappeared quickly after the domestic chicken arrived in the Middle and Near East, from where it spread farther to the Mediterranean and Europe (see below).

Taming of wild cats may have happened anywhere in the huge range of the wild cat. Cats will have been welcome in settlements because they act as control of rodent pests. Their domestication will, however, have depended on genetic isolation from the wild surroundings. Therefore the appearance of real domestic cats is fairly late in the archaeozoological record. For Europe, this is generally the time of the Roman Empire.

Another small carnivore, the mongoose Herpestes edwardsi, lives in South Asia in a semi-domestic condition till today. There is no control over its reproduction. Therefore the animal has not developed domestic characters, but can be considered as a candidate for real domestication as soon as contacts will be lost between the tame and the wild population.

The ferret is a domestic polecat (Mustela putorius), and has passed the line between tame and domesticated, because it displays obvious differences from the polecat, like a whitish color, and also has skull characters which can be interpreted as domestication changes. Its domestication seems to have occurred during the Middle Ages. Other members of the mus-tellid family, like the mink, are among the very recent domesticates. They owe their status not so much to conscious domestication, but simply to the fact, that these species were bred in captivity for the production of pelts. Captivity - not tameness - achieved genetic isolation from the wild population in these cases. The isolation produced changes in coloration which are sufficient to consider these animals as domestic, because they live under human control and they are different from their wild relatives.

Domestic Fowl: Chicken (Gallus) and Other Small Domestic Animals

The wild ancestor of domestic chicken, the Bankiva hen (Gallus gallus), lives in South Asia from India to Vietnam and southern China. Its domestication must have started in that area and is not yet really known. It must have spread from India to the west during the second millennium BC, because there is a historical document from the time of Tuthmosis III in Egypt, which mentions ‘‘the bird which lays an egg every day.’’ It is unknown how the domestic chicken reached Egypt so early, because the known harbor sites on the shores of the Arabian Peninsula have not yielded chicken bones among the faunal remains from the second millennium, although maritime contacts to the Indus civilization are indicated there in large style by all sorts of transported goods.

Early in the first millennium BC, chicken spread from the eastern coasts of the Mediterranean to the Aegean and as far west as southern Spain. In Central Europe, it appears as indication of Mediterranean contacts during the final phase of the Hallstatt civilization soon after 500 BC. Obviously, it filled a niche at that time of transformation from rural to township life. As small animals, which can make their living on what remains as offal from the human table, chicken could even be kept in cities.

Another small animal which could give a city dweller the feeling that he was in charge of some food production himself is the domestic rabbit (CuNi-CULUS). This is clearly a European addition to the domestic stock, because its wild ancestor, Oryctola-gus cuniculus, occurred only in the southern and eastern coastland of the Iberian Peninsula and in southern France. Among the small wild animals kept in Roman times in so-called leporaria, it was the only one that started reproduction in captivity. Breeding under human control in isolation from the wild population was again the starting point of domestication. Like few other animals, the rabbit took enormous advantage from its close companionship with humans, because with human help it could spread its range almost worldwide.

To keep animals for momentary reasons - not with the aim of transforming them into something that could not be foreseen. Those animals which were able to reproduce under the man-made conditions became domesticated. Others, which did not, have remained ‘wild’, because reproduction in isolation is the most important precondition of domestication.

This is also the case for the largest animal, which lives close to humans: the Indian elephant is the best example, that tameness is not domestication. There are no domestic elephants, because breeding these animals in captivity is difficult. It is also not ‘necessary’ in the case of the elephant, because the tame females are easy to handle, have a long life expectancy, and up to now could easily be replaced by taming a new young wild elephant. It will be interesting to observe, if someone will have the idea to really domesticate the Indian elephant, when it becomes more and more difficult to find reproducing wild herds.

The observation of modern domestications is an important reason for being sceptical about intentional domestications in the past. Favorable conditions of human life are a plausible reason for changing relations with particular animals in terms of keeping them alive for some time instead of eating them immediately. On the other hand, food shortages and the dubious human capacity to foresee what will be needed in the future - together with the fact that the economic success of domestication could not be predicted - are unlikely to have stimulated a process which in any case took too long to produce an immediate response for the individual who started it.

See also: DNA: Ancient; Modern, and Archaeology; Plant Domestication; Hunter-Gatherers, Ancient.

Recent Domestications

Since the beginnings of city life in the Near East and the wider Mediterranean, more small animals like the carp, doves, ducks and geese, and also the bee and the silk worm have entered the human sphere and more domestications are going on today. Quite a number of species have become domesticated under the eyes of modern science, but this is rarely verbalized. There is no doubt that the guppy fish and many other species which populate the fish tanks of the civilized world are now domestic animals. The same is true for budgerigars, canaries, and some other popular species of birds, and also for some small mammals, which have developed forms under human control, which do not occur in the wild. None of these domestications were planned.

World History

World History