The Australian rainforests are thought to be one of the last environments to be colonized by Australian Aborigines, with permanent settlement of this environmental zone not occurring until the last few thousand years. Pollen cores from the northeast of the continent have been interpreted, from microscopic charcoal patterns and shifts in forest types, as evidence of a human presence in these areas over 40 000 years ago. However, the archeological evidence has not been forthcoming to support rainforest occupation in any intensive way until 2 ka. The archaeological site of Jiyer Cave, located on the Russell River on the Atherton Tablelands southwest of Cairns, provided the first indication of antiquity of rainforest occupation when basal ages of c. 5000 BP were obtained, and until recently it was the earliest evidence of rainforest occupation in Australia. Recent work in the Wet Tropics World Heritage Area on the Tully River to the south of this area (Figure 1) has now extended this occupation to c. 8000 cal BP at the site of Urumbal Pocket (Figure 11). However, occupation rates prior to 2 ka are indicative of ephemeral use of this landscape and it was not until c. 1.8 ka that permanent occupation of the rainforest is established. Excavations here have yielded evidence of a sustained increase in toxic nut exploitation, particularly Beilschmiedia bancroftii, the yellow walnut, from around 2.5 ka climaxing at c. 1.5 ka. The pattern of

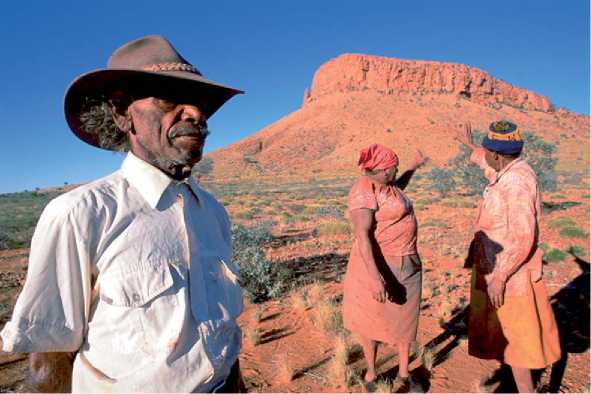

Figure 9 Puritjarra Rockshelter, Central Australia, November 1986. Photograph © M. A. Smith.

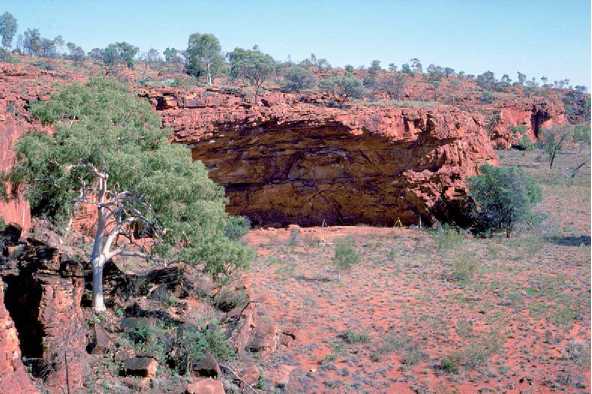

Figure 10 The Karrku ochre mine near Puritjarra Rockshelter in Central Australia. Photograph © Tim Wimbourne.

Figure 11 Excavations underway at Urumbal Pocket located in the wet tropics region of northeastern Australia. The site is adjacent to the Tully River channel which was dammed 50years ago for hydroelectricity. The basal occupation dates of c. 8ka make it the oldest known rainforest occupation on the Australian continent. Photograph © Judith Field.

Toxic nut use lags just behind artifact discard rates at each site investigated in the study. At least for Australia, it would appear that like the arid zone, the development of technologies that provide access to particular plant food resources may be the limiting factor in permanent occupation of these environments.

World History

World History