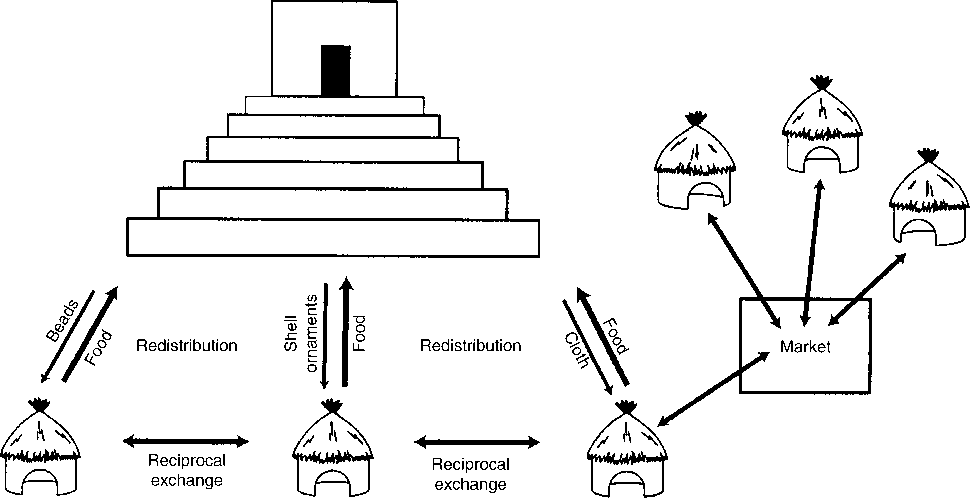

In archaeology, systematic and concerted efforts to theorize and reconstruct past patterns of exchange and distribution began during the second half of the twentieth century. Research on this central aspect of past and present economies was prompted by the seminal writings of Karl Polanyi and Marshall Sahlins, who described basic modes of circulation (reciprocity, redistribution, and marketing), which then were closely linked to different organizational formations by Service, Fried, and others (Figure 1). At the same time, concern with defining the principal factors that prompted key societal evolutionary transitions led archaeologists to pose research questions that endeavored to assess the relative importance of local versus long-distance exchange (as well as other postulated ‘prime movers’ such as warfare, demographic growth/pressure, and irrigation) in specific historical contexts. With the advent of these theoretical queries, archaeologists no longer found it sufficient or even adequate merely to categorize the external contacts between social groupings as either migration or diffusion, thereby focusing greater attention on the broad range of behaviors, many with economic implications, that could transmit various goods and information across space and between societies.

In his highly influential works that structured decades of later conceptualization and research in archaeology, Polanyi outlined an association between the economic predominance of reciprocal exchanges (face-to-face transactions between known or symmetrically situated individuals) with small, egalitarian sociopolitical formations. At the same time, redistribution, a circulatory mode in which goods flowed into a central settlement or nodal power broker and then back out, was seen as almost a definitional aspect of chiefdoms and their economic underpinnings. Market exchange was thought to be important only in a select subset of later states and largely was associated with capitalism.

Although these early views still have some validity and support, past modes of circulation and economic interaction have been shown by decades of

Figure 1 Modes of exchange.

Archaeological investigation and analysis to be far more complex and variable than Polanyi’s scheme envisioned. In particular, the importance and broad relevance of redistribution has been called into question in many global contexts, and, generally, archaeologists have found far less evidence of direct political controls over production and exchange than may have been thought 25 years ago. To begin with, if much craft production was situated in houses, such manufacture would be difficult for political authorities to monitor or control directly. Nevertheless, there are other ways for governing officials to tap the sources of production through mechanisms like tribute.

More specifically, archaeological research has shown that bulk commodities, like grain, often are moved through different networks and mechanisms than were employed for rare, highly valued goods, such as metals, jade and gemstones, and marine shell. In certain regions of the world, a third class of items of intermediate worth has been defined, including obsidian (volcanic glass) and woven cloth. Items in this class exchanged through channels that neither conform to the prestige good exchanges of high valuables nor to the paths traveled by basic staples. These complexities now make it difficult to characterize the breadth of ancient economies into a small number of discrete modes or to distinguish them from modern economic systems in some kind of categorical or rigid manner. For example, market exchange has been shown to have had a greater role in the circulation of goods in precapitalist contexts (including Mesoamerica, China, Greece, and Rome) than would have been supposed in Polanyi’s era.

Archaeologists have devised and adopted a series of analytical means to assess the movement of goods, and hence the channels and mechanisms through which exchange took place in specific settings. Traditionally, the form and stylistic aspects of specific artifacts have been used as visual clues to trace patterns of interaction. Yet artifact forms can be copied, or even appear similar by chance. So it is not always safe to use resemblance alone to distinguish an imported piece in a given archaeological context from something locally made. Much more secure inferences regarding exchange can be drawn if it can be demonstrated that an artifact was made in a locale other than where it was found. Characterization refers to a bevy of techniques of examination by which key properties of the constituent materials are identified, thereby allowing the source of that material to be determined.

If characterization is to be effective, there must be certain attributes that distinguish the products of one source of certain materials from others. Generally, this cannot be achieved by visual means alone, and it is necessary to employ chemical, petrological, or physical means to distinguish the materials from different sources. Some of the first characterization research was carried out with obsidian, which was valued in many past societies, since it can be knapped to create sharp chipped stone cutting edges. The main elements (including silica, oxygen, and calcium) of which obsidian is composed are largely the same the world over, but the rare additional elements are markedly different from one source to another. Since distinct obsidian quarries can be distinguished by the specific composition or signature of these rare trace elements, a number of different chemical techniques (including neutron activation and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry) have been employed over the years to identify the sources of this material. Given the widespread use of obsidian, such characterization studies have yielded important findings on exchange patterns for the Mediterranean, the Pacific, and across much of the Western Hemisphere.

Since the possible sources of clay and most kinds of stone other than obsidian are numerous and diverse, there is much less chance that similar chemical analyses (reliant on a small number of distinct elemental signatures) can be employed to source them with a degree of resolution comparable to that reached for obsidian. Alternatively, petrological methods that examine stone or ceramic materials by taking a thin section of the target material and placing it under a light microscope can yield information on the rock and mineral structure of such materials. For certain stone materials (particularly building stone), such findings have successfully matched artifacts to their quarry or source. Ceramic artifacts, which frequently are composed of clay and mineral, sand, or rock inclusions, also have been profitably studied through these petrological methods. Yet because the fabric or composition of ceramics often is made from materials derived from more than one source (the clay mine and the sand or mineral source), the challenge of characterization is generally greater than it is for stone. Nevertheless, petrological techniques (especially when employed quantitatively) can provide a mineral signature for sets of pottery objects made with a specific recipe, and therefore such procedures help define the paths by which these vessels were moved. If the petrological characterization of the mineral composition is supplemented by chemical analyses of the clays, then often even greater resolution can be gained. Physical techniques, such as X-ray diffraction, that define the crystalline structure of minerals based on the angle at which X-rays are deflected also have been employed for the characterization of pottery as well as certain stone materials.

Characterization studies (and other means of documenting the movement of goods from their source) permit archaeologists to define distributional patterns and hence some of the ways that communities and valuables circulated. When regional and even larger-scale perspectives on the archaeological record are available, quantitative spatial techniques have been employed to define these distributional patterns. One of the key questions that still needs to be adequately tackled by archaeologists concerns the scale of many past economies and economic relations and how these interactions shifted over time. Prior to the advent of systematic settlement pattern studies in many regions of the world, archaeologists tended to focus on small physiographic regions when examining exchange and economic interactions, presuming that important relations were almost entirely local in character perhaps due to the limits on transportation technologies. Yet in parts of the ancient world, high volumes of certain commodities and precious goods were indeed transferred over long distances in significant enough quantities to have clear systemically important economic effects on the polities involved.

World History

World History