Major issues in the archaeology of the Palaeolithic in Central Eurasia concern the entrance and adaptation of hominid groups in the region. Foremost is the

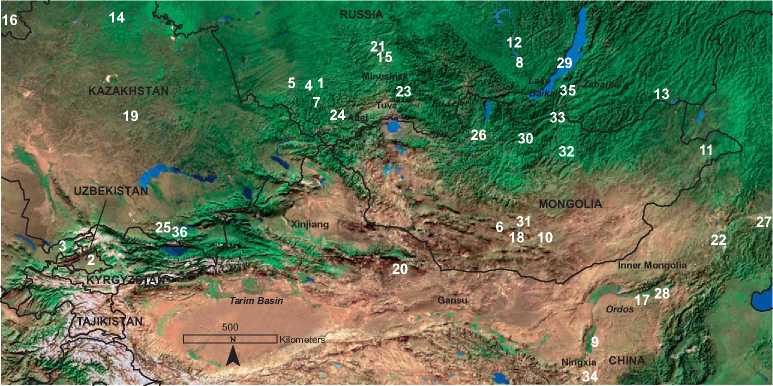

Figure 1 The geography and major archaeological sites of Inner Asia and peripheral regions, as numbered: (1) Ulalinka, (2) Teshik-Tash, (3) Obi-Rakhmat, (4) Denisova Cave, (5) Okladnikov Cave, (6) Tsagaan Agui, (7) Kara-Bom, (8) Mal’ta, (9) Shuidonggou, (10) Shabarak Us, (11) Tamsagbulag, (12) Ust’-Ida, (13) Budulan, (14) Botai, (15) Suchanicha, (16) Arkaim/Sintashta, (17) Zhukaigou, (18) Zuukh, (19) Atasu, (20) Qizilchoqa, (21) Karasuk cemetery, (22) Nanshangen, (23) Arzhan, (24) Pazyryk, (25) Issyk, (26) Uushigiin Ovor, (27) Xiaobaiyang, (28) Maoqinggou, (29) Khujir, (30) Egiin Gol/Burkhan Tolgoi, (31) Tebsh Uul, (32) Noyon Uul, (33) Tsaram, (34) Daodunzi, (35) Ivolga, (36) Tuzusai.

Problem of the initial peopling of the cold grassland environment of Central Eurasia. At what point did human ancestors first appear in the region, from where, and what technologies supported their existence in this novel setting? Having arrived, how did they adapt and interact, particularly as evidenced by the lithic technologies they left behind? These are basic questions that concern early human mobility and its development, a topic critical to the archaeology of Central Eurasia during all periods.

The Lower Palaeolithic

Discovery of early hominids at the site of Dmanisi (1.8 MYA) in the Caucuses and finds in Northeast Asia approaching 1 MYA has greatly strengthened the understanding and possible explanations of Lower Palaeolithic finds in Central Eurasia. With the exception of the skull fragment discovered at the site of Salkhit (northeastern Mongolia) in 2006 and now under intensive study, no other early homined fossils have yet been found in the steppe lands. However, the artifact sites of the earliest steppe inhabitants have been discovered, demonstrating that the range of early homi-nids expanded to include most of Eurasia. The artifact record is not without problems. Questions arise as to whether artifact assemblages claimed as evidence for Middle Pleistocene manufacture are not in fact the results of geological processes. In other cases, lithic assemblages may be indisputable, but were found from geological contexts which make their periodization uncertain. In south Tajikistan, Lower and Middle

Pleistocene pebble industries at the sites of Kuldara and Karatau represent the early evidence of hominid dispersals along the edges of Inner Asia. Early sites in Siberia at Ulalinka, Mokhovo I, and Diring Yuriakh have flaked stone assemblages thought to date prior to 300 000 years ago, however, whether these assemblages are actually human-made has been disputed. The current evidence for hominid entry into Siberia is younger than 200 000 years and is marked by Middle Palaeolithic technologies (see Siberia, Peopling of).

The Middle Palaeolithic

The Middle Palaeolithic archaeological record of Inner Asia is more detailed. It is part of a Eurasiawide technological and cultural sequence. Three major divisions of stone tool technology have been identified at Middle Palaeolithic sites: Mousterian forms, Levallois type technologies, and incipient large blade industries with connections to Upper Palaeolithic technologies. These technologies form a chronological separation among sites, and also demonstrate the relationship of Inner Asia Middle Palaeolithic technologies with those of Western Eurasia where the same broad sequence has long been known. Further links to Western Eurasia were the discovery in 1939 of a Neanderthal sub-adult skeleton at the cave site of Teshik-Tash and the 2003 excavation of sub-adult teeth and cranial fragments from the Obi-Rakhmat rockshelter, which may also be related to Neanderthal populations. Both sites are located on the western slopes of the Tian Shan Mountains of Uzbekistan.

Some of the most important Middle Palaeolithic sites of Inner Asia are those of the Anui River valley in the Altai Mountains. The principal Middle Palaeolithic sequence is found at the sites of Denisova Cave and Okladnikov Cave with the former providing the bulk of the record. The Denisova cave habitation dates back possibly as early as 130 000 years ago and covers the extent of the Middle Palaeolithic. Also recovered at Denisova Cave were teeth from a hominid identified as Neanderthal-like. This evidence and the skeletal finds from Teshik-Tash and Obi-Rakhmat, lend credence to the argument that much of this region was inhabited by hominids akin to the Neanderthals of Europe or other archaic human species, though this question is still controversial. Other cave sites such as Ust’ Kan, Kara-Bura, and Obi-Rakhmat, as well as open air scatters and flint quarries such as Kapchigai, located in the Altai and Tian Shan Mountains, testify to the effective adaptations of Middle Palaeolithic groups of the region.

Middle Palaeolithic artifacts are found on the eastern flanks of the Altai and Tian Shan Mountains as well, though no sites of the depth and scale of the western Altai sites are known. The recently excavated cave at Tsagaan Agui in central Mongolia and the Tolbaga site near Lake Baikal represent the Middle Palaeolithic technologies of central Inner Asia. The transition to new stone tool technologies of the Upper Palaeolithic occurred by 40 000 years ago. Many major sites, such as Tsagaan Agui, Obi-Rakhmat, and Okladnikov Cave, contain continuous sequences from Middle Palaeolithic to Upper Palaeolithic materials. There are also new transitional sites such as Kara-Bom, the earliest Upper Palaeolithic site yet discovered at 43 000 BP.

The Early Upper Palaeolithic

Upper Palaeolithic technology is based upon blade manufacture and prepared cores. Other finds include art objects and habitation structures. Typical Early Upper Palaeolithic sites are on terraces with good visibility overlooking the surrounding landscape. When these sites are large, they have hearths, pit features, and stone rings that supported structures. Smaller sites have unlined hearths and work areas, but few signs of long-term habitation. Cave sites continue to be used in this period, but are not the main focus of habitation. A number of cache sites, places where stone tools and raw materials were stored, have also been discovered. On the west Siberian plain, open-air sites with the remains of tundra and boreal megafauna including bison, reindeer, woolly rhinos, and mammoth are found, such as the mammoth-kill site at Tomsk. In Anui valley of the Altai Mountains, Okladnikov Cave continued to be used during this time and contains Early Upper Palaeolithic layers dated to 42 000-33 000 BP, while the open air site of Ust’ Karakol nearby dates to 31000BP.

In south central Siberia, Upper Palaeolithic sites date no earlier than 30 000 BP. The most famous of these sites is Mal’ta of the Angara river basin, which dates to 23 000 BP. A large area of this site has been excavated and tens of thousands of lithic and bone tools, and faunal remains were found along with organized habitation structures. The site is interpreted as a seasonal reindeer hunting camp that was used repeatedly. Other notable sites in the greater Baikal region include the stratified sites of Krasny Yar and the riverside bluff site of Kamenka in the Lower Selenge river valley. Farther afield, the cave site of Tsagaan Agui at the northern edge of the Gobi desert continued to be used. Shuidonggou, south of the Gobi and north of the Yellow River is the southernmost major site of the Inner Asian Upper Palaeolithic type.

There are scores of Upper Palaeolithic sites recorded from Inner Asia and based on their chronology and distribution, it is possible to observe how Pleistocene climate fluctuation and glacial cycles created variable biogeographic conditions that affected when and where human groups lived. Expanding glaciers and cold regions pushed people southward while retreating glaciers re-opened formerly inaccessible areas. The final iteration of this long-term process followed the conclusion of the last glacial maximum (18 000 BP) and brought populations back into Siberia by 14 000 BP, and across Beringia to North America.

The End of the Upper Palaeolithic

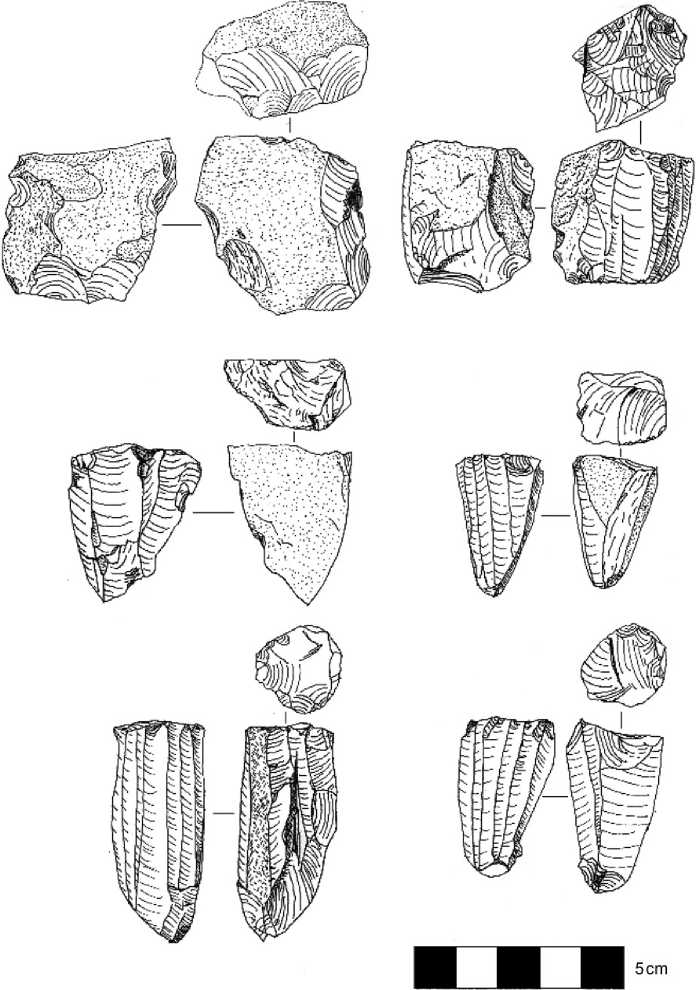

Following the last glacial maximum, the Holocene environment of Inner Asia stabilized close to the conditions we know today, initiating the terminal stage of the Palaeolithic. The final innovation in lithic technology across Inner Asia was the invention of microblade technology. Developing out of local Upper Palaeolithic traditions, this technology centered on interchangeable and easily replaceable lithic components in many types of compound tools. The material remains of microblade technology are distinctive core forms and very small bladelets (Figure 2). Also during the Holocene, site locations shifted to emphasize riverine valleys, river banks, and confluences. Site composition, the animals hunted, and artifact assemblages all suggest that these people were more mobile than their mid Upper Palaeolithic predecessors. Sites were inhabited for short periods and revisited repeatedly, rather than occupied for longer spans of time. Microlithic tool users began to inhabit high elevation regions such as the upper Altai and the Tibetan Plateau, and a notable fluorescence of habitation

Figure 2 Prismatic cores for the production of microblades, north central Mongolia.

Appeared around Lake Baikal in South Siberia and in the desert oases of the Tarim Basin, Xinjiang.

World History

World History

![Road to Huertgen Forest In Hell [Illustrated Edition]](https://www.worldhistory.biz/uploads/posts/2015-05/1432477693_1428700369_00344902_medium.jpeg)