Although the study of Greek colonization, colonies, and overseas settlements has a long history, there are some methodological issues to be addressed, not least the term ‘colonization’. There has been some discussion of the appropriateness of the term to the Ancient Greek context. Was what happened really colonization or just a form of migration? Nowadays, colonization is generally recognized as a modern Anglophone concept, based on imperial activity in the recent past, transported back and forced onto Ancient Greece; the usefulness of applying such terminology to the ancient world is debatable. In reality we are talking about words, and since ‘colonization’ has been in common currency, it is hard to abandon its use. The fact is that there were Greek settlements outside the Greek mainland.

We have few, if any, ancient written sources contemporary with Greek colonization. Our information comes from a whole range of Greek and Latin authors. Herodotus (c. 485-425 BC), Thucydides (c. 460/455-395 BC), Strabo (c. 64/3 BC-AD 23), Pseudo-Scymnus (c. 138-74 BC), and Eusebius (c. AD 260-339) are our main sources on the establishment and description of colonies. Although in the Odyssey Homer provides us not just with information on geography, trade, and life in the Greek city but with an account of an ideal colonial site, we do not know when Homer lived (the latest suggestion is the mid-seventh century BC). Ancient authors give foundation dates for colonies, for instance Thucydides those for Sicily. But how accurate are these dates when he was writing a few centuries later? The dates given in ancient written sources need to be compared with those obtained from archaeological evidence, especially the earliest Greek pottery found in colonial sites (see Table 1). Even this approach has drawbacks: how extensively

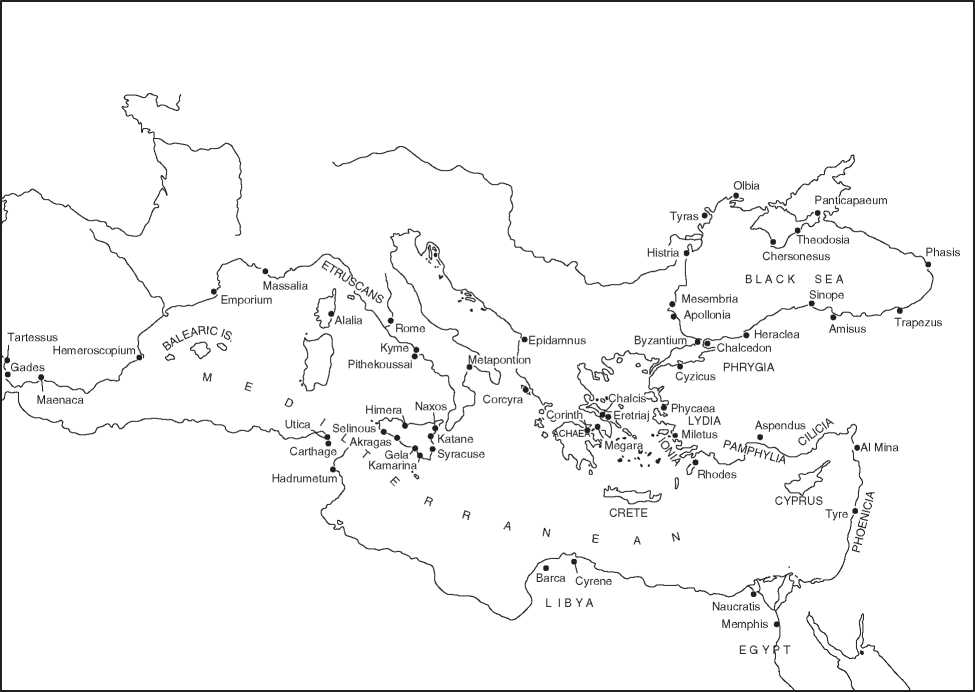

Figure 1 Major Greek colonies in the Mediterranean and Black Sea. Source of illustration: Tsetskhladze GR and De Angelis F (eds.) (1994) The Archaeology of Greek Colonisation. Oxford: Oxford University School of Archaeology, endpapers.

Adapted from Graham (1982), 160-162, Osborne (1996) 121-125, with additions from Tsetskhladze and De Angelis (1994) passim, and Hansen and Nielson (2004) passim.

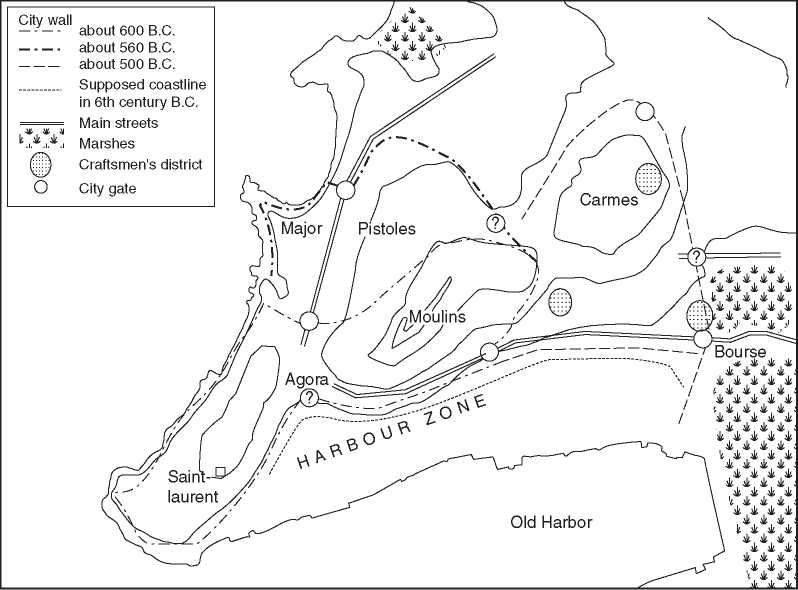

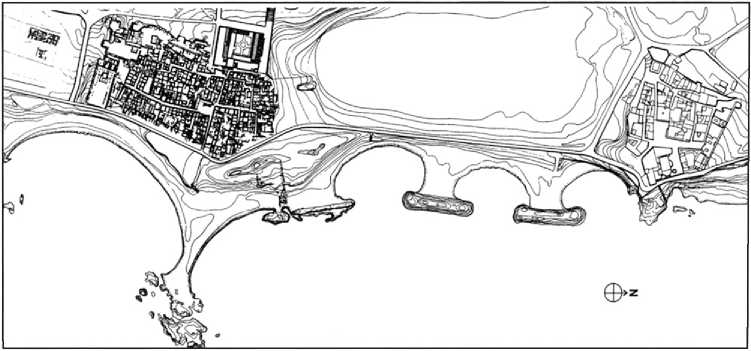

Has the site been studied and have the earliest habitation levels been reached? In several cases we know the name of a colony from written sources but have been unable to locate it archaeologically, or unable to investigate it since it lies under a modern city. The first Greek colonies and overseas settlements were small, situated mainly on peninsulas for easier defence. Since the Archaic period the landscape has changed - sea levels have risen, peninsulas have become islands, suffered erosion, been submerged, etc. (Figures 2 and 3).

We face pitfalls with the terminology used by ancient authors to describe Greek cities and colonies. It all comes from (and applies to) the Classical period and later. Its application by many modern scholars to the Archaic period complicates more than it clarifies. According to the ideal Classical concept of a polis (city-state), each city should have a grid-plan, fortification walls, a designated area for temples and cult Activity (temenos), market-place (agora), gymnasium, theater, etc. Indeed, we can identify these features more or less easily when excavating Classical and Hellenistic sites, but they were not the norm in earlier periods. Even to use the term polis for the Archaic period, either in mainland Greece or in the colonial world, causes problems: the concept belongs to a later

Date and describes a city-state enjoying independent political and social institutions (not least its own constitution), and furnished with an agricultural territory (chora). The term apoikia is generally used for colonies; its literal translation is ‘a settlement far from home, a colony’. Although the term carries no particular political or social meaning, it can include a proto-polis with independent political and social arrangements and a chora. To distinguish another kind of colonial settlement, emporion is used. It is a kind of trading-post or settlement, lacking a chora or any independent social and political structure, established in a foreign land, either as a self-contained site or as part of an existing native urban settlement, sometimes with the permission of local rulers and under their control. The first use of the term empor-ion was by Herodotus in the fifth century to describe lonian Naucratis in Egypt (see below). But this term too is artificial: a polis was also a trading center, sometimes with a designated area called, in ancient writings, an emporion. Excavation of so-called emporia demonstrates that these were not just trading stations but also centers of manufacture. In recent times the formulation port-of-trade (introduced for the first time for the ancient world by K. Polanyi in the 1950s-60s) has gained increased favor with

Figure 2 Plan of Archaic Massalia (now Marseilles, southern France). Initially, colonies were small, as the city walls of about 600 BC clearly demonstrate in this case; with the increase of population, a greater area was enclosed. The coastline has changed since ancient times: the ancient harbor is now dry land. Source: Tsetskhladze GR (ed.) (2006) Greek Colonisation. An Account of Greek Colonies and Other Settlements Overseas, vol. 1. Leiden: Brill, 363, fig. 3.

Figure 3 Topography of Emporion (Spain). The initial settlement was established on a small off-shore island called Palaiapolis (right of plan; now linked to the mainland). Later, the colony was moved to the mainland, called Neapolis (left of plan). Source: Tsetskhladze GR (ed.) (2006) Greek Colonisation. An Account of Greek Colonies and Other Settlements Overseas, vol. 1. Leiden: Brill, 475, fig. 26.

Historians of the ancient economy; for example, Archaic Naucratis is so labeled, although it was more than a trading place - it manufactured pottery and scarabs. Thus, once again, modern conceptions are applied to ancient reality.

The reasons for colonization are the most difficult to identify and disentangle. There were particular reasons for the establishment of each colony and it is practically impossible to make watertight generalizations. Many writers adopt a perspective influenced by modern experiences: overpopulation, food shortages, the hunt for raw materials, etc. Ancient written sources seldom mention reasons; where they do, the emphasis is always on forced emigration. The eighth century BC is not the seventeenth to eighteenth centuries AD. In the Archaic period there was little knowledge of distant lands; no trade routes plied regularly by shipping. According to one modern scholar, it was ‘murder’ to establish a colony. The people had no idea where they were going, how many of them would get there, and what they would find when they did. Another practice known from ancient times is of tyrants disposing of (to them) undesirable people by forcing them to migrate. The population of the earliest colonies was small; we have few definite figures, one is of 1000 people at Leucas, 200 at Apollonia in Illyria and the same number at Cyrene. The most obvious of example of forced migration in response to a clear set of circumstances is Ionia in East Greece, a very wealthy region in modern-day western Turkey with Miletus as its main city. From the second half of the seventh century, neighboring Lydia began to expand, gradually absorbing Ionian territory; this was the time that Ionia sent out its first colonies. Greater misfortune befell it from the middle of the sixth century when the Achaemenid empire began to conquer Ionian territory and then, in the wake of the Ionian revolt in 499-494 BC, laid it to waste. Ancient written sources indicate directly that the Ionian population fled from the Persians - their choice was flight or to remain and be enslaved or killed. Thus, they established between 75 and 90 colonies around the Black Sea and several in the western Mediterranean. Of course, there was a shortage of land and a shortage of food, but this was not from overpopulation, it arose from loss of resources to a conquering foe; and external difficulties provoked internal tension between different political groups, especially in Miletus. One Ionian city, Teos, after sending out colonies to Abdera in Aegean Thrace and Phanagoria in the Black Sea, became so depopulated that Abdera was asked to send people back to refound the mother-city.

We have a few inscriptions, such as foundation decrees of the Late Archaic period, which describe the process and formalities of founding a colony; the vast majority of the information comes, however, from Classical and later authors. Some colonies were established by a mother-city (metropolis) as an act of state, others as a private venture organized by an individual or group, in each case choosing an oikistes (leader/founder of the colony), from no particular group or class but in many cases a nobleman. The oikistes then consulted the Delphic Oracle in order to obtain the approval of the gods for his venture: the colony would be a new home for the Greek gods as well as for the settlers. The colonists and those who stayed behind bound themselves by a solemn oath not to harm each other (initially, colonies reproduced the same cults, calendars, dialects, scripts, state offices, and social and political divisions as in their mother-cities). The oikistes was a very important man. According to sources of the Classical period, it was he who named the new city, as well as selecting its precise site when the party arrived at its destination; he supervised the building of the city walls, dwellings and temples, and the division of land. The death of the oikistes may be seen as the end of the foundation process: he became a hero and his tomb was worshipped with rituals and offerings.

It was a widely held opinion, based mainly on the information of Classical authors, that only males set off to colonize; and that Greek men took local women. Of course, intermarriage was practiced and many ventures may have been entirely male, but we know that women (priestesses) accompanied men in the foundation of Thasos and Massalia. It is also possible that women followed their men to a colony once it had been established. In any case, we have no evidence from the Archaic sources to be certain one way or another.

The relationship between the colonists and the native inhabitants was very important. Again, there is no single model. Unfortunately, in modern scholarship, ‘political correctness’ has cast a shadow. The word ‘barbarian’ has fallen from favor because of its modern connotations; we forget how the Archaic Greeks used it - onomatopeically for the sound of local languages to their ears. Thus, ‘barbarian’ had no cultural connotations; it meant simply someone who did not speak Greek. Modern academics have even set up an artificial dichotomy of ‘Greeks’ and ‘Others’. Scholars are increasingly applying modern definitions and standards of ethnicity and race to the Archaic colonial world (even the concept of ‘Greek-ness’ itself belongs to the Classical period, not earlier). Step by step the attitude is fading (and rightly so) that Greeks ‘civilized’ the local peoples with whom they came into contact. All relationships are a twoway process: so, just as locals were influenced by Greeks, Greek colonies adopted and adapted local practices. Now we know that native people played an important role in the foundation and laying out of Megara Hyblaea. In Metapontum some of the first colonists used the simple construction methods of the local population - dwelling-houses were dug partly into the ground; while in the building of the temple in the chora of Sybaris, posts and piss; were used, a technique alien to mainland Greece. These are just a few of many examples. In many cases, Greeks and locals lived alongside each other in a Greek settlement, whether in the western Mediterranean or the eastern Black Sea. Nowadays, there is increased archaeological evidence of Greeks living alongside locals in native settlements far inland: one case in the Scythian lands some 300 miles/500km from the shore, but also in the deep hinterland of Massalia in the south of France.

Many colonies were established in territory either occupied by a local population or close by (see Table 1). Frequently, land for settlement by colonists was given by local rulers. The relationship between the newcomers and the locals was often pacific, to their mutual benefit. Greek craftsmen were employed by local rulers; for example, in the Iberian Peninsula and the Black Sea to produce prestige objects, and even, as is the case in Etruria, to paint tombs, or build fortifications, as in Gaul, or public buildings, as in Iberia (near the colony of Emporion). This was characteristic mainly of Ionian colonization. Elsewhere, things could be less peaceful. In Syracuse, for instance, the local Cyllyrii were serfs, and at Heraclea Pontica on the southern Black Sea, half the local Maryandini were killed and the rest enslaved. This was typical of Dorian colonization. Recent scholarship has started to re-examine the nature and mechanisms of trade relations between locals and colonists - less a matter of commerce, as we understand it now, more of formalized gift-giving and exchange. What we know about the locals and their culture is mainly the way of life of their elites; and the tastes and behavior of nobles were practically the same in every area, whether of the Mediterranean or the Black Sea (see Europe, South: Greece; Asia, West: Archaeology of the Near East: The Levant).

World History

World History