To the uninitiated, the Arctic is a vast expanse of featureless tundra, mountains, or sea ice that seems at first glance inimical to human life. Yet, within this sea of uniformity is a surprising diversity of landforms, geography, biota, marine conditions, and climates. The region itself is huge. Ranging from 51° N in southern Labrador to 83° N in North Greenland, Arctic tundra and shrub tundra encompass mountains, plains, deserts, and bogs, and host a diverse biota of land and sea mammals, avifauna, invertebrates, fish, and - not least - a plague of insect pests. These resources are not distributed evenly, spatially or seasonally. While humans can easily starve in winter on the interior barrens, the nearby coast may be alive with food resources. Some areas devoid of life for months erupt into a cornucopia of food during a brief season of abundance each year, while others are permanent ecological hot spots (see Seasonality of Site Occupation). In addition to seasonality, weather - always the Arctic wild card - has a huge impact on animals and their availability to hunters. Although Arctic regions are less diverse than temperate and tropical regions, some species are present in great concentration. Subarctic and Arctic marine zones have more diverse food chains and greater number of species than northern forest and Arctic tundra regions, and therefore have greater ecological and cultural stability, while the latter have simple food chains, low species diversity, and frequent disruptions from fire and winter icing, and their boom-and-bust population cycles make human life precarious.

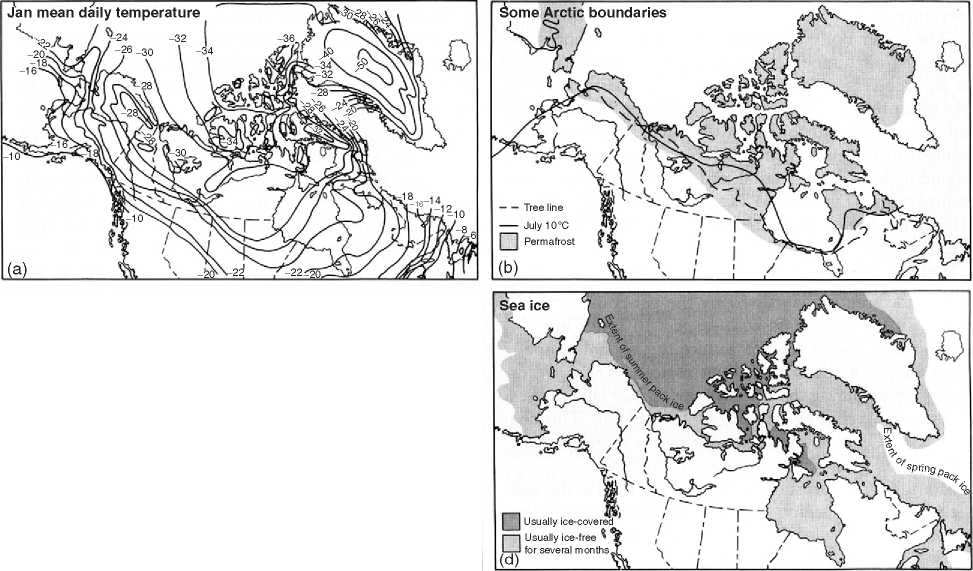

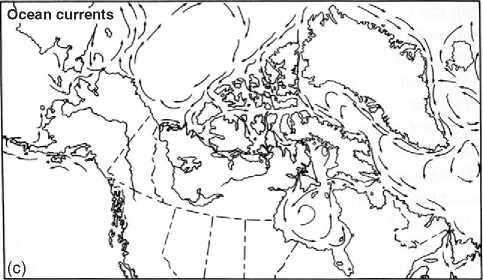

Figure 2 Physical parameters of the North American Arctic (courtesy of Smithsonian HNAI 1984/Arctic, vol. 5, p. 30, fig. 1).

Aleutian Pacific Southwest Chukchi North Central High Arctic Labrador Islands Coast & Alaska Peninsula Alaska Arctic Greenland Kodiak I

To survive under these conditions, Arctic peoples developed variants of four major ethnographic adaptation types: (1) specialized adaptations to caribou hunting on the northern interior (Nunamiut and Caribou Inuit); (2) specialized adaptations to coastal and marine resources (Aleut, St. Lawrence Island Yupik); (3) generalist adaptations involving dual economies with winter hunting on the interior and summer hunting and fishing on the coast (Inupiat Eskimos, Central Inuit); or (4) herding of domestic reindeer, a technology not practiced in North America but prevalent in Eurasia.

Resource-rich areas like the Bering and Chukchi Seas, Foxe Basin-Hudson Strait, and Davis Strait-Labrador Sea have supported human populations on a long-term basis and fostered some of the highest levels of Arctic cultural development. River outlets where fish, seals, and white whales congregate also have high population potential. Other areas, including much of the Canadian High Arctic and northern Greenland, have few resources and little or episodic settlement history. Over-hunting by humans - either by itself or superimposed on natural animal or climatic cycles that resulted in freezing of polynias (ice-free zones) or icing of ungulate foraging grounds - has been a frequent cause of human extinction or abandonment in High Arctic regions. Similar catastrophes occurred in Alaska due to severe storms, volcanism, earthquakes, and tidal waves.

Resource variation that results in ecological ‘patchiness’ has led archaeologists to use ecological and biogeographical concepts like ‘hot spots’, ‘core areas’, ‘peripheries’, and ‘voids’ to help interpret Arctic culture history. In general, long-term settlement and continuity occurs in areas where animal resources are more predictable and abundant. In contrast, resource-poor or unstable regions tend to have episodic settlement history and less cultural and demographic continuity. For these reasons, human communities in the Arctic tend to be widely spaced and have low populations, except in the most productive resource zones. Early contact population sizes closely follow scaling factors determined by resource abundance and predictability, and these gradients also determined limits on cultural complexity and sociopolitical development. Extremely high population levels, complex art, social hierarchies, warfare, and presence of craft specialists found among Northwest Coast and Pacific Eskimo cultures are more weakly expressed north of the Aleutians in Alaska and are even less well-developed in the Central Canadian Arctic and Greenland. However, these patterns are only general tendencies; variation in technology, social conditions, human response, leadership, and a host of other conditions intersect ecological constraints (see Cultural Ecology). Instances of artistic florescence have occurred in the midst of economic and social privation, as seen during a period of starvation at Ammassalik in East Greenland in the late 1800s, or the blossoming of Late Dorset art during a period of climatic change and cultural upheaval c. AD 1000-1300.

World History

World History