Angkor, meaning holy city in Sanskrit, comprises a complex of cities, temples, and reservoirs located north of the Great Lake (Tonle Sap) in northwest Cambodia. It was first encountered by Europeans in the sixteenth century, when Portuguese missionaries visited and described an abandoned stone city, encroached by the jungle. Their accounts were recorded by Diogo da Couto and archived in Lisbon. The Great Lake is one of the world’s most productive sources of freshwater fish. During the wet season, the Tonle Sap River, which connects the lake with the Mekong River, reverses its flow and backs up to expand greatly the lake’s area. With the dry season, the river drains the lake, and rice can be grown in the wetlands left as the lake level falls. The lake margins are a particularly favorable place for settlement by rice farmers and fishers, and the region of Angkor is further attractive because of the perennial rivers that cross the flat floodplain from their source in the Kulen uplands to the north.

There is a long history of settlement in this area, which began at least as early as the Bronze Age, for prehistoric occupation of this period has been found in the Western Baray or reservoir. An Iron Age site has also been found in the vicinity of the temple of Baksei Chamkrong.

Hariharalaya, the earliest major complex, lies to the southeast of Angkor. It comprises a series of temples to the south of the Indratataka, a reservoir of unprecedented size (3800 x 800 m2). Most of the buildings were constructed during the reign of King Indravarman (AD 877-889). His capital incorporated two major temples, known as Preah Ko and the Bakong. The water of the Roluos River was diverted to fill the Indratataka, and was then reticulated to service the extensive moats which surrounded the temples as well as, presumably, the royal palace. Preah Ko is surrounded by a 50-m-wide moat west of the Srah Andaung Preng, a basin 100 m2. The central area is dominated by six shrines dedicated to Indravarman’s ancestors.

The adjacent Bakong stands out for the sheer scale of the conception: the central pyramid rises in five stages within a double-moated enclosure 800 m2. Eight small sanctuaries were placed round the base of the pyramid, probably acknowledging the male and female ancestors of Indravarman. Still awesome, it would have been a potent symbol of royal power and sacred ancestry.

With the death of Indravarman in AD 889, his son Yashovarman (protege of glory) completed the northern dyke of the Indratataka and had the Lolei temple constructed on an island in the middle of the reservoir. However, he founded a new capital centered on a low sandstone hill known as the Bakheng. This center, known as Yashodarapura, the city of Yashovarman, lies at the heart of Angkor itself. Access to the summit temple is by steep stairs, but the top of the hill has been partially leveled, so that the six terraces of the sanctuary rise from the plateau like a crown. There are numerous brick chapels at the base of the pyramid and on the terraces. The topmost tier incorporates five temples, the largest in the center and the others at each corner.

Yashovarman was responsible for the creation of the Eastern Baray, the dykes of which are 7.5 x 1.8 m2 in extent. Inscriptions erected at each corner record the construction of this reservoir fed by the Siem Reap River, which, when full, would have contained over 50 million m3 of water. He also had at least four monasteries constructed south of his new reservoir, and temples on hills surrounding the capital.

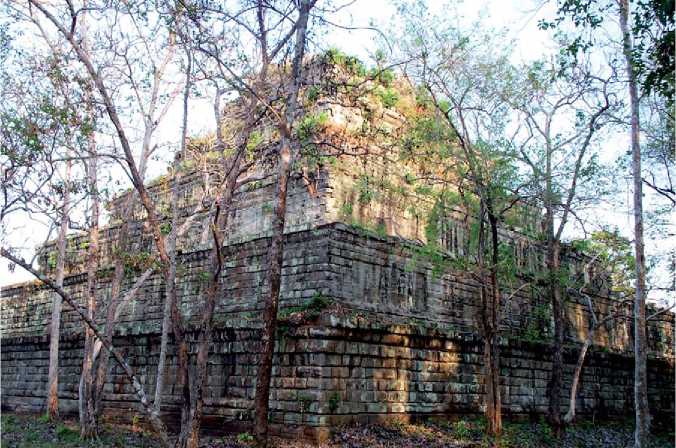

After a brief interlude, when King Jayavarman IV established his capital at Koh Ker (Figure 5), to the northeast of Angkor, his successor and older brother, King Rajendravarman, returned to the old center and had two major state temples constructed. One is now known as Pre Rup, while the Eastern Mebon was

Figure 5 Jayavarman IV of Angkor (reigned AD 928-942) moved his capital to Koh Ker, then known as Lingapura. This massive temple mausoleum dominates the plain for miles in every direction.

Built on an island in the center of the Yashodharata-taka. The former honored the king and his ancestors within the context of the god Shiva. Rajendravarman was succeeded by his ten-year-old son Jayavarman V. He continued to reign at Angkor, and his state temple, then known as Hemasringagiri or the mountain with the golden summits, was built to represent Mount Meru, the home of the Hindu gods.

Jayavarman V’s reign was followed by a period of civil war which left the state in serious disarray. The victorious king, Suryavarman I, established his court at Angkor, the focal point of his capital being the temple known as the Phimeanakas. It comprises a single shrine, surrounded by narrow roofed galleries on top of three tiers of laterite each of descending size. The royal palace would have been built of perishable materials, and will only be traced through the excavation of its foundations. These buildings were located within a high laterite wall with five entrance pavilions ascribed to this reign, enclosing a precinct 600 X 250 m2 in extent. Today, a great plaza lies to the east of this walled precinct. On its eastern side lie the southern and northern khleangs, long sandstone buildings of unknown function. The former belong to the reign of Suryavarman I.

Suryavarman also underlined his authority by beginning the construction of the West Baray, the largest reservoir at Angkor, and one still retaining a considerable body of water. This reservoir was unusual, in that the area within the dykes was excavated, whereas the customary method of construction entailed simply the raising of earth dykes above the land surface. The Western Mebon temple in the center of the baray was built in the style of Suryavarman’s successor, Udayadityavarman.

It was under the succeeding dynasty of Mahidhar-apura, from about AD 1080, that central Angkor reached the present form. Angkor Wat, the largest religious monument known, was constructed by Suryavarman II (AD 1113-1150). A devotee of Vishnu, the temple still houses a large stone statue to this god, which was probably originally housed in the central lotus tower. Angkor Wat incorporates one of the finest and longest bas-reliefs in the world, and the scenes do much to illuminate the religious and court life of Angkor during the twelfth century (see Figures 6 and 7). One scene, for example, shows the king in council, another reveals the Angkorian army on the march, while a third shows graphic scenes of heaven and hell. Very high status princesses are seen being borne on palanquins (Figure 8). Within the walls of reliefs, the temple rises to incorporate five towers, representing the five peaks of Mount Meru, home of the Hindu gods. Despite its size and fame, Angkor Wat remains controversial. Sixteenth-century Portuguese visitors described an inscription that may well have been the temple’s founding document, but this has not been seen or recorded since. We do not know if the entire complex was sacred with restricted access, or whether people resided within the area demarcated by an outer wall and moat. The function of the temple is not known with certainty, but George

Figure 6 The five towers of Angkor Wat rise up above the jungle in this view from the Bakheng temple.

Figure 7 The central five towers of Angkor Wat represent the peaks of Mount Meru, home of the gods.

Cffid(;s has argued that it was a temple and a mausoleum for the king, whose ashes would have been interred under the central shrine.

A second king of the Mahidharapura dynasty, Jayavarman VII (AD 1181-1219), was responsible for the construction of Angkor Thom, the rectangular walled city which today dominates Angkor. This moated and walled city centers on the Bayon, an extraordinary edifice embellished with gigantic stone heads thought to represent the king as Buddha. He also ordered the construction of the Northern Baray or reservoir and the central island temple of Neak Pean, formerly known as Rajasri. According to contemporary inscriptions, visitors to this temple would wash away their sins in the water that gushed from four fountains in the form of a human and animal heads. Foundation inscriptions also describe how Jayavarman VII founded and endowed two vast temple complexes, Ta Prohm to his mother and Preah Khan to his father. Each temple also incorporated shrines dedicated to ancestors of the aristocracy (Figure 9).

Following the death of Jayavarman VII, building activity slowed. By the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the Angkor state was under stress from the

Figure 8 An Angkorian princess, seen on a relief on the walls of Angkor Wat, is carried through a forest on a palanquin.

Figure 9 Banteay Chmar is a huge temple mausoleum, built by Jayavarman VII of Angkor (AD reigned 1181-1219). Located in a remote part of northwest Cambodia, it was, until recently, virtually inaccessible and covered in jungle.

Encroaching Thais, and was abandoned in the middle years of the latter century. While much of the site was then overgrown by the jungle, Angkor Wat was never completely abandoned. It, and indeed all other temples, retain their sanctity to this day.

The physical remains of the civilization of Angkor, and the corpus of inscriptions (Figure 10), make it clear that there must have been many specialists engaged in regular activities. The construction of a temple even of relatively humble proportions would have called on architects and a wide range of laborers, from those who manufactured bricks, to those who cut and shaped stone, as well as carpenters, plasterers to create the frescoes, painters, and gilders. Surviving bronzes, for example, palanquin fittings and statues, indicate the presence of metal workshops, and the ornate jewelry seen on the elite in the bas-reliefs reflect not only lapidaries but workers of gold, silver, and precious stones.

Recent archaeological research by Roland Fletcher and Christophe Pottier has greatly expanded our conception of Angkor. They have identified numerous

Figure 10 The temple of Banteay Chmar contains bas reliefs showing a naval battle between the Kingdom of Angkor and the Chams.

Temple foundations and evidence for occupation beyond the ceremonial central temples and reservoirs, suggesting that this was one of the largest preindustrial cities known. Moreover, they have traced Angkorian canals that issued from the reservoirs, providing firm evidence for intensive irrigation of the rice fields between the city and the Great Lake to the south. North of Angkor, it is clear that major water control measures were put in place to divert water via the newly created Siem Reap River, and bring the precious water to the central city to feed the reservoirs and canals. Precisely when this expansion and the provision of the irrigation canals took place within the Angkorian period remains under investigation, but the hydraulic expertise was clearly of a very high order indeed.

World History

World History