Baseline Geospatial Constructs

Modern landscape or environmental archaeology is an amalgam of techniques and ideas from several disciplines (geography, ecology, archaeology, pale-nology, paleoclimatology). Some of these were derived from social science and theory, others from hard sciences dealing with the earth and environmental history. This treatment focuses on the ecologically contextual, geospatial, and diachronic analysis of human-landscape interactions. The specialized topics of ‘spiritual landscapes’ and ‘architectural landscape archaeology’ are beyond the scope of this discussion.

Prior to WWII, it was not uncommon for archaeologists to spend their entire careers studying a single site, treated almost in isolation - isolation from other contemporary sites and in isolation from the environment and landscape features surrounding it. Furthermore, following the Linnaean tradition of focusing on the identification of new ‘species’ (and in the case of archaeology, new material culture and artifact ‘types’), the study of prehistoric cultures was often done with little or no reference to current or past environment or topographic setting. Environmental context was not a baseline concern. In both the Americas and Europe, between the 1950s and 1970s, two streams of thought coalesced to form the conceptual and methodological building blocks of contemporary landscape archaeology. In the United States, the roots of a ‘regional’ approach in studying prehistoric settlements can be traced back to Lewis Henry Morgan’s work on Native American village organization (1881) and to Julian Steward’s 1930s study of the shifting hunting and gathering economy of the Shoshone Indians. Despite these early prototypes, modern American students did not begin to focus on the distribution and context of archaeological sites until the release of Gordon Willey’s 1953 survey work in the Viru Valley of Peru. While many parallel studies were done in Mexico and North America, it was Willey’s study of changing ‘settlement patterns’ in an arid coastal valley that set the form and direction of later spatial studies in American archaeology.

At the same time, other baseline assumptions that helped form landscape archaeology came from biology and early efforts to explain how organisms and multiple communities of animal and plants formed a system of interconnecting elements. In 1953, Eugene Odum published Fundamentals of Ecology and introduced the concept of nonstatic or dynamic ‘ecosystem’ into the biological lexicon. The same year, Odum’s essay, Human Ecology, extended this biological concept to the study of human populations and culture. These intellectual constructs also served to infuse the idea of change and process to the often static treatment of human-landscape interactions.

In Europe, one of the first conceptual attempts to incorporate the notion of environmental context emerged with the introduction of the concept of ‘site catchment area’. In 1972 this concept was borrowed and applied from earlier social and economic models by two archaeologists, Higgs and Vita-Finzi. The notion of site catchment area provided a functional, economic, and geographic framework to relate land-use patterns to environmental conditions and subsistence sources. It also assumed that these subsistence activities took place within a circumscribed environmental context that would diminish in intensity and importance with increasing distance from the core site area.

While the European ‘ecological catchment’ and the American ‘settlement pattern’ were spawned from different traditions, in the 1970s and 1980s archaeologists on both sides of the Atlantic borrowed freely and both concepts helped set the stage for later regional - and habitat-oriented treatments of archaeological data. Their adoption represented a paradigm, or conceptual, shift away from objects and ‘things’ (including ‘sites’), in and of themselves, to broader contextual investigation of spatial associations and interrelationships ‘between’ things, artifacts, sites, and resource areas.

By the middle of the last decade, landscape archaeology began using constructs that attempted to weld process and landscape in a single model or paradigm. Archaeologists working in Mesoamerica adopted a new model, the Tropic Web, that integrates the ‘spatial’ aspect of ‘site catchment’ with the ‘dynamic’ elements of ‘ecology’ and change. This ‘dynamic and geospatial’ framework treats humans as elements of a network of resources and organisms that are intensely linked throughout their life cycles. A related concept, Task Space, was fielded by African archaeologists which treats landscape as a place where different tasks take place at specific times within a changing set of schedules. Both ideas also provided conceptual tools that began to ‘fit’ with the dynamic, real time, real world, 3D modeling capabilities of current geospatial technologies.

Applied Technology: Dating and Proxies

These mixed traditions and approaches resulted from two impetuses toward a regional geospatial and environmental perspective: (1) the availability, beginning in the 1960s, of high-resolution aerial photography; and (2) externally imposed legal mandates to undertake regional archaeological surveys as part of the emerging environmental impact and historic preservation movement in developed regions. These new tools and procedures, in turn, aided archaeologists in seeking and discovering new sites in environmental contexts they may not have been otherwise investigated.

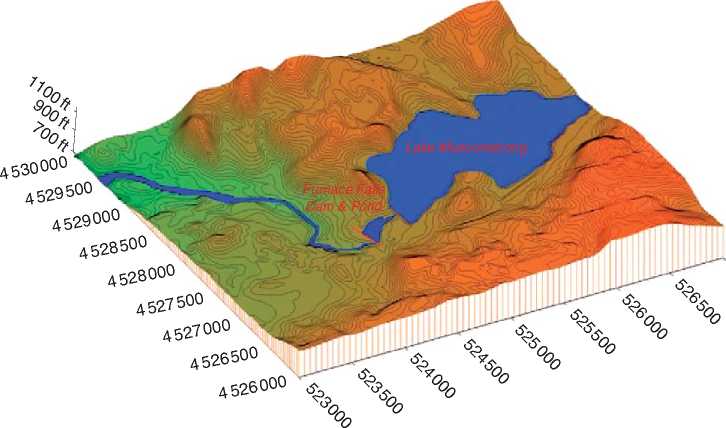

Finally, just as the availability of low-altitude aerial photography in the 1960s provided archaeologists with handy geospatial tools for evaluating sites in an environmental context, the recent availability of high-resolution, radar-derived digital terrain models are today providing the capability to investigate and explore - remotely and safely - a study area from afar (Figure 1) (see Cultural Ecology; Cultural

Figure 1 3D Digital Elevation Model (DEM) of a Highlands valley of New Jersey, U. S. The radar-derived coordinate and elevation data can be rendered as either two-dimensional contours, or as three-dimensional surface mesh models which permit the extraction of plan, profile and volume information for the analysis of the topographic and ecological context of historic and prehistoric sites within the drainage. (By Joel W Grossman, Ph. D., © Joel W Grossman, Ph. D. 2008. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.)

Resource Management; Landscape Archaeology; Paleoenvironmental Reconstruction, Methods; Remote Sensing Approaches: Aerial; Geophysical; Settlement Pattern Analysis; Settlement System Analysis; Paleodemography).

The ability of modern landscape archaeology to measure either environmental change, and/or man’s impact on it, partially resulted from the emergence of new dating techniques that have resolved increasingly finer units of analysis-from intervals of centuries, down to sampling and dating at 10-50-year intervals, or in the cases of tree rings, clay varves, and ice cores, intervals of 1 year. The majority of case studies highlighted below represent often radical reinterpretation of prehistoric man-landscape interactions, based on data from terrestrial and marine cores that are yielding both chronological and environmental evidence. These procedures, and the incorporation of techniques and data from other disciplines, are central to the following examples and case studies. Each in turn demonstrates the use of two elements: (1) subdecade-level dating with chronometric procedures (of these, perhaps the most important technological innovation was the advent of Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (AMS) radiocarbon dating in the 1980s which both addressed the crude dating of early C14 techniques and enabled high resolution age determinations from samples as small as a charred seed; or from the counting of tree ring, ice or sediment layers from long core sample) (see Archaeometry; Carbon-14 Dating; Dendrochronology; Electron Spin Resonance Dating; Luminescence Dating; Obsidian

Hydration Dating) and (2) the use of what environmental scientists refer to as proxies. Proxies are subtle traces of minerals, radioactive elements, or organic compounds that show changes indicative of temperature or climatic shifts (see Archaeometry; Chemical Analysis Techniques; Geoarchaeology; Neutron Activation Analysis; Paleoethnobotany; Pollen Analysis). The following cases will stress the analytical basis for each set of climatic findings over individual theories or models.

Old Biases and Impediments

The emergence of modern landscape archaeology and the understanding of the delicate and dynamic balance between human and natural forces did not come easily. The new perspectives of landscape archaeology or environmental history could not emerge until several key deeply held biases and culture-bound Western assumptions had been set aside. These were (1) the concept that preindustrial environments were pristine and unspoiled, and that the Holocene, or last 10 000 years following the retreat of glaciers, underwent little change and was static and (2) that indigenous peoples lived in child-like harmony with their environment.

The notion of a pristine and stable or static past The

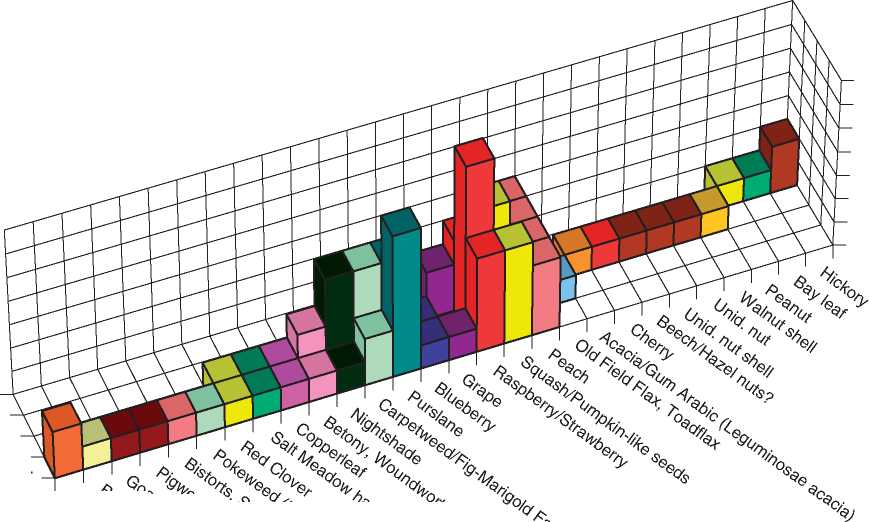

First major barrier came from ingrained nineteenth-and twentieth-century assumptions that colonial environments were, prior to the recent impacts, stable and reflected habitats and groundwater conditions unchanged for thousands of years. A second major assumption to be set aside was that in addition to being pristine, little if any environmental change had taken place since the retreat of the ice sheets 10 00012 000 years ago - what existed in the historic period had existed for thousands of years before. This notion arose in part from bias, and in part from imprecise available data control and dating techniques. It was only in the early 1970s that two pivotal document-based studies of the colonial environment of North America - Crosby’s The Columbian Exchange and William Cronon’s Changes in the Land - began to plant the seeds of reevaluation. Not only had the landscape been impacted by European contact in the early fifteenth century, but also that it had been altered, if not at times carefully managed, by Native Americans long before European introductions. Cronon even suggested that what many early explorers described in exotic travelogues as the ‘natural untouched splendor’ of America’s eighteenth-century wilderness may have been artifacts of a generation of abandonment by Native Americans after their populations had been decimated by disease and/or pushed out of their traditional territory by European colonists. In fact, it now appears that the traditional use of these eighteenth-century documentary accounts may not be as accurate as the well-dated botanical remains from the seventeenth-century archaeological sites. As summarized below, both the excavation of archaeological plant remains from mid seventeenth-century deposits and recent pollen sequences from the Mid-Atlantic region of the Eastern United States have documented plants indicative of disturbed environments as early as 1650 (Figure 2).

The notion of the ‘native in harmony with nature’

Coupled with the misconception of supposedly stable pre-European environments of colonized territories in Africa, Asia, and America, was the associated bias that not only were the indigenous living in a ‘stable balance with nature’, but also that they were too ‘primitive’ and limited in numbers to cause any significant changes to their surroundings. That picture is no longer valid. Archaeological ground surveys and air photo analysis, for example, now suggest a

Early 19th c. Early 18th c. Late 17th c. Mid. 17th c

Figure 2 Three Dimensional bar graph of dated plant remains from the 17th and 18th Century features discovered in the Dutch West India Company Block at Pearl Street in Lower Manhattan, New York (Grossman et al. 1985). The predominance of ‘‘weed’’ types introduced from Europe, predominantly adopted to ‘‘Waste Ground’’, suggests that the environment of Dutch New York had been disturbed and traumatized at least as early as the mid-17th Century. (By Joel W Grossman, Ph. D., © Joel W. Grossman, Ph. D. 2008. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.)

Mayan population of some 3 million people, and that at least 8000 kilometers (out of a total of 22 700 square kilometers, or 35% of their area) had been cleared and deforested by the Classic Period Maya. Instead of being sparsely populated as many early explorers recounted, these low densities may reflect only the sudden and drastic impacts of disease on indigenous peoples. Some early diaries of the first Spanish visitors to Peru described a 90% population decline along the coast, and coastal valleys devoid of people. Current estimates put New World population levels at 40-70 million inhabitants at the time of European contact. As is the case today, the higher the density of people, the greater the environmental impact, all things being equal.

World History

World History