After the expulsion of the Hyksos the pharaohs of the Eighteenth Dynasty set out to form one of the most powerful states in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Near East. Internal reforms and a restructuring of the administration and military enabled Egypt to march into and occupy foreign territories where she installed her own administration. Dozens of military campaigns in the Levant are recorded by pharaohs such as Amenophis II and especially Thutmosis III, who ruthlessly exercised his imperialistic policy. The eastern desert of Upper Egypt and increasingly Lower Nubia became the classic gold sources of Egypt. Large-scale expeditions were sent out to mine turquoise and copper in the Sinai Peninsula. The southern border of Egypt was set as far south as Gebel Barkal, a trading and religious center near the fourth cataract. Trade relations were maintained throughout the Mediterranean and pottery from Cyprus, Crete, Mycenae, and the Levant can be found at many sites in Egypt. By the time of the reign of Amenophis III (c. 1390-1352 BC), a prosperous, wealthy, and influential Egypt had reached its first New Kingdom zenith. This period, however, also saw domestic turbulence and turmoil arising from the religious reforms of Akhenaten (c. 1352-1336 BC), the son of Amenophis III, who abandoned the old pantheon and installed the god Aten as the sole god for Egypt. Early in his reign Akhenaten severed all links with the religious capital of Thebes and its principal god Amun by relocating the capital to Akhetaten (Horizon of Aten), modern Tell el-Amarna. Worshipping one god only was a profound disturbance for ordinary Egyptians who had always been used to having direct contact with many gods. Consequently, when Akhenaten died, so also died his religion of the Aten. Under Tutankhamun (c. 1336-1327BC), the first attempts at a religious restoration of the old cults were launched while during the subsequent Nineteenth Dynasty, there ensued an active persecution of the Aten cult. In the administration many civil officials were replaced by military personnel and the army became the most influential domestic power. Internationally, Egypt was faced with the expansionist Hittite empire and they finally clashed at the Battle of Qadesh where the army of Ramses II met the-Hittite troops of Muwatalli. Ramses II did not achieve his goal of driving the Hittites out of Qadesh and the whole campaign ended in a stalemate that resulted in a peace treaty in the twenty-first regnal year of Ramses II. After this Egypt had a relatively calm and prosperous period until the so-called Sea Peoples caused serious turmoil in the eastern Mediterranean at the end of the thirteenth century BC. First Pharaoh Merenptah (c. 1213-1203 BC) and later Ramses III (c. 1184-1153 BC) had to fight battles against the Sea Peoples on land and at sea in order to secure Egypt’s sovereignty. These international disruptions were too great, however, and combined with internal economic problems Egypt began losing her international power. At the end of the New Kingdom Egypt had to withdraw from the Levant altogether.

Tell el-Amarna

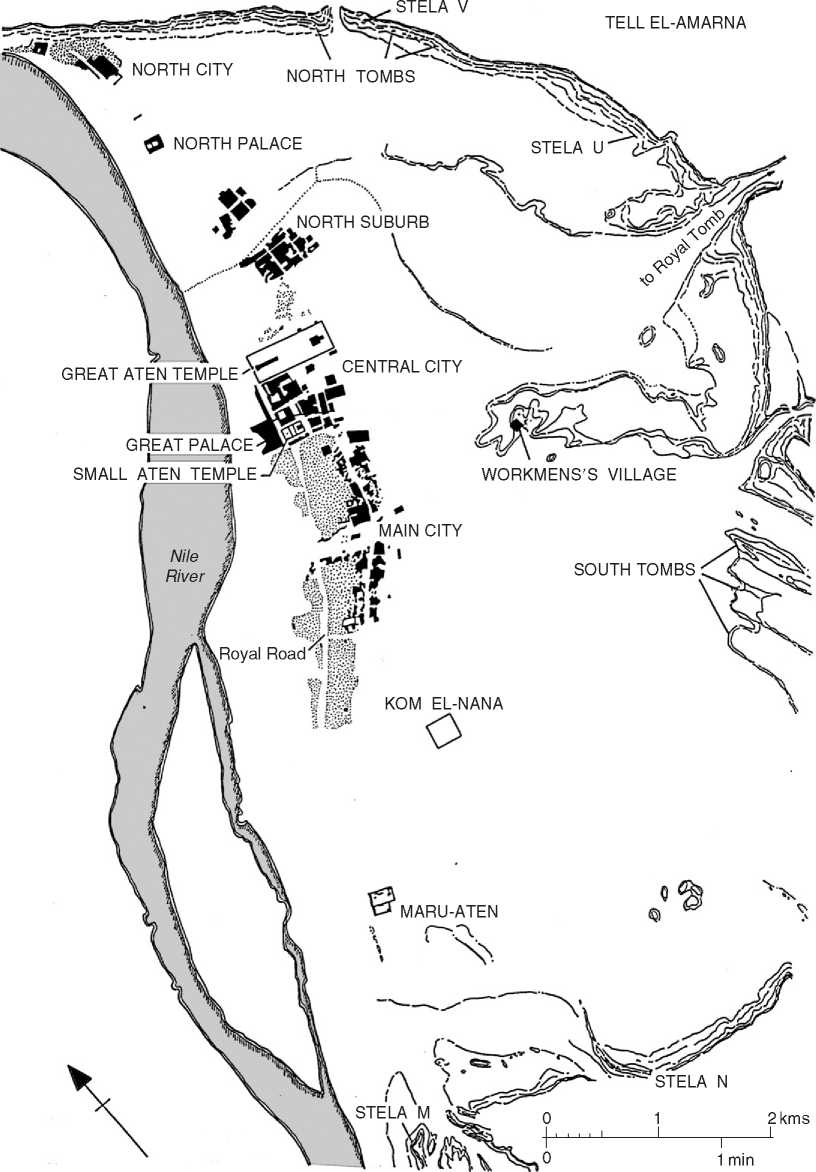

The city of Amarna was built on virgin soil and covered an area of about 13 x 5km (Figure 8). The city was made up of palaces, houses, and temples which had to be built quickly to accommodate the many thousands who were to move there from Thebes. A major royal road running north-south was built and it was flanked by palaces and temples. Some temples like the so-called House of the Sun Disk were up to 750 m long and 230 m wide. They housed hundreds of altars for the offerings to Aten. Palaces were lavishly decorated and spread throughout the city. Private houses were located in the suburbs to the north and south of the Central City. Some larger houses or villas had more than forty rooms covering more than 1000 m2. The standard design was tripartite with two public sections consisting of a vestibule, long hall and central hall. The third section was the private area with bedrooms and bathrooms. Around these villas were clusters of smaller houses. Remarkably, the houses at Amarna differ in size rather than design, and most features were constantly repeated. By no means should Amarna be seen as an organic settlement however, since its standardization was mostly due to the time pressure of building the city.

Deir el-Medineh

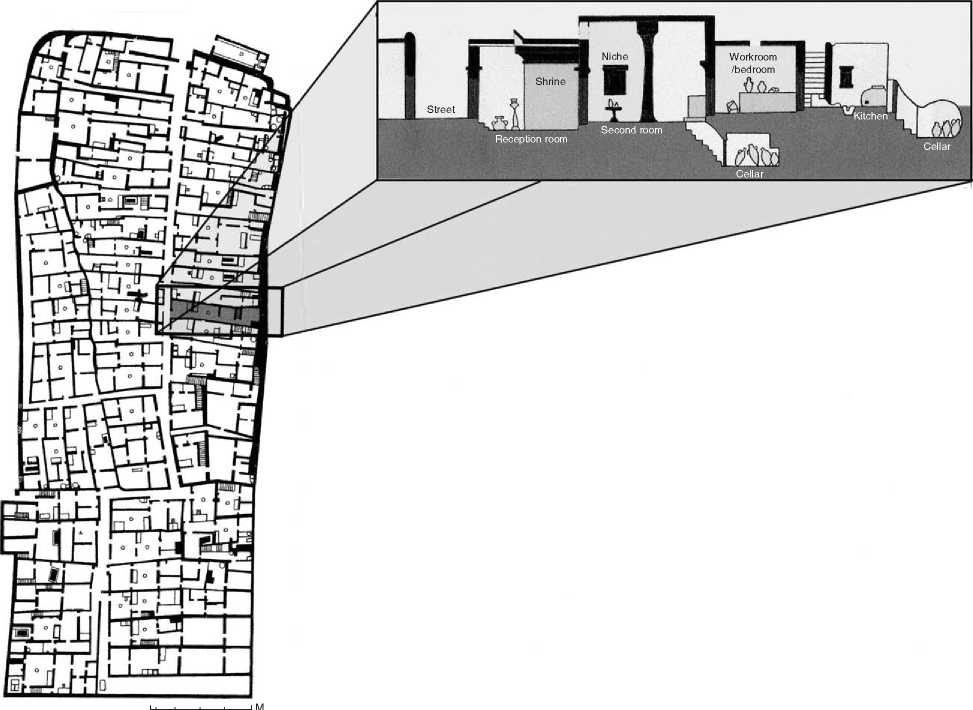

The workmen’s village of Deir el-Medineh was founded under King Thutmosis I (c. 1504-1492 BC) in order to house the men who built the royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings (Figure 9). It was a state-run community where almost all supplies for daily life were provided by the crown. At its peak the village consisted of some 70 houses alongside the main road and was surrounded by a 6-7 m high enclosure wall. Forty to fifty houses were built outside the compound. An average house had four rooms with an entrance room 40-50 cm below street level. The original houses were complete mud-brick structures without foundations. Later houses had a basement of stones and sometimes stone walls extending up to 2.5 m in height. The major feature in the entrance area was the mud-brick bench-like structure, possibly a small shrine. The next room had one or two columns and it contained a kind of divan. At the rear were the bedroom, the kitchen, and storage facilities. A staircase also gave access to the roof providing further living space. The inhabitants of Deir el-Medineh were buried in tombs on the hill slope nearby. The tombs had a superstructure with a chapel which was sometimes crowned by a small pyramid and a substructure with a shaft and a burial chamber that was often colorfully decorated. Next to the village around 5000 limestone flakes and broken pottery sherds were found with many inscriptions from the villagers. They consist, among others, of contracts, files of lawsuits, prayers, and school texts. In conjunction with the archaeological evidence and other papyri concerning Deir el-Medineh, the settlement has become the best-known village of the Late Bronze Age. The village was abandoned under Ramses XI (c. 1099-1069 BC) when the Valley of the Kings was also abandoned as the royal burial ground.

Luxor and Karnak Temple

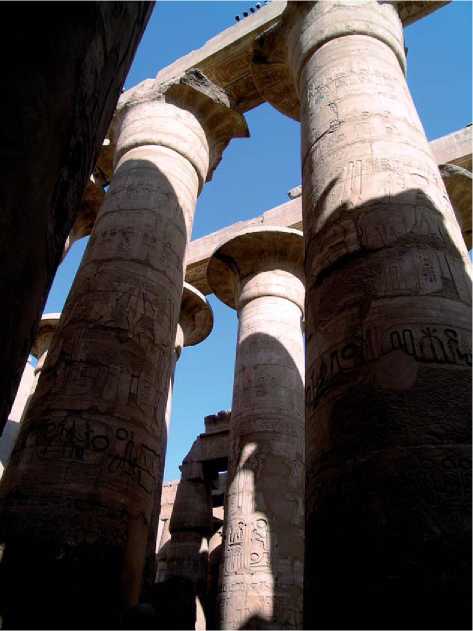

During the early New Kingdom building activity was conducted on all major temples such as Karnak and Luxor Temple. Both temples were located in Upper Egypt at Thebes. The temple at Karnak goes back to the time of Sesostris I and was the major cult center for the Theban triad of the gods Amun, Mut, and Khonsu. From the Middle Kingdom until the Thirtieth Dynasty Karnak remained a site under permanent construction as each pharaoh added and extended to this temple called ‘The most select of Places’ (Figure 10). The continuous addition of pylons (tower-like entrance gates), courtyards, columned halls, obelisks, and chapels means that the temple has to be read archaeologically from the inside out with the oldest part not at the front of the first pylon but almost in the middle of the compound. One of the most impressive buildings at Karnak is the Great Hypostyle Hall with 134 papyrus columns rising up to 21m (Figure 11). The hall was once roofed and illuminated through windows placed high up the wall right under the ceiling. The foundation of the great hypostyle hall goes back to Amenophis III (c. 13901352 BC), but the decoration was initiated under Sety I (c. 1294-1279 BC) and finished under Sety’s son Ramses II (c. 1279-1213 BC). The Great Hall has both raised relief dating to the time of Sety I and sunken reliefs which were generally used on the outside walls to increase the effect of shadow and sunlight. The latter, more economical technique was used during the immense building program of Ramses II.

Figure 8 Capital of Pharaoh Akhenaten at Tell el-Amarna (Eighteenth Dynasty).

The inner walls were reserved for the depiction of The temples of Karnak and Luxor were linked rituals and processions while the outer facades were through a system of roads, each flanked with

Decorated with the campaigns of Sety I and Ramses II sphinxes. As with Karnak, Luxor temple was dedicat-

To Palestine and Syria. ed to Amun or Amun-Ra and dates back to the reign

01 5 10 15 20

Figure 9 Workmen’s village at Deir el-Medineh (New Kingdom).

Figure 10 View over Karnak Temple from east.

Of Hatshepsut (c. 1473-1458 BC) (Figure 12). The core at the southern end was built under Amenophis III. Under Akhenaten work was interrupted at Luxor but resumed under Tutankhamun (c. 1336-1327BC).

Figure 11 Great Hall at Karnak (Nineteenth Dynasty).

The giant pylon was erected by Ramses II and decorated with scenes and texts of the Battle of Qadesh against the Hittites. In the first millennium further additions were made by Shabaka (c. 716-702 BC) who built a kiosk outside the temple, and by Necta-nebo I (380-362 BC) who embellished the sphinx alley with hundreds of statues. Under Alexander the Great the worship of the emperor was established here and this tradition was continued until the Roman period, when the temple finally became a military camp from the fourth to sixth century AD. While the cult at Karnak focused on the worship of the gods, Luxor temple focused more on the worship of the king and his relationship with the gods. Later on, several churches were built in Luxor temple and in the thirteenth century AD, the mosque of Abu el-Hagag, which is still in use today, was built in the first courtyard.

Western Thebes

On the west bank at Thebes in the Valley of the Kings, the New Kingdom pharaohs established their final resting place. As a point of departure from earlier periods, however, the mortuary cult was separated from the king’s actual burial place. Thus, the mortuary temple of each king, with the classic design of a god’s temple with pylons, courtyards, columned halls and inner sanctuaries, was erected at the edge of the river plain. Although the scenes on the walls of these temples show overwhelmingly rituals and cultic activities, they also commemorated historical events such

Figure 12 Luxor Temple from the south with pylon of Ramses II (left), colonnade of Amenophis III/Tutankhamun (right) and the mosque of Abu al-Hagag (center).

As the Battle of Qadesh of Ramses II and the battle against the Sea Peoples by Ramses III.

The tombs consist of a series of descending corridors and chambers cut into the limestone cliff. While earlier tombs have a bent axis, later tombs possess a straight axis echoing the topography of the underworld. The wall decorations show scenes and texts from afterlife books such as the Book of the Dead or the Book of Caverns. Most of the royal mummies were relocated to safer places in the Theban necropolis by the end of the New Kingdom and today many are in the Cairo Museum on display. The most famous tomb in the Valley of the King is that of Tutankhamun. In 1922 it was found largely intact and unplundered and it gives a good insight into the riches that once went into the tombs of the New Kingdom pharaohs, especially in view of the fact that this king was a relatively insignificant ruler.

In western Thebes thousands of higher and lower officials and priests possessed rock-cut tombs. The standard layout during the Eighteenth Dynasty comprised an open courtyard and possibly a shaft, and it was surrounded by a wall (Figure 13). Inside was a broad hall and a corridor giving the whole a T-shaped form. From here sometimes a sloping passage led to the burial chamber underground. During the Nineteenth and Twentieth Dynasties the courtyard often had a pylon and columns while the tomb structure was topped by a pyramid, crowned by a capstone (pyramidion), and attached chapel (Figure 14). A Theban specialty were the so-called funerary cones. They were made of clay and placed on the fac:ade above the tomb entrance. They were stamped on the top with the name of the tomb owner and his titles.

In contrast to Thebes, in the north at Saqqara, tombs of high officials were designed like temples with pylons, courtyards, and columned halls. Scenes of daily life and mortuary rituals characterized the wall decoration at the beginning of the New Kingdom, but over time only religious and mortuary themes tended to prevail.

World History

World History