Although the overall health of Neolithic peoples suffered as a consequence of this cultural shift, many view the transition from food foraging to food production as a great step upward on a ladder of progress. In part this interpretation is due to one of the more widely held beliefs of Western culture—that human history is basically a record of steady progress over time. To be sure, farming allowed people to increase the size of their populations, to live together in substantial sedentary communities, and to reorganize the workload in ways that permitted craft specialization. However, this idea of progress is the product of a set of cultural beliefs, not a universal truth. Each culture defines progress (if it does so at all) in its own terms.

Whatever the benefits of food production, however, a substantial price was paid.25 As anthropologists Mark Cohen and George Armelagos put it, “Taken as a whole, indicators fairly clearly suggest an overall decline in the

25 Cohen, M. N., & Armelagos, G. J. (1984). Paleopathology at the origins of agriculture. Orlando: Academic; Goodman, A., & Armelagos, G. J. (1985). Death and disease at Dr. Dickson’s mounds. Natural History 94 (9), 12-18.

Agriculture The cultivation of food plants in soil prepared and maintained for crop production. Involves using technologies other than hand tools, such as irrigation, fertilizers, and the wooden or metal plow pulled by harnessed draft animals. pastoralism Breeding and managing large herds of domesticated grazing and browsing animals, such as goats, sheep, cattle, horses, llamas, or camels.

Quality—and probably in the length—of human life associated with the adoption of agriculture.”196

Rather than imposing ethnocentric notions of progress on the archaeological record, it is best to view the advent of food production as but one more factor contributing to the diversification of cultures, something that had begun in the Paleolithic. Although some societies continued to practice various forms of hunting, gathering, and fishing, others became horticultural, and some of those developed agriculture. Technologically more complex than horticultural societies, agriculturalists practice intensive crop cultivation, employing plows, fertilizers, and possibly irrigation. They may use a wooden or metal plow pulled by one or more harnessed draft animals, such as horses, oxen, or water buffaloes, to produce food on larger plots of land. The distinction between horticulturalist and intensive agriculturalist is not always an easy one to make. For example, the Hopi Indians of the North American Southwest traditionally employed irrigation in their farming while at the same time using basic hand tools.

Pastoralism arose in environments that were too dry, too grassy, too steep, too cold, or too hot for effective horticulture or intensive agriculture. Pastoralists breed and manage migratory herds of domesticated grazing animals, such as goats, sheep, cattle, llamas, or camels. For example, the Russian steppes, with their heavy grass cover, were not suitable to farming without a plow, but they were ideal for herding. Thus a number of peoples living in the arid grasslands and deserts that stretch from northwestern Africa into Central Asia kept large herds of domestic animals, relying on their neighbors for plant foods. Finally, some societies went on to develop civilizations—the subject of the next chapter.

1. The changed lifeways of the Neolithic included the domestication of plants and animals as well as settlement into villages. How did these cultural transformations solve the challenges of existence while at the same time create new problems? Did the Neolithic set into motion problems that are still with us today?

2. Why do you think some people of the past did not make the change from food foragers to food producers? What problems existing in today’s world have their origins in the lifeways of the Neolithic?

3. Though human biology and culture are always interacting, the rates of biological change and cultural change uncoupled at some point in the history of our development. Think of examples of how the differences in these rates had consequences for humans in the Neolithic and in the present.

4. Why are the changes of the Neolithic sometimes mistakenly associated with progress? Why have the social forms that originated in the Neolithic come to dominate the earth?

5. Although the archaeological record indicates some differences in the timing of domestication of plants and animals in different parts of the world, why is it incorrect to say that one region was more advanced than another?

Childe, V. G. (1951). Man makes himself. New York: New American Library.

In this classic, originally published in 1936, Childe presented his concept of the Neolithic revolution. He places special emphasis on the technological inventions that helped transform humans from food gatherers to food producers.

Coe, S. D. (1994). America’s first cuisines. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Writing in an accessible style, Coe discusses some of the more important crops grown by Native Americans and explores their early history and domestication. Following this she describes how these foods were prepared, served, and preserved by the Aztec, Maya, and Inca.

Diamond, J. (1997). Guns, germs, and steel. New York: Norton. This Pulitzer Prize-winning bestseller addresses the question of the distribution of wealth and power in the world today. For Diamond, this answer requires an understanding of events associated with the origin and spread of food production. Although Diamond falls into various ethnocentric traps, he provides a great deal of solid information on the domestication and spread of crops and the biological consequences for humans.

Mann, C. C. (2005). 1491: New revelations of the Americas before Columbus. New York: Knopf.

Mann dispels the myth of the Americas as an uninhabited wasteland before the arrival of Columbus and the European colonizers who followed him. He shows not only the richness of various Native American cultures but also the devastating effects of colonization.

Rindos, D. (1984). The origins of agriculture: An evolutionary perspective. Orlando: Academic.

This is one of the most important books on agricultural origins. After identifying the weaknesses of existing theories, Rindos presents his own evolutionary theory of agricultural origins.

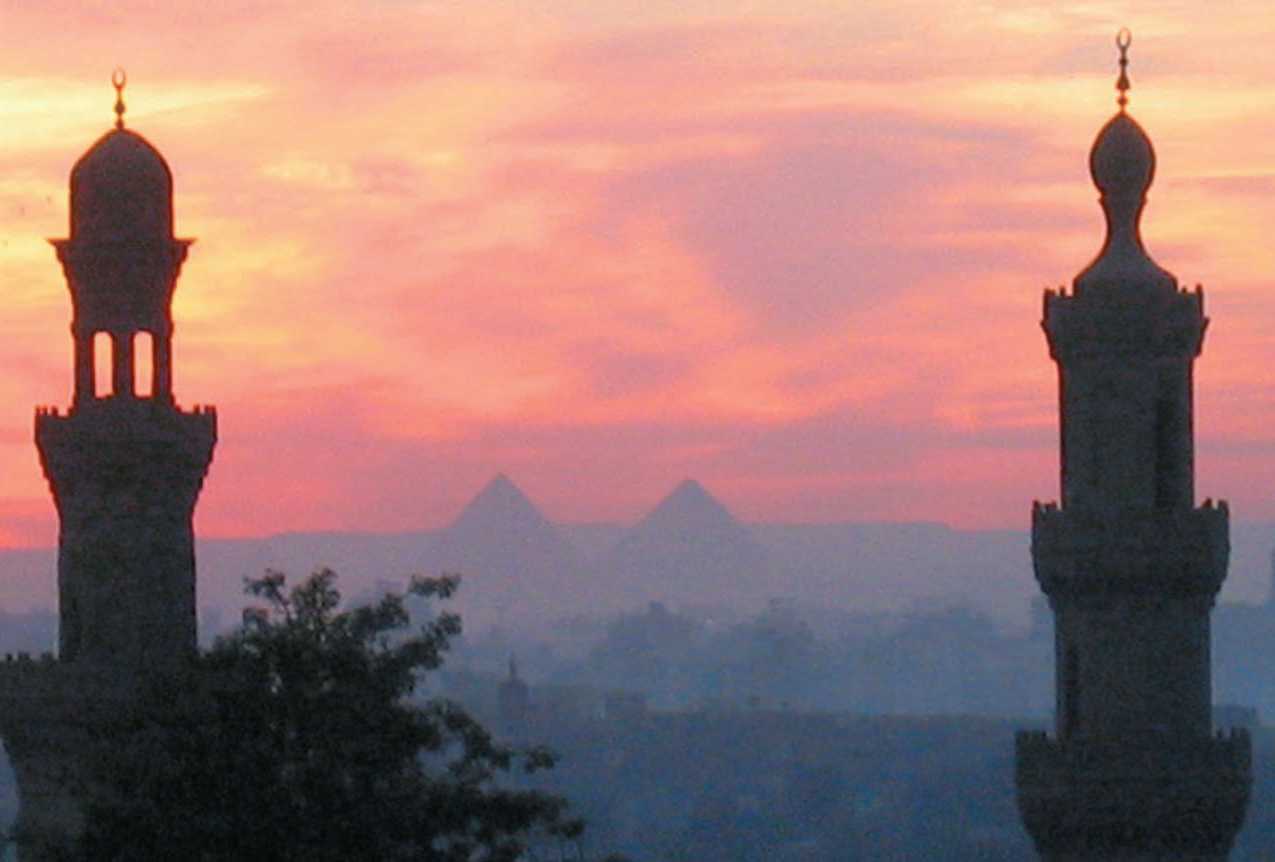

Challenge Issue With the emergence of cities and states, human societies began to develop organized central governments and a concentration of power that made it possible to build monumental structures, such as the great pyramids of Egypt. But cities and states also ushered in a series of challenges, many of which city dwellers still face. For example, social stratification, in which a ruling elite controls the means of subsistence and many other aspects of daily life, exploits many city dwellers and poor people in outlying areas. While the people of stratified societies are interdependent, the elite classes have disproportionate access to and control of all resources, including human labor. In Cairo, as in other big cities, housing, for example, is dramatically different for different social classes. While the elite live in luxurious homes, 5 million urban poor live illegally in tomb rooms of cemeteries known as the City of the Dead.

© Aladin Abdel Naby/Reuters/Landov

World History

World History