Archaeologists have long been divided into two camps, historical and prehistorical (Milanich 2001: xi). As we once again ask ourselves to evaluate the arbitrary divide that has existed between prehistory and history, we are still, in essence, asking about ‘the questions that count’ (Deagan 1988) to both scholars and those they study and revisiting a topic that still needs to be addressed today. Lightfoot’s (1995) discussion focused on the culture contact period, the role of archaeology, and the need to consider the pluralistic context of contact and colonial societies in North America. He noted that several problems exist due to the separation of ‘prehistoric’ and ‘historical’ archaeology by their practitioners, in particular the study of long-term culture change. Although many archaeologists today think of the past in terms of ‘pre-contact’ and ‘post-contact’ (versus prehistoric and historic), in North America substituting one term for another has not changed the fact that these designate the earlier time period as Native American and the later as focused on the presence of Euro-American people and material culture. The division between prehistory and history continues to present a barrier to a fuller, deeper understanding of the past (see Mrozowski, this volume).

This chapter focuses on the question: what does the death of prehistory mean for Native American people of southern New England today? It could represent, most obviously, the end of a dichotomous split between the periods before and after colonization, which defines native history almost exclusively in terms of the European past. Eliminating this divide would offer the ability to see all of humanity (including Indians) as existing in a continuum of time. Or it could present an opportunity for

Native people to define their own history and cultural practices based on which ones they have chosen (or been able) to continue from their past and which ones have been integrated into their dynamic cultures. In this chapter, I consider how archaeologists have studied and interpreted native groups of southern New England and suggest the inclusion of newer cultural practices that reveal the dynamic quality of these contemporary cultures, thus providing a more complete understanding of both the past and present. Establishing that native tribes of today are not ‘remnant’ cultures of a prehistoric past is an important step towards making meaningful connections to the contemporary world, one of the central goals of archaeology today.

Too often the past is equated with tradition when native culture is considered. But what is a tradition? When does it become labelled as such? And who determines what is traditional and authentic? The concept of traditional, or ‘real’, Indians in New England has existed for centuries and still affects how non-native people, including archaeologists, perceive Native Americans and their descendants. The myth of ‘the Indian’ began with Columbus’s encounter with the Tainos and quickly became etched in the American mind along with other nationalistic creations (see Thomas 2000), such as the giving holiday created in the nineteenth century.1 While other populations in the United States transform and change, adopt new customs, and modernize as times and technologies change, Native Americans who are not stuck in prehistory—living in wetus,41 42 wearing regalia, dancing around a fire, or maintaining traditional skills such as basket-weaving—are not considered authentic in contemporary minds or Western epistemologies. When non-native people want a ‘native experience’, they request demonstrations involving clothing, foods, music, and dances that replicate familiar traditions of the 1600s; these expectations become the defining elements of how ‘authentic’ Indians are supposed to be. When native people do not fit stereotypes established by Euro-Americans, they are often branded as inauthentic, especially when political and economic power is at stake.

This chapter discusses the disconnect that exists for many scholars between the imagined Indian and real native people in southern New England and explores examples of more contemporary cultural practices and places on the landscape that, I argue, are as real and traditional as earlier ones because they are used and created by native people and have purpose in their contemporary cultures. Just as importantly, they connect modern-day tribes to their history and past, as they define them. Lightfoot (this volume) examines how we think about and investigate interactions with the environment; our concept of environment should also include homelands and places on the landscape, as discussed in this chapter. Aguilar and Preucel (this volume) also recognize the importance of place-based perspective as essential to the changes necessary to incorporate indigenous knowledge in archaeology. I also argue that modern practices do not have to be (and should not be) the same as those recorded for prehistoric or early colonial times but are, instead, one part of much more interesting and dynamic cultural practices that archaeologists and other scholars should consider in their interpretations of native peoples of this region.

12.1 INTERPRETING THE PAST AND DEFINING AUTHENTICITY

While many scholars today are interested in the thoughts, practices, and interests of modern native people, one lingering issue is an underlying belief that ‘real’ Indians long ago vanished, either because native people today lack sufficient degrees of ‘Indian blood’, do not have the right phenotypical features, or do not continue traditional cultural practices. This vestige of nineteenth-century stereotypes and interpretations has continued into twentieth - and twenty-first century history-making processes and scholarship. These expectations are connected to an inability to accept that native peoples have dynamic cultures in the post-contact period, just like other groups. New England tribes were some of the first indigenous inhabitants in North America to experience colonization and pressure to assimilate or quietly ‘vanish’. By the nineteenth century, no large reservation tribes existed, as they did further west, due to two centuries of land loss (see O’Brien 1997) and a less conspicuous presence on the landscape. But this history does not mean Indian people disappeared from the area or that the material culture dated to the seventeenth century best defines their historic past. Throughout the past 10,000 years and up to the present, native tribes in this region have remained distinct through their cultural practices, even when they incorporated non-native elements. As the examples discussed below demonstrate, the authenticity of these practices cannot be contested, especially when they exist in the form of physical structures visible across the landscape.

In this chapter, I stress the importance of changing how southern New England Native American cultural practices are interpreted and used in academic translations, and of shifting power relations away from those who have long dominated these interpretations to the privileging of modern indigenous understandings of their past and these practices. Similar challenges of who controls historiography exist in Africa, Australia, and other places (Lane, Waltz, this volume). I suggest that we reconsider the concept of authenticity relative to Indians in this area, the homeland I am most familiar with as a member of the Nipmuc tribe and where my research over the past fifteen years has been focused. I present several examples of more contemporary cultural practices (i. e., not tied to prehistory) that anthropologists might not immediately consider to better understand tribal groups from this region. These practices are just as meaningful and authentic as earlier ones because of the meaning they have to the people associated with them and because they clearly connect contemporary native people to their past.

For me as a native scholar, the death of prehistory means liberation from the concept of authenticity as it has been defined by outside interpretations and creating new definitions that rely on indigenous places, structures, and cultural practices that can still be observed today, rather than only in the archaeological or historical record. Traditions of native people do change and, furthermore, must be created to begin with, as is the same with groups across the globe whose cultures we do not see as fixed in time. Understanding the origin of some of these cultural practices provides insight into the native tribes that continue to exist. Not all practices date back to some undefined moment in deep time; some ‘traditions’ that contemporary native groups in New England practise today, for example, can be traced to their creation within the past few centuries, as discussed below. Does that make them any less traditional—or authentic—than others that can be traced back further through the archaeological, historical, or oral record? Just as importantly, are the tribal groups that embrace these practices any less native because they identify with traditions that are not necessarily connected to their pre-contact past? These questions force one to consider the meaning of traditions and how they are defined and interpreted, both by those who practise them and by outsiders, a main focus of this chapter. These are important issues for archaeologists and other scholars because they influence significant social and political processes of today, as well as interpretations of authenticity. The ‘knowledge’ created and perpetuated by non-native people has dominated histories that continue to affect important decisions about land claims, federal acknowledgement (also noted by Mrozowski, this volume), and the repatriation of ancestral remains.

My investigations of the past—as well as personal experiences—have revealed a resistance to allowing native peoples to define their own cultural practices in the post-contact period. This resistance is rooted in nineteenth-century interpretations that freeze native people in time, in a world of ‘Indians and arrowheads’ visible in many historical societies, library displays, and archaeological societies throughout New England. Interpreting the past has been the task of amateur and professional archaeologists and historians, and, more recently, government officials. The Massachusetts Archaeological Society (MAS) provides one poignant example of how ‘knowledgeable’ non-native ‘experts’ have defined native culture within these narrow limitations.

The society’s goals include stimulating ‘the study of archaeology and Native American cultural history’ in Massachusetts, fostering ‘public understanding through educational programs and publications’, and promoting scientific research (MAS 2009). The society is centred at the Robbins Museum in Middleboro, Massachusetts, which holds 70,000 artefacts. On the MAS website, under ‘Education’ one could (until recently) learn about the timeline of Native Americans in southern New England, which ended at contact 400 years ago according to the website.3 Schoolchildren and educators in Massachusetts and budding archaeologists use MAS to learn about the area’s history, while at the same time forming an understanding of native people from the region. Many academics from New England have also been associated with MAS over the decades and have contributed to the interpretations presented by this organization. Through this website, viewers may well conclude that Indian tribes in the region either no longer existed after contact or have made no significant contributions in the past 400 years.

This example underscores how the dichotomy between prehistory and history has produced inaccuracies about native people that have been ingrained in the landscape of New England. One corrective for this would be a clarification that this timeline focuses on the pre-contact period, while providing links to tribal websites or a bibliography of archaeological sites that explore native history in this area since contact.4

This page (<http://www. massarchaeology. org/timeline. htm>) was under construction as of June 2011.

4 One model for this is provided by the Hassanamesit Woods project (<http://hassanamesit. org/>); see Mrozowski etal. (2006).

The lack of connection to the contemporary native tribes that still exist in Massachusetts43 unfortunately demonstrates that the practice of creating histories about Indians that define them solely as elements from the past still occurs. It also clearly speaks to the artificial divide between prehistory and history that still needs to be addressed by those who practise archaeology and are the ‘keepers’ of knowledge about New England’s past.

The continuation of racist thinking throughout the twentieth century and into the twenty-first in America (Mrozowski et al. 2000: xxii) further complicates interpretations about native people in New England, and academic scholars can be just as guilty of this type of discrimination. Anthropologists and historians often want to know if they are researching and dealing with real Indians or invented ones, which can be detected in their works.44 For example, some scholars have constructed histories of New England Indian tribes that neither conclusively confirm nor deny the continued existence of distinct tribal entities (e. g., Mandell 1996, 2008), despite the living people and physical evidence (discussed below) still on the landscape. Others have countered this by reaffirming the continued presence of ‘unseen neighbours’ (Baron et al. 1996; Boissevain 1959; Calloway 1997; Campisi 1991; Doughton 1997; Weinstein 1994). Some attempt to discuss racial and ethnicity issues and related topics such as pan-Indianism in New England from an outside perspective (e. g., McMullen 1996), while others overtly argue against authenticity (e. g., Benedict 2000). At the heart of this discourse lies the question of whether natives’ adoption of Euro-American material and cultural practices equates to a concomitant loss of tribal identity, cultural cohesiveness, and authenticity.45 The presence of those who still question the authenticity of contemporary Indians reveals that much work remains to be accomplished in this arena.

12.2 RETHINKING THE PAST AND THE CONCEPT OF AUTHENTICITY

As suggested above, the concept of authenticity, as applied to native groups, is closely connected to how much a culture’s practices are unchanged or replaced by ‘invented’ or Euro-American ones. Marshall Sahlins has noted, though, that all peoples invent traditions, including Western groups. His primary example is the Renaissance and its use of ancient Greek and Roman culture that gave birth to ‘modern civilization’ (2002: 3-4), thus allowing ‘old’ Europe to transform into the modern world. Several hundred years later, another invented Western tradition was born out of European culture: the giving holiday, now a defining element of American history and culture. Sahlins notes that ‘when Europeans invent their traditions. . . it is [considered] a genuine cultural rebirth, the beginnings of a progressive future. When other peoples do it, it is a sign of cultural decadence... of a dead past’ (2002: 4). The Renaissance, for example, is commonly seen as a transition in and heightening of (rather than a break in and loss of) European culture. This concept of transition (versus loss) is a significant issue for Indian tribes today, especially in the context of the federal acknowledgement process that demands they demonstrate their authenticity to a government agency (the Bureau of Indian Affairs, or BIA) dominated by Western ideologies that rely on the ‘expert’ opinions of non-native scholars.

To demonstrate their authenticity, southern New England tribes must connect their present-day cultural practices directly back to the period of the Pilgrims. The acknowledgement criteria require a petitioner to demonstrate their presence, community, and political activities ‘from historical times until the present’.46 Part of the knowledge base developed by outside scholars about this period comes from the myth of giving. The images and stereotypes that have continued for centuries are connected to the nostalgia surrounding the concept of ‘the First giving’, now an important and uniquely American holiday. Thoughts of New England Indians often evoke specific images, such as Indians and English people ‘breaking bread’ and sharing resources in a ‘New World’ that was harsh and inhospitable to colonizers. The iconography representing the good relations that founded this country has been immortalized in grade-school classrooms across the country every November, where teachers may refer to images such as Jean Leon Gerome Ferris’s

Fig. 12.1. The First giving 1621 by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris (Courtesy of Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Reproduction no. RLC-D416-90423). Popular images of the First giving between Indians and English settlers in New England have helped create the American invented tradition of the giving holiday that memorializes a mythic past and the founding of this country

The First giving 1621 or a similar painting by Jennie Brown-scombe from 1914 (Figs. 12.1 and 12.2). In these works, benevolent English settlers dominate imaginary scenes of the First giving, controlling the food, space, social relations, and material culture (architecture and furniture contributed to the undeveloped New World). In contrast, Indian participants occupy a subservient, seated position defined within a backdrop of an ocean dividing the civility of English culture (on the right) and the wilderness of Indians (on the left). The dichotomy between civilized colonists and wild Indians, as well as the foundational concepts of native culture as perishable and ‘without history’, is also discussed in Kehoe (this volume).

These images of the peaceful meal that gave birth to America provide just one example of how New England Indians have been documented by the standards of those around them. The depictions were part of a broader myth based on America’s history being defined by European settlement (i. e., ‘historical times’) and the country’s origins with the

Fig. 12.2. The First giving at Plymouth by Jennie A. Brownscombe (1850-1936) (Courtesy of Pilgrim Hall Museum, Plymouth, Massachusetts)

Founding of Plymouth Colony. This myth also required the eventual extinction of Indians or, if acknowledged, as assuming a subaltern role to the founding fathers, as depicted in Figs. 12.1 and 12.2. The native past was often closely connected to times of stress, flux, or uncertainty, while Pilgrims represented an unblemished purity and moral character that provided the country’s foundation (Baker 1992: 347, 350). Much like other invented traditions from the nineteenth century, Pilgrim myths and the associated giving holiday provided a concept of communal values foundational to American nationalism (Baker 1992: 348, 350-1). Any population not part of—or questioning the validity of—this myth threatens this nationalism. Through their resistance to assimilate, Indian people have posed this threat and therefore must be ‘contained’, both ideologically and politically. The hegemonic relationship represented by the giving myth continues today through scholarship and government agencies such as the BIA that seek to define native authenticity through interpretations of our culture and history.

giving images from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries relegate Indians as elements of the past, much like the MAS has. They also provide an example of what Schmidt (this volume) has referred to as ‘colonial-era fabrication’ that has involved erasure of non-Western histories, with North American historical archaeology representing one practice of reproducing colonial legacies. When these images of the First giving were created, Indian people in New England certainly no longer dressed or presented themselves this way, just as when the MAS website was created during the Digital Age, native people in the region would confirm (if asked) that their timeline did not end 400 years ago and that they no longer relied on stone tools. Within these powerful representations, the underlying message to the public accessing them is that real Indians—such as those who greeted America’s founding families—no longer exist in New England because the contemporary native people who lived during their creations are not referenced in any way. Rather, the images and concepts of their past dominate.

This ‘reality’ surrounding what constitutes an authentic Indian in New England is one shrouded in myth, mysticism, nostalgia, and erroneous concepts defined by non-native people memorializing a past and willing it to continue in the present. The work of anthropologist Frank Speck during the first half of the twentieth century provides an example of how this reality extended into academia. The prevailing myth of vanishing Indians during this period encouraged Speck and amateur historians (such as Thomas Bicknell) to search New England to identify Indians from whom they could record the vestiges of a disappearing culture. The first published academic discussion of the Nipmuc tribe was by Speck (1943) in the Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeology Society. This treatment in an archaeology publication reaffirms that the discourse of disappearing Indians in southern New England continued well into the twentieth century. Speck’s approach to anthropology developed from Franz Boas’s belief that anthropologists should record and collect everything about native people before they disappeared or changed too much, in effect treating living people like archaeological specimens and like their ancestors who were being excavated from the ground across the country by the very archaeologists reading these bulletins.

Speck’s understanding of Nipmuc culture was limited by the persistent stereotypes that still existed dictating how Indians should look and act. Speck, and others after him, based their studies on the premise that although they might still find some remnants of Indian culture, few real Indians existed in southern New England by the 1900s. He noted, for example, that while the Bird (or Briggs) Report of 1849 claimed that Indians in Massachusetts would ‘undoubtedly lose their identity and become merged in the general community...a century of time has not entirely fulfilled this prophecy’ (1943: 51; emphasis added). This statement suggests to Speck’s audience that a majority of the native population had lost their identity, and that his study of this remnant population was an important contribution because he was capturing information about a vanishing race. In a description that would be echoed decades later (e. g., Mandell 1996, 2008), Speck referred to the remaining Indians as ‘small groups of tribal descendants forming ethnic islands’ (1943: 49). Further confirming the anticipated demise of Nipmuc culture, he noted that ‘whatever remains to be learned must come by word of mouth from older members of these social denominations before they pass into the shades’ (1943: 49), or shadows.

A reliance on ethnic identifiers and stereotypes is also apparent in Speck’s work, which the BIA uses as a primary source for assessing federal acknowledgement cases. Although he did not subscribe to the biological concept of race—and, in fact, acknowledged that this was a ‘now obsolete term’ (1943: 51)—Speck struggled with racial and ethnic identifiers, just as the nineteenth-century historians before him did.47 For example, he noted that

The characteristic of curly hair... has caused most recent writers...to reproduce the lop-sided rubric of ‘race classification’ and call them ‘colored’; whence ‘negro’. This will not pass challenge in all cases, [perhaps because] in some Indian families, as well as individuals of no more than one-eighth negroid ancestry, the hair is less curly than in others of three-quarters white origin. (1943: 52)

Speck’s focus on hair curl provides a brief yet satisfying clarification of native racial identity for him. It also demonstrates that the issue of Indians mixing with other ‘races’ was still an important consideration for non-natives in the twentieth century as they struggled to define Indians, Indian culture, concepts of biological race, and authenticity.

My experiences in the world of academia have further demonstrated that biology, stereotypes, and misperceptions about Indian authenticity continue to exist. Recently, a colleague was shocked to learn that I have native heritage because she had summed me up by my biological features and her belief that Indians do not really exist in southern New England any longer. Simply put, I did not look Indian to her, nor do the other tribal peoples in the region who have dark skin, light skin, curly hair, or blue eyes. Intermarriage with non-native peoples has erased our blood, according to this assessment of authenticity. Another professor taught courses on Native American culture and history, yet confessed privately that there were not—could not be—any real Indians in New England today. Like so many before him, he was stuck in a past that defined native people as culturally static and only authentic if they looked and acted like images in books. His definition negated our continued presence in the contemporary world and did not demonstrate any understanding that the contemporary cultural practices of Indian people in New England connect dynamic, living groups to their pasts in complex ways. For the remainder of this chapter, I address this issue and share more recent (i. e., the past two centuries) cultural practices that are not commonly discussed in academic translations of Indian culture from this region.

12.3 CULTURAL PRACTICES AND RELIGIOUS BELIEFS: EXAMPLES FROM SOUTHERN NEW ENGLAND

These experiences and interactions with voices from both past and present have prompted me—as an archaeologist, ethnohistorian, educator, and tribal member—to reflect on the meaning of contemporary native cultural practices in southern New England and their significance to understandings of authenticity. Although many cultural practices that have changed over time could be discussed, I focus on a select few here. The first is the annual Nikkomo celebration held in December by tribes in the region. The second practice focuses on the centrality of Christian churches to several groups as important components of cultural landscapes, memory, history, and culture.

12.3.1 The Nikkomo Celebration and Accommodating Christianity

The modern Nikkomo celebration is a gathering of tribal people and friends during the Christmas season. Many modern-day native people in southern New England are also Christian and celebrate Christmas in addition to attending tribal events, such as powwows, Strawberry Moon festivals, homecomings, and Nikkomo. This annual gathering allows tribal people to gather during the winter, similarly to how many extended families do during the holiday season. Nikkomo provides an example of how cultural change—in this case, religious beliefs and practices—can be construed as recurrence and a revising of the past by people over time. Through gatherings such as Nikkomo, each generation that has kept this practice alive has revised it to accommodate their own experiences and realities (Simmons 1986: vii, 267) while maintaining a connection to the event’s origin.

As with other areas across North America, over the centuries an ‘ebb and flow of Indian and non-Indian elements’ (Simmons 1986: 266) intermixed with native religious beliefs in southern New England. This ebb and flow corresponded with the political history of the area as external forces impacted the rate of change and activities related to Indian tribes. The underpinning of native societies from earliest contact due to epidemic diseases and intense population loss, combined with political and military domination, led to a mixture of old and new and cultural borrowing in native culture in this region since the 1600s. Over time, selections were made regarding which non-native elements to integrate, while other changes occurred independent of native choice (i. e., were imposed). Modern Nikkomo represents one result of this.

The adoption of Christianity may be seen as either of these (an independent choice or one imposed on native groups). One important role of this transition was the basis for group identity in a changing world; adoption of Christianity sometimes contributed to group cohesion despite its difference from traditional native religions. Christianity, in fact, could be seen as a reconstructed form of native beliefs and examples exist to support this. Some converted Indians believed that their pre-contact ancestors had also known the Christian religion; their motifs and legends accounted for new experiences but, at the same time, combined old and new symbols in reconstructed narratives (Simmons 1986: 261-2, 268).

The struggles of Indian people in southern New England over the centuries mediating their beliefs between native belief systems and Christianity were recorded in some forms into the twentieth century. One example is the Wampanoag story about Patience Gashum, an Indian herbalist who encountered the devil on her deathbed. In this recounting, native herbalism is described as ‘the black art’ (Simmons 1986: 93; compare Vanderhoop 1904), suggesting that during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries some tribal people were still mediating these different belief systems. Still, they clearly remembered the important role of herbalists in their culture.

This mediation also existed in earlier centuries, providing further evidence of connections between past and present. Newly converted tribal people from southern New England in the mid-1700s reportedly evoked dreams and visions as responsible for their conversion, rather than the Bible. One Narragansett elder spoke of dreams involving images of God, Jesus, and ancestors, clearly a mixture of native practices with Christian iconography. And Indian preachers and narrators, often leaders in other areas besides religion, wove elements of English and Indian traditions into their Christian legends. More recent examples (i. e., from the late twentieth century) include a medicine man or woman as a central figure in tribal affairs and references to ‘God’ as the ‘Great Spirit’ or ‘Manitou (Simmons 1986: 90, 249).

The opening prayer of the Nikkomo gathering for the Nipmuc Nation, for example, often references ‘Lord’, the ‘Great Spirit’, and the ‘Creator’. These are appropriate references because many tribal members practise a combination of Christian and native religions, as noted above. The event includes giveaways (door and raffle prizes)—also common at other southern New England tribal gatherings such as the Mohegan Winter Social—and drumming, while the pot-luck offers a mixture of very American foods: fried chicken, macaroni salad, sandwiches, a bean dip, and various cakes, cookies, and pies. Not a single dish of succotash, venison stew, Johnny cake, or cornbread was part of the event last year, yet this gathering was just as tribal as our annual powwow, where those dishes are usually available, in addition to hamburgers, hot dogs, and soft drinks. Other tribes in the region also celebrate Nikkomo, as noted above, an event dating back generations that marks the first moon of winter. For the Narragansett tribe of Rhode Island, the modern Nikkomo functions as a giveaway and attendees bring gifts for others in need. These gifts are distributed through the tribe’s Social Services Department. A holiday market, traditional foods, and flute music complete their holiday event (Tomaquag Memorial Museum 2010).

Contemporary Nikkomo celebrations are as significant to southern New England native cultural practices as more traditional ones that tend to be more obvious (e. g., wearing regalia at powwows or the wetu constructed on our reservation in Grafton, Massachusetts, for sweat lodges). Significance lies not in the outward appearances or food that is served but in what the people involved consider important: the social relations maintained through these practices. These cultural practices are enacted and continued by tribal members who determine how they will be configured, what their meanings are in the present and have been in the past, and, when appropriate, how they should change, though this often occurs unconsciously. Sometimes, archaeologists working in the Americas fail to recall that the past they uncover is directly linked by individual generations to people alive today and their cultural practices. Each generation transformed traditions such as Nikkomo, just as they did the more obvious material culture items that the study of the past is based on.

Much like the Nikkomo celebration, native Christian churches represent a history of accommodation, blended beliefs, and transformed cultural practices by southern New England tribes. They are perhaps more clearly connected to changes that have occurred over the centuries. These places, like the gatherings that occur in and around them, have histories associated with the structures that are integral to the cultural practices of their tribal groups. Outsiders also clearly associate them with tribal entities and, often, family and tribal identities become enmeshed with the biographies of these cultural landscapes.

Central to the stories of these places is the common theme of land loss. Standing structures such as Indian churches assumed increased meaning following land loss of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries; this land loss culminated in individual allotments in the 1800s designed to terminate communal land holdings and accelerate assimilation (Simmons 1986: 264). For outsiders, these structures became the physical reminders of the continued presence of native people in the region. For tribal people, the remembrance of and connection to the land continued over generations through individual accounts of how the land was used, where ancestors were buried, and origin myths, among other things. The common feeling of loss to whites is evident in stories recounted in the later twentieth century. For example, Narragansett historian Ella (Wilcox) Seketau shared with William Simmons (1986: 171) a story of buried gold once seen from afar by her ancestors that was later discovered by land developers, who then divided up the money. Such stories that equate land with treasures emphasize the fate of native people at the hands of non-natives who have invaded their homelands and profited from their sale, use, and development. Many of these stories first appeared in the early twentieth century, following a long period of intense dispossession.

Today structures such as the Mohegan Church in Uncasville, Connecticut, the Old Indian Meeting House in Mashpee, Massachusetts, and the Narragansett Indian Church in Charleston, Rhode Island, provide links to the past that the land of southern New England once did. They are only three examples of many that demonstrate how the landscape is still used by native people in this region to maintain the important connection to place. These public, monumental-style buildings exist on tribal lands that have dwindled;48 other tribes, such as the Mashantucket Pequot, Eastern Pequot, and Schaghticoke that retained larger areas of land in the form of state reservations, did not construct such visible reminders.

For archaeologists, these structures can serve as artefacts providing insight into the past and, more importantly, connect the living people of today who use them to this past. They play similar roles to the Swahili chronicles in providing alternative views and new perspectives of the past (Pawlowicz and LaViolette, this volume), like the way oral accounts record a type of narrative not immediately apparent to those looking to the past for a deeper understanding of the present. Both represent a different understanding of time as connected to place. Although these churches are historical in that they were erected in the post-contact period, they connect tribal people to a much deeper past. Much like the chronicles, these structures help one move beyond the history/pre-history dichotomy that has shaped interpretations of the past and challenge the dominant narratives about southern New England. The meaning of these places is also embedded in the indigenous historical knowledge maintained by tribes, the type of ‘history in sites’ only revealed by exchange with tribal people (Hantman, this volume).

12.3.2 The Mohegan Church

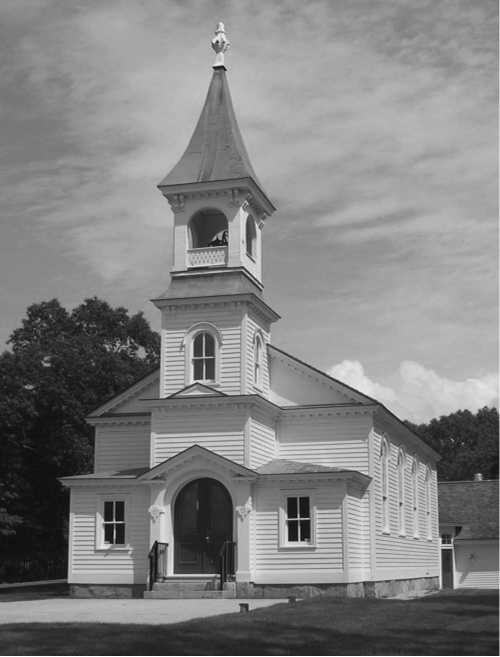

A white, spired Congregational church with Italianate details marks a plot of land that has been central to the maintenance of Mohegan tribal identity and continued presence in southeastern Connecticut for nearly 200 years (Fig. 12.3). Also mixed into the cultural practices of this tribal group are Christian elements, as this building makes evident. The history of this tribe includes an alliance with English settlers since contact. Despite good relations with their English neighbours, the Mohegan resisted religious conversion longer than other groups such as the Nip-muc and Wampanoag, accepting Christianity in the 1740s during the Great Awakening (Simmons 1986: 83,259). This was 100 years later than the Massachusetts Indians influenced by missionaries such as John Eliot (among the Nipmuc) and Richard Bourne (with the Wampanoag).

This structure reveals the mixture of native and Christian elements that permeated Indian culture in the region; this mixture is also evident in other Mohegan cultural practices. Fidelia Fielding (1827-1908), for example, spoke and wrote in the Mohegan language in a diary that was preserved and studied by Frank Speck. Within this diary are elements of Mohegan and Christian thought used by later generations, including her grandniece Gladys Tantaquidgeon (1899-2005), to preserve Mohegan language and customs that continued through Fielding’s memories and experiences (Mohegan Tribe 2010; Simmons 1986: 82). Ironically, through the English-introduced practice of writing, this native language was preserved. The church served much the same purpose. Although very English in its outward appearance, within and around it cultural

Fig. 12.3. The Mohegan Congregational Church in Uncasville, Connecticut (<http://historicbuildingsct. com/?p=5090>)

Practices occurred that preserved Mohegan culture through the twentieth century and into the twenty-first.

According to the tribe, the Mohegan Church helped it maintain a presence in the area in addition to providing a place for regular religious and socio-cultural gatherings. The land beneath the church is one of only a few places that have been continuously owned by the Mohegan people since before colonization (Mohegan Tribe 2010). Throughout the twentieth century, the annual Mohegan Wigwam Festival was held here and served as a central gathering for tribal members, while also including other Indians from the region. A women’s sewing circle was another activity that occurred here, and it was instrumental in helping the tribe prove its authenticity to the BIA during the federal acknowledgment process (US Dept. of the Interior 1994). Today, the church includes an exhibit of items the tribe considers important to its history, while it continues to function as a gathering place for educational and social activities and remains central to Mohegan identity (Mohegan Tribe 2010). The location of the church is also an identity marker; it is known as ‘Mohegan Hill’.

The BIA recognized the Mohegan Church as central to tribal continuity in its federal acknowledgement determination.49 Their analyses also persistently looked for the maintenance of traditional activities and cultural ‘values’. In the Mohegan final determination, for example, the BIA noted that ‘John Tantaquidgeon strongly maintained Mohegan cultural traditions, such as basket-making and wood-carving’ (US Dept. of the Interior 1994: 47). This example demonstrates how the federal acknowledgement process reinforces that modern-day Indian people must continue cultural practices of the past to be considered authentic today. If tribal people fail to continue crafts and practices such as basketweaving, wood-carving, making and wearing regalia, or speaking their language, are they no longer Indian? By whose definition and criteria? These are the very issues that legal processes such as federal acknowledgement and land claims cases address (such as the Mashpee case; see Campisi 1991).

One positive result of these public discussions about tribal identity and continuity is that tribal voices inherently become part of the record. We learn from the Mohegan federal acknowledgement case about the meaning of Mohegan Hill and the church from tribal people who have their own definitions and insight that could not be gained from outside experts. Events and activities that occurred here included the Mohegan Ladies Sewing Society, noted above, which sponsored an annual Wigwam Festival that served as a fundraiser for the church as well as a much anticipated tribal social event (US Dept. of the Interior 1994: 61). One tribal member recalled the camaraderie and interactions surrounding this event: ‘The morning after the wigwam we all gathered at the Church kitchen for Community breakfast. It was the custom to clean up the leftovers. Bokie would make a kettle of coffee’ (US Dept. of the Interior 1994: 62).

Other ‘small, ongoing daily connections of people’ (US Dept. of the Interior 1994: 68) occurred as a result of the continued presence of the church on Mohegan Hill. Political and social news were shared here, and tribal members gathered to perform maintenance and restoration tasks on the building (US Dept. of the Interior 1994: 68-72). Beyond these, community memories trace their personal identities back to this central place. Tribal leader Courtland Fowler (1905-91), for example, initiated restoration of the church in the 1950s and recalled his personal connections: ‘My wife and I attended this church for many years and my father, Edwin E. Fowler, the oldest male descendant of the Mohegans living.. .was the sexton for many years’ (US Dept. of the Interior 1994: 73). By invoking the image of a tribal elder and descendant of the Mohe-gan, Fowler’s connection to the Mohegan Church extended back in time to the ancestors connected to this place for millennia. He understood that on many levels, this building and the land under it symbolized what made Mohegan unique from their non-native neighbours. Perhaps most importantly, the very name of the tribe has been preserved in the structure, the Mohegan Congregational Church, as it has with Mohegan Hill.

Tribal members recognize that their strong presence today is in part due to the continuity they have maintained with the land and their ancestors—many of whom are buried close to Mohegan Hill at Shantok or nearby in Norwich, Connecticut—going back into prehistory. Yet, the modern-day Mohegan are often considered much less interesting than their past to archaeologists who study the cultural artefacts that (to them) have defined Mohegan cultural practices. Like Frank Speck, these academics see their primary goal as recording the disappearing or lost traits of native cultures and have difficultly connecting that past to the present in their definitions of what authentic Indian culture is.

12.3.3 The Mashpee Old Indian Meeting House

The second example of a structure that connects a present-day southern New England tribe to its past through the cultural practices associated with it is the Mashpee Old Indian Meeting House (Fig. 12.4). Originally constructed in 1684 in Mashpee, Massachusetts, this building is considered to be the oldest extant Indian church in the country (Community Preservation Act Committee 2010). The meeting house, like the other examples in this chapter, represents centuries of accommodating Christianity for the natives associated with it. The development ofMashpee in the post-contact period is closely connected to the presence of Richard Bourne (1610-82). Bourne was one of several early Cape Cod settlers

Fig. 12.4 Mashpee Old Indian Meeting House in Mashpee, Massachusetts (courtesy of the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribal Archive)

Whose goal was to bring Christianity to the Wampanoag, following the example of Puritan missionary John Elliot and his work with Massachusetts and Nipmuc Indians (Gould 2005; Simmons 1986: 18).

In the 1600s, the concept of ‘place’ in the Massachusetts colony became inextricably tied to the English need for plantations where Indians could be gathered, preached to, and, ultimately, controlled.50 Although in theory governed by Indian ‘proprietors’, these settlements expected residents to embrace English religion, reading, and writing in pursuit of earning ‘recognition as a township of Christian Indian freemen’ (Simmons 1986:18). The Mashpee enjoyed a degree of local autonomy as proprietors of their plantation lands, but less than isolated groups such as the Aquinnah on Martha’s Vineyard (Simmons 1986: 258).

Another important component of these colonial plantations was the ‘exchange’ of large areas of land for the town-like Indian settlement. For example, in 1665 Bourne convinced leaders of the Mashpee area (known then as the South Sea Indians) to allocate 25 mi2 for their collectively owned plantation (Simmons 1986: 18). This ‘exchange’, however, meant that the surrounding land was not collectively ‘owned’ by the native inhabitants any longer, making way for English settlement in this coveted coastal area. State-appointed guardians were central to this transition; their role was to manage the land holdings and financial affairs of their Indian wards. Despite several centuries of being under this type of ‘management’, the Mashpee regained much of their autonomy by the nineteenth century. But late nineteenth-century allotments (noted above) resulted in more land loss, increased integration of non-natives to Mashpee, and eventually relinquishing government of the town (Simmons 1986: 18-22). Tension between native and non-native occupants in Mashpee continued into the twentieth century, with the most well-documented example being the famous land claims case of 1977 (Cam-pisi 1991).

The Old Indian Meeting House is in some ways a reminder of 400 years of accommodating missionaries such as Bourne, state-imposed guardians, and loss of land and management of their township; yet it is also a beacon of how persistent Mashpee people and culture have been. Today, it serves as a space for tribal gatherings and as a mnemonic device to recall the strength of Mashpee people who used, maintained, and recently restored the building over the generations. For example, at tribal gatherings, such as the funeral of tribal leader Russell Peters in 2002, the Meeting House becomes a place to reflect on tribal life, gather in remembrance of those who have passed away, and continue solidarity into the future. Important socio-political people and movements of the past are also connected to the Meeting House. The influential Pequot preacher William Apess lived at Mashpee in 1833 and was instrumental in the Mashpee Revolt against state authorities that year (Calloway 1999: 230). During this peaceful movement, tribal members specifically addressed the intended use and purpose of the Meeting House in a notice to state officials. Recalling this issue, Apess said (1835: 17), ‘We also proceeded to discharge the missionary, telling him that he and the white people had occupied our meeting house long enough and that we now wanted it for our own use.’

These activities around this structure, both from the past and present, demonstrate how the Mashpee have maintained influence within their homeland, despite four centuries of change and accommodation. Like the Mohegan—or any other living culture—Mashpee culture is dynamic; these transitions should be viewed as successful adaptations to the changing world of the past, rather than a failure by Indian people to remain traditional. Continued use of the Old Indian Meeting House confirms that this tribe’s connection to land and place has persisted for generations up to the present, although use of the building has changed over time. In 1684, it represented an imposed religion by English settlers and the resultant hegemonic relationships between Indians and non-Indians of the Cape Cod area. Over time, however, the Meeting House transformed from being a symbol of English domination over native cultural practices to a place where political sovereignty and social cohesion were maintained despite English domination of the area. Eventually, this sovereignty was confirmed by outsiders, resulting in the 2007 recognition by the BIA of the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe.

12.3.4 The Narragansett Indian Church

While the Narragansett Tribe of Rhode Island did not form an alliance with a formal missionary, it did accept the presence of Roger Williams (c.1603-83), whose goal was similar to Bourne’s and other seventeenth-century missionaries: to both Anglicize and Christianize this group. Following King Philip’s War of the 1670s, land became a divisive issue for the Narragansett, as some favoured selling land to English settlers but a large portion of the tribe did not (Simmons 1986: 260). Tribal presence, identity, and internal politics were often defined vis-a-vis such outside forces since colonial times, as with many other tribes. Like the Mohegan Church and Mashpee Meeting House, the Narragansett Indian Church is central to that tribe’s history and how they interpret their traditional past. The Annual August Meeting and Green Corn giving (the tribal powwow) is held on tribal grounds surrounding the church, originally constructed in the mid eighteenth century during the Great Awakening when they recognized Christianity. Over the past 250 years, the church and land around it have been central to the tribe’s continued presence as they were the only physical elements to have been continuously occupied by the group (Harvard University 2009).

Following the 1880 ‘detribalization’ of the Narragansett by the state of Rhode Island and the sale of over 920 acres, the tribe retained only 2 acres surrounding the church (US Dept. of the Interior 1982: 4, 1983). Similarly to the Mohegan situation, the Narragansett Church and its grounds became a centre point of community organization and solidarity in the early decades of the twentieth century. Although technically a separate organizational structure from the tribal leadership since 1934 (US Dept. of the Interior 1983), the church has maintained a prominent role in tribal social and political activities. At times, the church provided the only tribal institution recognized by the state, and two of the tribe’s political leaders (Daniel Sekater and John Noka) also served as reverend and deacon at the church; during other periods, the church board and tribal leadership were also often composed of the same people or overlapped considerably. The powwow held each year on church grounds has been a cooperative event between the tribal council and church leadership. The church has also sponsored youth and elderly activities in the past, as well as holiday celebrations. Although most of these events are now housed at the tribe’s nearby community centre, church services have been an important component to the annual August Meeting, when many tribal members attend as part of the weekend-long event (US Dept. of the Interior 1982: 4-6, 10, 13).

Many could look back at the history of the Narragansett Tribe and point to the Indian Church as perhaps the most critical element of its past that helped this group maintain a presence in southern New England, similarly to the role of the Mohegan Congregational Church. Other cultural practices have persisted for this group because a core was maintained—physically, politically, and culturally—at this place. Furthermore, the materiality of the Indian Church (see Fig. 12.5) is a reminder of the continuing practices of a people closely connected to their land.

Fig. 12.5. The Narragansett Indian Church in Charleston, Rhode Island (<http:// En. wikipedia. org/wiki/File:NarragansettIndianChurch. jpg>)

Within the Narragansett community, stonemasonry has been an art handed down for generations, with several families recognized by Indians and non-Indians in the southern New England region as skilled stone workers with distinctive styles. My father, for example, was trained by members of the Narragansett Wilcox family in this trade and was a highly sought-after craftsman because of the uniqueness of their stonework. While the other churches discussed in this chapter were constructed from wood and have more European exteriors, the Narragansett Indian Church uniquely connects its members to their past through its materiality and the purposeful decision to create this building out of stone, creating the type of connections between the recent and deep pasts also discussed in Mrosowski (this volume). Similar uses of material culture from the past in contemporary practices have been documented (Lane, Schmidt, Walz, this volume).

All three churches discussed above, although clearly associated with the Christian influences that have infiltrated Indian culture in southern New England over the past four centuries, are important places of history because of the complex layers of meaning attached to the actions and events that occur in and around them (Tilley 1994: 27). Their meanings and interpretations are best defined by the tribal groups that have used, managed, created, and transformed these structures and the cultural practices associated with them; these interpretations often challenge the dominant social order. They provide a connection to and understanding of space and place that can only come from generations of presence and use, and embody the type of memory and history often associated with places of pilgrimage (Aguilar and Preucel, this volume).

The Narragansett Indian Church perhaps displays this best in its departure from the more European-style construction of the Mohegan Congregational Church and Mashpee Old Indian Meeting House. Despite the modifications these buildings have undergone over the centuries, they remain as Indian places on the landscape tribal people can return to for generations to confirm their identity, history, and cultural practices. These three churches, like the Nikkomo celebration, have weathered time and morphed over the years with the dynamic cultures associated with them. They are not places outsiders, such as archaeologists and other scholars, would normally look to for understanding native history and culture, though. Instead, they would attend a powwow or other event that more overtly presents authentic native heritage through the practices of dance, dress, and food, clearly signalling Indian to visitors. If understood in the context I have offered, these structures provide insight into the contemporary world of these native groups and clear connections between the present and past, while at the same time conveying that the history, culture, and authenticity of tribal groups in southern New England are both complex and dynamic.

12.4 CONCLUSION

In addition to representing changed cultural practices, a history of accommodation, and blended belief systems, the structures discussed in this chapter symbolize connections to a precolonial presence for these Indian tribes. They are a continuation, in more modern forms, of the practice of memory markers seen all over the southern New England landscape, often in the form of stone or brush piles to remember a person or particular event (Simmons 1986: 251).51 Both the more ancient forms and these churches are places where tribal people can physically touch their past and reconfirm their identity in the present moment. They also serve as reminders that native people continued to maintain a presence in the region throughout the historic period, including the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, partly because of the maintenance of important cultural landscapes. Without these, the trajectory of these tribal groups and their cultural practices over the past 400 years may well have been quite different.

These practices might be distinctly different from pre-contact traditional religious and social customs that are often the focus of archaeologists and others attempting to interpret the past. They remind us that tribal groups in southern New England cannot be ‘freeze dried’, as they too often have been by museums, artists, and government agencies, as discussed above, but are, in their modern state, more hybrid in their make-up (see Mrozowski, this volume) after four centuries of contact, colonization, and modernization.

Scholars and politicians have often acted as if native history ended with the arrival of Europeans and have lost sight of the very real and interesting cultural practices that exist today and offer insight into these dynamic tribal groups. More importantly, this focus has resulted in the perpetuation of a myth of erasure, with substantial impacts on land ownership over time and issues of sovereignty, identity, and authenticity. The reality is, as I have discussed, that transformations over the past 400 years have helped tribes withstand disintegrative pressures as they have both retreated and thrived at different periods in response to specific historical conditions (Simmons 1986: 258). Changed cultural practices are not indications of inauthenticity to native people; they are symbols of survival.

Over the years of working for my tribe and more recently as a native scholar, I have found myself drawn into a past that I see as still largely misunderstood, misrepresented, and, more importantly, consistently appropriated by others. The examples shared here demonstrate that the contemporary cultural practices of southern New England tribal groups should be considered as authentic as earlier contact and prehistoric practices because they are used and created by native people; they are integral to their contemporary cultures and, most importantly, how they define themselves as Indian people. We know different ways exist for viewing, interpreting, and creating histories and culture (e. g., Schmidt and Patterson 1995b). Yet, archaeologists and other scholars still often confine their understandings of native traditions to a past that no longer defines who we are today. Native people no longer live in a world of Indians and arrowheads but are active participants in a fast-paced world that, ironically, embraces change for everyone else.

World History

World History

![The Battle of Britain [History of the Second World War 9]](https://www.worldhistory.biz/uploads/posts/2015-05/1432582012_1425485761_part-9.jpeg)