The visitor to an archaeological site in Peru might get a sense of the scale and ecological context of the great platform structures, but can easily get the impression that these buildings were volumetric hulks in the landscape. The frequent use of the word “mound” to describe these buildings derives from the obvious fact that they are largely archaeological ruins. These buildings are, however, not mounds. Their purpose was to produce elevation. Furthermore, platforms have vertical surfaces and these surfaces were from the beginning an integral part of the structure’s deflnition.

Just as we look at the white stones of the Parthenon in Athens and have to recall that they were once painted in various colors, so too were these structures. A Hindu temple might be a living example of how buildings were painted. In Peru, the exteriors were colored in shades of red, the ancient color of ritual and death, but over time, the color palette became more complex and was used to portray animals, people, and mythological scenes. At Garagay, dating to 1500 BCE, there are three large terraced structures arranged in a U in the central building of which one flnds a room decorated with elaborate reliefs in clay that represent anthropomorphic and zoomorphic beings. Five colors were used: red, pink, gray-blue, purple, and yellow. One flgure

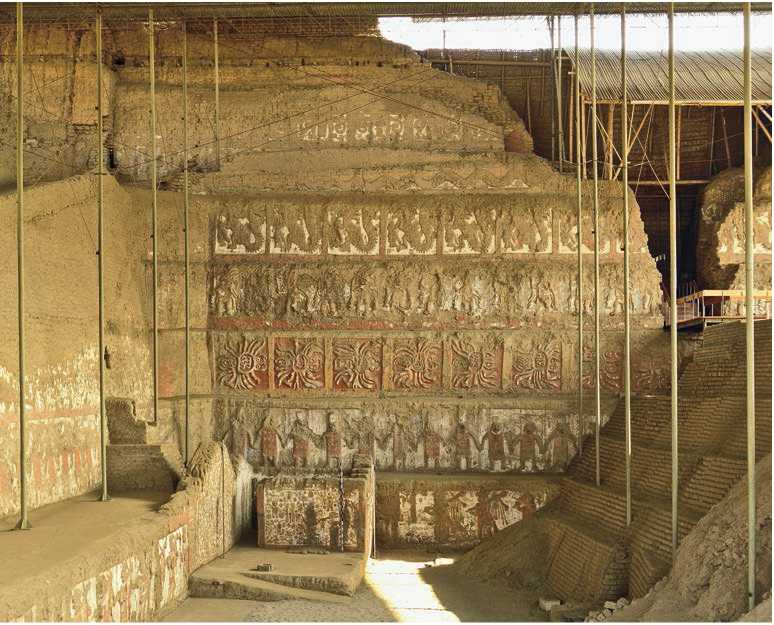

Figure 11.28: Huaca de la Luna excavation, La Libertad, Peru. Source: © S23678 (Http://cre-ativecommons. org/licenses/by/3.0/ deed. en)

Figure 11.27: Huaca de la Luna excavation, La Libertad, Peru. Source: © S23678 (Http://cre-ativecommons. org/licenses/by/3.0/ deed. en)

Shows a fanged creature with smoke coming out of his nose. He has a greenish face, a yellow collar, and is set against a red background.

Although Garagay images are the earliest known examples of such large friezes, it is clear that there must have been earlier precedents.

Carro Sechin, a one-story temple—and possibly temple warehouse—was extensively painted on the interior with figures in white, red, brick red, gray, blue-black, yellow, reddish brown, and orange-yellow. A monumental retaining wall, roughly 4.15 meters tall and containing nearly 400 granite sculptures, was added late in the site’s history and encircled the perimeter of the building. The stone sculptures depict a possible mythological or historical scene in which a procession of armed men, probably important personages or warriors, make their way among the mutilated remains of human victims (Figures 11.27 and 11.28).

Once these friezes are excavated and exposed to air and moisture they deteriorate rapidly. The vibrant colors on the walls of El Paraiso have now all but vanished. The relative paucity of surviving examples leaves the buildings mute and deprives researchers of critical evidence in understanding what these buildings meant and how they were used. This means that in our mind’s eye, we have to envision structures that are not only purposefully eye-catching, but also the site of vivid narrations. In the valleys below the buildings one has to imagine the verdant fields etched with irrigation canals and garden plots. Above the building were the monotone yellowish mountains gauged by deep shadows between the peaks against which the vibrant colors of the platforms would have made a striking impression. 26

World History

World History