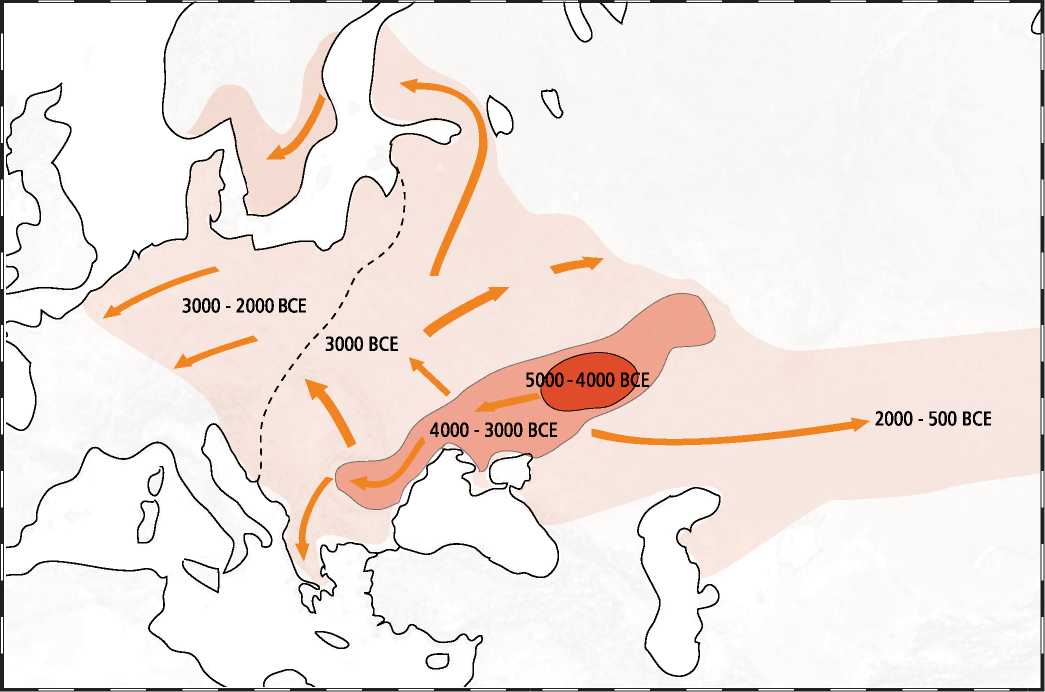

Around 4500 bce, the nomadic herders of the open steppe developed an earthwork, mortuary architecture in the form of artificial mounds, known as kurgans. They were built near a pasture and a water source, and on an elevated spot. A shallow, wide circular ditch was made with the soil placed on the inner side of the ditch. Then ceremonies were performed, after which the grave pit was dug at the center of the circle and lined with wood. The deceased were buried in this chamber along with ceremonial belts, animal tooth necklaces, copper pendants, as well as copper spiral arm rings and finger rings. When the burial was over, it was covered with brushwood and filled with soil and the whole then covered with topsoil blocks.17 In one kurgan area, at Khvalynsk on the Volga River (dating to 4500 bce), archaeologists found 158 human graves with the bones of 52 sacrificed sheep, 23 cattle, and 11 horses.18 Ritual events took place in all phases of the funerals, as is clear from where offerings were found by archaeologists: on the grave floor, in the grave fill, at the edge of the grave, and above the graves (Figure 10.16).

Figure 10.16: Expansion of Kurgans into Europe. Source: Florence Guiraud

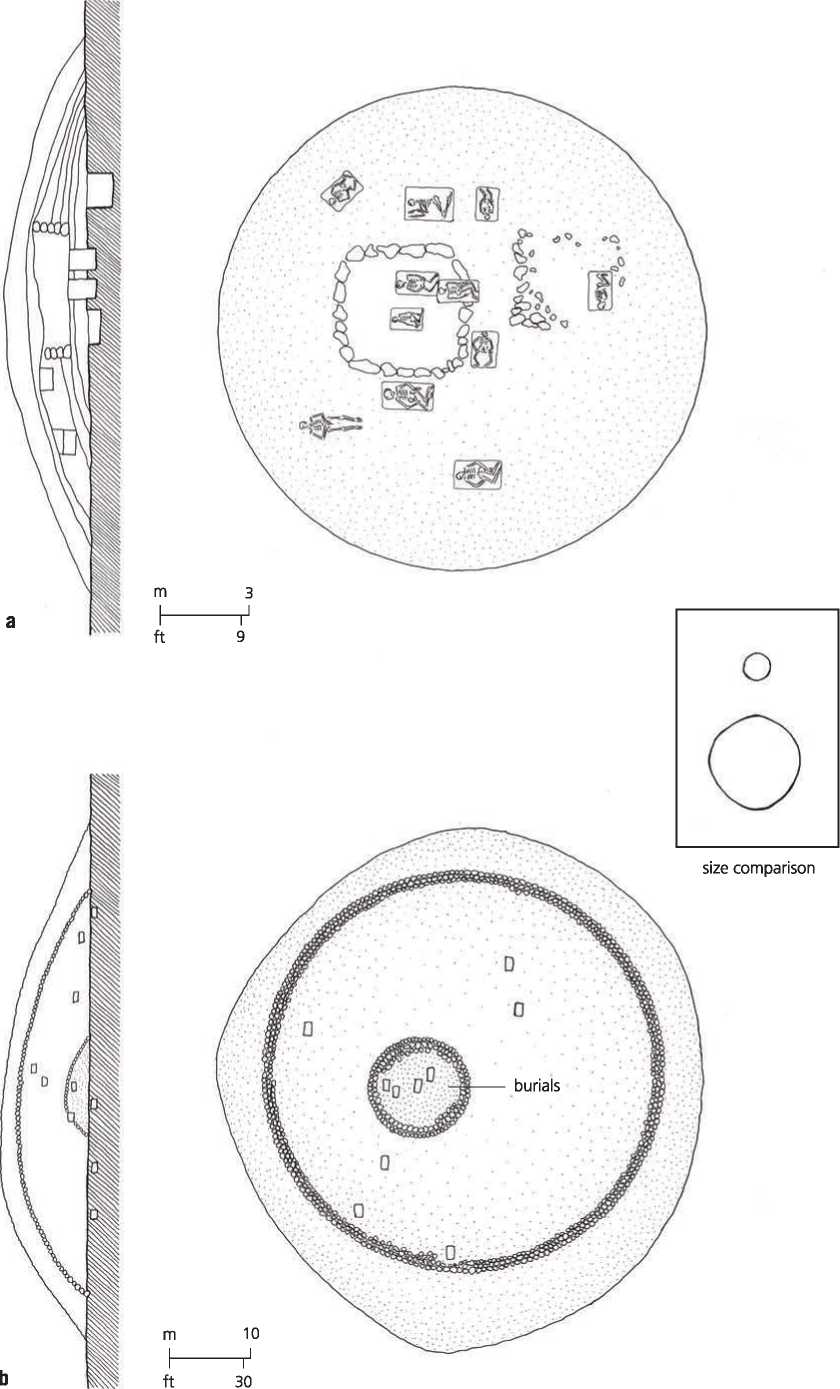

The kurgan ideology moved eastward in several waves, the first being to the rich farming cultures of the Black Sea19 (Figure 10.17a, 10.17b). Whether this was an invasion or a process of cultural integration is not known. It was probably the latter, since the development of the horse as an instrument of war was still a thousand or so years in the future. At any rate, the impact of the kurgan ideology is obvious and lies in the spread of the telltale graves that appear in Moldavia, southern Romania, and east Hungary around 4400 bce. The mostly male graves are a distinct contrast to the even ratio of male-female burials of the earlier cultures. Fortifications began to be built around the towns consisting of earthen walls, stockades, and moats.20 This period coincides with the development of new metallurgical techniques characterized by the making of bronzes of copper and arsenic and tin that replaced the pure copper metallurgy of the pervious period.21

Tens of thousands of kurgans were eventually made, especially during the next two thousand years, but few survive in their original landscape, as most have been sacrificed in the name of agriculture or archaeology. One of the more remarkable ones, the Haga Kurgan (Hagahogen) or King Bjorn’s Mound in Sweden—60 kilometers north of Stockholm—still gives a sense of the importance of the setting. It is 7 meters high and 45 meters across and it was constructed around 1000 bce at the top of an oval hill in the middle of what was once a marshy river bottom. During the burial there had probably been human sacrifice, the evidence for which is human bones from which the marrow was removed. The coffin contained a sword, brooches, a number of gilded buttons, and various other bronze objects.

For a while the kurgan builders and the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture overlapped, but the latter began to noticeably decline around 3300 bce. The reasons are not clear, but it coincided with a cooling in the climate. We see in this area the emergence of a new cultural horizon, the so-called Globular Amphorae culture, coming in from the north as well as a shift: in the eastern steppe from cattle-raising to horse-raising. It was a transformation that was to have a huge significance in the history of civilization, and will be discussed in a subsequent chapter.

Figure 10.17a, b: Two examples of kurgans: (a) Tsareva Mogila, near Kherson, Ukraine, (b) Tarvana, near Vracs, Bulgaria. Source: Andrew Ferentinos/Timothy Cooke/Marija Gimbutas, The Civilization of the Goddess: The World of Old Europe (San Francisco: HarperCollins, 1991), 366, 367

World History

World History