Perhaps the most important finding so far realized from the study of palaeopathological conditions concerns the effect the environment - natural and humanly created - has on human health. Contrary to the perceived notion that people made progress toward civilization because of the benefits of a settled, village or urban, lifestyle, palaeopathological studies have demonstrated that this process exposes people to a host of diseases that are not present in their hunter-gatherer forebears. It is with the origin of agriculture and with the advent of more highly agglomerated populations in villages and urban centers that the first signs of density-dependent diseases - crowd diseases - are found. They spread by airborne infection from exhaled phlegm or sputum, other bodily excreta, or contaminated food or goods and not only include some of the biggest killers in history, such as cholera (Figure 1), influenza, and plague (Figure 1), which leave no macroscopically discernible bone lesions, but also those that do leave osseous manifestations, including, importantly, the mycobacterial diseases, leprosy and tuberculosis.

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis, a major killer in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, remains a public health concern worldwide today. Tuberculosis is considered a disease of poverty because it thrives in situations of social deprivation. The tuberculous bacterium has many forms, including those that affect humans (M. tuberculosis) and cattle (M. bovis), both of which influence human populations, the former through human-to-human pulmonary transmission and the latter from this form of transmission and also from the ingestion of contaminated milk or meat that produces a gastrointestinal form of the disease. Both forms may affect the skeleton, producing characteristic lesions in the form of vertebral body collapse and kyphosis (Figure 8), new bone deposition on the visceral surface of ribs (Figure 9), and destruction of joints in the body, most often those of the lower limb. The gastrointestinal form of the disease is most often diagnosed from pelvic lesions, of the sacrum (Figure 10) and ossa coxae.

Palaeopathological study has had perhaps its greatest impact on elucidating leprosy (or Hansen’s disease), caused by M. leprae, a close relative of tuberculosis. Based on its modern distribution in the tropics and subtropics, where it is associated with poverty, one would not have predicted that the disease was once prevalent in Northern Europe, where its presence has been confirmed by human remains

Figure 10 Space-occupying lesion of the sacrum in a suspected case of gastrointestinal tuberculosis from Medieval Fish-ergate, York, UK. Photograph of the author, courtesy of York Archaeological Trust.

Figure 11 Sculpture of the parable of Lazarus from the Cistercian Abbaye de Cadouin, Dordogne Valley, France. The leper holds an identifying clapper and shows collapse of the bridge of the nose and a lepromatous nodule on the forehead (visible in the lower middle part of the photograph). Adapted from Manchester K and Knusel CJ (1994) A Medieval sculpture of leprosy in the Cistercian Abbaye de Cadouin. Medical History 38(2): 204-206.

Figure 8 Vertebral kyphosis (anterior bending) due to collapse of the vertebral column from the destruction of vertebral bodies by M. tuberculosis from Medieval Wakefield. Photograph courtesy of Jean Brown from the collections of the UKBiological Anthropology Research Centre (BARC), University of Bradford.

Figure 9 Visceral surface rib lesions from Anglo-Saxon Adding-ham, West Yorkshire, UK, visible as shiny bands indicative of respiratory infections, including tuberculosis. Photograph courtesy of Jean Brown from the collections of the Biological Anthropology Research Centre (BARC), University of Bradford.

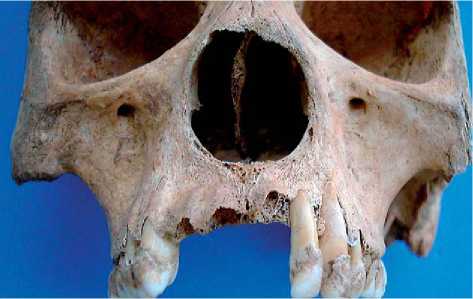

Recovered in Denmark and Britain in large numbers, as well as elsewhere. Due to its biblical associations, the disease also contributed to a highly representative artistic depiction in the period (Figure 11) that demonstrates detailed familiarity with the facially disfiguring and symmetrical (i. e., affecting both limbs) lower limb infections that are complicated by motor and sensory neuropathy. Palaeopathological studies have clarified the unique characteristics of the disease including the rhinomaxillary syndrome That develops from direct infection with M. leprae (Figure 12), unique circumferential remodeling that leads to destruction of the phalanges (Figure 13), the latter as a consequence of motor and sensory neuropathy that exposes the feet and hands to ulceration and

Figure 12 The rhinomaxillary syndrome of leprosy with characteristic rounding of the margins of the nasal aperture in a Medieval individual from Chichester, West Sussex, UK. Photograph courtesy of Dr. Alan R. Ogden from the collections of the Biological Research Centre (BARC), University of Bradford.

Figure 13 Circumferential remodeling (thinning) of the shafts of the phalanges and joint destruction associated with the neuropathy of leprosy from Medieval Chichester. Photograph courtesy of Prof. Donald J. Ortner, Smithsonian Institution, from the collections of the Biological Research Centre (BARC), University of Bradford.

Infection. The disappearance of the disease in the Medieval period may not only be attributed to the rise of tuberculosis, which confers immunity from leprosy (but not vice versa as evidenced by tuberculosis claiming the lives of many sufferers of Hansen’s disease today), but may also be as a consequence of medieval segregation of sufferers in leprosara, which Were founded in large numbers in the Middle Ages by wealthy benefactors as a sign of Christian charity.

Treponemal Disease

The treponemal diseases consist of four closely related ailments caused by a spirochete (bacterium) of the genus Treponema. Controversy exists as to whether these are manifestations of one disease that changes its expression under differing environmental and social conditions (the unitarian hypothesis), or whether the four types are separate diseases that evolved from a now-lost common ancestor (the non-unitarian hypothesis). The most geographically circumscribed form, found in the American tropics, is pinta, a skin disease, which affects adolescents and young adults and is transmitted by skin-to-skin contact. It has no osseous manifestations.

The treponemal diseases, in a similar way to leprosy, expandeD their geographic range during the Medieval period, affecting people throughout Europe, despite the fact that they are largely diseases of the tropics and subtropics today. Poor diet, inadequate and crowded living conditions, illicit sexual behavior, and the social and psychological disruptions of warfare may all have compromised or lowered the immunity of individuals to treponemal disease. All forms are recurrent and debilitating.

The occurrence and spread of syphilis is bound up with the political turmoil of Late Medieval and Early Renaissance Europe and the ‘Age of Discovery’, when its manifestations took their toll on the warring armies and populations of the Italian city-states and European monarchies. As a consequence, the disease came to be known by a series of ethnic labels (the French pox or Morbus Gallicus, the Spanish plague or Lues Hispani-cus). Controversy has since surrounded the origins of the disease, whether it was a disease of the New World brought to Europe by the crews of exploring sailing vessels, or rather it is an older disease that underwent epidemiological change at this time. Syphilis, the venereal form of the disease, became a highly visible public health concern in Europe, as much as a consequence of the hushed atmosphere that surrounds sexual activities and their association with illicit deviancy as due to its debilitating effects. Recent studies demonstrate that a number of named aristocrats, both male and female, suffered from the venereal form, as did those of less lofty social origins.

Yaws, a disease of the tropics today, and bejel (also called nonvenereal or endemic syphilis or treponarid), a disease of the arid regions of Southwest Asia and the Balkans, are nonvenereal forms of the disease that affect infants and young children and are transmitted by contact with early and open spirochete-containing lesions. Their physical manifestations are almost

Sources: Steinbock, R T (1976) Paleopathological Diagnosis and Interpretation. Springerfield, IL; Thomas, CC, Aufderheide, AC and Rodriquez-Martin C (1998) The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Human Paleopathology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Note that yaws may affect the neurocranium in some cases and may have done so with greater frequency in the past.

Identical and are also similar to those produced in venereal syphilis (Table 1). All produce cutaneous and mucosal rashes that, when transmitted to bone (in less than 1-5% of cases), elicit inflammatory periosteal new bone formation and destructive granulomatous lesions called gummas. The nasopalatal region and tibiae (producing characteristic ‘saber-shin’ deformities) are more often predilected in yaws and bejel, whereas, neurocranial involvement, referred to as caries sicca, is more severe and more common in venereal syphilis, although it is found in a small percentage of yaws and bejel sufferers. Due to the similarity in bone involvement, it is very hard to distinguish the venereal form from the nonvenereal forms. Venereal syphilis is the only one of the group that produces neurological manifestations (tabes dorsalis), although these do not produce diagnostic bone lesions. Importantly, however, syphilis is also the only one of the treponemal diseases that can be transmitted transplacentally, producing characteristic dental dysplasias in the form of Hutchinson’s incisors and mulberry (i. e., multi-cusped) molars. These dental lesions of congenital syphilis, then, are most sought after by palaeopathologists interested in the origin and spread of the venereal form.

World History

World History