The first human-like inhabitants of Southeast Asia were the early hominins - members of the wider human family - known as Homo erectus. The first fossil remains of this species were discovered in central Java by Dutch Colonial medical officer Eugene Dubois in 1890, who named it Pithecanthropus erectus, the ape man who walks upright. Further remains of H. erectus have since been found at several sites in central Java. The dating of the fossils is problematic, but recent evidence supports dates of at least 1 million years ago, if not more. It is generally accepted that these fossils represent one of the earliest forays of hominins out of Africa, but whether they were the direct ancestors of modern humans is more controversial. A continuing debate was initiated by DNA research in the 1980s which suggested that modern humans emerged from Africa at a much later date, supplanting earlier hominins in places like Southeast Asia. The older view, which seems to be losing ground, was that H. erectus types migrated from Africa to many parts of the world including the Middle East, Europe, and China as well as Southeast Asia and there evolved into subtypes of modern humans (see Modern Humans, Emergence of).

One of the problems with the H. erectus fossils in Java is their lack of clear association with any cultural material. The earliest humans in Africa are defined as human ancestors at least in part by their ability to make and use patterned stone artifacts, objects which can be considered cultural by virtue of their being passed on within the social group by processes of learning. Stone artifact assemblages made by H. erectus have been claimed from various parts of Java, but none is unequivocal in terms of stratigraphic location, absolute dating, and artifactual status. A badly defined industry called the Pacitanian has been recognized from a series of surface sites and attributed to H. erectus, but has not been shown to be in association with any fossils, nor has it been dated. Recent accounts suggest artifactual evidence has been found in excavated stratified situations in central Java, but detailed reports are needed to

Confirm this. The lack of universally accepted, clearly associated artifactual evidence in Java might be taken as suggesting that Javanese H. erectus was not a likely ancestor for modern humans.

While the ‘classic’ H. erectus remains from Java are generally accepted as being at least 1 million to 750 000 years old, another group of remains, mainly from Ngandong on the Solo River in central Java, are considered to be more phylogenetically evolved and therefore more recent. Again, their dating is problematic, with some claims that they might be as recent as c. 30 000 years old, but a more generally accepted dating would be of the order of 300 000 years. Like the others however they are not, to the agreement of all, associated with any cultural remains.

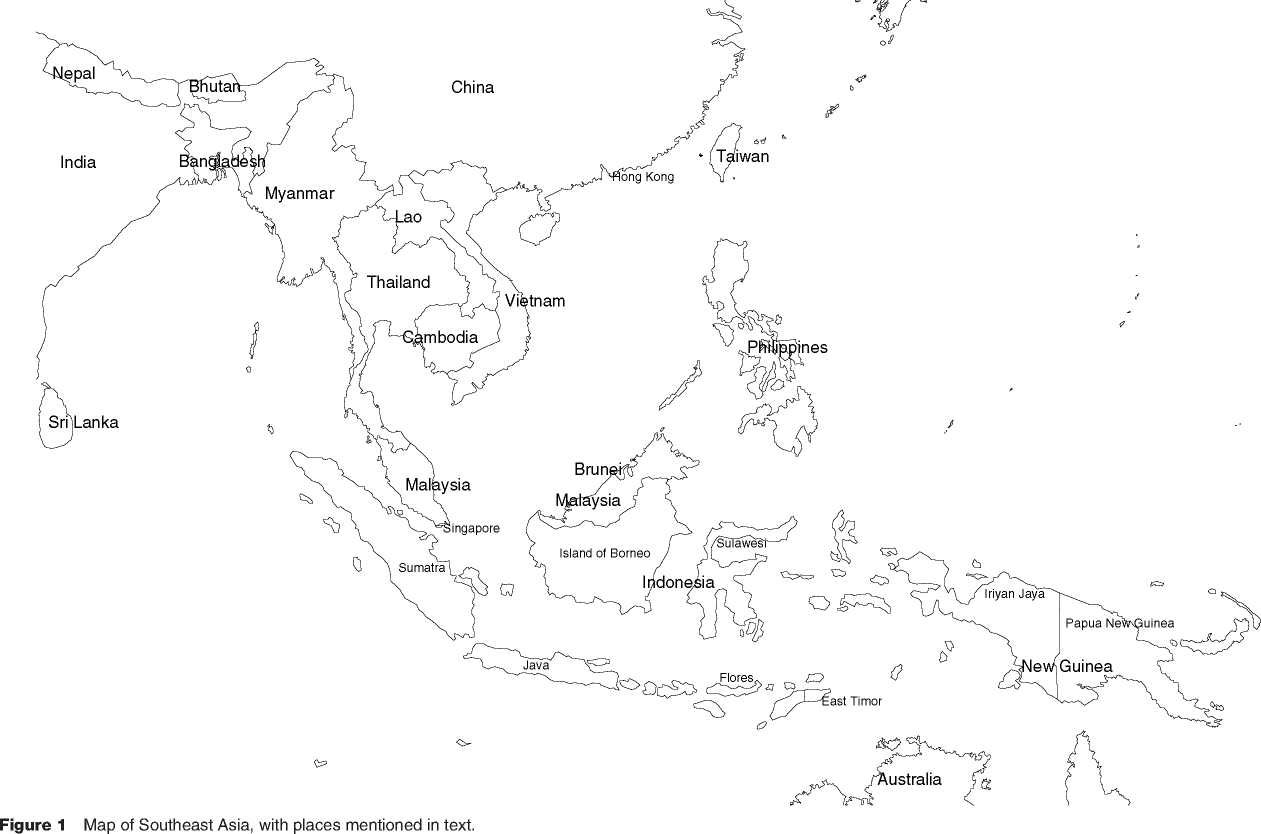

Research in Flores, one of the islands in the eastern Indonesian archipelago, has revealed new evidence. During the Pleistocene, there were periods of lowered temperatures worldwide which froze up much of the world’s water into glaciers and thus lowered sea levels. Java, being part of the Sunda shelf, was connected to mainland Southeast Asia by a landbridge during such periods. Flores lies in one of the deep troughs between Sunda and Sahul and was thus only ever accessible by water. While it is easy to imagine H. erectus arriving dry-shod in Java, it seems less likely that this early hominin would have crossed such a barrier to Flores. Finds in the Soa Basin of central Flores seem to suggest that this might have been the case. While no actual hominin remains have been found here, stone artifacts dated to c. 800 000 years ago suggest that H. erectus was here at this time. There is however continuing debate about the nature of the artifacts and their stratigraphic associations. It can be observed that in Java we have fossil hominins with few if any indisputable cultural associations, whereas in Flores we have putative hominin cultural remains but no hominins. More recent and equally challenging evidence from Flores has been recovered recently, and will be discussed further below.

Evidence of H. erectus is lacking from the Southeast Asian mainland, despite its presence in southern China by at least 750 000 years ago and possibly earlier. There is also no convincing cultural evidence of an early occupation of the mainland.

Furthermore, there appears to be a wide chronological gap between these early residents of island Southeast Asia and later hominin occupations in the form of modern humans, H. sapiens sapiens. Anatomically modern humans (AMHs) are now generally accepted as having evolved in Africa some time between 200 000 and 100 000 years ago, and to have spread out to the rest of the world between c. 100 000 and 40 000 years ago, or during the early part of the Upper Pleistocene geological epoch.

AMH fossils are found in the Middle East dated to c. 100 000 years ago, and in Europe by c. 40 000 years. The oldest modern humans in China are dated no older than 67 000 years ago (Liujiang). The Southeast Asian evidence for modern humans conforms to this pattern. Where it differs is in the nature of the associated cultural evidence, especially with respect to stone artifact assemblages.

World History

World History