South Asia as an ancient culture area is inconceivable without consideration of the firm foundations provided by the prehistoric phase spanning more than a million years of hunting and foraging way of life. The terminal stage of this preliterate life, called the Mesolithic, is dated to the early part of the Holocene and merges into the succeeding agro-pastoral stage comprising various Neolithic-Chalcolithic cultures and the Indus civilization. The present essay seeks to provide a review of the existing evidence pertaining to the preceding Palaeolithic stage, which comprises three phases (Lower, Middle, and Upper) and is dated to the Pleistocene.

Geographical Features

South Asia occupies a middle position among the three peninsular projections marking the southern margin of the Asiatic landmass. It comprises the Himalayan kingdoms of Nepal and Bhutan, the island nation of Sri Lanka, and the sovereign states of India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. In the north, South Asia is separated from the main Asiatic land-mass by the high Hindukush and Karakoram ranges, and the Himalayan massif proper. On the western, southern, and eastern sides, the Indian peninsula is neatly marked off by the Arabian Sea, the Indian Ocean and the Bay of Bengal, respectively. Notwithstanding its status as a distinct geographical unit, outside influences did reach the South Asian region by both land and sea from the very beginnings of human life, such that its cultural make-up is a combined product of both outside stimuli and internal development.

Within this larger geographical entity, there is tremendous regional diversity. The major topographic subdivisions include the arid zone of Rajasthan in the west; the high snow-clad Himalayas in the north; the hill-tract of northeastern India supporting a rich tropical rainforest ecosystem; the vast Indus and Gangetic alluvial plains which served as the springboards of First and Second Urbanizations, respectively; and the triangular-shaped plateau of peninsular India. The peninsular block is flanked on the western and eastern sides by narrow hill-chains running close to the seaboard and is drained by east-or west-flowing rivers. Sri Lanka is situated some 20 km off the tip of the peninsula; central highlands, northern lowlands, and southern rolling plains are its chief geographical units.

South Asia is an area of monsoonal climate which originated due to the upthrust of the Himalayas and Tibetan plateau, the final phase of which is dated to about 14 Ma. Much of the peninsular block receives its precipitation from the southwest monsoon. The northern mountainous tract lies in the winter rainfall belt of Northern Hemisphere; moisture comes in the form of winter storms or snow melt. The extreme southern part of the peninsula as well as Sri Lanka benefit from the rainfall caused by the northeast monsoon.

History of Research

Prehistoric research started in South Asia immediately after the epoch-making discoveries of stone stools by Boucher de Perthes in the Somme river gravels of northern France in the mid-nineteenth century. The ratification of these findings by the Royal Society in London in 1859 was a great source of inspiration to Robert Bruce Foote who came to Madras (now Chennai) in 1858 as a young officer to work in the Geological Survey of India. Foote found a few bifacial stone implements in a lateritic gravel pit near Madras in May 1863. In the course of his three-decade-long geological surveys in various parts of southern India and Gujarat, he located a large number of prehistoric sites which he classified under three periods - Palaeolithic, Neolithic, and Iron Age. His publication entitled The Foote Collection of Indian Prehistoric and Protohistoric Antiquities: Notes on Their Ages and Distribution, published in 1916, is the first major synthesis of South Asian prehistoric research and still offers many useful insights into the environmental settings and lifeways of prehistoric populations. Foote is therefore rightly called the ‘Father of Indian Prehistory’.

The next phase, spanning from the 1930s to the 1970s, witnessed the rise of what may be called the stratigraphical-cum-cultural-cum-climatic sequence paradigm. During this period efforts were made to divide the Stone Age into various phases based on stratigraphical evidence, as supplied by river sediments and other deposits. Based upon the character of these deposits (gravels, silts, etc.), inferences were also made about past climates consisting of a succession of wet and dry climatic episodes. Four major studies were involved in the development of this paradigm: (1) the work of L. A. Cammiade and M. C. Burkitt on the southeast coast of India postulating the existence of four successive cultural stages (series I-IV); (2) joint investigations of the Yale and Cambridge Universities in the Potwar plateau and Kashmir Valley, and the formulation of Soan culture-sequence with reference to alternation of glacial and interglacial episodes; (3) the work of F. E. Zeuner of the Institute of Archaeology, London, in Gujarat and the Deccan seeking to identify the stratigraphical contexts of Palaeolithic and Mesolithic assemblages with reference to alluvial and sand dune deposits; and (4) H. D. Sankalia’s reconstruction of fourfold cultural sequence (series I-IV) based upon his study of cliff-sections of the river Pravara at Nevasa in the Deccan. From the mid-1950s to mid-1970s, this paradigm was extended to many other parts of India. Simultaneously, some important Stone Age sites were reported from other parts of South Asia, such as the Sanghao cave from Pakistan and the Ratnapura industry from Sri Lanka. Indeed, the emergence of Stone Age archaeology on the academic scene in South Asia was epitomized by the publication of the second edition of H. D. Sankalia’s book Prehistory and Protohistory of India and Pakistan in 1974.

The third phase, which was initiated in the late 1970s, reflected the advent of New Archaeology into the region. It began to be realized that stone artifacts recovered from secondary deposits such as alluvial gravels and silts could not serve as secure data for making behavioral interpretations. Also it was felt that interpretations about past climate based on alluvial deposits were not sound. Against this background a fresh approach was initiated in the South Asian Stone Age research. Its chief components were: (1) region-based intensive field-surveys; (2) emphasis on the identification of in situ sites and their careful investigation, employing the perspective of formation processes; (3) use of both biological and Earth sciences in palaeoenvironmental reconstructions; and (4) use of experimental and ethnoarchaeological analogies. In an accompanying paradigm shift, culture was redefined as a systemic whole and as a means of human adaptation, rather than being treated as a mere vehicle for arriving at classificatory and descriptive definitions.

During the last quarter-century, several projects employing some or all of these strategies were carried out in the Siwalik hills of India and Pakistan, central India covering the Belan, Narmada and Son Valleys, arid tract of Rajasthan, Saurashtra, the Deccan uplands, Chotanagpur plateau, and South India. In more recent years, some important studies were undertaken in the Deccan, the Bhima and Kaladgi Basins of north Karnataka, and the Kortallayar Basin of south India. Sri Lanka and Nepal also yielded evidence of Stone Age occupation. Discovery of fossil hominid remains at Hathnora in central India and Odai in south India, and the use of various radiometric methods for dating Stone Age sites are two other major developments of this phase.

Some of these more recent projects benefited from collaboration with research teams from Cambridge, Oxford, Sheffield, and Sussex universities in England, University of California and the Smithsonian Institution in the US, and Australian National University and Marquarie University in Australia. Scientific institutions in India like the Physical Research Laboratory, Ahmedabad, Central Arid Zone Research Institute, Jodhpur, Geological Survey of India, and Anthropological Survey of India also participated actively in some of the regional investigations. These joint studies were particularly helpful in attempting palaeogeo-graphic and palaeoenvironmental reconstructions.

Palaeoenvironments

In the Pleistocene, which has a duration of 2.5 Myr, South Asia was a part of the global climatic set-up. Oxygen-isotope studies of ocean-bed sediment cores established a repeated alternation of cold and warm periods. During the last 1 Myr, 9 or 10 glacial/intergla-cial cycles occurred. During glacial periods in northern latitudes, the monsoon was weak in South Asia and dry climate prevailed. When the northern latitudes were experiencing interglacial climate, the monsoon was strong in South Asia resulting in a wet climatic episode with a high level of precipitation. Although for want of clear data it is not possible to correlate the Palaeolithic cultural stages in South Asia with any specific climatic episodes, sedimentary data from fluvial and other contexts in the Kashmir valley, western and central India, and the Deccan region revealed a succession of wet and dry or arid and humid phases. Some of these studies deserve mention here.

Employing the technique of pollen analysis, D. P. Agrawal and his team reconstructed a long and detailed palaeoclimatic sequence for the Kashmir Valley. The area experienced a warm temperate climate up to 3.8 Myr. From 3.7 to 2.6 Myr the climate changed from subtropical to cool temperate type. Cool climate persisted in the area for 2 Myr. The last 200 kyr saw the building up of a thick deposit of loess due to wind activity. Separating the periods of wind activity were periods of climatic stability as revealed by the formation of palaeosols. H. D. Sankalia found a few stone artifacts in the alluvial conglomerate at Pahlgam and dated them to the first interglacial period. Subsequent work in the area confirmed that at least from the Late Pleistocene the area was occupied by Stone Age groups in a regular way.

The prolonged research of the British Archaeological Mission led by Robin Dennell from 1980 to 1990 in the Potwar plateau of Pakistan resulted in a wholesale re-evaluation of the Quaternary glacial/interglacial terrace stratigraphy and Soan culture-sequence put forward earlier by H. de Terra and T. T. Paterson. The terraces proved to be only erosional features and non-glacigenic. Similarly, the Stone Age cultural material was found on surface in secondary contexts and hence it was found unsuitable for fixing culture sequences. However, this recent work produced new discoveries - two Acheulian sites at Dina and Jalalpur dated between 700 and 400 kyr and a possible Lower Pleistocene Early Man site at Riwat near Peshawar dated to 1.9 Myr by means of palaeomagnetism.

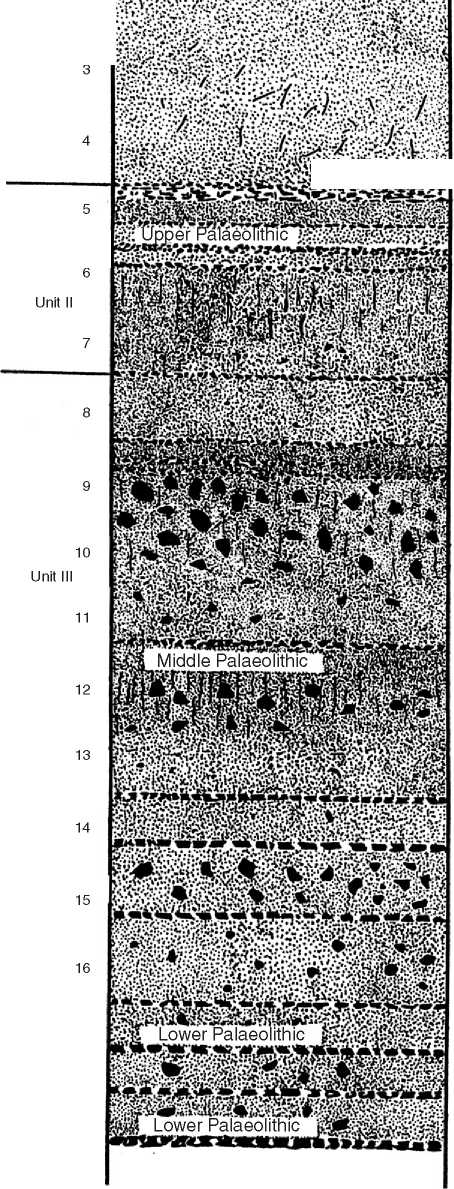

The western part of Rajasthan, now mostly occupied by the Thar Desert and its characteristic sand dunes, provided sound evidence for reconstructing palaeoenvironmental history and human adaptations. In the Pleistocence the area was a favorable habitat for Stone Age communities. The work of Bridget Allchin and others in the 1970s showed that the area witnessed two major dry periods separated by wet climatic episodes. Palaeolithic and Mesolithic groups occupied sand dunes overlooking shallow water pools and other favorable micro-niches. In the 1980s the team led by V. N. Misra carried out further work in the area and identified three major Quaternary sedimentary units called the Jayal, Amarpura, and Didwana formations. This multidisciplinary research involved excavations at Singi Talav and Didwana (16 R locality) and made it possible to reconstruct a detailed history of climate and landscape development. The 20 m deep trench at 16 R locality exposed a series of five major paleosols, sixteen calcrete bands, and well-dated cultural material belonging to the Lower, Middle and Upper Palaeolithic, and Mesolithic stages (Figure 1). During the Early Pleistocene the present-day waterless sandy plains of the region supported large streams originating from the Himalayas, which laid down extensive and thick gravel beds in Nagor and Jodhpur districts. Man was absent. Subsequently, these beds were tectonically uplifted and new streams with wide flood plains marked with pools and lakes were formed. The Palaeolithic groups camped around these pools and ponds and also on the exposed gravel beds. The climate during this period was basically semi-arid, but it alternated several times between cool dry and warm wet periods. Sand sheets and dunes were formed in cool dry periods and their surfaces were stabilized during the subsequent wet phases. Palaeolithic groups occupied the stabilized sand surfaces.

In central India the middle stretch of the Narmada preserved thick deposits of gravels, silts, and clays broadly classified under a Lower Group and an Upper Group. This sedimentary record, basically alluvial in nature, yielded rich evidence of mammalian fauna and Stone Age cultural record. The recent hom-inid findings at Hathnora brought this area into focus

Figure 1 16 R sand dune section at Didwana, Rajasthan, showing sedimentary stratigraphy and Stone Age culture sequence.

Once again. The University of Allahabad team, in collaboration with the universities of California and Melbourne, worked in the Belan and Son Valleys of north central India and identified gravel and silt deposits grouped under Baghor, Sihawal, Patpara, and Khetauni formations. Various phases of the Stone Age were correlated with these sedimentary bodies.

In the Deccan region the basins of the rivers Godavari and Krishna and their various tributaries were the scene of Quaternary studies for the last half a century. These preserved rich and continuous record of Stone Age occupation including animal fossils. In the northern Deccan geoarchaeological work during the last two decades led to the recognition of four major Quaternary formations - Bori, Godavari, Upper Bhima, and Chandanpuri formations - containing valuable data for reconstructing Stone Age culture sequence against the background of Quaternary climatic history. Following upon the pioneering work of R. V. Joshi, important fresh field studies were carried out in the Bhima and Kaladgi Basins of north Karnataka and also in the Kortallayar Valley of Tamil Nadu. These yielded important fresh data bearing upon reconstruction of palaeogeography and settlement patterns of the Palaeolithic times.

Faunal collections obtained from different parts of South Asia prove that the Quaternary landscape supported rich animal world. The Karewa beds of Kashmir and the Siwalik hills of the Punjab and Himachal Pradesh produced Lower Pleistocene fauna. Similarly, the sediments of the Godavari, Narmada, Krishna, Belan, Son, and other Peninsular Indian rivers yielded fossil fauna comprising various species dated to the Middle and Late Pleistocene. The Kurnool caves in the southern part of the country and the Ratnapura beds of Sri Lanka also yielded rich faunal assemblages. As regards the plant world, it is inferred that as is the case today the South Asian landscape supported a cross-section of vegetation types comprising the Alpine type geared to glacial landscape, evergreen forest system, deciduous vegetation, savanna grasslands, and scrub vegetation. From the wide spatial distribution of Palaeolithic sites, it is clear that man was adapting himself to various environmental settings during the Pleistocene.

World History

World History