Falling snow flakes and steamy breath from frost-rimmed nostrils blurred the view of Old Long Clitoris. She was so named because of the unusual size of what is normal anatomy of female hyenas, often and falsely believed to be hermaphroditic. She was trying to see into the short twisting canyon wherein a small group of humans huddled in a gray limestone cave whose wide opening was level with the snow-covered canyon floor. The little canyon stream was frozen solid. Providing some protection from the icy afternoon wind, the cave entrance faced out upon the frozen treeless steppe that stretched far beyond the distant horizon. In thousands of years to come, this vast land would be called Siberia. Now, it had no general name. Only specific places had names, like the cave, which was known as “two-eyed” cave, because through the darkened ceiling light entered from two round openings, giving the feel of a monstrous, watching cave lion. Aside from a few miniature and deformed willow bushes rooted to the canyon walls, the only other fuel for a warming fire was a copse of dwarf birch trees rooted in the canyon’s thinly soiled floor. The humans knew the canyon was a dangerous place since there was no way to escape should any predators enter the canyon mouth. But what choice did they have in their storm-stalled southward trek - stay in this

Fig. 1.10 Odyssey. Afternoon dinner. We were guests of Galina Erosiva who, helped by her daughters (right), put on a table full of traditional dishes and drink, including tea and lots of home-made vodka (arachka) distilled from fermented cow’s milk (the five-gallon stainless steel milk can in the lower right was full of freshly made vodka).The senior author noted: “We had [a] lavish meal of potato and meat soup, sour cream, fTesh bread (Altaic and Russian styles), two kinds of home-made jam, butter, tea with milk, milk vodka, egg salad, a cottage cheese and onion salad, buckwheat, and candy.” The aiyel had a central fire hearth on the earth floor directly below an open smoke hole in the center of the roof. Smoke from the smoldering wood fire, the smell of roasting meat, the yeasty aroma of fresh-baked bread, and other smells reminded the senior author of his earlier anthropological days on the Navajo and Hopi Indian reservations of northern Arizona. Substituting animal hides for the colorful rugs hanging on the walls, and removing the modern utensils and furniture, one can easily imagine aiyel-like structures as having been the winter residences of the Paleolithic Altai people. Wind-proof, easily heated, and erected near firewood sources, aiyel-like structures would have been much better winter residences than the cold drafty archaeological cave sites. While the cave sites are not hard to find, open habitation and camp sites like Mal’ta and Afontova Gora depend on considerable luck to locate. Left to right: Nicolai Ovodov, Olga Pavlova, Sergei Markin, Galina Erosiva, and her family (CGT neg. Karakol 7-10-99:24).

Bone-littered shelter that had been occupied by carnivores, or freeze to death like the stiff gazelle carcass that the people had stumbled across on the snow-covered steppe not far from the mouth of the canyon. Ancient habits had taught them to eat meat raw, or briefly cooked as soup warmed with heated stones dropped into a skin bag containing meat, crushed bone, melted snow, and pieces of aromatic plants. Earth ovens worked only when the ground was not frozen. Either way, the food was more nutritious than when roasted, despite the mouth-watering smell of wood smoke and fatty, roasting

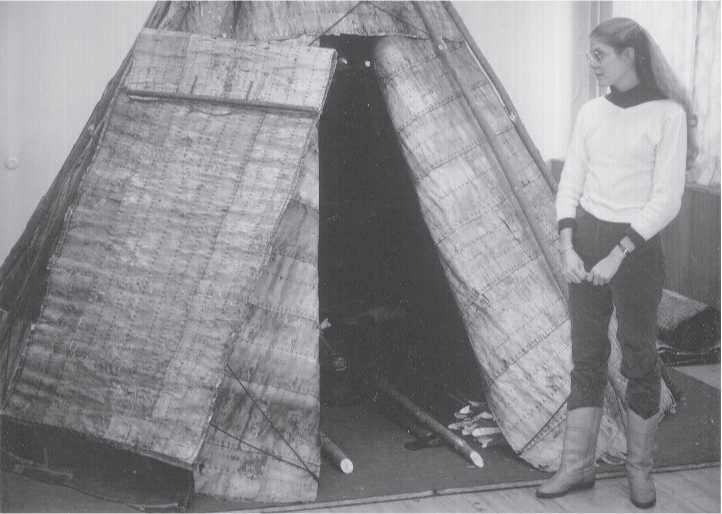

Fig. 1.11 Odyssey. A camping tent. Shown is a lower Ob River Sel’kup bark tent. Light and easily

Transported, this type of structure was favored by fishermen, hunters, and trappers. Constructions like this might have been erected in the Altai cave sites, but unquestionable tent rings and post holes are unknown. Korri Dee Turner (right) (CGT color IHPP 2-13-84:21).

Meat. Besides, the humans dared not gather branches from the birch thicket this late in the day because they feared that some carnivore might be hiding there.

As night came on, a shift in the wind brought whiffs of animal smell from the little forest. Hyena stink! Many! The humans knew that 50 (counted by the fingers of five people) or more adult animals were common in a hyena pack, many more than the number of the human band. Hyenas were not only ferocious killers, they ate anything - including humans - live or long dead. When hungry they were the most dangerous of the big carnivores because they hunted in packs of many individuals, unlike the more solitary bears and lions. Even wolf packs avoided confrontations with hyenas because the hyena’s powerful jaws could crush a leg or head in an instant. Hyenas were cruel killers and never revered as were the cave lion and other Ice Age predators. The group’s powerful shaman, an old deformed man given to fits, fondling the group’s young boys, and unerringly able to predict future events, said hyenas were evil. Even his guardian spirit, a tiny but frightful vole, had no power to combat them.

Despite her age and many battle scars, Old Long Clitoris had perfect unbroken and unworn teeth, her reward as matriarch to command the best soft meat and internal organs from a kill. Low-ranking family members had chipped, cracked, and worn

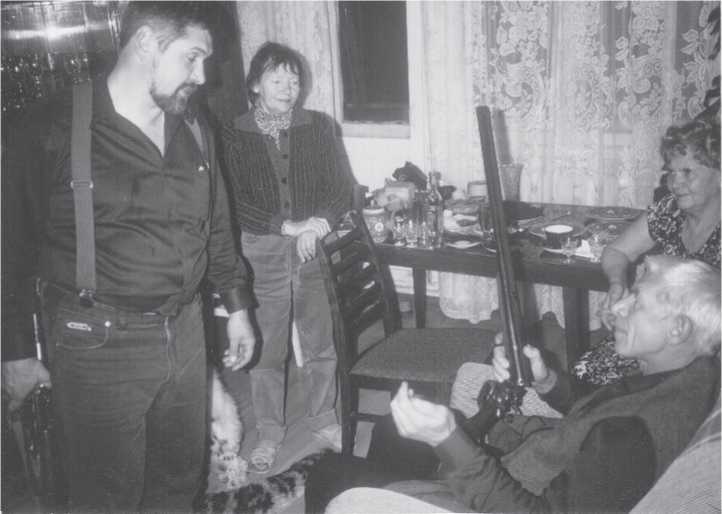

Fig. 1.12 Odyssey. A modem hunter. Professional hunter Demitry Medvedev, son of German Medvedev (Fig. 1.17), shows Olga Pavlova (center) and Nicolai Ovodov (right) two of his shotguns. Medvedev’s mother is at far right. The photograph was taken in Irkutsk after a day traveling by fishing boat along the southwest coast of Lake Baikal. In his youth Ovodov did a lot of hunting. On one outing he killed a large bear with his single-shot rifle - the only kind of firearm a person could possess legally in the former Soviet Union (CGT color Irkutsk 10-5-00:12).

Teeth because they had to often eat the less desirable hard bones, horns, and hooves. Frost also covered the sloping, spotted back of Old Long Clitoris, whose shaggy fur rose and fell in the gusty, cold, snow-flecked wind. Nevertheless, her aged hearing relayed to her small but highly intelligent brain the sounds of bones being smashed open by the people, and her starving sense of smell told her that meat and marrow were being eaten, meat and bone fat that she wanted for her own starving body. Old Long Clitoris was not alone in watching the humans. Others of her clan were also crouching in the birch stand and, like her, had not eaten for the many days that the winter storm had made finding food nearly impossible. They were now full-time scavengers, not having seen a living animal in the past 15 days, except for occasional watching ravens. What made matters even worse, the humans were huddled in the sheltering cave that she and her ancestors had often used in stormy emergencies for tens of thousands of winters.

She had learned through many seasons of experience that there were two kinds of humans, just as there were different kinds of look-alike horned creatures she killed and devoured. The older kind of humans were dangerous, but not as much as the humans who arrived recently. But cold and scarcity of food were now worse than any time in her many

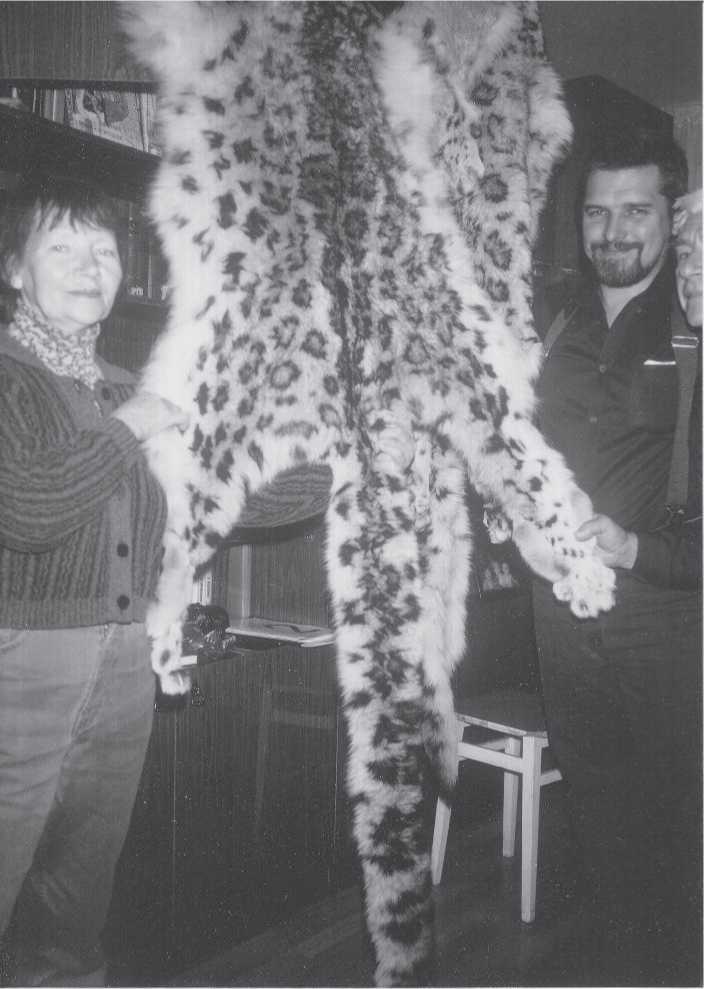

Fig. 1.13 Odyssey. Snow leopard pelts. Demitry Medvedev shows Olga Pavlova and Nicolai

Ovodov two pelts of the very rare snow leopard. Winter-killed pelts like these would have been valuable to the Paleolithic Siberians for warmth as well as symbolic and status purposes (CGT color Irkutsk 10-5-00:7).

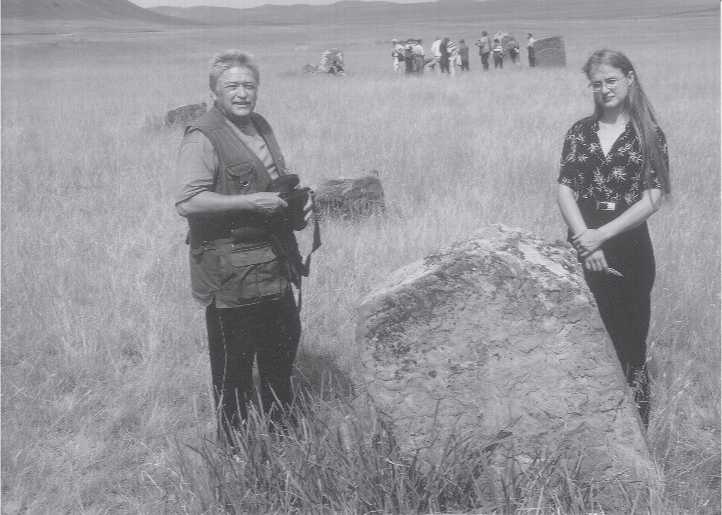

Fig. 1.14 Odyssey. Archaeological site tour. Travel during our project included the use of various

Forms of water-craft. In this image, Nicolai Drozdov (left) and Olga Pavlova board a patrol boat near Kurtak, joining others for a day-long tour of Paleolithic archaeological sites discovered and excavated by Drozdov and his team along the upper lake level of the Yenisei River Reservoir. While thousands of Pleistocene animal bones are washing out of the loess shoreline, few have been found in the Yenisei Reservoir archaeological sites. This lack of preservation seemingly adds to the view that some of these sites are very ancient; either that or many of the artifacts have been redeposited. The regional vegetation is steppe and forest parks. CGT notes for the day included: “Day was clear, warm, and very enjoyable. Dinner was beef shishkabob, cucumbers, bread, cabbage, peas, onions and lots of vodka” (CGT color Kurtak 8-7-98:11).

Years as the born-to-be matriarch of the family. Sooner or later, as has happened before, a young or elderly human will wander away alone, separated fTom the safety of its group. Then, she and her fellow hunters could attack and carry the torn body to another shelter elsewhere in the thinly pine-forested limestone foothills. Hunting solitary humans in the winter, when a child wandered away from the protection of its terrifying fires and barking little wolves, became ever more common as the winter cold deepened and lasted longer, season after season. Summers barely began when the first fTosts arrived. These earlier, colder, and longer-lasting winters started the southward migrations of the great herds of hoofed creatures, drove underground the many kinds of small, tasty, chisel-toothed species, and brought life to a cold desperate standstill. The world had changed to a terrible, never-ending, lifeless cold that far in the future human scientists would call the Late Glacial Maximum.

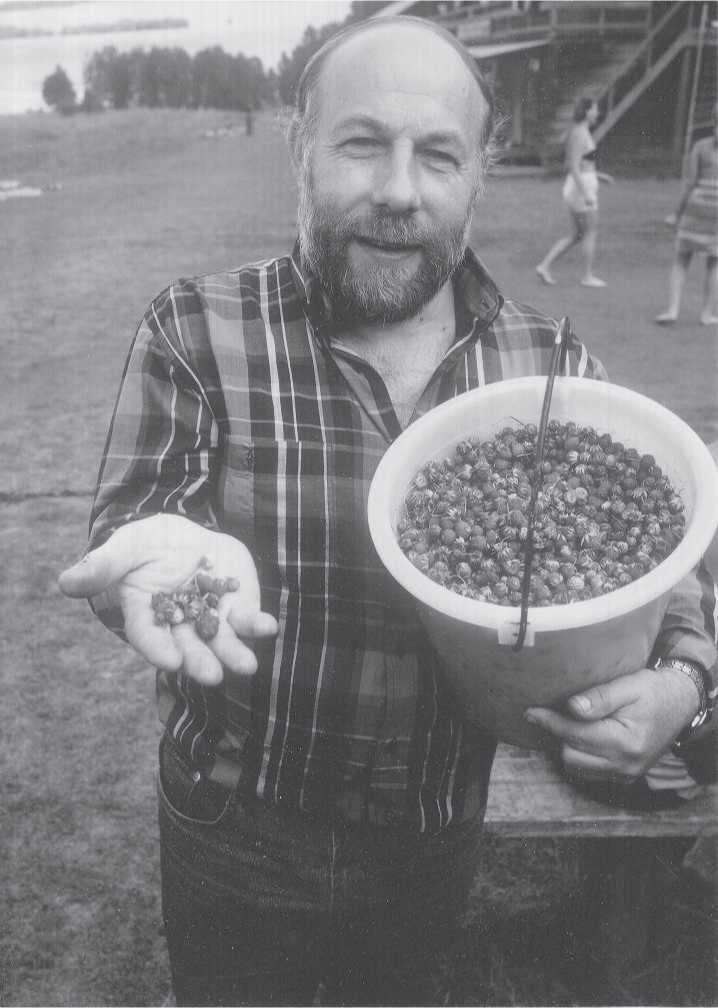

Fig. 1.15 Odyssey. Wild strawberries. Along the tour mentioned in Fig. 1.14, we stopped at a summer camp for young people. Here, Nicolai Drozdov was shown a pail full of small wild strawberries that had been gathered that day. Made into a jam, they are delicious and have an over-powering fruity fragrance. Drozdov is not only a renowned Siberian Paleolithic archaeologist, he is also President of the Krasnoyarsk Pedagogical University (CGT color Kurtak 8-4-98:20).

Fig. 1.16 Odyssey. Irkutsk station. Ovodov and Pavlova at the Irkutsk train station as snow was falling in early October. We had just completed a lengthy study of some of the Mal’ta faunal remains at the Archaeological Laboratory of Irkutsk State University, and were returning to Novosibirsk (CGT color Irkutsk 10-8-00:29).

Fig. 1.17 Odyssey. Examining graves. German Medvedev and his wife, Ekaterina A. Lipnina. Steppe grasses are abundant here. Out of sight in the background is a land-locked saline lake 376 m above sea level, only a few kilometers ITom the Yenisei River, and 272 km south of Krasnoyarsk (CGT color Kurtak 7-28-00:3).

Fig. 1.18 Odyssey. Ulan-Ude celebration. East of Lake Baikal, in even more severe steppe country,

Referred to as the Trans-Baikal or Buryatia, the capital of which is Ulan-Ude. The image shows a national Buryat holiday that occurred during our visit. The ceremony was taking place on a Saturday in the city’s central square. Costumes have a strong Chinese influence. The Buryat Republic was formed 80 years ago under Soviet direction. The city itself is, however, 337 years old. Here we studied the large faunal collection from Kamenka excavated by Ludmila Lbova (CGT color Ulan-Ude 7-5-03:19).

Hunting the lone victim in overpowering numbers was an ancient strategy of many predators, but her kind excelled by the fact that they hunted as well at night as during the day; they were a well-coordinated hunting team; they had evolved digestive and dental systems that extracted nutrients even from the bones and teeth of their victims. No other predators were this efficient. In this way they could extract nutrients from the bones, hooves, even fur left at kills by lions, wolves, and all other large predators. Unlike the more solitary hunters of the taiga and steppe - the cave lions, cave bears, and tigers, or the easily intimidated wolves, foxes, and raptors - only the new humans who also hunted in packs were near equals. Evolution had crafted both human and hyena species to be highly intelligent, socially organized, and gifted with great endurance. Humans were able to wear down horses, for example, by forcing an animal to walk all day until it collapsed in exhaustion. The shaggy matriarch and her kind had three other advantages. First, their kind had lived in their lands for thousands of generations and knew every detail about the vast landscape and its inhabitants. The new humans knew almost nothing about the region, often making dangerous mistakes like camping in this box canyon.

Fig. 1.19 Odyssey. Attic collection storage area. Olga Pavlova and Nicolai Ovodov search for specific Paleolithic faunal assemblages recovered from excavations by members of the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography, Novosibirsk. This anthropological component separated from the original IHPP, first directed by Academician A. P. Okladnikov, with scientific assistance from Ovodov and others, has assembled the largest Siberian archaeological, ethnographic, and physical anthropological collection in Siberia, rivaling all the anthropological institutes combined in Moscow and St. Petersburg. Here, the faunal collections are curated in a very large attic space of a huge U-shaped four-story building that houses the IAE and other divisions of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Hundreds of thousands of pieces and whole bones are in this storage area. There is a severe shortage of storage space all over Siberia, as expected where even human housing is at a premium. Most of the collections we studied were curated in hot, freezing, or damp attics or basements and had to be moved to a study area (CGT IAEneg. 7-30-99:13A).

Second, she and her kind would eat humans whenever they needed, alive or long rotted. The new humans had the odd behavior of burying their dead, rarely eating them as was common in hyena packs. Despite burial, the hyena family easily found and dug up the cold, rancid bodies. There has never been news of humans eating their kind. Far in the future, archaeologists would find hundreds of rock and mobile art images of predators and other creatures. Her kind were very rarely depicted. Humans did not admire hyenas. Last, when all food resources were gone, she had less reservation about eating her own kind than did the humans. Both species were cannibalistic when desperate. While sharing many similarities with humans, her kind had superior immune resistance to disease and toxins found in rotted carcasses. While they relished freshly killed fatty game, they could live off almost anything along the scale of organic diagenesis.

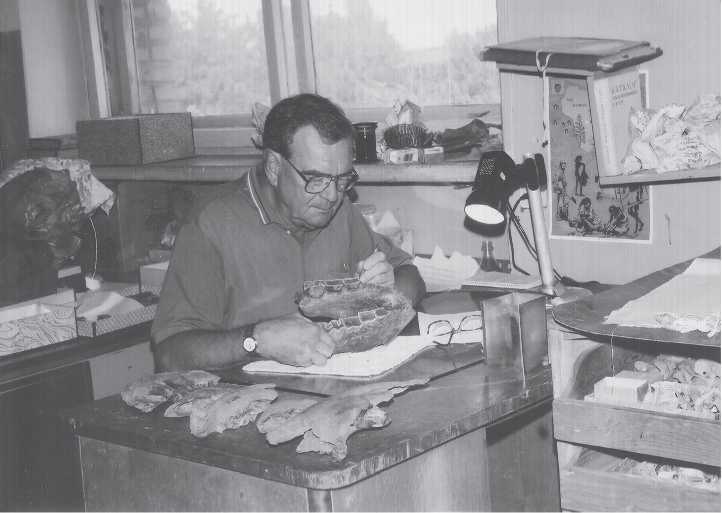

Fig. 1.20 Odyssey. In Ovodov’s little lAE laboratory, the senior author looks for bone damage in wooly rhinoceros

Mandibles from the Ob River paleontological site of Krasny Yar (CGT neg. IAE 6-21-00:32).

Fig. 1.21 Odyssey. Also in Ovodov’s lab is Olga Pavlova, who translated most of the labels and notes

Associated with each of hundreds of boxes of bones. When time permitted she translated articles describing various sites from which the faunal remains were recovered and other related publications (CGT neg. IAE 6-21-00:35).

Fig. 1.22 Odyssey. At the Institute of Paleontology, Moscow. The remaining three photographs in this chapter are to commemorate Ivan Antonovich Yefremov, the Russian paleontologist who conceived the idea of taphonomy. It is a Russian tradition to take a photograph at the plaque of a visited institute, here the “Russian Academy of Sciences Institute of Paleontology, Paleontology Museum, after Academician YelTemov.” Left to right: large-mammal paleontologist Irene V. Krilova, the senior author, and Alexander Karenovich Agadjanian, a small-mammal paleontologist who arranged for our visit to the museum. Small mammals are very sensitive to temperature, and Agadjanian has developed a marvelous late Pleistocene climate sequence for Denisova Cave based on these tiny creatures (OVP color PIPM 6-8-01:36).

Thus, with these advantages, the cave hyenas were able to keep the new human predators from over-running their territory, ruled for thousands and thousands of generations. But the terrible unending cold now was murderous. Food had become much scarcer, neutering her weaker male companions so that few of her sisters became pregnant. Her kind was vanishing.

The more recent humans thrived in the cold. They were clothed in tightly sown skins from head to foot. The older humans also wore animal skins, but their seams were sown with less precision, allowing the cold winds to suck away precious body heat that could best be replenished by eating fat. Hunting and killing large animals like the wooly mammoth produced the greatest amounts of fat. And watching the recent humans revealed to Old Long Clitoris that these kinds of humans were much more skilled hunters than the old humans. Moreover, the new humans used their small wolves (volchata) to help hunt as well as using them to help carry the many kinds of things that the moderns used for their daily living and travel.

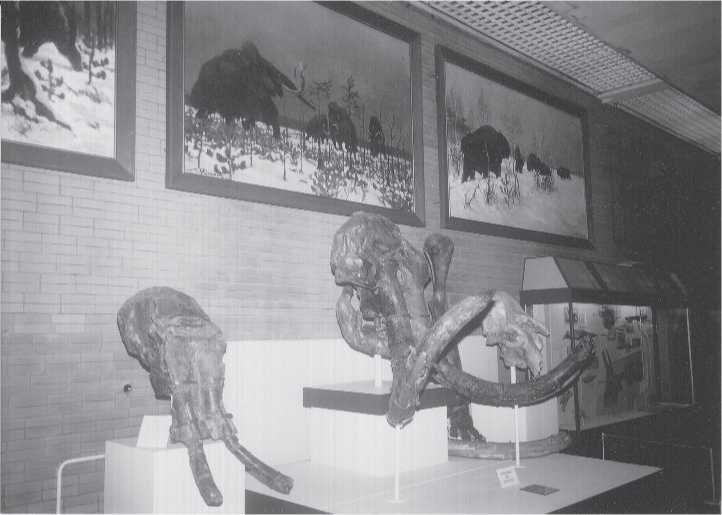

Fig. 1.23 Odyssey. Siberian mammoths. One of the many halls in the Paleontology Museum that range from the earliest fossil forms of life found in ancient Russia to Pleistocene megafauna as illustrated here. Mammoth fossils have been found all over Siberia in both paleontological and archaeological sites. Direct evidence of their having actually been hunted is very scarce (CGT color PIPM 6-8-01:11).

Old Long Clitoris’ shriveled and long-empty stomach pained her. Uncontrollably, she began to inch her way toward the cave entrance, getting so close that she could smell individual humans. They smelled like no other creatures because when they were very active their bodies would glisten with unpleasant-smelling moisture. She learned long ago that sweat was the hallmark of human odor, and humans tried to avoid sweating in the winter so that they would not freeze inside their protective clothing. Sweating was something that animals did who migrated from the south, so she thought that these humans originated from somewhere to the south. In fact, there were no humans known in the lands to the north where the sun disappeared for many weeks in the unbearable winter cold. Nor did her kind go to the northern edge of the land where all plant life was dwarfed and grew no higher than her foot.

Her cramping hunger drove her ever closer to the cave. Her movements were watched closely by her family, and they crept out stealthily from the birch stand toward the cave when they sensed from her upright ears that she was going to attack. When they were near, she rose to her full height; with her almost 100 kg weight she charged into the dim cave, followed only seconds later by the others. Instinct and experience told them to attack the smallest and youngest, or the crippled and elderly. Because they

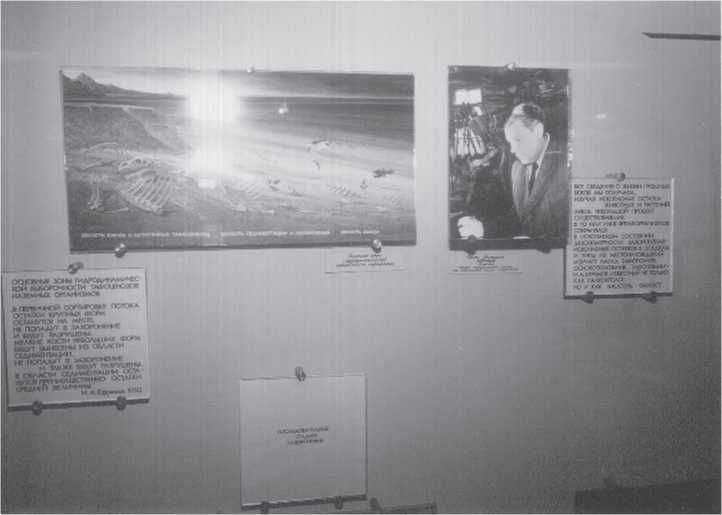

Fig. 1.24 Odyssey. Exhibit of Yefremov’s work. Strangely minimal and inconsistent with his worldwide fame, the inconspicuous exhibit is placed in a poorly lit first-floor corner. The captions read (Left): “Basic zones of hydrodynamic section. [sampling] of the taphocenoses of terrestrial organisms. In the primary sorting, the movement of large creatures will remain in situ. They will not go into the deposit and will be destroyed, small bones of smaller forms will be brought out of the sedimentation area; they will not get into the deposit and will be destroyed as well. The remains of middle-sized forms will predominantly stay. I. A. Yefremov 1950.” Center: “The sequence of stages of burial.” Right: “All the evidence about life in the past centuries we obtain through the study of fossil remains of animals and plants. Only a small amount of organisms, which lived at one or another time are preserved in the fossilized condition. The regularities (laws) of burying fossil remains in deposits and types of their location are the subject of taphonomic science. The founder of taphonomy is I. A. Yefremov, well known, not only as a paleontologist, but fiction writer, as well.” The small caption beneath Yefremov’s photograph reads: “Ivan Antonovich Yefremov, Professor, Awarded the Laureate for the Laboratory of Quadrupeds, Director” (CGT color PIPM 6-8-01:31).

Outnumbered the humans five to one, they easily grabbed the gazelle torso and pulled down two children by their heads. Amid the chaotic screams, cackling, barking, slashing teeth, and growls, an old woman was knocked to the ground, dropping the small bone tailoring needle she was using to repair a rip in a child’s boot. Two male hyenas tore her face off. In seconds, the hyenas dragged two young ones, the old woman, and the frozen gazelle to the darkening birch thicket where the pack tore the children and woman to pieces after they first eviscerated them alive. No humans or little wolves followed.

The hyenas had won another victory. Their feeding was total. No archaeologist in the future would ever learn of this event, nor of many other such events that left no traces of

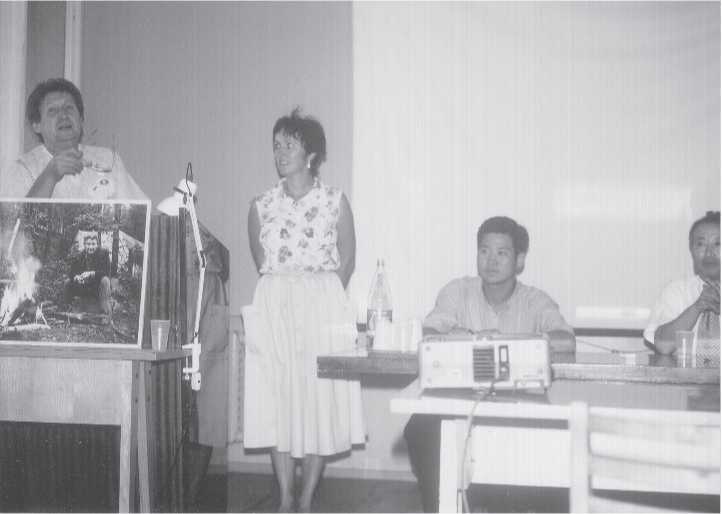

Fig. 1.25 Odyssey. Reporting scientific findings. lAE Director, Academician Anatoly P. Derevianko (left), presents the wrap-up of a paleoanthropological conference on “Pleistocene Paleoecology at the Kaminnaya Locality, Siberia, and Adjacent Territories,” held at the Institute in memory of Academician A. P. Okladnikov, first Director of the Institute (photo on podium). Translating for Derevianko is Elena Y. Pankeyeva (center). Present also are the final discussants, Heon-Jong Lee from Korea (second from right), and Gi-Kill Lee, also from Korea (right). The Siberian archaeologists and related earth scientists are almost compulsive in reporting their findings at these sorts of conferences, which unlike elsewhere are not based on formal membership in a particular scientific organization. As far as the senior author could learn, there are no formal organizations like the American Association of Physical Anthropologists or the Society of American Archaeology anywhere in Russia. Reporting of scientific accomplishments is driven by topical specialists such as Derevianko. We have reported our taphonomic research at a few conferences in Siberia (the senior author speaking, Olga Pavlova translating) (CGT color IAE 7-24-98:10).

The deadly competition between Siberian cave hyenas and humans. But vague clues to these events remained, and it is this book that attempts to tie these clues together into a larger story about Ice Age Siberia.

Next, we discuss the strange life of the author of taphonomy, and define and illustrate the criteria for our taphonomic observations.

World History

World History