Archaeology and Interpretive Art

During the past two decades, archaeologists, interpreters, and educators worldwide have increasingly collaborated to more effectively interpret archaeology and cultural heritage. Employing an interdisciplinary team approach, public interpretation practitioners use their knowledge and skills to create opportunities for the public to form intellectual and inspirational connections to the meanings and significance of the archaeological materials and the peoples who created them. Increasingly, they have come to appreciate the value and power of artistic expression in helping to convey archaeological information to the public and giving it new meaning. What we have termed ‘interpretive art’ has been used successfully in paintings, drawings, posters, teaching guides, reports, popular histories, and Web presentations as ways of engaging, informing, and inspiring the public about the value of archaeology. Interpretive message and associated meanings can be delivered through divergent artistic expressions such as two-dimensional oil paintings, three-dimensional exhibits, public sculpture, and popular history writing. Successful programs utilize techniques that both inform and entertain. The goals are to connect, engage, inform, and inspire, resulting in a lasting and enhanced appreciation of the resource (see Interpretation of Archaeology for the Public; Popular Culture and Archaeology).

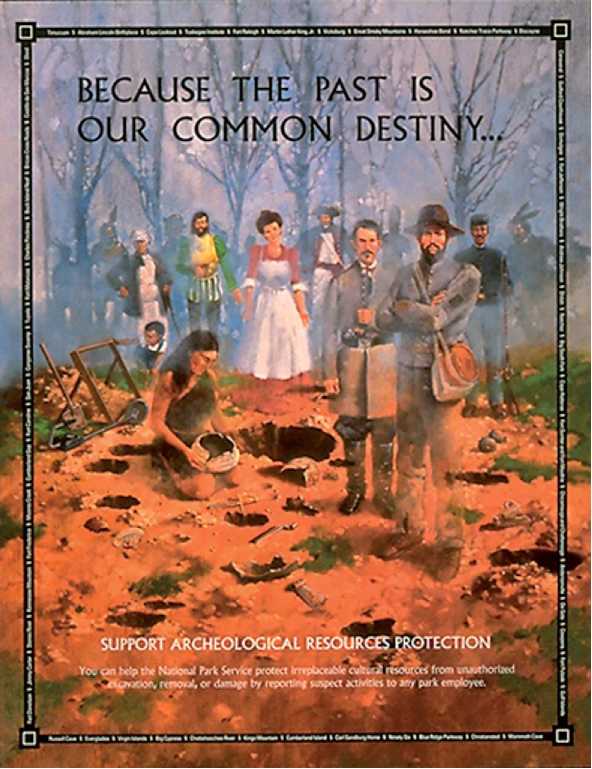

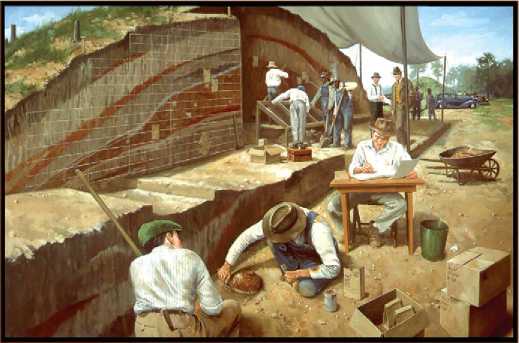

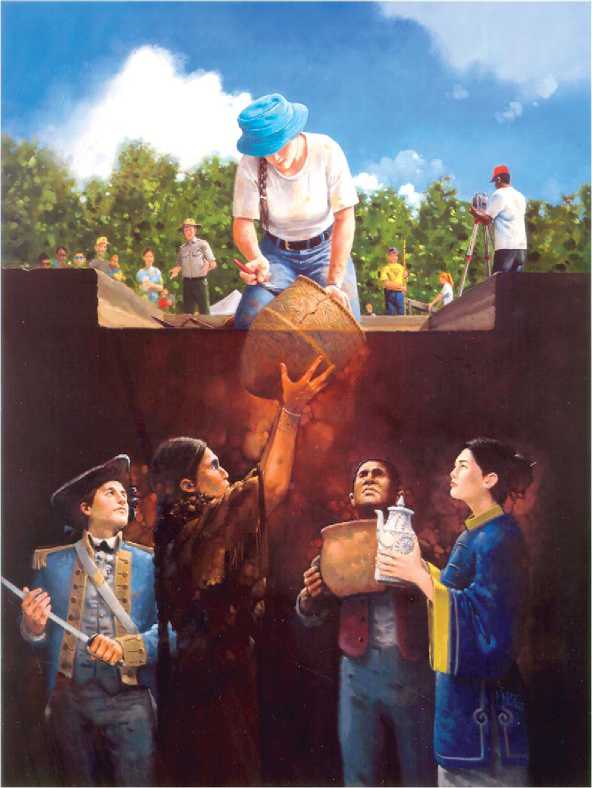

At the Southeast Archeological Center in Tallahassee, Florida, in our outreach and public interpretation efforts, we have enlisted painters and writers to produce artistic works with the goals of complementing and helping to explain the archaeological record, while also engaging, entertaining, and inspiring the audience. We believe that our interpretive oil paintings also help dispel false or stereotypic imagery by offering an alternative, more plausible scene. Estheti-cally pleasing paintings can attract and engage while also serving a number of other interpretive objectives such as supplying detailed information about the resource and carrying conservation, commemorative, or metaphorical messages (Figures 1-3).

Some parallels to this team-oriented interpretive strategy can be drawn from recent developments in the realm of the so-called ‘dinosaur art’ where the expert palaeontologists have learned to work cooperatively with dinosaur artists - to work with the artists rather than to dismiss what the experts perceive as inaccurate depictions stemming from the public’s fascination with these fantastically large, powerful, and grotesque creatures. As with archaeology, the public’s attraction to dinosaurs does not usually spring from a scientific source. The palaeontologist’s inability to say what dinosaurs really looked like has no power to drive away inaccurate icons. Media-Savvy palaeontologists have learned to wait to publicize a dinosaur discovery until they have a commissioned painting of the creature to show. They have learned that, by working with the artist, the experts can at least inform the public about what is known. The artists usually want to be as accurate as possible because doing so lends credence and prestige to their work. Most dinosaur images today, including those depicted in television and movies, are guided by hard data, though hard data can only be a starting point. We believe that archaeologists should likewise take advantage of the public’s natural curiosity in working with artists to create images grounded in hard data - announcing new discoveries and new interpretations - even if this is just a starting point, as with dinosaur art.

History well told makes a compelling story. In producing popular accounts rooted in historical and archaeological research, we have partnered with artists and writers to produce works that reflect dramatic and skillful writing as well as accurate information. Popular

Figure 1 Example of interpretive art for a public awareness poster with a conservation/protection message. Courtesy, Southeast Archaeological Center, National Park Service. Oil painting by Martin Pate.

Figure 2 Example of interpretive art used in a commemorative poster for the 50th anniversary of the Southeast Archaeological Conference. Courtesy, Southeast Archaeological Center, National Park Service. Oil painting by Martin Pate.

Figure 3 Example of interpretive art with a metaphorical message about historical archaeology and the components of research, coupled with public interpretation. Courtesy, Southeast Archaeological Center, National Park Service. Oil painting by Martin Pate.

Writers of cultural resource themes can tell stories inspired by archaeology that are appealing because of the nature of the material and because of the way the story is told. They are interpreters who contribute not only to the esthetic expressions of art, but also to human understanding and increased knowledge.

Stories well done are stories that reveal how people and societies have actually functioned. They prompt thoughts about the human experience in other times and places. These esthetic and humanistic expressions about cultural history inspire us to immerse ourselves in efforts to reconstruct more distant pasts, exploring the ways people constructed their lives. This evokes in us a sense of beauty and excitement and gives us added and enhanced perspectives on cultural history, society, and the human condition. For example, in preparing the highly demanded and award-winning popular history Beneath These Waters, the National Park Service chose a team of professional writers adept at the art of effectively translating technical information for the lay public. Contract writers Sharyn Kane and Richard Keeton, because they were not formally trained archaeologists or historians and were unfamiliar with the world of government contracting, overcame some distinct disadvantages in accomplishing the task of writing this book. Guided by a scope of work and in collaboration with government archaeologists, the authors’ task was to take the results of two decades of research from the multivolume Richard B. Russell Reservoir cultural resources studies, strip them down to the essentials, and reclothe them in a fashion that would be well received by general, but diverse, audiences without losing the fundamental integrity and accuracy of the original, research-derived material.

Utilitarian versus Esthetic in Archaeological Public Interpretation

Public interpretation of archaeology involves methodologies associated with conveying factual and stimulating explanatory information to the lay public. The popularity of its products and programs reflects a growing public awareness of the importance of archaeology and the ways in which the past is represented, including the inherent value of understanding imagery both ‘from’ and ‘of’ the past.

Art is something created by humans that is evocative; it is more than symbolism or simple representation. It causes the viewer to feel something: anger, joy, sadness, fear, energy, violence, tranquility, loneliness, and awe. It causes the viewer to think. It makes a social or cultural statement. It makes us see humor where we have not seen it before. It places us in settings and moods that we have not yet encountered. It allows us to experience something in a new way. It is much more and different than mimicry. Art can do many things to us at the same time.

An artist shows imaginative skill in arrangement or execution. Rendering an esthetically pleasing effect is the rendering of an altered nature or an altered material world. Aristotle in the fourth century BC wrote that this modification of nature and objects produces two types of art: utilitarian art that is necessary for life; and pleasurable or esthetic art that is produced for recreation. Art in the latter sense is the conscious use of skill and creative imagination in the production of esthetic objects. But the classification of objects as art is cultural, subjective, and at times, controversial.

Archaeologists, both historians and prehistorians, have had a long-standing interest in art and the relationships of archaeology and art. Today, we can find university curricula that teach archaeological approaches to the study of art which are distinct from those of the other disciplines that study art. Here, ‘archaeology of art’ takes an anthropological approach that often challenges Eurocentric and traditional Western interpretations. Archaeologists are increasingly examining how archaeological information is communicated in national parks and museums; by popular literature, film, television, music, and various multimedia formats; and its overall effectiveness. We want to explore the potential of cognitive imagery that springs from an association with archaeology and its attempts to reconstruct past lifeways. We want to know how certain interpretive methodologies, in various settings, using certain media formats, can contribute to both public and professional understanding of human history.

Esthetic art has been in our own culture and in cultures around the world since recorded history, yet archaeologists rarely ask questions about esthetics in their research designs, but rather have concentrated on the utilitarian explanations. Although the esthetic qualities of things are sometimes acknowledged in the archaeological literature, they are rarely discussed. This strategy has not only been convenient, but perhaps partially justified if one assumes, as some have, that the purpose for esthetic art is lost with an unrecorded culture. But, if only unsatisfactory utilitarian reasons can be found to justify an artifact and its attributes, then the motive for its being or creation must be esthetic. Perhaps it is time for archaeologists to more earnestly address and relate to esthetic art forms that have been as important in all cultures as ways of showing imaginative skills. We pose the question: might an emphasis on esthetic qualities also be an important element in the interpretation of the past? Perhaps more accurate interpretations would be rendered, and apparent theoretical contradictions in the archaeological record explained, if the esthetic arts were more fully considered.

Palaeoarchaeologists have long been at a loss, beyond utilitarianism, to explain the remarkable skill levels and apparent ‘artistic’ attributes in many varieties of Palaeo-Indian creations, including cave paintings and projectile points and tools. Baker (1997) has pointed out that the knowable dimensions of a given culture are inversely proportional to its remoteness in time. More hard data is available as we come to more recent time periods and thus a less speculative starting point for the interpretive artist as well as the technical experts. As a result, it is difficult for an archaeologist to define or differentiate between utilitarian and esthetic art forms in ancient cultures. The Palaeolithic cave paintings in southern France were created over 30 000 years ago. However, the lack of knowledge of the culture seriously impedes the archaeologist from defining functional aspects of these images. In contrast, the Folsom projectile point manufactured approximately 10 000 years ago in North America has the obvious utilitarian art form of piercing and cutting in the food gathering process. With a paucity of observable material culture, are we left only with subjective or logical explanations? Do the ‘flutes’ on the Palaeo-Indian projectile represent a pleasurable or esthetic art form in addition to its utilitarian function? Those of us familiar with Palaeo-Indian traditions often do not consider these examples of stone craftsmanship to be works of esthetic art. Others, however, speculate that they may represent some kind of ceremonial function, possibly within the realm of magic or religion. But these are vague speculations at best. We suspect that some utilitarian objects through time and culture change are embellished or elaborated, sometimes to a point where the original utilitarian forms are barely, if at all, recognizable. We observe what appears to be a combining or blending of esthetic and utilitarian attributes, and this combination has occurred across all time lines.

World History

World History