1 Provenience. For this book we examined and re-examined the Razboinich’ya faunal collection during 1998, 1999, 2000, and 2003 (Table A1.1, site 21). It is our preeminent baseline assemblage for identifying the bone damage signature of late Pleistocene Siberian carnivores. Excluding the modern Russian surface trash found near the cave entrance, we found few differences in the assemblage regardless of vertical stratigraphy or horizontal location; hence, all the faunal remains have been pooled. The deposits span a period of perhaps 40 000 radiocarbon years. Some of the lack of stratigraphic difference is presumably due to the digging behavior common to hyenas of today (see Chapter 4). Altogether we scored 739 pieces out of thousands that were either too small or were undamaged whole bones of complete small animals that probably died of natural causes within the cave. This total is 7.9% of the grand total for our multiple sites.

2 Species. Of 638 pieces larger than 2.5 cm assessed for species, those that could not be identified even in a general way were the most fTequent (45.1%), followed by fox (31.0%), hyena (11.7%) (Figs. 3.115-3.116), and wolf (4.7%) (Table A1.2, site 21). The high frequency of fox probably represents natural deaths within the cave, because most of these bones and teeth have very little perimortem damage. Had these foxes been carried into the cave as hyena kills, we feel that their perimortem condition would have exhibited much more damage, if not in fact having been almost totally destroyed due to the light and delicate nature of the fox skeleton. Species represented at about 1.0% include bear, big mammal, bird, and goat-sheep. Compared to the unweighted averages for all our assemblages, Razboinich’ya seems meaningfully below average for big mammal, bison, goat-sheep, horse, mammoth, and above average for fox, wolf, and indeterminable. Wolves may have also denned in the cave when vacated by hyenas. Indeterminacy of species undoubtedly reflects both small piece size and the powerful destructiveness of hyena jaws and teeth.

3 Skeletal elements. There were 638 pieces studied for skeletal element identification (Table A1.3, site 21). Of those represented by about 5.0% or more, the semi-specific category of long bone was most frequent (26.0%). This was followed by rib (10.2%), vertebra (8.3%), indeterminable (5.6%), penis (5.4%), mandible (4.7%), and humerus (4.7%). With one exception, none of these values, nor the others of lower percentage, are noteworthy when compared to the total in our other site assemblages. The exception is the penis bone. This skeletal element is absent in all but three of our other assemblages, and in each of these the frequency is less than 1.0%. We can think of no explanation for the relatively high Razboinich’ ya penis bone occurrence.

4 Age. Of the 638 Razboinich’ya pieces scored for age, adults were more frequently identified (52.5%) than sub-adults (7.4%) (Table A1.4, site 21). Compared with our other assemblages, there is nothing out of the ordinary in these values. Pieces whose age could not be determined (40.1%) were similarly unexceptional, although twice as common as the mean for all sites combined.

5 Completeness (Fig. 3.117). Of the 638 Razboinich’ya pieces scored for completeness (Table A1.5, site 21), those that lacked both anatomical ends were the most common (62.8%). Those with one anatomical end were next most frequent (28.5%), and whole

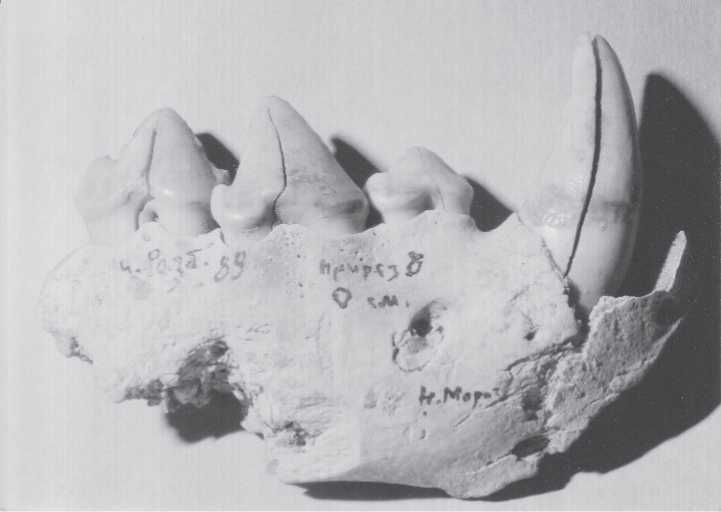

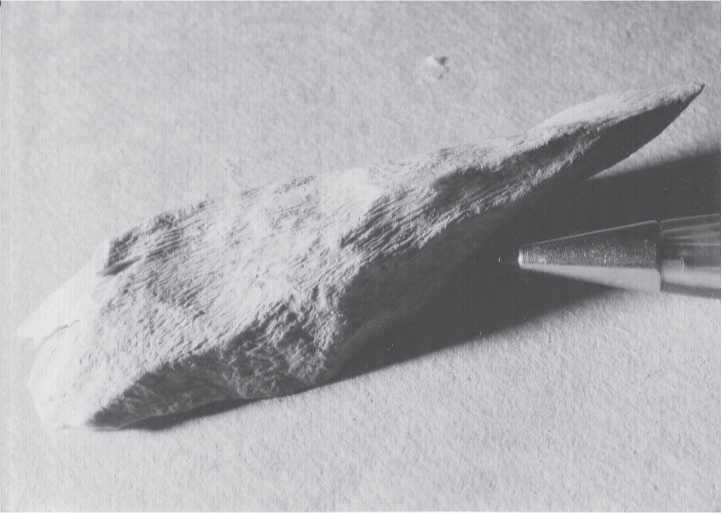

Fig. 3.115 Razboinich’ya Cave, hyena (1989). A 10 cm long fragment of the right side of a lower jaw that belonged to a young occupant shows shearing and puncturing damage, which signals cannibalism. The tooth dint beneath the first post-canine tooth has small embedded bone fragments. (CGT neg. IAE 7-28-99:32).

Fig. 3.116 Razboinich’ya Cave, hyena (1988). Another young cannibalized cave occupant. This right

Side mandibular fragment is 10.1 cm in length (CGT neg. IAE 7-28-99:36).

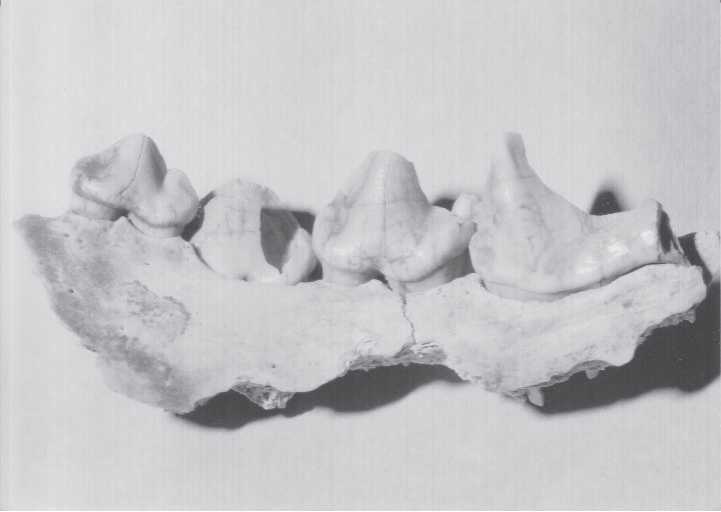

Fig. 3.117 Razboinich’ya Cave, unsorted deposit. A sense of the cave’s contents can be gotten from

This view of yet-to-be-studied bones, teeth, and hyena coprolites recovered by Ovodov in 1989. Two round, white coprolites are in the lower left corner. The match boxes are 5.0 cm in length and contain tiny teeth and bones. The pencil points to a hyena canine with tooth scratches on its root (CGT neg. IAE 7-6-00:1).

Bones were least frequent (8.6%). None of these values are exceptional compared with the other 28 assemblages, being as they are fairly close to the means for each condition in the pooled 30-site assemblage.

6 Maximum size. The mean and related statistical values were calculated on the basis of 599 measured pieces that were for the most part greater than 2.5 cm in length of maximal dimension (Table A1.6, site 21). Although there are some statistically significant differences between the ordinal values of the Razboinich’ya pieces when compared with other assemblages, such as Mal’ta and Shestakovo, these significant differences are due solely to the latter two sites having some very large pieces of mammoth bone that produce much larger means and related statistics. On the whole, the Razboinich’ya mean (6.5 cm) and range (2.4 cm to 24.4 cm) has no exceptional size differences with most of the other faunal assemblages. Nor does it differ in any meaningful way fTom the pooled assemblage averages. Compared with the lengths of undamaged long bones of fox, hyena, and wolf provided by Vera Gromova (1950: table 27), the Razboinich’ya upper range limit (24.4 cm) is greater than all five fox long bones, and about the same as those of the hyena and wolf. The lower range limit of Razboinich’ya is, of course, much smaller than those of these species.

7 Damage shape. We assessed the type of damage in 739 pieces. The forms most common are fragments (31.1%), medial rib pieces (15.4%), and flakes (13.4%). Because of the many fragments and flakes in the Razboinich’ya assemblage, the majority of the other damage types, such as “mostly whole,” have lower frequencies than the pooled averages. Compared with the pooled averages, the Razboinich’ya assemblage shows more overall damage and processing.

8 Color. We could evaluate color in 637 Razboinich’ya pieces (Table A1.8, site 21). Most pieces are ivory colored (92.9%), with some brown (6.4%) and white (0.6%) examples. These values are not much different fTom the pooled averages, but differ greatly from the open sites like Ust-Kova. Black mineral “flowers” (see Fig. 3.170) occurred on 35 ivory colored Razboinich’ya pieces. We have not found any explanation for how these deposits are formed.

9 Preservation. In total, 625 pieces were assessed for quality of preservation (Table A1.9, site 21). Most Razboinich’ya pieces are ivory hard (93.8%). A much smaller number (6.2%) are chalky. These values indicate significantly better preservation at Razboinich’ya than in the pooled assemblage, although there are individual cave sites such as Kaminnaya with even better preservation. Because of the cave’s excellent preservation conditions, we presume the chalky pieces represent old surface-weathered bones that hyenas carried into the cave.

10 Perimortem breakage. Of 607 pieces, Razboinich’ya has identifiable perimortem breakage in 92.4% (Table A1.10, site 21). This value is more than that of the pooled assemblage. While representing a great deal of bone breakage by carnivores, there are a few archaeological sites with even higher values of perimortem breakage, including Bolshoi Yakor and Varvarina Gora.

11 Postmortem breakage. Postmortem breakage was found in 10.9% of 607 Razboinich’ya pieces (Table A1.11, site 21). Much of the damage was caused by the difficulty of archaeological recovery in the pitch-black cave, and in subsequent handling and transport down the mountain and later in the laboratory. Although one-tenth of all pieces show some postmortem damage, the amount is less than the average for the pooled assemblages, and is therefore unexceptional.

12 End-hollowing. This damage form is distinctive of carnivores, especially when there are co-occurring tooth dints and tooth scratches. End-hollowing was found in 8.1% of 543 Razboinich’ya pieces (Table A1.12, site 21). The Razboinich’ya frequency is nearly the same as that of the pooled assemblage. Although we expected to find end-hollowing in sites with carnivore remains, we did not know how much to expect. Nor did we expect to see as much end-hollowing in archaeological sites as actually occurred in a few sites, such as Okladinov and Ust-Kan Caves. These two caves, as well as others, must have had a significant carnivore presence from time to time. Nevertheless, most of the archaeological sites have much less end-hollowing than does Razboinich’ya. It seems reasonable to propose that late Pleistocene sites in Siberia exhibiting 5-10% or more end-hollowing should be considered as having had a significant carnivore presence. We will discuss this proposition in more detail in Chapter 4.

13 Notching. Of 618 pieces, Razboinich’ya has 23.6% with notching (Table A1.13, site 21). While this value is greater than the average for the pooled assemblage, it is generally like the values found in other paleontological sites. It is greater than occurs in the archaeological sites, with the exception of Okladnikov Cave. Most of the Razboinich’ya pieces with notching have only one notch (76.4%). While there are no Razboinich’ya pieces with more than six notches, notching nevertheless seems to be a characteristic of sites with definite carnivore presence, especially that of hyenas.

14 Tooth scratches (Fig. 3.118). Razboinich’ya has a high frequency of pieces with tooth scratches. In 661 pieces, 37.1% have one or more scratches. This value is almost twice that of the pooled assemblage, and much like that of our other paleontological sites (Table A1.14, site 21). There are several Razboinich’ya pieces with multiple scratches; one piece had 50 scratches. If we assume that 30-40% tooth scratching is evidence of a significant carnivore contribution to the perimortem taphonomy of a site, then, once again, Okladnikov Cave would appear to have been used by carnivores as much as by humans.

15 Tooth dints (Fig. 3.119). Like the three previous variables, Razboinich’ya shows that tooth dints, as well as scratches, are also a useful indicator of carnivore presence. More than half (52.8%) of 629 Razboinich’ya pieces have one or more tooth dints (Table A1.15, site 21). This value is similar to that of our other paleontological sites. It is greater than the average for the pooled assemblage. There are several Razboinich’ya pieces with multiple dints; 14.0% have more than seven dints. As noted previously, pieces showing tooth dinting are very common at Okladnikov Cave.

16 Pseudo-cuts. We examined 638 Razboinich’ya pieces for pseudo-cuts, finding them expressed in 3.1% of pieces (Table A1.16, site 21). This value is slightly less than the average for the pooled assemblage (4.8%). Most of the Razboinich’ya pieces with pseudo-cuts have only one, but a very small fraction (0.2%) have more than seven. Several of our sites have pseudo-cuts. Paleontological sites have the most, but the Denisova archaeological site has the greatest amount (28.6%). We suspect a sampling error for Denisova, although observation error is possible because we studied the Denisova assemblage in the field and not under more ideal laboratory conditions.

17 Abrasions. Abrasions are rare in all of our assemblages, although they are slightly more common in the archaeological than in the paleontological sites. Of 623 Razboinich’ya pieces, we identified only 0.5% with abrasions (Table A1.17, site 21). This is less than the average for the pooled assemblage, as might be expected since abrasions are believed to have been caused mainly by bone slippage on a gritty stone surface such as that of a hammer or anvil stone. A grainy limestone cave floor could also have caused trampling abrasions, although much more finely and with fewer lines than those resulting fTom the glancing impact of stone tools or slippage on a stone anvil.

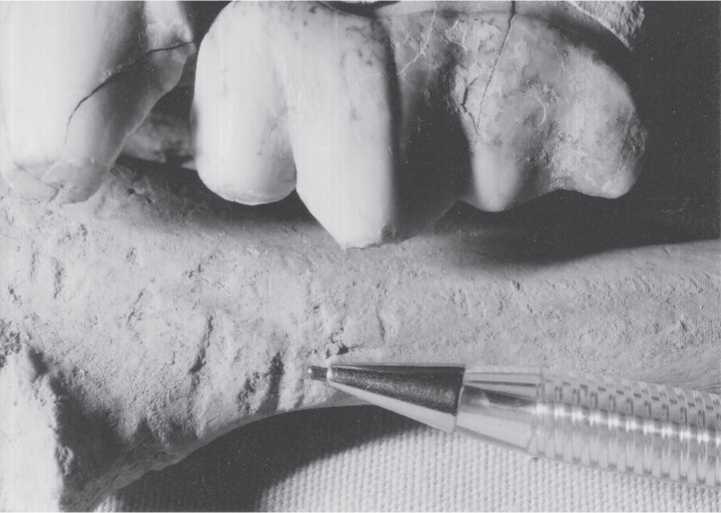

Fig. 3.118 Razboinich’ya Cave, bone damage. The pencil points to tooth scratches on a hyena ulna.

A hyena jaw has been placed at the top to show the burin-like form of the chipped cusp tip above the pencil. It is these chisel-like cusp tips that we believe caused the pseudo-cutting (CGT neg. IAE 7-6-00:4).

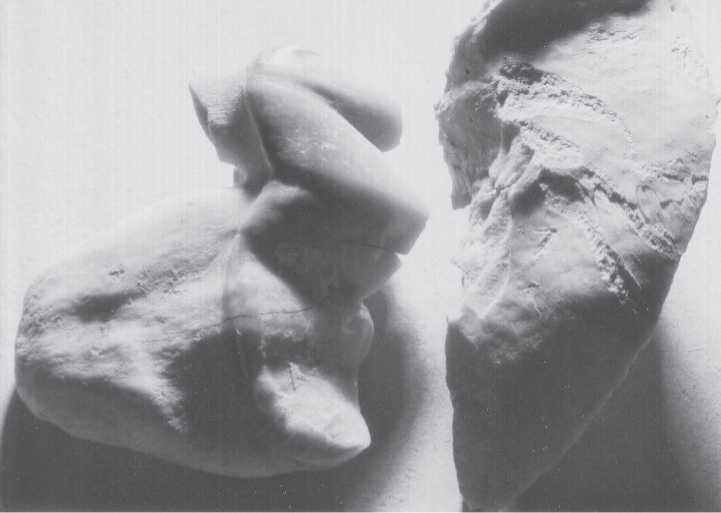

Fig. 3.119 Razboinich’ya Cave, tooth damage. Arrows point to tooth dints on the roots of two hyena teeth,

Both dints being near the crown-root border. Cannibalism is suggested. Note also the area of developmentally defective enamel on the upper tooth in the upper right corner of the photograph (CGT neg. IAE 7-6-00:5).

Fig. 3.120 Razboinich’ya Cave, bone damage. On the right is a hyena cranial fragment with wide tooth

Scratches. A hyena molar fTom the same excavation unit is placed near to illustrate how the worn cusps could have scratched the bone in a chisel-like fashion (CGT neg. IAE 8-3-99:18).

Fig. 3.121 Razboinich’ya Cave, hyena teeth. Worn and burinized tips of maxillary teeth (CGT neg.

IAE 7-6-00:14).

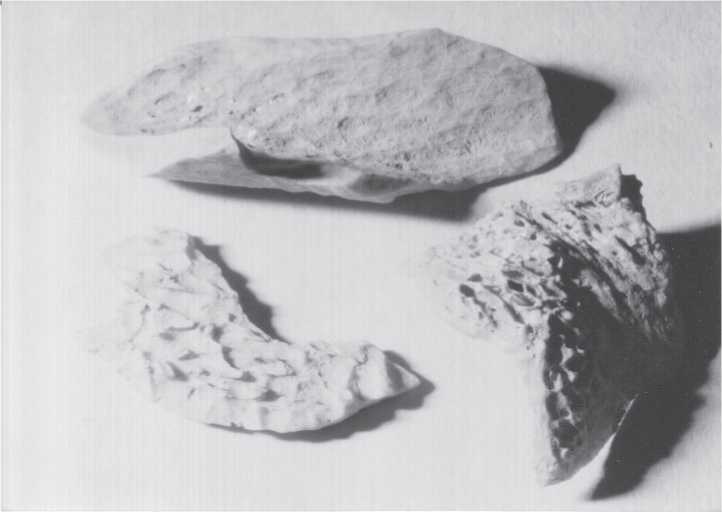

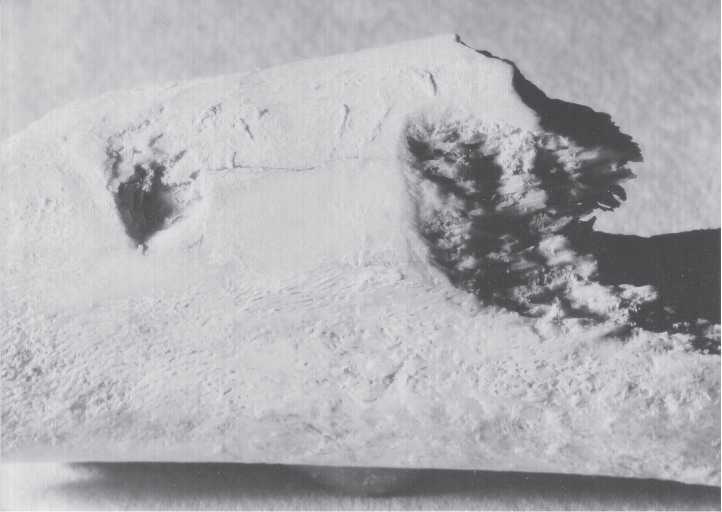

Fig. 3.122 Razboinich’ya Cave, stomach bones. These specimens from the 1977 excavation season were

Found 15 m fTom the entrance, along with other cave midden. The largest piece is 4.8 cm in length (CGT neg. IAE 7-28-99:28).

The number of abrasion grooves or lines ranges from one to more than seven in the Razboinich’ya assemblage.

18 Polishing. We originally assumed that polishing would be more common in sites with carnivore presence than in archaeological contexts. Razboinich’ ya and several other assemblages showed this assumption to be incorrect. Out of 598 Razboinich’ya pieces, fully 40.6% had no identifiable polishing (Table A1.18, site 21). We further assumed that polishing due to carnivore chewing would occur more frequently on both the end and the middle of a piece than would be the case in an archaeological assemblage. Razboinich’ya has only 27.1% of its pieces with polishing on the middle and one or both ends, compared with the 45.1% average for the pooled assemblage or archaeological sites such as Kamenka (61.3%) or Varvarina Gora (71.2%). However, very heavily polished and highly rounded pieces are impressionistically far more common in paleontological than in archaeological sites. Unfortunately, we failed to make systematic observations on very heavy polishing, so we cannot provide any quantitative information on this perimortem taphonomic condition.

19 Embedded fragments. We examined 611 Razboinich’ya pieces for embedded fragments, finding 8.8% (Table A1.19, site 21). This is about twice as many as in the pooled assemblage (4.1%). The Razboinich’ya frequency is generally greater than we found for

Fig. 3.123 Razboinich’ya Cave, stomach bone. This specimen is 6.1 cm long and 1.8 cm wide, which is larger

Than the diameter of most of the hyena coprolites ITom this cave (CGT neg. IAE 7-28-99:8).

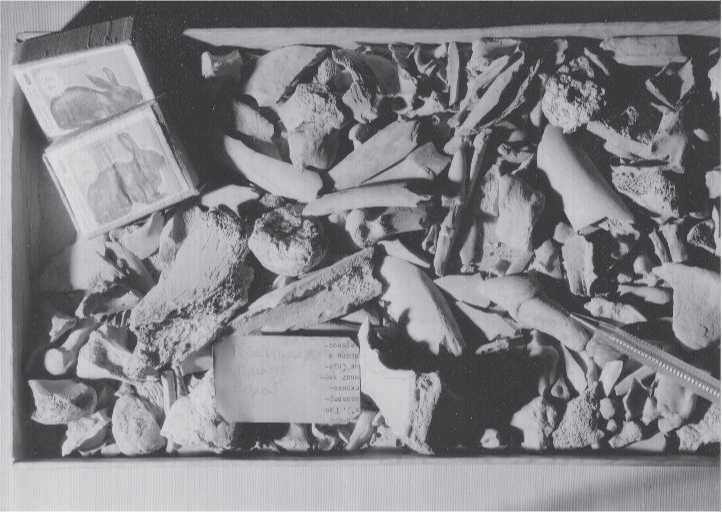

Fig. 3.124 Razboinich’ya Cave, bone damage. An unstudied 1986 collection of bones, teeth, and coprolites that illustrate the size and variety in the cave hyena-age deposits. The earliest deposits in the cave are sterile. The oldest animal remains Ovodov found were those of foxes. Sometime later, hyenas started to use the cave, and did so until near the end of the Pleistocene (CGT neg. IAE 7-29-98:34A).

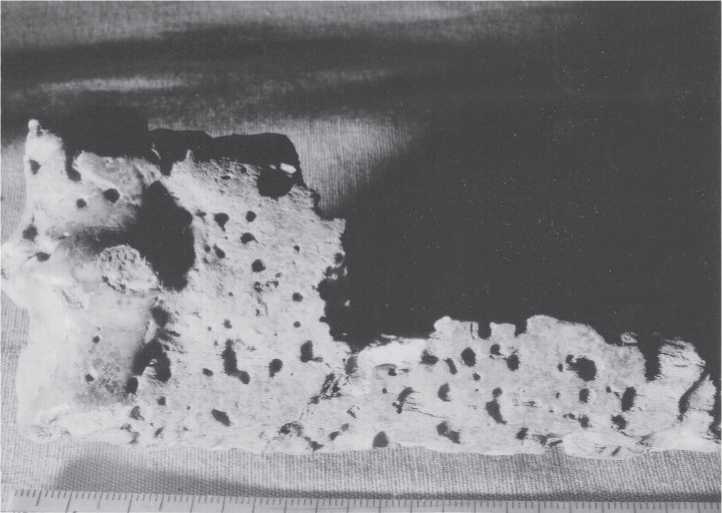

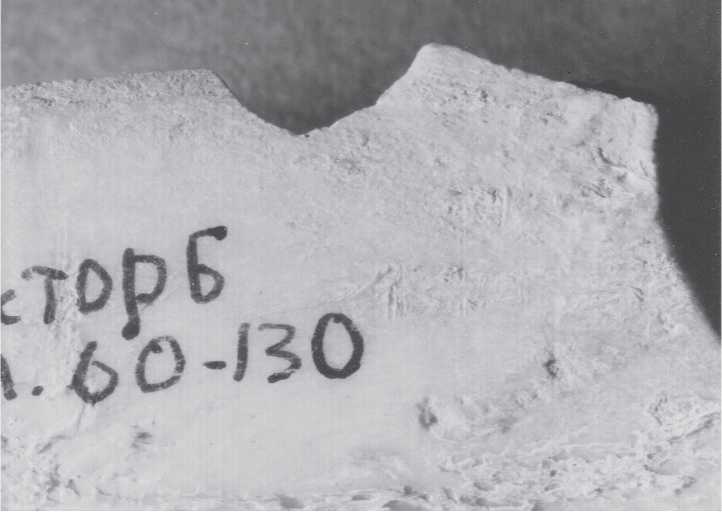

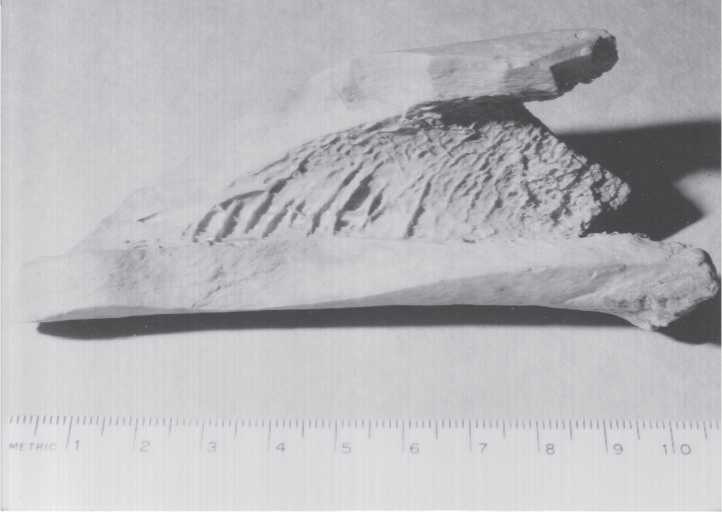

Fig. 3.125 Razboinich’ya Cave, bone damage. The cause of this unusual pitting damage is unknown.

Possibilities that come to mind include insect burrowing (like wood-boring bark beetles), digestive erosion (but the surface is hardly eroded and bone size is too large), and bone cancer. Pitting has ragged borders. Found at a depth of 60 cm. Scale is in centimeters (CGT neg. IAE 7-6-00:19).

The archaeological sites such as Denisova (1.2%), Kaminnaya (2.9%), Ust-Kan (1.1%), but not Ust-Kova (9.5%). Embedded fragments occur slightly more often in most of the paleontological sites. One embedded fragment per piece (5.7%) is the most common condition in the Razboinich’ya assemblage. Five fragments per piece is the largest number occurring in the Razboinich’ya series. These were found in only 0.6% of pieces with embedded fragments.

20 Tooth wear (Figs. 3.120-3.121). Only 25 Razboinich’ya pieces were scored for tooth wear, and generally fewer were scored for almost all of the other sites, making this variable quantitatively weak. Nevertheless, about one-third of the Razboinich’ya teeth indicated young individuals, which is close to the average for the pooled assemblage.

21 Acid erosion (Figs. 3.122-3.123). This perimortem taphonomic condition may well be the hallmark of carnivore bone processing, especially that done by hyenas. Our examination for acid erosion in 370 Razboinich’ya pieces turned up 7.3% (Table A1.21, site 21), a value close to the average for the pooled assemblage. On the basis of Razboinich’ya Cave, we propose that a frequency of 5-10% acid-eroded pieces indicates the presence of carnivores, especially cave hyenas. Hence, archaeological

Fig. 3.126 Razboinich’ya Cave, bone damage. Magnification of Fig. 3.125. Here, it can be seen that some of the

Pits have a basin or container shape. The senior author with others studied one prehistoric Alaskan complete human skeleton with similar but less pitting, concluding that the individual had suffered fTom multiple myeloma, a form of cancer. Width of image is 3.3 cm (CGT neg. IAE 7-6-00:23).

Fig. 3.127 Razboinich’ya Cave, bone damage. Rib fragment (1980, 2 m deep) with two large tooth dints, each 4x5 mm in diameter. Tiny bone fragments are embedded in the left dint (CGT neg. IAE 7-28-99:16).

Fig. 3.128 Razboinich’ya Cave, bone damage. Tooth notches on fracture lines. Actual width of image is

3.3 cm. This figure illustrates that notches are not always attributable to human bone smashing (CGT neg. IAE 7-28-99:2).

Fig. 3.129 Razboinich’ya Cave, bone damage. Tooth notch on fracture line. Notch is 1.0 cm wide. Tooth dints

Are also present, near bottom of photograph (CGT neg. IAE 7-28-99:19).

Fig. 3.130 Razboinich’ya Cave, bone damage. Tooth notch on opposite surface of Fig. 3.129 (CGT

Neg. IAE 7-28-99:18).

Fig. 3.131 Razboinich’ya Cave, bone damage. Pseudo-cut (at arrow). Actual width of image is 3.3 cm (CGT neg. IAE 7-6-00:7).

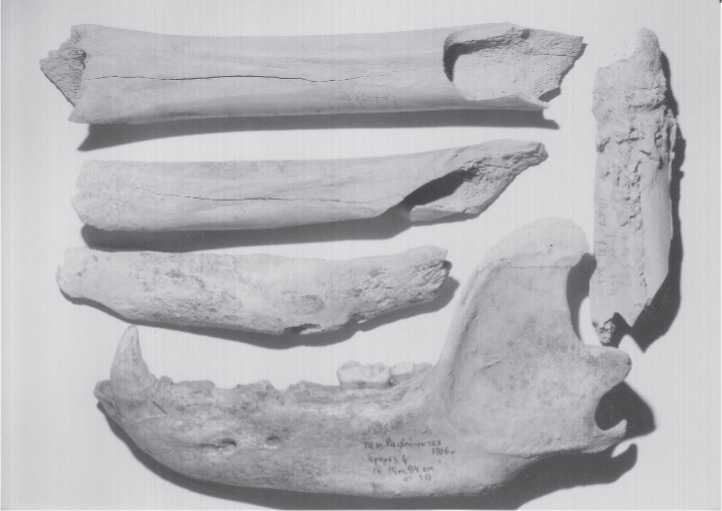

Fig. 3.132 Razboinich’ya Cave, bears. Ovodov and associates found bones and teeth of brown bears, which had been damaged by hyenas, randomly distributed in the cave deposits. The pieces shown here belonged to more than one animal. Ovodov suggests that bears wintered in the cave. Once they were asleep, the hyena occupants killed and ate them. Note spiral fracturing on right end of pieces second fTom the top. Jaw is 26.0 cm in length (CGT neg. IAE 7-23-98:30).

Fig. 3.133 Razboinich’ya Cave, bear. Spiral fracturing of this bear humerus was done by a hyena. The piece is 10.8 cm in length (CGT neg. IAE 7-28-99:25).

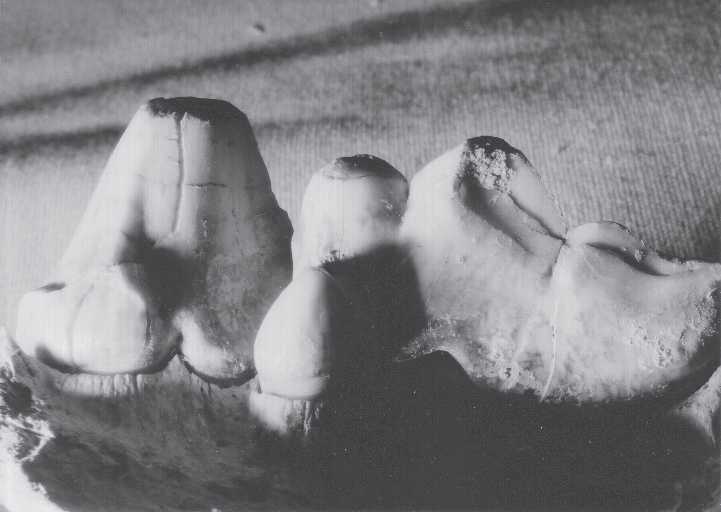

Fig. 3.134 Razboinich’ya Cave, bear. The maxillary teeth show relatively little wear, although the large

Molar has enamel breakage near its distal end (far right). That tooth is 3.7 cm in length. In contrast to the shearing teeth of hyenas, the bear dentition is better suited for milling, one of several reasons we feel that much of the bone breakage in this study was done by hyenas (CGT neg. IAE 7-8-02:22A).

Sites such as Kaminnaya, Okladnikov, and Ust-Kan should be viewed as having also been paleontological sites. As such, stratigraphic disturbances may have been severe (Fig. 3.124).

22 Rodent gnawing. Only 0.8% of 611 Razboinich’ya pieces had gnawing incisions. This is nearly the same as the average for the pooled assemblage (0.5%). Rodents were not a meaningful source of perimortem damage in nearly all of our assemblages.

23 Insect damage. There was no identifiable damage done by insects in 611 Razboinich’ya pieces, which corresponds to the total or near-total absence in all of our assemblages.

24 Human bone. No human bones or teeth were found in Razboinich’ya Cave.

25 Cut marks. None of 611 Razboinich’ya pieces had cut marks. This is strong supporting evidence for our inference that Paleolithic humans rarely used the cave in Pleistocene times. As mentioned previously, only on the modern cave floor near the entrance are there any indications of relatively long-term human use of the cave. This evidence includes a fire hearth, cooking refuse, and three pieces of bone with cut marks, one of which was also burned.

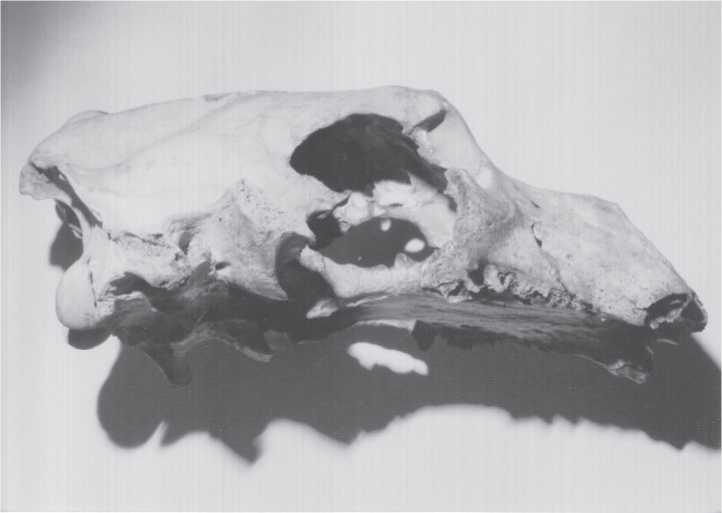

Fig. 3.135 Razboinich’ya Cave, bear skull, lateral view. Ovodov and associates made a remarkable

Discovery in 1990. Deep in the cave they found the possible burial ofa brown bear skull in Layer 2. This skull of an old edentulous bear with partly healed antemortem snout wounds also had massive perimortem breakage to the right side of its head, behind the right eye and zygomatic process. The damage appears traumatic, like the impact from a blunt weapon. There is no sign of healing or infection on any of the perimortem fractures. Most surprisingly, there is no identifiable carnivore damage. Ovodov proposes that the skull was placed in the cave by humans, possibly the Mousterian inhabitants of Kaminnaya Cave, down below the mountain and an hour away. Skull is 40 cm in length (CGT neg. IAE 7-23-98:25).

26 Chop marks. As with cut marks, the only Razboinich’ya piece out of 611 is a midtwentieth-century bone with a single chop mark. There are a few damaged pieces that do not exactly fit our trait definitions (Figs. 3.125-3.131).

World History

World History