West and Central Africa contributed large numbers of enslaved Africans to the trans-Atlantic trade. Even before Columbus’ visit to the New World and European migrations that followed in search of greener pastures, African slaves had been taken to Spain and Portugal from northern Africa, consequently becoming a major factor in the trade that drove Europe and the Americas to prosperity. The development of plantations in the mid-fifteenth century on the West African coast was

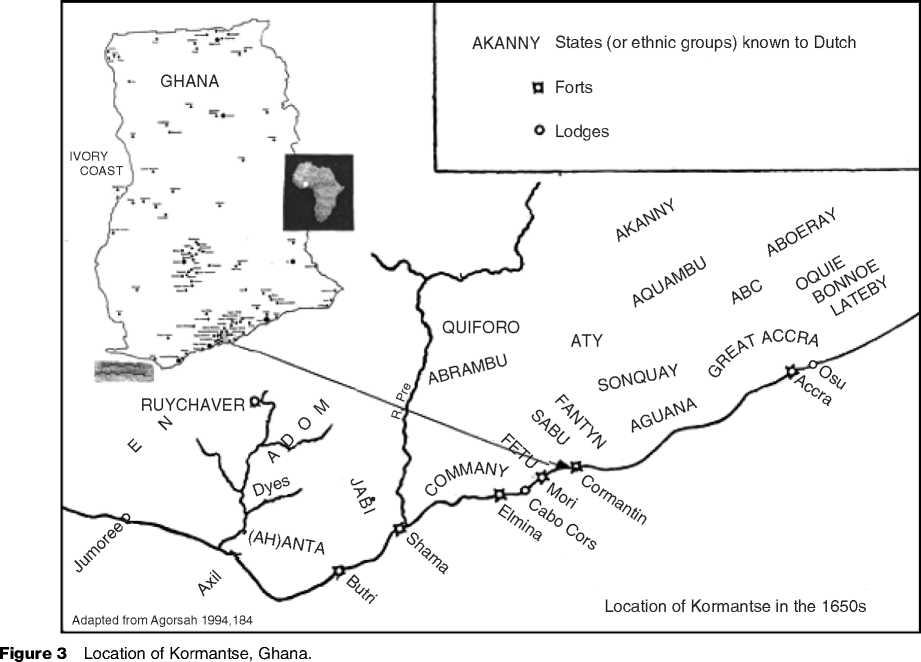

Eventually switched to the Caribbean and the Americas in a confusing trade that makes tracing of the origin of the enslaved Africans increasingly difficult and elusive. Identifying cultural transfers, the nature of the pre-existing cultural traits among groups that served as the carriers of the original substantive aspects of the cultures, and the reconstruction of their formation and transformation processes became more difficult. Meanwhile, the early approaches designed to recover artifacts and architectural data only for the interpretation of planter lifestyles had also become obsolete. For example, the uncritical use of such terms as ‘Kormantse’, also written in various forms (Cormantyne, Kramanti, etc.) to describe groups of enslaved people passing through the then Gold Coast port of that name in West Africa (Figure 3) continued to plague the archeological literature and discourse. But other gains have been made.

Explaining burial and mortuary practices among different African societies as a means of deriving models that would help reconstruct life experiences of the enslaved in the African Diaspora was beginning to be appreciated. The bio-anthropology laboratory at Howard University embarked on an ambitious examination of skeletal remains of the African Burial Ground in Manhattan, New York bringing hope of reconstruction of the identities and past experiences of the enslaved. Similarly, studies relating to settlements of Maroons and free slaves, houses, yards or compounds, diet, diseases, physical effects of slave labor in Jamaica, Bahamas, and other Caribbean areas as targets of archaeological research which followed the 1990s, continued to yield lots of good results. Regardless of all these developments and advances in approaches toward explaining slavery in Africa and its relations to the Atlantic slave trade, much remains to be done. Kwaku Senah, an African historian in Trinidad and Tobago, who has researched ‘Slavery’ from the African perspective, in a 2005 article notes that the main problem might be that the term ‘slavery’ has acquired an expanded meaning to serve a vast number of purposes and blames it partly on the languages in which the term is discussed. Or is it to be concluded that ‘‘slavery cannot be identified through archaeological efforts alone’’?

See also: Africa, Historical Archaeology; Africa, West:

Villages, Cities, and States; Americas, Central: Historical Archaeology in Mexico; Americas, North: Historical Archaeology in the United States; Americas, South: Historical Archaeology.

World History

World History

![Stalingrad: The Most Vicious Battle of the War [History of the Second World War 38]](https://www.worldhistory.biz/uploads/posts/2015-05/1432581864_1425486471_part-38.jpeg)