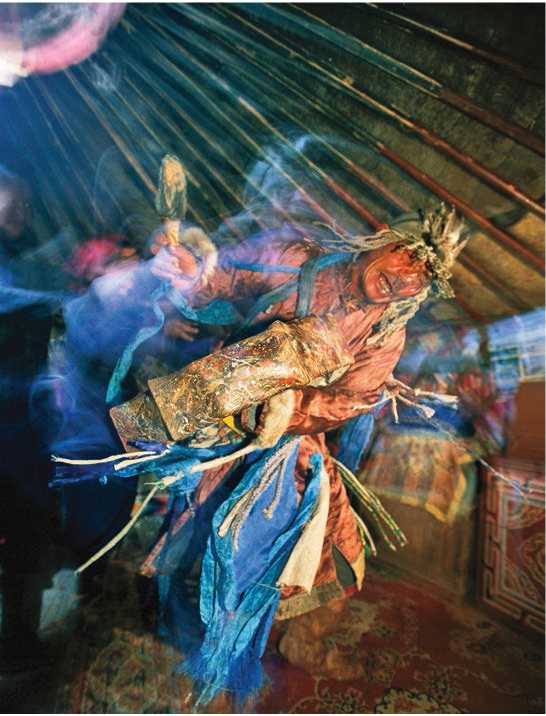

The Siberian hunter cultures view death as a process of transformation and passage in space and time and often linked to the idea of a journey. Death is not a finality, but a continuation of this world in another far-off land, the land of the spirits and ancestors. Death releases the soul from the body with potential destructive consequences for the living. Shamans have the special power to enact this hazardous journey. By mounting a horse in a trance or by taking on the body of an animal double, the shaman can accompany the souls of the dead to make certain that they do not return. Some tribes have more than one type of shaman; among some groups they are ranked by their power, or they will be differentiated as white or black depending on what spirits they use and where they travel to. Among the Siberian peoples there are often a range of shamans. There are shaman bone-setters, women shamans with midwife duties, shaman smiths who make and put power into metal objects and branding irons for the animals. There are also shaman assistants who warm the drums by the fire and prepare the ceremonies (Figures 4.15 and 4.16).

Figure 4.15: A shaman dances in a ger, or yurt, before migration, Mongoiia. Source: Gordon Wiltsie/National Geographic Stock

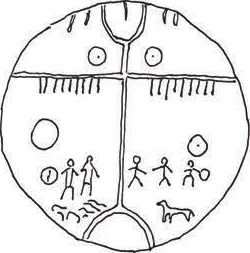

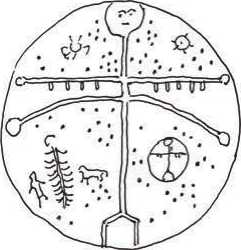

Figure 4.16: Shaman drums, Siberia. Source: Mark Jarzombek

A shaman’s work may vary from simple fortune telling to grand rituals lasting several days and nights. The shaman signals the beginning of his journey through dancing and beating on a one-sided, hand-held drum (tuur), usually 60 cm or more in diameter. Whereas we tend to see the drum as a musical instrument that provides the rhythmical backdrop to the song, the drum for the shaman is much more. Among some North Asian people, such as the Bon in Tibet, the drum is considered a type of vehicle that conveys the shaman through the air. It often has an image on it that serves as a type of map of the journey. In the upper part of the drum one might find suns or moons to indicate the heavens while the lower parts reaffirm the earth and its animals. Trees sometimes connect the two parts with antler-like branches or birds. Sami and Tartar drums tend to be more complex. The drums among the Northwest Indians of Canada might have birds painted on them. For the Northwest Coast people, the drum can represent the mythic cedar tree that is the cosmic axis.16

The shamanistic world presumes that the universe was produced as a system of layers ranged around a central pole, or World Tree. In poetic formations, that arrangement might be articulated in terms of the flow of rivers from south to north or from above to below or in terms of the cardinal directions, each of which is associated with forces of good or evil, life or death. The central element in this is the Blue Mighty Eternal Heaven—“Blue Sky” (known variously as Koke Tengri, Erketu Tengri, and Mongke Tengri). For the Mongolians, there are a total of 99 Tengris or sky-spirits in the lower and upper world, in which Koke Mongke Tengri (Eternal Blue Heaven) is the supreme. He is the creator of the visible and invisible world and envisioned as a white goose that flies over an endless expanse of water, which represents time. Another force is Koke Mongke Tengri who has a special relation with fire.

When a shaman dies, he or she is placed on wooden structures on the ground, or on raised platforms. The drum and headdress are placed with the body or hung on a nearby tree. The shaman may be more powerful than the chief and family heads. Shamanistic cults thus reflect a society that has accepted the location of unusual power within the hands of a single individual. Their position is dependent on their perceived skill and they are forced to defend their territory against other shamans, figuratively, if not literally.17

In 1931, a Russian ethnographer, Andrei Aleksandrovich Popov, was allowed to witness a shamanistic ritual organized by the Nganasans, who live on the Taymyr Peninsula in northern Siberia. A special tent was pitched for the rite. New tent poles were made, seven ones for each day of the rite. Three reindeer were sacrificed; their heads, legs, and hides were hung round the top of the tent. Tent covers were smeared with the blood. On the first day, the shaman, whose name was Dyukhade, had to go from his tent to the clean tent blindfolded. He began to shamanize in his own tent, singing the incantation addressed to the lord of the hearth. Then he was blindfolded and guided out of the tent where he was turned round several times. Despite this and the other attempts to impede him, he managed to arrive at the new tent. The tie was removed from shaman’s eyes. The first day of the rite was the stepping to the clean ground. On that day, the shaman did not ascend to the sky, but traveled only in the middle world. The day ended with a wordless song and a dance, with the participants all standing in a circle, holding hands and stamping. While dancing, the women imitated sounds of she-reindeer in heat. On the next day Dyukhade ascended to the second level of the heaven where a deity named Luonkari Barba was living. From it, Dyukhade asked for good fortune for everybody and for painless childbirth for all women. The deity bade him to show his capability. This was done by the spectators concealing the drum and Dyukhade having to find it, which he did. On the third day, Dyukhade ascended to a deity and asked for a year without diseases. The shaman had to perform another test. Similar encounters, requests, and tests took place over the next days until, on the seventh day, Dyukhade reached the highest level of the sky.

For this stage a long pole was erected in the middle of the tent. The shaman climbed up and poked his head out of the smoke vent. The pole symbolized the world-tree rising in the center of the highest sky level. On the top of the tree, the shaman encountered a deity and asked about the prospect for the future. The deity said, “Look round. If a bad year is coming, you can’t see the horizon in thick mist. But if a good year is coming, the horizon is perfectly visible and shines in the sunlight.” Dyukhade climbed down and said that he had seen the shining horizon. Dyukhade then began to swim across the Sea of the Dead. For this a pole was held horizontally by two assistants draped with the hide of a bear. The shaman, leaning against the pole with his arms in front of it, could then move his arms like he was swimming, and imitating sounds of the bear. All present in the tent stood in silence. They knew that with the shaman were the souls of the spectators themselves. They also knew that the souls of the people doomed to die during the next year would not be able to complete the swim to the shore with the shaman. After swimming for an hour, Dyukhade arrived at the shore and said that three souls had left him, and all expressed their sorrow. He then said, “Bad things I had not seen during my successful journey. You have now to strip off the covers of this tent.”18

World History

World History

![United States Army in WWII - Europe - The Ardennes Battle of the Bulge [Illustrated Edition]](https://www.worldhistory.biz/uploads/posts/2015-05/1432563079_1428528748_0034497d_medium.jpeg)