The Olmec were the first in Mesoamerica to institutionalize kingship with elites closing rank at the top of a hierarchical social order. Olmec material culture, including ceremonial offerings of precious imported materials, large-scale urban architecture, and monumental sculpture, provides a road map to that fundamental social process, demonstrating the stages by which it evolved.

A sacred landscape formed the platform upon which early kings founded their authority. The juxtaposition of an area of high ground with a water source characterized this landscape, which the Aztecs were later to call Water Mountain. It represented the place of creation, the source of life, or the navel of the world, the moral locus of royal power.

In the Gulf Coast region, worship at hills associated with springs have been traced back to the early third millennium at El Manati, according to Ortiz Caballos and del Carmen Rodriguez, coincident with the spread of agricultural communities and the evolution of crops such as maize. By the Early Formative period (1600-1200 BC) offerings of highly polished celts of exotic greenstone, some oriented to the cardinal directions, had been deposited together with rubber balls in the spring, which symbolized the point of entry into other worlds.

Emergent kings co-opted this sacred template at San Lorenzo (San Lorenzo Phase, 1150-900 BC), commandeering what was then a high island plateau strategically located in the middle of a Coatzacoalcos River tributary according to data produced by Michael Coe, Richard Diehl, and Ann Cyphers. The heart of the ritual center was a royal processional way aligned along the north-south axis of the plateau. Lining this processional way were at least 10 colossal stone heads representing portraits of past and present rulers. Sarcophagus-shaped thrones linked living kings directly with their ancestors, who are visible from cave-like openings in the stone.

The founding of Middle Formative centers marks a departure from the glorification of individual rulers and their royal bloodlines and the new objective of creating a heavenly place notes John Clark. As kings consolidated political power in the Middle Formative period (900-400 BC), they used the force of mimesis or mimicry to capture the ritual power of a sacred landscape. These Late Phase Olmec centers featured the ambitious construction of huge pyramids replicating the primordial sacred mountain. La Venta’s elites built atop a prominent salt dome that already dominated a now-extinct riverine environment. The pyramid is 30 m (98 ft) high and has a volume of about 100 000 sq. m (130 800 sq. yd). Carolyn Tate notes that the salt dome, now carrying its human-made mountain, was aligned to three real mountains arrayed in a triangular configuration to the south. The number three, expressed everywhere in the world (for example in majestic mountains, the celestial star cluster of Orion’s Belt, down to the humble stones of the domestic hearth) was itself a magical entity that infused the Olmec world-view.

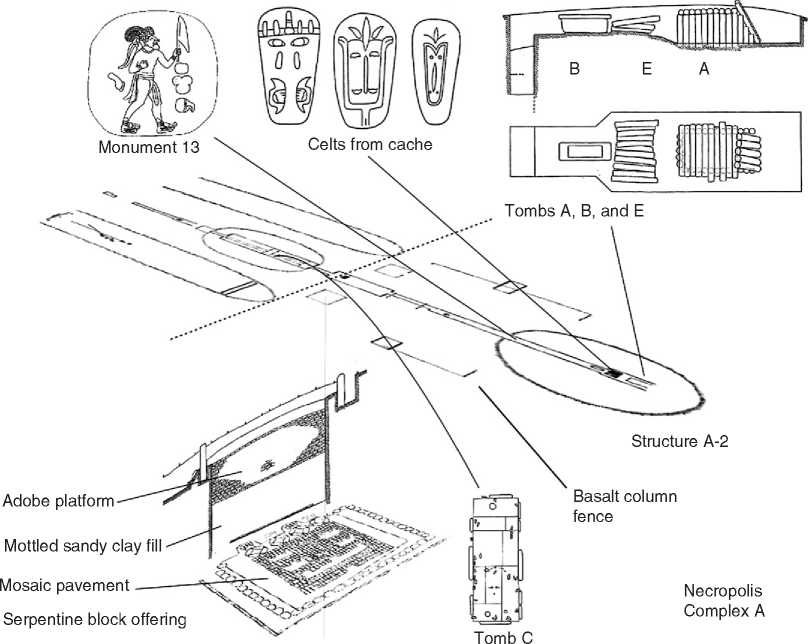

La Venta’s plan accessed all three levels of the Olmec universe. The pyramid touched the heavens. Serpentine mosaic pavements in the form of the quincunx, comprising the four directions and the center, as well as mirror-studded, cruciform caches of celts symbolizing the world tree, represented the surface of the earth. Huge pits filled with many layers of massive serpentine blocks represented seas deep within the earth according to Kent Reilly. La Venta Olmec innovated with stone stelae carved with images of deities and royal narrative scenes, which they inserted into the earthly plane. Sacred directionality and verticality encoded within the architecture of La Venta is reduplicated in incised and carved scenes throughout the Olmec world on larger sculpture and smaller ceremonial items such as greenstone celts.

Following the sacred water-mountain template, Olmec royal ceremonial plans included constructed water features to symbolize access to the earth’s fertility. Drains made of imported basalt must have had ritual as well as utilitarian uses, judging from associated sculpture. A San Lorenzo drain system went through a stone deity figure and led to a boulder carved into a basin in the shape of a huge duck. La Venta sculptors chose a more explicit image of fertility, fashioning a large basin in the form of a woman’s vulva.

Olmec ceremonial precincts were alive with color. Traces of plaster and paint on one of the San Lorenzo stone heads and in the mouth of a Teopantecuanitlan deity together with the presence of an uncarved stela excavated by Rebecca Gonztilez Lauck at La Venta indicate that artisans painted their stone monuments. San Lorenzo’s stone sculptures were arranged in ensembles and set in a huge plaza paved with red sand and yellow gravel. La Venta’s color scheme was stunning. Brown soil shot through with thousands of tiny bits of greenstone shimmered. Blue-green serpentine pavements were filled with clays and sands in olive green, blue, yellow, black, gray, pink, cinnamon, and purple hues, all imbued with symbolic meaning. Many of these offerings were buried soon after their construction and were invisible to ritual celebrants. Red paired with its contrasting color green was a dominant color combination. Red cinnabar covered jadeite offerings, and the whole site was covered in a cap of red clay in its final construction phase.

La Venta’s cosmic character derived from its celestial orientation. The hallmark Olmec site orientation to 8° west-of-north, its significance still obscure, was an ancient alignment that appeared early and persisted through the Olmec period. Olmec kings chose to found a ceremonial center on La Venta’s salt dome because its long axis is oriented to this sacred principle. The line that ran through the center of La Venta’s ceremonial precinct also matches this orientation and points directly to the central mountain of the cluster of three south of the center. The mountain is visible from the top of the pyramid. The central bars of each of La Venta’s mosaic pavements further parallels this alignment, and the four elements of the quincunxes are positioned at the intercardinal points where the sun rises and sets at the solstices.

Olmec ceremonial centers also had a strong orientation to the sun as the principal animating force of nature. Most importantly the elevated ground, the plateau at San Lorenzo and the salt dome at La Venta for example, would catch the first rays of the sun at sunrise. The Enclosure at the heart of Early Formative (1000-800 BC) Teopantecuanitlan featured Olmec-style monumental sculptures positioned so that the shadows cast by two of them passed through the center as the sun rose and set on the spring equinox. Loma del Zapote, located on the river below the San Lorenzo summit, featured sculptures of a kneeling humans facing the rising and setting sun. Backs of colossal carved heads at San Lorenzo itself are angled so that the king’s portraits faced upwards towards the sky. The present-day Mije term for the annual time periods and stations in the calendar, wi:npeht, means ‘eye rising’, perhaps explaining the orientation of the sculptures’ eyes.

A key new solar feature of great significance in the La Venta cosmic city (Complex D) was an E-Group configuration that was designed to track movements of the sun. A long platform and a radial structure were arranged opposite each other on the east and west sides of a plaza. Standing on the radial platform looking east, an observer could track the solstices at either end of the long structure and the equinoxes in the center. This architectural arrangement was widely copied at Soke sites along the Grijalva such as Chiapa de Corzo and at Maya sites in the Mirador Basin in northern Guatemala, according to John Clark. The E-Group is central to Classic Maya site planning, including to the site of Uaxactun, where the construction was first identified in the area archaeologists designated as Group E.

The Olmec kings posed as shamans dressed up as the sharp-eyed harpy eagles, allies of the storm and sun gods, a conceit that embodied the rulers’ insight into unseen forces of fecundity. The Olmec eagle-king painted sitting on a sarcophagus throne over the entrance to Oxtotitliin cave has huge eyes. Olmec elites may have enhanced their vision with psychotropic substances that produced ecstatic trance. The snuffing trays were likely greenstone ‘spoons’ with a central depression, scored or incised with a figure in flight, a common vision associated with ingestion of drugs, or topped with the crenellated eyebrow of the harpy eagle, another reference to supernatural vision. A San Lorenzo sculpture (Loma del Zapote Monument 11) shows male figure wearing such a ‘spoon’ suspended from his neck, ready for use.

The ballgame, so central to all Mesoamerican cultures, mimicked the sun’s cosmic cycle into and out of the Underworld. Olmec kings politicized the ball-game, adding human sacrifice, probably including war captives. A San Lorenzo carving depicts a jaguar mauling a probable ballplayer, and La Venta Stela 2 shows the king with a harpy eagle on his back attacking rival players with animal guises, one the whitetailed deer. These carvings support the idea suggested above that Olmec kings had adopted a theory of history expressed as the relationship of the victor to the vanquished (or predator/prey) known for the later Maya.

Blood needed to be drawn to ensure plenty of lifegiving water as well as sun. Children and infants were sacrificed during the Early Formative San Lorenzo phase at the El Manati spring and in the Middle Formative period in the pillared enclosure in the sacred compound at La Venta (Monument 7, Tomb A). Human remains were placed as offerings under monuments at San Lorenzo. La Venta’s Altar 4 shows an eagle-clad king holding a captive tied to a rope, and human bones occurred in feasting refuse at its client site San Andres. Kings performed autosacrifice to draw their own blood on behalf of the community as well, judging from real and jadeite effigy stingray spines deposited in caches in La Venta’s sacred precinct.

Pilgrimage to sacred hotspots was a core attribute of Olmec ritual life. At the height of San Lorenzo’s power, pilgrims traveled to El Manati springs to deposit sacred insignia of kingship such as wooden busts of male and female ancestors accompanied by precious jadeite jewelry and scepters, one with a shark’s tooth and a bird effigy at either end. A finely carved dark greenstone footprint effigy captures the essence of the journey. La Venta’s sacred spot was probably Rio Pesquero, the now-destroyed Veracruz site from which many gorgeous jadeite objects have come. The jadeite representations of the king from Rio Pesquero constitute a radical departure from the ancestral wooden busts or even the royal colossal heads of the Early Formative period. The Rio Pesquero engravings show the king as a divine being. One celt shows him as the embodiment of the world tree in the center of the quincunx holding the harpy eagle as a ceremonial bar.

Caves as well as springs were pilgrimage destinations to enhance the king’s divine status. Both natural features provided portals to other worlds and access to supernatural power and abundance as well as

Figure 5 Perspective view of Complex A, La Venta. After Drucker P (1952) La Venta, Tabasco: A Study of Olmec Ceramics and Art. Washington, DC: Bureau of American Ethnology, Smithsonian Institution, figures 10,14,19, 20, 22, 47, and 61.

Sacred, life-giving water. Murals in Juxtlahuaca and Oxtotitian caves in Guerrero preserve a record of Olmec painting traditions in the service of pilgrimage and ritual. A male striding figure is an iconic image in Formative Mesoamerican art; it occurs on early stelae with evidence for writing and the calendar at sites such as La Venta and Takalik Abaj, for example.

Middle Formative La Venta elites expanded the pilgrimage phenomenon, notes John Clark, installing royal Olmec images all along routes of travel as well as in remote locations. Along the ancient east-west intercoastal Pacific overland route with access by river to the Grijalva Basin, they carved the rock face at Pijijiapan with the image of a ruler flanked by two women in front of a cave entrance for instance. An example of a remote location is a sculpture of an eagle-helmeted ruler raising a four-segmented pole representing the world tree way at the top of San Martin Pajapan volcano in the Tuxtla Mountains. The image of the ruler duplicates that of one (Monument 44) found at the Stirling Acropolis, the royal palace at La Venta, establishing the mountain top as the king’s royal domain.

La Venta’s rulers understood that enactment of ceremonies on sacred stages kept the universe in play and kept them in power as divine kings (Figure 5). They likely designed La Venta’s sacred landscape to draw pilgrims to worship at the ceremonial center itself. Many participated in the animation of the world. The feet of pilgrims wore down a pavement at the center of La Venta’s ceremonial precinct. Music, drinking, and feasting were core elements of the action. La Venta Offering 3 contained miniature greenstone flutes along with beads in the shape of brewing pots. At San Andrtis, the La Venta client site 5 km to the northeast of the ceremonial center, feasting refuse contained large platters, drinking cups, and brewing jars.

La Venta’s Altar 7 (Figure 6) brings the oracular element from the caves to the ceremonial precinct. The central image is a huge duck-billed head projecting form a cave niche. To the duck’s right is a figure with bubble-like speech signs floating up to a sacred crossed band sign in a cartouche, a glyph-like element probably referring to portals to the gods. The condition of the altar and the associated imagery suggest night ceremonies. On the back of the altar, nocturnal kinkajou and owl figures join the diurnal harpy eagle. The surface of the altar was flaked off as though by strong heat, perhaps from torches staked

Figure 6 La Venta Altar 7. Most altars have a seated figure in the niche. This altar is unique because it has a masked colossal head with a duck’s beak mask in the niche. The use of such masks may have been linked to oracular speech in the context of ritual or dance. The bucal mask is compared to a pottery waterfowl beak from the nearby site, San Andres. Line component after Follensbee (2000: figure 105).

Nearby. Numerous grooves over the top of the altar suggest that the celebration involved the ritual sharpening of axes.

Olmec kings built their palaces within the ceremonial precincts. Ann Cyphers has excavated the impressive Red Palace at San Lorenzo, a substantial construction with its platform substructure, red floors, and basalt roof support, steps, and drain. The Stirling Acropolis is believed to have been the residence of La Venta’s paramount elites, but it remains unexcavated. The difference between the Red Palace and the Stirling Acropolis was that the Red Palace was a royal residence while the Stirling Acropolis, surrounded by the pyramid, E-Group, and the ballcourt, was a sacred one.

The colossal heads have captured archaeologists’ attention as the portraits of male Olmec rulers. The figures’ helmets have been thought to denote male ballplayers. La Venta figurines and sculpture demonstrate that women as well as men wore helmet-style headgear, however, and one must recognize that some of the colossal heads may represent royal women as well as men, suggests Billie Follensbee. There is a good possibility that the Olmec may have been bilateral, as were most pre-Columbian Mesoamerican societies. Several images portray a male ruler flanked by one or two women. The Pijijiapan relief, La Venta Stela 5, and La Venta Offering 4 are examples. The older women may represent the founding lineage. A tumpline carried by the woman on Stela 5 makes multilayered reference to her as both a nurturing bearer of food as well as the sacred relics that ‘planted’ La Venta as a sacred center.

This description of Olmec ritual precincts underlines the thematic commonalities among sites but demonstrates how Mesoamerica’s first kings advanced their status from royal to divine through their architectural and iconographic programs. Olmec elites played on basic human psychological instincts such as desire for communion with higher powers, altruism towards the community, and attraction to memorable events in a world that is essentially unmemorable. Anyone who has witnessed the pull of the present-day regional, now Christian pilgrimage to Tila, La Venta’s successor, can attest to the compelling, even coercive, power that such phenomena exert. Olmec kings used monumental constructions to advertise their power and monopolize labor and material resources, thereby preventing contenders from mounting any serious challenge to their authority.

Competition played a part in driving the evolution of royal power. The Early and especially the Middle Formative periods saw the growth of royal pilgrimage centers competing with San Lorenzo and La Venta. Teopantecuanitlan and Chalcatzingo offered access to alternative versions of sacred landscape, caves and the water-mountain topography. The evidence for captives and sacrificial victims in the context of feasting and the ball game suggests that physical coercion, warfare, and raiding were a factor in the political landscape. In this regard, the Olmec differed from their contemporaries in Oaxaca, where warfare played a significantly more overt role in state formation. The Oaxaca pattern of physical coercion was to become the dominant one in Mesoamerica culminating in the Aztec state.

Writing and the Calendar

Olmec elites developed writing in connection with their ritual practices, including the celebration of calendrical cycles. Mesoamerican people devoted enormous effort to developing and observing calendrical events, which focused on divination and prophecy. Olmec religious

Figure 7 San Andres roller stamp. Date indicative signs are compared to the Epi-Olmec Long Count initial series glyph from Stela C at Tres Zapotes. San Andres is a subsidiary elite site of the Olmec polity capital, La Venta, located some 5 km from the center. Redrawn after Pohl, etal. 2002.

Art is filled with iconographic messages. The evolution of writing involved the conversion of these images to language messages whereby the reader gets the writer’s precise message through representations of words, syllables, or consonants and vowels of a language. Writing was an important tool of early kings because it allowed them to capture and transmit the power of a message in a manner similar to their ability to capture the power of the sacred landscape by reproducing it (Figure 7).

The representation of walking provides a good example of the process. The Early Formative greenstone carving of a footprint from El Manati is essentially a proto-glyph. The image conveys the action, and the medium conveys its sacredness. The footprint sign then appears transformed into a written verb accompanying a striding figure on Middle Formative Monument 13 from La Venta.

Early iconographic and writing technology relied heavily on the roller stamp, which acted as a small printing press. The inked stamp would leave its mark when rolled across the human body, cloth, or bark paper. A Middle Formative greenstone mask from Rio Pesquero demonstrates how the living human body was a prime medium for the transmission of written messages, which were also considered to have a life of their own. The fact that most early writing was probably applied to skin and other perishable materials accounts for the scarcity of evidence for its existence.

Another early illustration of the evolution of writing occurs on an Early Formative roller stamp from Tlatilco in the Basin of Mexico dating to c. 1100 BC. The stamp shows a possible early Venus glyph aside a canonic Olmec-style head, all aligned with the quincunx and an early version of the flowershaped k’in glyph, a logograph denoting the word for ‘sun’ or ‘day’. Through iconographic image and written word, the roller stamp conveys the message of the sacred center of the world in connection with calendrical ritual. The stamp’s message summarizes the essence of Olmec religious culture.

Data from San Andreis are significant given the fragility of evidence for Formative period writing and the shaky context of most early finds. San Andres has yielded firmly dated evidence for writing on a roller stamp and on greenstone plaques that formed jewelry, perhaps an earspool. The artifacts occurred in the context of ritual feasting refuse that could be dated through both radiocarbon assay and pottery chronology to c. 650 BC. One greenstone plaque features the royal double merlon motif inside a cartouche signifying its status as a written word. These glyphs are logographs, signs that represent words or concepts.

The writing demonstrates that the Olmec had the 260-day divinatory almanac, which they were probably instrumental in developing and disseminating throughout Mesoamerica. This sacred calendar was comprised of a sequence of 13 numbers and 20 named days, whose permutations took 260 days to cycle through. The San Andreis roller stamp shows the glyph for the day sign three ajaw. In addition to the San Andres find in a feasting deposit, calendrical notations have also been reported from other special contexts, Oxtotitlan cave and Teopantecuanitliin, where one of the monoliths in the ceremonial Enclosure bears a flower and two bars, possibly a very early record of the 10-Flower day sign.

The Olmec used one or more logographs to advertise special messages and events in public contexts, and they also wrote longer texts, perhaps for more esoteric purposes. The Cascajal serpentine block, 26 cm by 21 cm, found in a quarry north of San Lorenzo and El Manati, contains strings of glyphs that in some cases demonstrate patterned structure. Many of the pictograph-like glyphs represent objects of ritual significance, such as the maize cob, flaming bundle of faggots, ‘spoon’, and throne. The fact that the block had a concave face suggests that its text was erased and re-inscribed, perhaps many times. The block probably dates to the end of the Early Formative period or the Middle Formative period.

Early Mesoamerican writing is characterized by variability in form. Many glyphs are idiosyncratic and evidently went extinct. Others such as the calendrically-oriented ajaw and k’in glyphs persisted and were adopted by other groups such as the Maya, who went on to develop Mesoamerican writing and the calendar most fully.

Local, Regional, and Extra-regional Exchange through Trade and Gifting

Olmec social, political, and religious structure demanded that energy be focused on importing substantial amounts of material into this stoneless, Gulf Coast floodplain habitat. Tons of basalt came to San Lorenzo, by river raft and overland, from the Tuxtla Mountains some 60 km to the northwest where remains of stone working have been found at Cerro Cintepec volcano. Stone masons carved high-quality, finegrained porphyritic basalt into royal sculptures while coarser stone went for utilitarian technologies such as maize-grinding tools known as manos and metates.

La Venta’s elites expanded on San Lorenzo’s stone sources. To the north, the island of Roca Partida in the Bay of Campeche provided naturally formed basalt columns for the sacred enclosures in Complex A. Most of the stone sources for monuments and offerings came from the south, however. Cerro Zempoaltepec provided schists, andesites, and dior-ites for sculptures.

Olmec elites were the first to designate greenstones (jadeite, serpentine, schist, gneiss, green quartz) as the standard of sacred preciousness symbolizing the life force in water and vegetation in Mesoamerica. The standard evolved over time according to Olaf Jaime’s study of over 1000 artifacts from El Manati (1600BC), El Macayal (1200-1000 BC), La Merced (1000-600BC), and La Venta (1000-400 BC). The Olmec used distinctive blue-green, black, and dark green jadeite and serpentine in the Early Formative period (1600-1200 BC). Sources for these stones occurred at a distance of up to 1000 km from the Gulf Coast region in eastern Guatemala’s Motagua Valley, especially the Tambor River area. Craft workers carved beads, celts, and representations of animals out of this extremely hard stone, transforming them into sacred objects of power through their labor.

In Middle Formative times (1000-400 BC), as Olmec elites at La Venta engaged in conspicuous consumption by constructing earthen mounds accompanied by massive serpentine offerings and caches, the dark greenstones gave way to serpentine and yellow-green jadeite. The Middle Formative sources were closer, that is, the Oaxaca-Puebla area (Cuicatlan, Sierra de Juarez, Tehuitzingo), perhaps influenced by rise of competing polities and balkanization of frontiers Jaime suggests. Quality of stone working declined significantly in many cases. Many of the greenstone artifacts were deposited in an unfinished state. William Rust uncovered evidence of serpentine working areas in Complex E, to the northeast of La Venta’s sacred Complex A.

Olmec elites at La Venta monopolized the most desirable yellow-green stone, leaving their client supporters to make do as best they could in the face of poor supply lines. Allison Perrett’s study of greenstone from the subsidiary site of San Andsis showed that the material was unexpectedly abundant but was inferior in color and texture, exhibiting a blue-green hue compared with La Venta. Evidence for serpentine debitage at San Andsis, though scarce, demonstrates that the material was worked locally, however.

Complex networks of long-distance trade and exchange define Formative period Gulf Coast urban societies. Obsidian and ceramics provide the best opportunity to gauge the extent of these connections because the material is plentiful, many sources are known, and scientists can trace the sources accurately. The data indicate that the Olmec drew on diverse resources from a broad geographical area and probably used social alliances to facilitate these supply lines.

Sharp-edged obsidian was in high demand in Mesoamerica, and trade in prismatic obsidian blades is closely associated with the emergence of elites. The obsidian data, which are based on systems of visual identification assisted by neutron activation analysis, demonstrate that the Olmec drew on a surprising number of sources though only a few dominated. Robert Cobean showed that the obsidian from the Early Formative San Lorenzo phase at San Lorenzo came predominantly from Guadalupe Victoria, Puebla, in Central Mexico, which at c. 300 km to the northeast was the closest source to the site. Other obsidian came from El Chayal, Guatemala, perhaps with participation of inhabitants of Kaminaljuyil. The probable route for the El Chayal obsidian was along the Soconusco coast and over the Isthmus of Tehuantepec.

The La Venta obsidian data indicate major changes in obsidian production and procurement in the Middle Formative period. As many as nine sources were represented at La Venta. Travis Doering reports that the dominant sources changed to Paredion in Central Mexico and to San Martin Jilotepeque in Guatemala, each more than 500 km from La Venta in opposite directions and not the closest available. Obsidian may have moved from Central Mexico south via the trade center of El Viejitn on the Veracruz coast. The Guatemalan obsidian indicates a change in route along the Motagua river to western Guatemala and then down the Grijalva river via the trading site of San Isidro to the Gulf Coast. Whereas obsidian blades had previously been manufactured near the quarry sites, now macrocores were traded and manufactured into blades in elite-controlled workshop areas such as at La Venta Complex D. The La Venta site had high quantities of the golden-green Pachuca obsidian from Central Mexico, confirming the fact that it was a highly prized commodity.

There is strong circumstantial evidence of elite involvement in obsidian manufacture and distribution at La Venta. A spent obsidian core incised with the sacred insignia of a harpy eagle was placed in a royal offering (Tomb C) in the most holy precinct of Complex A. Moreover, the obsidian from the subsidiary site of San Andres, 5 km northeast of the paramount center, came from the same sources as those at La Venta. The San Andriis obsidian showed no evidence of local manufacture, and it was a scarce commodity, occurring primarily in the ritual feasting context. Inhabitants of San Andreis completely utilized what obsidian they were able to obtain from La Venta using bipolar flaking techniques.

Recent neutron activation analysis by Jeffrey Blomster of carved white ware fine paste ceramics and source clays from San Lorenzo and six other regions in Mesoamerica indicates the presence of long-distance trade in ceramics extending from the Olmec region to the Highlands. In this study, fine paste Early Horizon ceramics were demonstrated to be both of local manufacture and imported from the San Lorenzo region. The implications of this study place Early Formative San Lorenzo in a paramount position vis vis the social interaction, gifting and trade systems that underpinned the formation of the Early Horizon beginnings of Mesoamerica.

There are clues to the social impact of this geographically extensive, labor-intensive economic activity, for example, in the formation of alliances along trade routes. The enactment of social relations typically involved gifting of pottery in Mesoamerica, and the neutron activation data tracing the movement of pots out of the Gulf Coast heartland are tangible testimony to alliance corridors. Middle Formative Grivalva sites with strong Olmec influence provide hints that these alliances might have involved marriage between royal Olmec women and local lords. For example, New World Archaeological Foundation excavations at Chiapa de Corzo uncovered the burial of a woman, possibly an imported royal female lineage founder, accompanied by La Venta-style pottery. Ephemeral pieces of evidence from sites such as this in the Grijalva drainage provide hints of complex social relationships generated by Olmec trade and exchange.

World History

World History