According to legend, the Isle of Avalon lies below and beyond Glastonbury Tor, now more commonly known as the Somerset Levels. According to legend, Avalon is the Celtic paradise, rich in fruits and crops, that needed no cultivation. Geoffrey of Monmouth writes that King Arthur was brought here ‘mortally wounded’ from his last battle at Camlann, dying on a barge accompanied by weeping fairies. Avalon is associated with this Celtic m>thological ‘otherworld’ in the Arthurian legends. Arthur made a raid on the ‘otherwmrld’ to capture a magic cauldron kept safe by nine sorceress-queens, who were able to transform themselves into animals. It was here that the Celtic God Gwyn-ap-nudd made his kingdom of Annfwn and later was to become the fair>' king. In a further legend, he met the sixth-centur>' wandering saint, Collen (who had given his name to Llangollen).

In prehistory' this area was certainly a watery' marshland - an Iron Age lake village at the foot of the Tor was probably in use until after the Roman occupation and was then abandoned due to a rise in water level.

St Ninian’s Cave

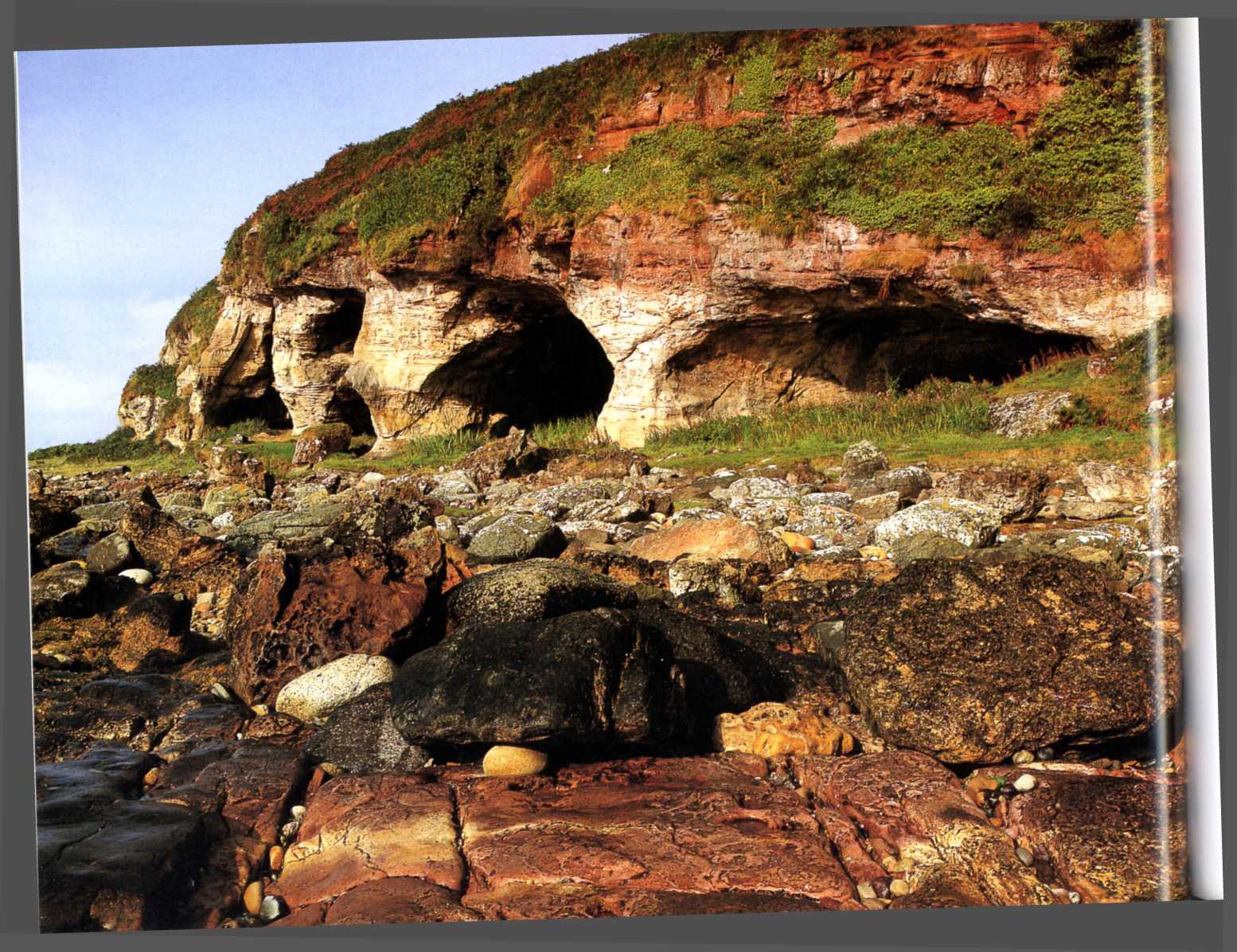

The King’s Cave Nr Blackwaterfoot, Isle of Arran, North Ayrshire

The King’s Cave is one of eleven caves created by the action of the sea on the soft red sandstone. They lie in the shadow of Drumadoon Iron Age hillfort, and can be reached by the coastal path around Drumadoon Point. The King’s Cave is 120 feet in length and thirt>- feet across, and it is shaped like the inverted wooden hull of a sailing boat.

The caves, according to legend, were used by early Celtic Christians. Incised on the w'alls of the King’s Cave, and difficult to see among the modem graffiti, are both Celtic and Pictish symbols: a broad sw ord cross, a horse, deer, and some concentric circles. There are examples of Ogham writing (a script in which the letters of the Roman alphabet are represented by short strokes).

A rough stone seat has been chipped out of the cave face.

The King’s Cave is where Robert the Bmce hid and campaigned from to attain the Scottish Crown. His fondness for this green and mountainous gem of an island was such that, in time, he was to form an honour guard from the men of Arran.

Isle of Whithorn, Dumfries and

St Ninian’s Cave is to be found about two miles south of this sleepy coastal town, and it is here that this Celtic holy man is reputed to have spent much time in meditation.

He was a contemporar>’ of St Patrick. However, unlike Patrick, comparatively little is known about him. Legend says he was the son of a king of Cumbria, w hile another account of his life claims that his mother w'as a Spanish princess. He travelled to Rome and on his return, when he was in his mid-thirties, he visited St Martin de Tours. Impressed with what he learned from Martin, and his monks’ simple way of life, he set up his own monastic settlement and school based on w hat he had seen in France. Soon his fame and teaching spread. He named his first church after Martin de Tours, Candida Casa, meaning ‘bright shining place’, which was later translated as ‘whitehom’!

Each 16 September, or on the nearest Sunday, hundreds of pilgrims follow' in the saint’s footsteps and walk from the Isle of Whithorn to a ser ice of dedication held in his cave.

The Manse Pictish Standing Stone Glamis, Angus

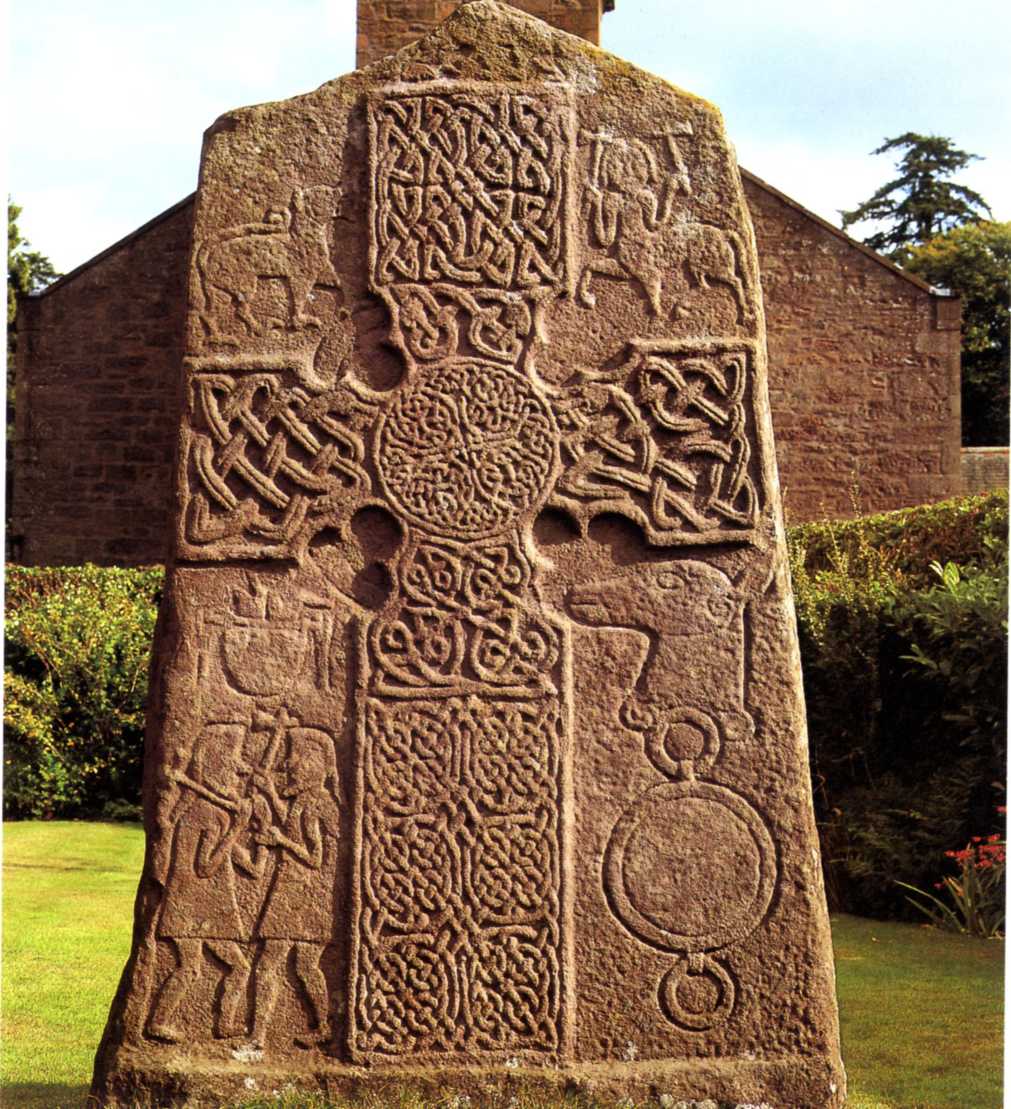

This beautiful half-Christian, half-pagan Pictish stone is found in the garden of the manse next to St Fergus’s Kirk.

After their conversion to Christianity by missionaries, the Piets still maintained their traditions of design and stone car ing. They did not produce freestanding crosses of the type being erected elsewhere, but from the seventh and eighth centur>’ started to incorporate both elements of their religion in their car ing. The St Fergus Manse Cross Slab is an excellent example of both the old and the new religions. The front of this large slab has been ‘dressed’, and a typical Celtic cross car ed in it surrounded by traditional Pictish motifs that we still do not fully understand. On the reverse of the slab, which is undressed, three symbols, typical of Pictish design, have been retained - a serpent, a fish and a mirror symbol. It has been suggested that these are probably much older than the Celtic cross on the front.

These stones, of which there are many, were probably used as devotional stones, and were positioned on trackways as a focus for prayer.

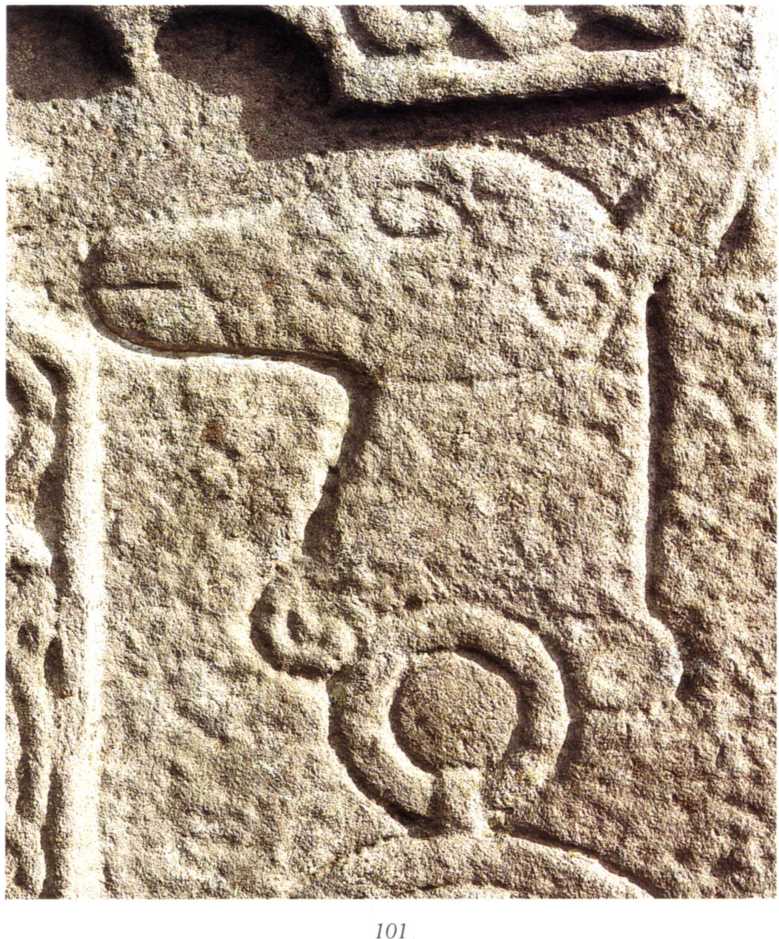

Pictish Symbols Glamis, Angus

The name Picti was first recorded in Latin in AD 297. At that time, and before, these people were known to have covered their bodies with tattoos and woad, they were the ‘painted people’. When Bede wrote seven centuries later about the Piets, no mention was made of this custom. It has been suggested that, with the passage of time, the symbols of rank adorning these people may well have been transferred to stone to commemorate an individual in death, indicating their rank, subtribe and name. There are about fift>- different and recognizable designs, which include mirrors, combs, hammers and swords. Others are abstract designs: Z-rods, V-rods and crescents. Animals such as fish, eagles and snakes also proliferate. The Glamis Manse Stone is one of many Pictish car ed symbol stones. Most still in situ are in the Moray, Aberdeenshire and Highland regions, however, few are as interestingly carved and in such good condition, and show the change from a pagan tradition to a Christian one. Today, though, the meanings of these carx ings can only be surmised.

World History

World History