Since the Neolithic, the global population of humans has grown steadily. The exact relationship between population growth and food production resembles the old chicken-and-egg question. Some assert that population growth creates pressure that results in innovations such as food production while others suggest that population growth is a consequence of food production. As already noted, domestication inevitably leads to higher yields, and higher yields make it possible to feed more people, albeit at the cost of more work.

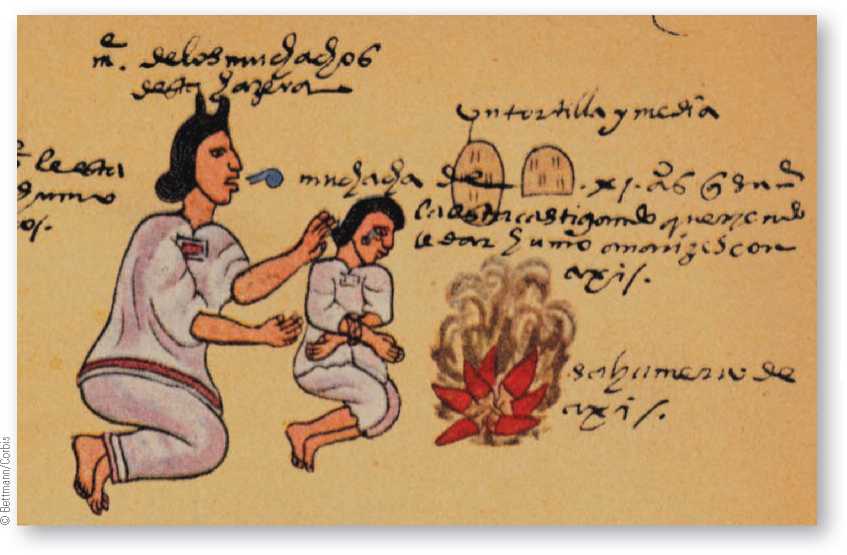

While increased dependence on farming is associated with increased fertility across human populations,192 the reasons behind this illustrate the complex interplay between human biology and culture in all human activity. Some researchers have suggested that the availability of soft foods for infants brought about by farming promoted population growth. In humans, frequent breastfeeding has a dampening effect on the mother’s ovulation, inhibiting pregnancy in a nursing mother who breastfeeds exclusively. Because breastfeeding frequency declines when soft foods are introduced, fertility tends to increase.

However, it would be overly simplistic to limit the explanation for changes in fertility to the introduction of soft foods. Many other pathways can also lead to fertility changes. For example, among farmers, numerous children are frequently seen as assets to help out with the many household chores. Further, it is now known that sedentary lifestyles and diets emphasizing a narrow range of resources characteristic of the Neolithic led to growing rates of infectious disease and higher mortality. High infant mortality may well have led to a cultural value placed on increased fertility. In other words, the relationship between farming and fertility is far from simple, as explored in this chapter’s Biocultural Connection.

Biocultural Connection

Breastfeeding, Fertility, and Beliefs

20 Mintz, S. (1996). A taste of history. In W. A. Haviland & R. J. Gordon (Eds.), Talking about people (2nd ed., pp. 81-82). Mountain View, CA: Mayfield.

21 Sellen, D. W., & Mace, R. (1997). Fertility and mode of subsistence: A phylogenetic analysis. Current Anthropology 38, 886.

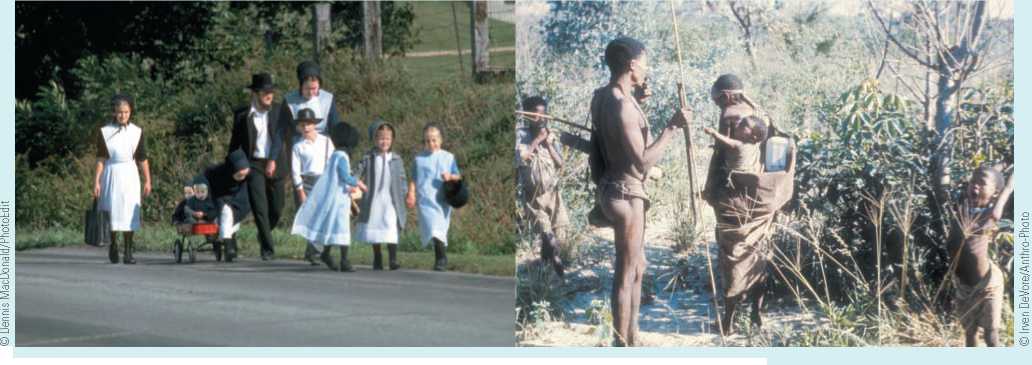

Cross-cultural studies indicate that farming populations tend to have higher rates of fertility than hunter-gatherers. These differences in fertility were calculated in terms of the average number of children born per woman and through the average number of years between pregnancies or birth spacing. Hunter-gatherer mothers have their children about four to five years apart while some contemporary farming populations not practicing any form of birth control have another baby every year and a half.

For many years this difference was interpreted as a consequence of nutritional stress among the hunter-gatherers. This theory was based in part on the observation that humans and many other mammals require a certain percentage of body fat in order to reproduce successfully. The theory was also grounded in the mistaken cultural belief that the hunter-gatherer lifestyle, supposedly inferior to that of “civilized” people, could not provide adequate nutrition for closer birth spacing.

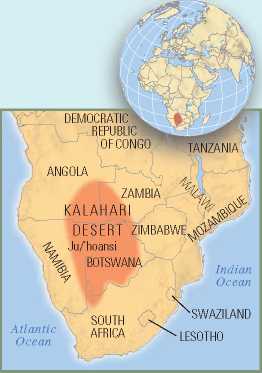

Detailed studies by anthropologists Melvin Konner and Carol Worthman, among the! Kung or Ju/'hoansi people (also, “Bushmen”) of the Kalahari Desert in southern Africa, disproved this theory, revealing instead a remarkable interplay between cultural and biological processes in human infant feeding.

Konner and Worthman combined detailed observations of Ju/'hoansi infant feeding practices with studies of hormonal levels in nursing Ju/'hoansi mothers. Ju/'hoansi mothers do not believe that babies should be fed on a schedule, as recommended by some North American child-care experts, nor do they believe that crying is “good” for babies. Instead, they respond rapidly to their infants and breastfeed them whenever the infant shows any signs of fussing during both the day and night. The resulting pattern is breastfeeding in short, very frequent bouts.

As Konner and Worthman document,® this pattern of breastfeeding stimulates the body to suppress ovulation, or the release of a new egg into the womb for fertilization. They documented that hormonal signals from nipple stimulation through breastfeeding controls the process of ovulation. Thus the average number of years between children among the Ju/'hoansi is not a consequence of nutritional stress. Instead, Ju/'hoansi infant feeding practices and beliefs directly affect the biology of fertility.

BIOCULTURAL QUESTION

From both evolutionary and child development perspectives, what might be the advantages of breastfeeding babies for the first few years of life? What cultural processes work against this in your culture?

® Konner, M., & Worthman, C. (1980). Nursing frequency, gonadal function, and birth spacing among! Kung hunter-gatherers. Science 207, 788-791.

The higher fertility of the Amish, a religious farming culture in North America, compared to that of the Ju/'hoansi hunter-gatherers from the Kalahari Desert, was originally attributed to differences in nutrition. It is now known to be related to differences in childrearing beliefs and practices.

World History

World History