In ancient fields, excavation and coring reveal the seedbed (plowzone or A horizon), which may be on the modern surface or buried. Agricultural soils are impacted by soil type, environment, crops, cultivation regime (e. g., intensive or extensive), tools, and cultural traditions. Geoarchaeological techniques are employed to determine the fertility and stability of palaeosols. Common bulk soil analyses include quantification of crop-limiting nutrients (e. g., organic matter, phosphorus, nitrogen), soil particle size, and magnetic susceptibility. Intact soil blocks are analyzed through soil micromorphology (thin section analysis) to reveal preservation conditions by identifying soil structure, the distribution of soil constituents, and bioturbation.

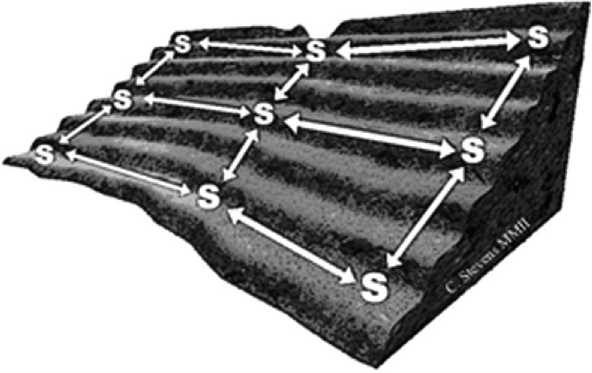

Geoarchaeological analyses of fields are best compared to uncultivated lands for accurate assessment of human impacts. Triplicate replication of soil conditions (i. e., collecting samples from three fields with similar physical settings) further controls for variations across agrarian landscapes (Figure 3). When preservation is outstanding, excavation may unearth anthropogenic features such as plow marks and furrows (cf. Figures 2, 4a, and 4b).

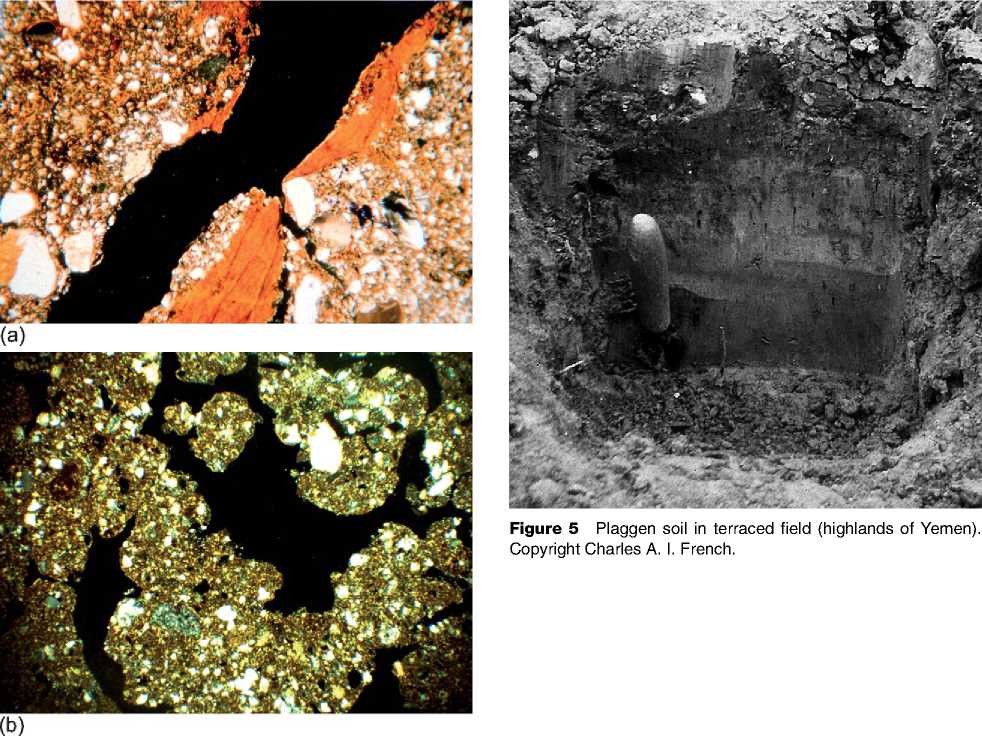

Differences in soil color, nutrient concentration, and soil particle size are used to identify land-use impacts. Long-term soil management is seen from the development of plaggen soils, dark nutrient-rich anthropogenic soils resulting from repeated applications of fertilizer-like dung (Figure 5). In arid regions, nutrients such as phosphorous may be retained for millennia. In contrast, overuse and erosion are revealed by reduced concentrations of silt, clay, and soil nutrients when field soils are compared to uncultivated controls.

Crops

Studies of cultigens often originate in settlements where macrobotanical remains indicate the consumption and use of cultivated plants (see Plant Domestication). In contrast, macrobotanical remains excavated from within fields are only reliable from intact palaeosols because of the potential for modern contamination, augmented by industrial tillage, bio-turbation, and organic decay. Pollen and phytoliths may be more stable in fields and can provide in situ confirmation of cultigens when recovered from secure contexts. Phytoliths are preserved under different conditions than pollen and may also reflect different crop species than pollen (see Phytolith Analysis; Pollen Analysis). Regional palaeoenvironmental reconstructions, contemporary agronomic studies, and surface vegetation provide additional insight into ancient cropping regimes. Increasingly, research into cultigens combines several methods with attention to sampling and preservation conditions.

Dating

Bioturbation, poor preservation of macrobotanicals, and modern disturbance also impact dating strategies. Dating may be further complicated by the sequential use of fields for different activities (see Dating Methods, Overview). Buried contexts under standing features, such as field walls or aqueducts, may provide secure contexts for recovering datable material. Optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) is increasingly used to date humic acids in soil (see Luminescence Dating). Surface and excavated artifact collections from gardens and fields provide additional chronological information.

Figure 3 Schematic of triplicate sampling pattern (S = sample collection point). Copyright Chris Stevens.

Figure4 Thinsectionsofsoilsfromancientfields. (a), Plowmarks in well-preserved buried palaeosoil, Welland Bank Quarry, south Lincolnshire, UK. Copyright Charles A. I. French. (b), Bioturbated palaeosoil from a pre-Columbian terrace (Paca, Peru).

World History

World History