A major factor determining expanding and receding ice sheets in high-latitude regions of the world, changing sea levels, mammal extinction, regional biotic restructuring, and the movement of Late Pleistocene fauna, flora, and people was climatic change. Although glacial ice sheets greatly affected the routes available to early migrants in the higher latitudes of North America and the southern Andes, they had little to no affect on the middle sections of North America, all of Central America, and most of South America. During the terminal Pleistocene between 13 000 and 11 000 years ago, sea levels were 70 or more meters lower than at present, and the Pacific and Atlantic shorelines were considerably farther out than their present position. As the continental ice sheets melted and retreated, the oceans rose and inundated most of the continental shelves. Most any early archeological

Sites along old shorelines have thus been destroyed or inundated by water. Widespread extinctions also accompanied these changes, particularly the loss of more than 30 genera of large mammals (for instance, ancient bison, horse, bear, mammoth, mastodont, and saber-tooth tiger). It is not known whether climatic change, human overkill (Figures 2 and 3), or both led to extinction. Major changes in vegetation communities also have taken place over the past 18 000-10 000 years. During the period from 13 000 to 10 000 years ago, when most American environments were likely inhabited by humans, temperatures were generally warmer in the summer and cooler in the winter, and rainfall was increasing. Patchy heterogeneous biotic zones were shifting to broadly homogenous mosaics with new and different mixtures of plant and animal species. In contrast to many interior regions, coastal areas displayed a combination of higher and more reliable and greater ecological

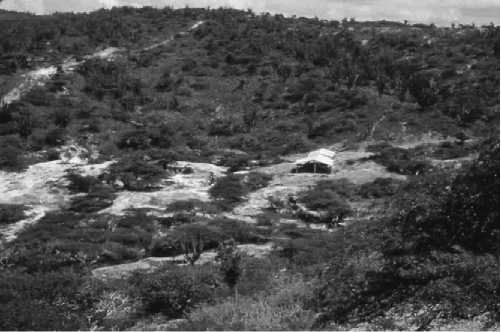

Figure 2 General view of the excavated springs at the Taima-Taima site in Venezuela where El Jobo projectile points were found with the bone remains of mastodont and other extinct animals. Courtesy of Alan Bryan and Ruth Gruhn.

Figure 3 Variety of El Jobo projectile points and other stone tools from the Taima-Taima site and other localities. Courtesy of Alan Bryan and Ruth Gruhn.

Diversity. These features may have been particularly desirable as cold and aridity reduced ecological productivity over much of the extreme northern and southern latitudes, but even in some of these areas human occupation may have been intermittently concentrated in short-lived warming episodes. In the high Andean mountains, for example, this is indicated by the pulsing of occupation at several caves and rockshelters and the abandonment of some areas.

Taken together, the palaeoecological and archaeological evidence is still a long way from accurately transforming palaeoclimatic data into clear statements about the productivity, availability, and reliability of resources for human use. On both a regional and local level, climatic shifts must have greatly influenced human land and resource use patterns, resulting in differential patterns of archaeological site location, abandonment and occupation, and artifact type and use. Yet, climatic factors, such as ice sheets, rainfall, and aridity, are only one among several (e. g., technology, social alliances, perceived alternatives) influencing human decisions to occupy, or abandon, parts of a landscape and how the archaeological record of each landscape is preserved for scientific study.

Certain regions of the Americas have received far better archaeological scrutiny than others. There are various reasons for this, often to do with logistics and conveniences and more commonly because of archaeological impact studies and changing scholarly research interests. For instance, densely populated parts of the United States have received greatest archaeological coverage, because they are where most modern development and impact studies occur and travel and access is easy. Some regions, such as the deserts of the American Southwest and the coastal plains of Peru and Chile, have a rich Late Pleistocene heritage and high archaeological visibility due to the absence of vegetation. On the other hand, there has been little archaeological field-work in the tropical forests of South America before the 1970s. In this region archaeologists have prospected more areas around rivers and lakes and in caves and rockshelters where accessibility and visibility are easier.

World History

World History