During the pre-Roman Celtic Iron Age, the fascination, respect and admiration for the animal world manifested itself time and time again in the incorporation of animal designs in art, particularly metalwork. Animals were represented in their own right, for example as figurines, but more often zoomorphic forms were selected to form the interwoven parts of what were essentially abstract designs. The whole period, from about 700 BC to the first century AD, was a dynamic one, as far as art was concerned. Indeed, it is possible to observe a developing and ever-changing tradition which made greater or lesser use of the animal form. In the earliest, Hallstatt, phase of the Iron Age, the decorative iconography reflects the customs and traditions of the time. This was an aristocratic, horse-riding society and thus horses (figures 3.9, 4.3) and horsemen were common subjects for art. Cattle figures, too (figure 2.1), reflect a herding society, where these animals were symbols and manifestations of wealth. The development of art in the early La Tene Iron Age saw a number of foreign influences at work - from Italy, Greece and further east, perhaps as far as Scythia and beyond. Animal designs are of particular importance, but those represented were not only the homely domestic or hunted creatures by which people were surrounded in their everyday lives. In addition, there are lions, griffins, sphinxes and other exotic or fantastic creatures in the iconography of European metalwork. During the fourth to third centuries BC, art veered more towards 'vegetal' or floreate designs, and animal motifs were, temporarily, of less significance. But in the later third to second centuries BC themes based on beasts reasserted themselves, as decoration on weapons, as mounts for vessels, as harness ornaments, as jewellery designs, and as figurines. By the very late Iron Age, when Roman influences became ever more apparent, things changed again: animals were once more prominent in iconography, with bulls, boars, deer and wolves as particularly favourite subjects. Horses were featured, above all, on coins. In Continental Europe, the vigour of Celtic art diminished in the first century BC, and with it the predilection for

Figure 6.1 Bronze chariot-fitting decorated with long-necked birds, probably swans, late fourth century BC, Waldalgesheim, Germany. Height: 7.6cm.

Paul Jenkins.

Zoomorphic imagery. By contrast, in Britain and Ireland, Celtic society remained alive for much longer and, consequently, Insular art continued to develop and blossom into the first century AD and, in Ireland, for even longer.1

This chapter depends very much on its illustrations, and it is impossible to describe the role played by animals in Iron Age art without constant reference to them. What I intend to do is to introduce the different kinds of object which were decorated by Celtic artists with zoomorphic themes and designs. Two artistic features stand out very clearly: one is the merging of realism and abstraction, so that the animal form is often distorted and manipulated into a flowing design. This is sometimes so successful that it may be necessary to study an object very carefully in order to perceive the animal theme at all. This ambiguity in design can be seen perhaps at its finest in the first-century BC or AD crescentic plaque (figure 6.2) from Llyn

Figure 6.2 Crescentic bronze plaque with central roundel decorated with triskele, the arms terminating in birds' heads, first century BC, Llyn Cerrig Bach, Anglesey. By courtesy of the National Museum of Wales.

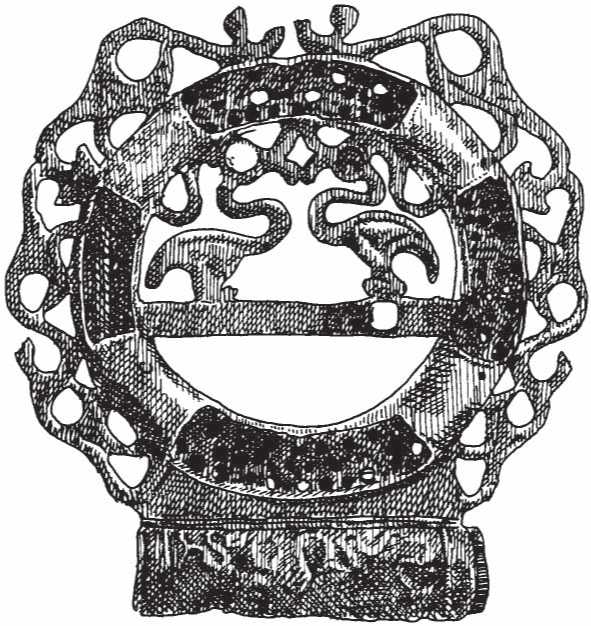

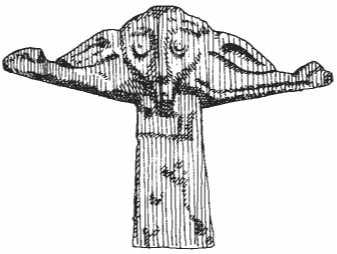

Cerrig Bach on Anglesey, where each element in a whirling triskele motif is a bird's head with a beak and large circular eye. There is an Irish horse-bit which is decorated with the heads of birds and humans:2 the central ring of the bit has ducks' heads at each side, but if the object is turned upside-down, these become, instead, a human face. So there is a sense in which the art may represent different things to different people and the way an observer 'reads' the art will reflect the message conveyed. The second feature of this 'animalizing' art is the manner in which human and animal forms may become mixed. Thus one often finds a human face or head but with the ears of an animal: a fifth to fourth century BC bronze sword-hilt from Herzogenburg, Austria, is ornamented with a human face with large, hare-like ears (figure 6.3). Bronze harness-mounts of the same date from Horovicky in Czechoslovakia are decorated with human heads bearing horns.3 So the Celtic artist was taking zoomorphic subjects but adapting them and subordinating them to his art: the art itself takes precedence and the incorporation of animal designs is a means

Figure 6.3 Bronze sword-hilt in the form of composite creature, with hare's ears and with arms terminating in birds' heads, fifth century BC, from a grave at Herzogenburg, Austria. Height of face: 1.1cm. Paul Jenkins.

To the end of producing pleasing art-forms. None the less, there is plenty of evidence that animals were studied and their forms and temperaments understood. Though an animal may be stylized, simplified or turned into something odd, the essential nature of a given beast was comprehended and somehow managed to manifest itself within the designs. A superb example of this is the horse-mask found at Melsonby (Yorks.) but almost certainly originally from the great stronghold of the Brigantes at Stanwick (figure 4.14). Here, the long, horse-shaped mask is marked with only a few simple lines to indicate what it is intended to represent, but the 'essence' of the animal is there.4

World History

World History