The evidence of literature and archaeology points to the high status accorded to horses in Celtic society. Many divinities were closely associated with them (chapter 8), and faunal remains from Iron Age sanctuaries such as Gournay-sur-Aronde (Oise) and Ribemont-sur-Ancre (Somme) point to reverential treatment of dead horses (chapter 5). At Gournay, seven horses which had died naturally were accorded special burial in the ditch.38 At the Ribemont shrine, the close association between man and horse is indicated by the presence of an ossuary, a kind of structure built from the long-bones of humans and horses.39 Rivers in Gaul contain ritual deposits of horse skulls, found in the same places as prestigious weapon-offerings.40 The esteem with which horses were regarded stems, above all, from their use by the aristocracy as war-horses or for display. At Camonica Valley, the rock art of the early Iron Age implies that ownership of horses was a luxury, reserved for leaders, warriors and hunters, and only these higher members of society are depicted riding. Camunians are first depicted on the rocks on horseback in the seventh century BC, fighting with swords, daggers and shields.41 It is suggested that horses may sometimes have been kept at Danebury as status symbols42 and, at the Iron Age site of Gussage, all the horses found were unbutchered, perhaps indicative of a taboo on the consumption of horsemeat,43 although horses were eaten elsewhere.

Other indications of the prestige enjoyed by horses include lavish harnesses and the fact that horses are not particularly useful in economic terms, being expensive to maintain and unsuitable for heavy traction.44

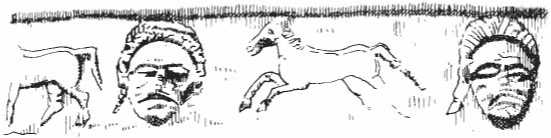

Classical writers endorse the notion that Celtic horses had high status, especially in association with warfare: a passage in Polybius's Histories describes a series of duels imposed by Hannibal on his Celtic prisoners-of-war on his arrival in Italy; the prize for the winning fighter included a cloak and a horse.45 At the Battle of Orange in 105 BC, the Teutonic tribe of the Cimbri made a vow to their gods, dedicating to them all their spoils, sacrificed enemies, weapons and horses on the battlefield.46 Caesar47 describes the equites or knights as the noble stratum of Celtic society; the literal translation of the term equites is horsemen, and the definition of a nobleman was someone who possessed a horse and arms. These knights were the cream of the Celtic warriors, who formed the cavalry contingent of the army.48 A number of classical writers, including Strabo,49 allude to the Celtic custom of headhunting in battle: 'when they are leaving the battlefield, they fasten to the necks of their horses the heads of their enemies.' Brunaux50 suggests that headhunting may have been the prerogative of horsemen. Certainly, this association between horses and severed heads is confirmed by iconographical evidence from the Lower Rhone Valley: a stone frieze from Nages (Tarn) is carved with alternating galloping horses and human heads (figure 4.6); and at nearby Entremont, a sculpture depicts a horseman with a severed human head slung from his harness.51

THE IMAGE OF THE HORSEMAN

In the La Tene Iron Age, depictions of horsemen appear on coins, jewellery, pottery, sculpture and metalwork. Mounted warriors and charioteers, both male and female (figure 4.13), are frequent motifs on Celtic coins;52 a silver coin from Scarisoara in Romania has a mounted soldier on the reverse.53 The southern Gaulish sanctuary of Roquepertuse was decorated with human skulls, perhaps those of battle-victims; here also were stone images of war-gods, and a stone frieze dating to the third or second century BC is carved with four horse heads.54 One panel of the Gundestrup Cauldron (figure 4.5) depicts various contingents of a Celtic army, including foot-

Figure 4.6 Stone frieze of alternating horses and severed heads from the pre-Roman oppidum at Nages, Provence, France.

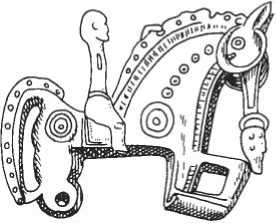

Figure 4.7 Iron Age bronze brooch in the form of a horseman, with a severed human head beneath the horse's chin, Numantia, Spain. Paul Jenkins.

Soldiers, horsemen and trumpeters with their boar-headed carnyxes.55 A pot made in the first century BC and discovered at Kelvedon in Essex is stamped with images of spiky-haired horsemen (perhaps with the lime-washed hair alluded to by classical writers on Celtic warriors), bearing hexagonal Celtic shields and curious crook-shaped objects.56 A brooch from Numantia in Spain (figure 4.7) depicts a naked, mounted warrior with his horse trampling a severed human head.57

In the Romano-Celtic period, Celtic warriors were still depicted, but mainly in the form of gods (chapter 8): thus the sky-god is shown on horseback (figure 8.7), riding down the monstrous forces of evil represented by a giant which is half-human, half-serpent.58 Among the tribes of eastern Britain, a Celtic version of Mars appears transformed from his Roman guise to that of a native horseman. He appears thus as Mars 'Corotiacus' (a native sobriquet) at Martlesham in Suffolk, and on a bronze figurine at Peterborough. Several little votive figures of horsemen were offered at the shrines of Brigstock in Northamptonshire. Stone warriors on horseback are represented, for instance at Margidunum (figure 4.8).59 A recent acquisition by the British Museum consists of a bronze figurine of a war-god mounted on a proud, high-stepping horse. It was discovered on the Nottinghamshire/Lincolnshire border near the Roman site of Brough and close to the Fosse Way. The rider wears a helmet, short tunic with leather thongs, and greaves. The horse is more carefully modelled than his rider, and his ornamental harness can clearly be seen. The high-stepping stance perhaps reflects the horse's participation in a procession or parade.60

World History

World History