Major issues include formation and maintenance of separations based on race, ethnicity, class, and gender. The archaeology of the African-American experience has expanded considerably. There is also research on historic sites occupied by Native Americans, often in conflict or other contact with European-Americans; Asians, especially Chinese immigrants; and Dutch, English, French, Spanish, and other European nationalities. Archaeology is increasingly common at historic house museums, typically expanding from an initial focus on the ‘great man’ history of the place to examine the rest of the household and settlement. Domestic sites of all time periods, locations, and economic class yield insights into the transformations of everyday life. Workers’ housing and boardinghouses provide the opportunity to investigate the effects of industrialization and the changing face of work and labor. Gender presents a special challenge that is being met in innovative ways.

An explosion of archaeology of African-Americans has often focused on plantation slavery but has expanded to consider the changing roles and situations of black Americans as slave and free, rural and urban. Plantation studies have undertaken to provide accounts of single plantations, experiment with Stanley South’s pattern-recognition technique, illuminate unique material expressions, and critique the archaeological treatment of slavery. Post-Civil War tenant plantations and Southern farms and the varying situations of free blacks provide opportunities for theorizing, analyzing, and describing strategies of power, expressions of all levels of ideology, and dynamic interactions among those attempting to dominate and those attempting to resist. The archaeology of slavery documents both covert slave resistance on plantations and overt resistance through sites of the Underground Railroad.

Dividing time within historical archaeology in the United States results in relatively short periods marked approximately by centuries. Some issues are specific to particular time periods, but most continue through several periods, ranging from the earliest explorations and effects of inter-cultural contact and ethnic diversity fueled by immigration, from the sixteenth century through the era of the Great Depression and until today to include modern material culture. Many types of sites are common to all the time periods, including domestic sites, farms, shipwrecks, gardens and other landscapes, and Native American settlements.

Exploration and Early Settlement

This time period of approximately the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries covers diverse issues, directly related to contact between native groups and both Europeans and Africans as well as adaptations that settlers from the old world made to new physical and social environments. Plantations and missions were established immediately when Europeans settled in the new world. Some notable site types are failed or abandoned colonies, early plantations, missions, fur trading posts, and early settlements along the East coast and in the Southwest.

The Grand Village of the Natchez on the Mississippi River was the main village of the Natchez society occupied before 1682 until 1730. Two platform mounds held the home of the leader known as the Great Sun in the main temple. French colonists described this village and some of the rituals they observed in this highly stratified society, providing accounts that help interpretations of Mississippian cultures in the Southeastern US.

In 1565 the Spanish founded St. Augustine, which served as capital of Spanish Florida for most of the period until it was ceded to England in 1763 under the Treaty of Paris. The second Spanish occupation lasted from 1784 until 1821, when La Florida became a US territory. Archaeology has been particularly important for interpreting women’s roles as culture-brokers in Native American and Spanish interaction. It has also revealed the adoption of aboriginal diet and food ways in the development of a Creolized culture. In addition, archaeologists have documented the decline of local indigenous people and the influx of other native groups from Georgia and South Carolina. These and many other investigations have made it clear that ceramic assemblages indicate far more than functional use; they may inform about symbolic interaction and group competition.

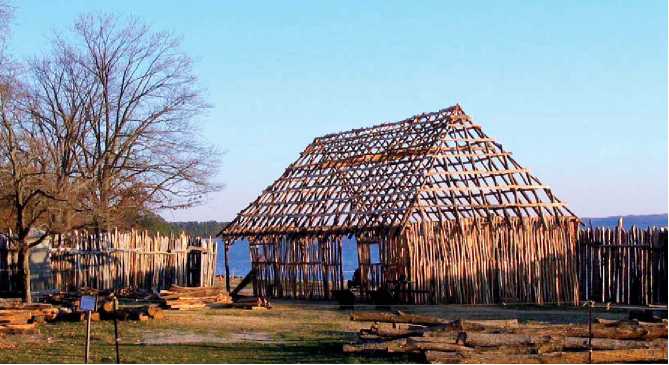

On Jamestown Island, in 1893 the APVA acquired more than 20 acres surrounding the old church tower and in 1934 the National Park Service acquired the rest of the island to establish Colonial National Historical Park. Projects of the 1930s and 1950s are well known (see above). Since 1994, APVA has discovered remains of the triangular 1607 James Fort, including the palisade wall lines, the east cannon projection, several cellars, a building, and several graves (Figure 1). Only a portion of the fort has been eroded away by the James River, although it was accepted for years that the fort had been lost. Analyses of hundreds of thousands of artifacts dating to the first half of the seventeenth century reveal details and patterns of the early colony, including

Figure 1 Reconstruction in progress of the barracks and palisade of James Fort, Jamestown, Virginia, in preparation for the 400th anniversary in 2007.

The discovery that the Virginia Company supplied the colony with up-to-date medical supplies and copper stock with which to fashion jewelry to trade with the Powhatan Indians.

The work on Martin’s Hundred by Ivor Noel Hume is a well-known excavation in the Chesapeake region. Within these 20 000 acres along the James River, the administrative center known as Wolstenholme Towne consisted of a palisade fort and several domestic buildings. Native Americans attacked settlements along the James River in 1622, devastating the European population. The burning of Wolstenholme Towne sealed a time capsule of early seventeenth-century plantation life that has been extensively excavated and has been interpreted for the public by Colonial Williamsburg.

Virginia’s first governor, Sir George Yardley, established Flowerdew Hundred in 1619 as one of many plantations along the James River. Archaeological surveys located dozens of sites related to European settlement and have yielded important insights into early relationships between European and African-Americans. Excavations also revealed a previously unknown small-scale iron smelting industry operating in the last quarter of the seventeenth century.

Excavations of St. Mary’s City revealed Pope’s Fort, dating to 1645 and related to the English Civil War and the Protestant rebellion against Lord Baltimore; investigations of the 1630s Jesuit Chapel uncovered burials of some of Maryland’s founders. Analysis of the town not only located several structures, including the 1635 governor’s residence and state house, a lawyer’s lodging, private homes, and public inns, but also indicates that Maryland’s first capital did not develop haphazardly but was a planned settlement incorporating concepts of Baroque urban design.

Eighteenth-Century Life

The character of European settlement in several regions changed from frontier to settled community. Plantations continued to be important but cities became increasingly so. This century saw the development of the Age of Reason, including new rules of behavior and hence new material culture, and the beginning of the industrial revolution within Anglo-American colonies. Plantations continued to be vital parts of the economic and social landscape until the end of the Civil War. Spain’s missions continued to be vital to their colonies in California and the Southeast. Some notable site types include missions, fur trading posts, cities, and battlefields and forts of the French and Indian War, and of the American Revolution.

The African Burial Ground in lower Manhattan in New York City was the burial site for that city’s enslaved population throughout the 1700s. The 1990s excavation, study, and reburial of over 400 individuals marks a watershed in historical archaeology in the United States in terms of public involvement. Analysis of the skeletal remains and burials reveal some direct connections to African cultural practices and symbolism as well as the physical hardships and effects of enslavement.

Fort Necessity in Western Pennsylvania was the 1754 scene of a pivotal conflict between England and France in the French and Indian War. Archaeology revealed that long-held assumptions about the fort’s precise location, size, and shape were wrong. Excavation identified the stockade and outer entrenchments and permitted an accurate reconstruction as a circular fort, which is managed by the National Park Service.

The Archaeology in Annapolis project excavated over 20 sites in Maryland’s capital, including formal gardens, colonial mansions, a print shop and artisans’ dwelling, and evidence of the baroque town plan. The project has explicitly focused on the development of the culture of capitalism and an innovative and influential public program.

Archaeology at Monticello, Thomas Jefferson’s plantation, and at Poplar Forest, Jefferson’s ‘other’ plantation, has provided insight into lives, work conditions, and accomplishments of white and black servants and slaves. As on other plantations, the analysis of food remains has been important for understanding ethnic and economic variability. Of particular importance is the analysis and understanding of a distinct culture that developed among African-Americans. In addition, the archaeology investigates Jefferson’s landscape design and the purposeful shaping of these places.

Nineteenth-Century Life

While manufacturing and iron production began in the colonies during the seventeenth century and crafts began to turn into industries in the eighteenth century, it is during the nineteenth century when full-blown industry and accompanying commerce appear. Industry changed the structure of wage labor, yet slave labor continued in agricultural, industrial, commercial, and domestic settings. The California gold rush stimulated migration West within the continent and also stimulated Chinese immigration. Notable site types include plantations, railroad sites, and many other types of sites associated with Manifest Destiny, Chinese terraced gardens, industrial sites including workers’ housing, battlefields, encampments, and other locations directly associated with the American Civil War and the Indian Wars.

Work at the early nineteenth-century Russian colony of Fort Ross in California goes beyond traditional studies of acculturation. Analysis in the context of mercantile colonialism reveals that Native American workers did not buy European goods, but acquired them as discarded items. They recycled materials such as nails and ceramic and glass sherds into objects that were useful in the Native American context and within a complex set of Native cultural strategies

Investigations at Harpers Ferry, West Virginia show peoples’ responses to changes in industry as the armory was transformed from a work place run by artisans to a factory of wage laborers run by the military (Figure 2). Workers were not silent about their disintegrating social and economic position. Reactions on the job to harsher work conditions and longer hours included work slowdowns, sabotage and, in one extreme case, murder. Families also made different consumer choices in this chaotic environment. During the early nineteenth century, when the lives and livelihoods of craftsmen appeared unthreatened and secure, the households of management and labor tended to follow the same fashions in choosing their Domestic goods. Later, in mid-century, the managers continued to adopt new styles. In contrast, laborers re-adopted old styles even while both cost and availability made the new and fashionable household goods accessible to the average armory worker.

At the Boott Mills industrial complex in Lowell, Massachusetts, excavations of the mill girls’ boardinghouses reveal that workers frequently disregarded corporate rules about behavior, particularly

Figure 2 Stratigraphic layers at the nineteenth-century Harpers Ferry Armory in West Virginia.

Concerning the consumption of alcohol. Other artifacts indicate that the mill workers sought to create distinct individual identities for themselves.

In 1865 the Steamboat Bertrand, bound from St. Louis for the newly discovered goldfields of Montana, sank in the Missouri River north of Omaha, Nebraska. In 1969 the vessel’s hull was completely excavated, yielding tools, clothing, food, and equipment which were in remarkably good condition because they had been preserved in an anaerobic, only slightly acidic, environment. Visitors to the DeSoto National Wildlife Refuge in Iowa may view the collection storage area that protects the cargo collection of 200000 artifacts. The objects bound for the mining towns may not be what one would expect to find on the raucous nineteenth-century American frontier. In addition to necessities, there was olive oil and mustard from France, bottled tamarinds and a variety of canned fruits, several varieties of alcoholic bitters, powdered canned lemonade, and brandied cherries. Such an inventory challenges assumptions about merchants on the frontier and provides an important resource for researchers of frontier life and consumer culture.

Like-a-Fishhook Village on the Missouri River in North Dakota was occupied c. 1845-85 by Hidasta, Mandan, and Arikara people who farmed and traded with Europeans. Excavations of this multicultural village revealed both traditional and modified housing built by members of these three distinct tribes and extensive evidence of the fur trade as well as the presence of Fort Berthold.

In 1983 an accidental grass fire exposed the surface of Little Bighorn Battlefield, providing the opportunity to examine the ground surface and to conduct archaeological investigations into this battle, which is one of the most famous of many conflicts over control of land and life in the American West. On June 25, 1876 the Seventh US Cavalry, led by Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer, engaged the Sioux and Cheyenne Indians in a battle that was part of the United States government’s military campaign against the tribes who refused to live within the boundaries of the Great Sioux Reservation and who were struggling to continue their traditional way of life. Because none of the 7th Cavalry combatants survived, there were no eyewitness accounts from whites. Historians had long held that the extensive Indian testimony was not accurate. Specific questions concerned where the participants of the battle took up positions and how they moved about the field. The archaeologists used geophysical techniques and excavation to translate artifact patterning into behavioral dynamics through the use of modern firearm identification procedures. The innovative archaeological methods created during these investigations changed the way that battlefield archaeology is done and raised expectations for results. Archaeological discoveries challenged historical details and versions of the battle and the findings support the idea that the Indian battle accounts are more accurate than those of the soldiers who buried the dead.

In another example of archaeology supporting ‘alternative’ history and challenging an accepted perspective is provided by an archaeological project commissioned by the Northern Cheyenne to document escape routes taken during the Outbreak from Fort Robinson, Nebraska, in 1879. Archaeological results successfully challenged official Army-based accounts of the escape by providing data that bolstered Cheyenne oral tradition. This is one of many examples where oral history and archaeology are mutually supportive in providing data and perspectives that contribute to a more accurate history in which biases and the politics of knowledge are acknowledged.

Excavations at the Millwood Plantation on the Savannah River in South Carolina provide insight into the transition between plantation slavery from the 1830s until the Civil War to post-war tenant farming lasting into the 1920s. Changes in settlement pattern reveal the search for greater freedom among formerly enslaved workers as quarters were replaced by clustered housing which was in turn replaced by more dispersed and independent houses.

Twentieth-Century Life

The economy of the United States continued to change after the upheavals of the Civil War and Reconstruction and with the impact of the Depression of the 1930s. Demography continued to change with immigration, anti-immigration laws, and internal migration. Notable site types include tenant farms, sites associated with mining, including mines themselves and mining camps; saw mills, logging camps, boom towns, work camps, and sites of conflicts between labor and capital.

Historical archaeology of mining spans several centuries and documents not only the extraction and refinement processes, but also the social life and culture of miners. The early twentieth-century remains of Reipetown in eastern Nevada reveal interesting anomalies of a mining town without evidence of internal class distinctions. No material culture evidence indicates consumer differences among documented households of ethnic Slavs, Greeks, Italians, Mexicans, and Japanese.

The Ludlow Massacre of striking coal miners and their families by the Colorado National Guard in April 1914 sparked an important turning point in labor relations in the United States. Archaeologists of the Ludlow Collective investigate this site not only to document the material evidence of the tent colony and its destruction but also to revive the memory of working class struggle.

World History

World History