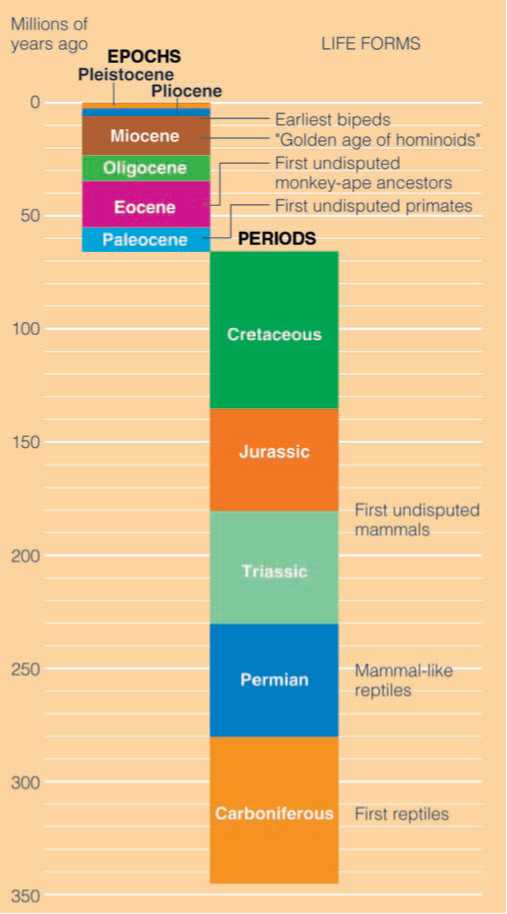

By 190 million years ago—the end of what geologists call the Triassic period—true mammals were on the scene. Mammals from the Triassic, Jurassic (135-190 mya), and Cretaceous (65-135 mya) periods are largely known from hundreds of fossils, especially teeth and jaw parts. Because

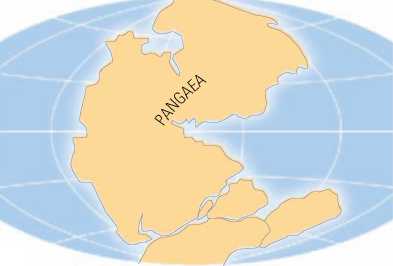

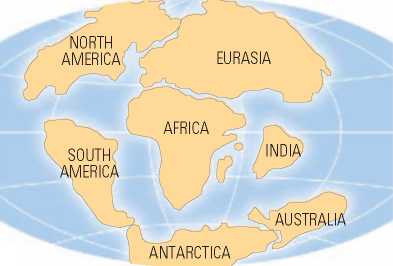

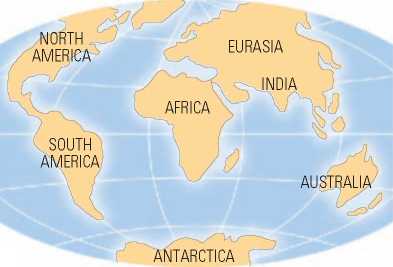

Continental drift According to the theory of plate tectonics, the movement of continents embedded in underlying plates on the earth’s surface in relation to one another over the history of life on earth.

250 million years ago

65 million years ago

Present

Figure 6.3 Continental drift is illustrated by the position of the continents during several geologic periods. At the time of the extinction of the dinosaurs 65 million years ago, the seas opened up by continental drift, creating isolating barriers between major landmasses. About 23 million years ago, at the start of the time period known as the Miocene epoch, African and Eurasian landmasses reconnected.

Teeth are the hardest, most durable structures, they often outlast other parts of an animal’s skeleton. Fortunately, investigators often are able to infer a good deal about the total animal on the basis of only a few teeth found lying in the earth.

For example, as described in Chapter 3, unlike the relatively homogeneous teeth of reptiles, mammals possess

Distinct tooth types, the structure of which varies by species. Knowledge of the way the teeth fit together indicates the arrangement of muscles needed to operate the jaws. Reconstruction of the jaw muscles, in turn, indicates how the skull must have been shaped to provide a place for these muscles to attach. The shape of the jaws and details of the teeth also suggest the type of food that these animals consumed. Thus a mere jawbone fragment with a few teeth contains a great deal of information about the animal from which it came.

An interesting observation about the evolution of the mammals is that the diverse forms with which we are familiar today, including the primates, are the products of an adaptive radiation: the rapid increase in number of related species following a change in their environment. This did not begin until after mammals had been present on the earth for over 100 million years. With the mass extinction of many reptiles at the end of the Cretaceous, however, a number of existing ecological niches, or functional positions in their habitats, became available to mammals. A species’ niche incorporates factors such as diet, activity, terrain, vegetation, predators, prey, and climate.

The story of mammalian evolution starts as early as 230 to 280 mya (Figure 6.4). From deposits of this period, which geologists call the Permian, we have the remains of reptiles with features pointing in a distinctly mammalian direction. These mammal-like reptiles were slimmer than most other reptiles and were flesh eaters. Graded fossils demonstrate trends toward a mammalian pattern such as a reduction in the number of bones, the shifting of limbs underneath the body, the development of a separation between the mouth and nasal cavity, differentiation of the teeth, and so forth.

Eventually these creatures became extinct, but not before some of them developed into true mammals by the Triassic period. During the Jurassic period that followed, dinosaurs and other large reptiles dominated the earth, and mammals remained tiny, inconspicuous creatures occupying a nocturnal niche.

By chance, mammals were preadapted—possessing the biological equipment to take advantage of the new opportunities available to them through the mass extinction of the dinosaurs and other reptiles 65 million years ago. As homeotherms, mammals possess the ability to maintain a constant body temperature, a trait that appears to have promoted the adaptive radiation of the mammals. Mammals can be active at a wide range of environmental temperatures, whereas reptiles, as isotherms that take their body temperature from the surrounding environment, become progressively sluggish as the surrounding temperature drops. Cold global temperatures 65 mya appear to be responsible for the mass extinction of dinosaurs and some other reptiles, while mammals, as homeotherms, were preadapted for this climate change.

Figure 6.4 This timeline highlights some major milestones in the course of mammalian primate evolution that ultimately led to humans and their ancestors. The Paleocene, Eocene, Oligocene, and Miocene epochs are subsets of the Tertiary period. The Quaternary period begins with the Pleistocene and continues today.

Adaptive radiation Rapid diversification of an evolving population as it adapts to a variety of available niches. preadapted Possessing characteristics that, by chance, are advantageous in future environmental conditions. homeotherm An animal that maintains a relatively constant body temperature despite environmental fluctuations. isotherm An animal whose body temperature rises or falls according to the temperature of the surrounding environment.

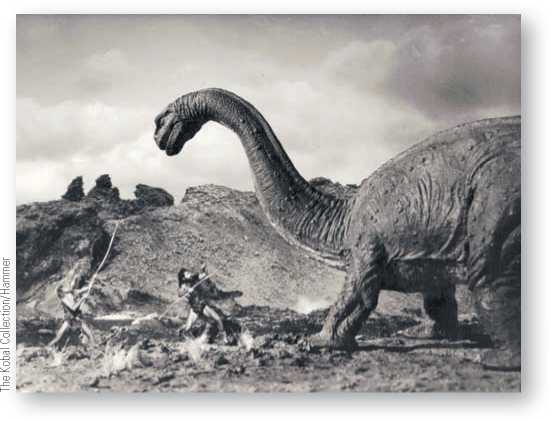

Though popular media depict the coexistence of humans and dinosaurs, in reality the extinction of the dinosaurs occurred 65 mya, while the first bipeds ancestral to humans appeared between 5 and 8 mya.

The appearance of the true seed plants (the angiosperms) provided not only highly nutritious fruit seeds and flowers but also a host of habitats for numerous edible insects and worms—just the sorts of food required by mammals with their higher metabolism. For species like mammals to continue to survive, a wide diversity of plants, insects, and even single-celled organisms needs to be maintained. In ecosystems these organisms are dependent upon one another.

However, the mammalian trait of maintaining constant body temperature requires a diet high in calories. Based on evidence from their teeth, scientists know that early mammals ate foods such as insects, worms, and eggs. As animals with nocturnal habits, mammals have well-developed senses of smell and hearing relative to reptiles. Although things cannot be seen as well in the dark as they can in the light, they can still be heard and smelled.

The mammalian pattern also differs from reptiles in terms of how they care for their young. Compared to reptiles, mammalian species are k-selected. This means that they produce relatively few offspring at a time, providing them with considerable parental care. A universal feature of how mammals care for their young is the production of food (milk) via the mammary glands. Reptiles are relatively r-selected, which means that they produce many young at a time and invest little effort caring for their young after they are born. Though among mammals some species are relatively more k - or r-selected, the high energy requirements of mammals, entailed by parental investment and the maintenance of a constant body temperature, demand more nutrition than required by reptiles. During their adaptive radiation, the fruits, nuts, and seeds of flowering plants that became more common in the late Cretaceous period provided mammals with high-quality nutrition.

K-selected Reproduction involving the production of relatively few offspring with high parental investment in each. r-selected Reproduction involving the production of large numbers of offspring with relatively low parental investment in each. arboreal hypothesis A theory for primate evolution that proposes that life in the trees was responsible for enhanced visual acuity and manual dexterity in primates.

World History

World History