Primates, like many animals, vocalize. They have a great range of calls that are often used together with movements of the face or body to convey a message. Observers have not yet established the meaning of all the sounds, but a good number have been distinguished, such as warning calls, threat calls, defense calls, and gathering calls. The behavioral reactions of other animals hearing the call have also been studied. Among bonobos, chimpanzees, and gorillas, most vocalizations communicate an emotional state rather than information. Much of the communication of these species takes place by using specific gestures and postures. Indeed, a number of these, such as kissing and embracing, are used universally among humans, as well as apes.

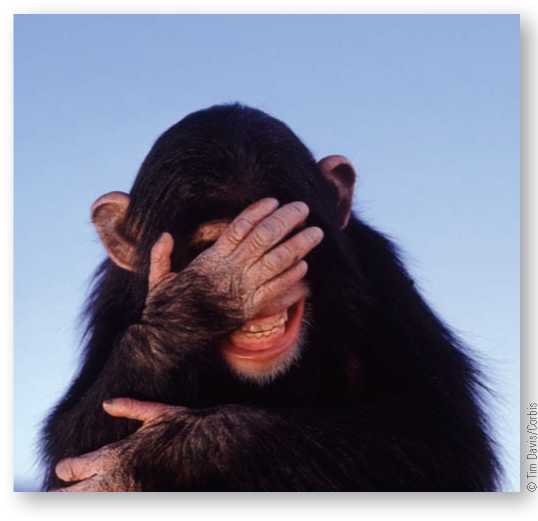

Primatologists have classified numerous chimpanzee vocalizations and visual communication signals. Facial expressions convey emotional states such as distress, fear, or excitement. Distinct vocalizations or calls have been associated with a variety of sensations. For example, chimps will smack their lips or clack their teeth to express

Many ape nonverbal communications are easily recognized by humans, as we share the same gestures.

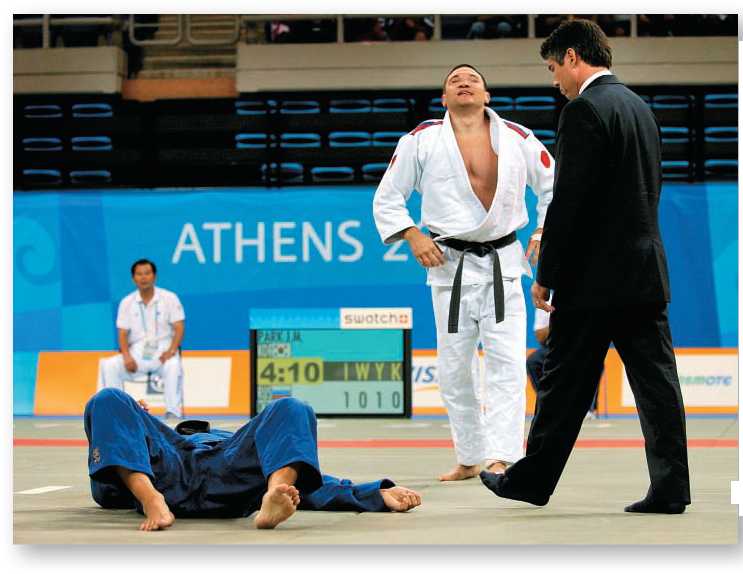

Athletes who have been blind since birth use the same body gestures to express victory and defeat as sighted athletes. Because they do this without ever having seen an “end zone” celebration, this indicates that these body gestures are hardwired into humans and presumably derive from our primate heritage.

¦i

Pleasure with sociable body contact. Calls called “pant-hoots,” which are used to announce the arrival of individuals or to inquire, can be differentiated into specific types. Together, these facilitate group protection, coordination of group efforts, and social interaction in general.

To what degree are various forms of communication universal and to what degree are they specific to a given group? On the group - specificity side, primatologists have recently documented within-species dialects of calls that appear as groups are isolated in their habitats. Social factors, genetic drift, and habitat acoustics could all contribute to the appearance of these distinct dialects.14

Smiles and embraces have long been understood to be universal among humans and our closest relatives. But recently some additional universals have been documented. Blind athletes use the same gestures to express submission or victory that sighted athletes use at the end of a match, though they have never seen such gestures themselves.15 This raises interesting questions about whether primate communications are biologically hardwired or learned.

Visual communication can also take place through objects. Bonobos do so with trail markers. When foraging, the community breaks up into smaller groups, rejoining again in the evening to nest together. To keep track of each party’s whereabouts, those in the lead, at the intersections of trails or where downed trees obscure the path, will deliberately stomp down the vegetation so as to indicate their direction or rip off large leaves and place them carefully for the same purpose. Thus they all know where to come together at the end of the day.50

Primatologists have also found that primates can communicate specific threats through their calls. Researchers have documented that vervet monkey alarm calls communicate on several levels of meaning to elicit specific responses from others in the group.51 The calls designated types of predators (birds of prey, big cats, snakes) and where the threat might arise. Further, they have documented how young vervets go about learning the appropriate use of the calls. If the young individual has uttered the correct call, it will be repeated by adults, and the appropriate escape behavior will follow (heading into the trees to get away from a cat or into brush to be safe from an eagle). But if an infant utters the cry for an eagle in response to a leaf falling from the sky or in response to a nonthreatening bird, no adult calls will follow.

From an evolutionary perspective, scientists have been puzzled about behaviors such as these vervet alarm calls. Biologists assume that the forces of natural selection work on behavioral traits just as they do on genetic traits. It seems reasonable that individuals in a group of vervet

14 de la Torre, S., & Snowden, C. T. (2009). Dialects in pygmy marmosets? Population variation in call structure. American Journal of Primatology 71 (4), 333-342.

15 Tracy, J. L., & Matsumoto, D. (2008). The spontaneous expression of pride and shame: Evidence for biologically innate nonverbal displays. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 105 (33), 11655-11660.

Monkeys capable of warning one another of the presence of predators would have a significant survival advantage over those without this capability. However, these warning situations are enigmatic to evolutionary biologists because they would expect the animals to act in their own self-interest, with survival of self paramount. By giving an alarm call, an individual calls attention to itself, thereby becoming an obvious target for the predator. How, then, could altruism, or concern for the welfare of others, evolve so that individuals place themselves at risk for the good of the group? One biologist’s solution substitutes money for reproductive fitness to illustrate how such cooperative behavior may have come about:

You are given a choice. Either you can receive $10 and keep it all or you can receive $10 million if you give $6 million to your next door neighbor. Which would you do? Guessing that most selfish people would be happy with a net gain of $4 million, I consider the second option to be a form of selfish behavior in which a neighbor gains an incidental benefit.

I have termed such selfish behavior benevolent.52

Natural selection of beneficial social traits was probably an important influence on human evolution, since in the primates some degree of cooperative social behavior became important for food-getting, defense, and mate attraction. Indeed, anthropologist Christopher Boehm argues, “If human nature were merely selfish, vigilant punishment of deviants would be expected, whereas the elaborate prosocial prescriptions that favor altruism would come as a surprise.”53

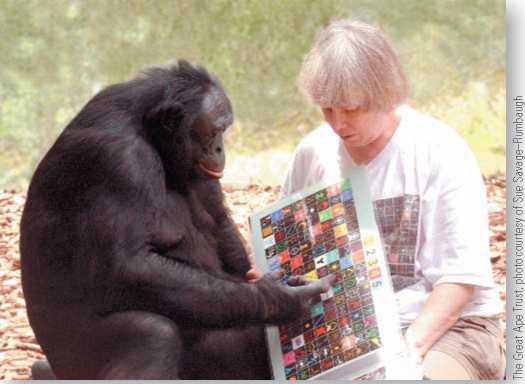

Evolution has shaped primates to be social creatures, and communication is thus integral to our order. Experiments with captive apes, carried out over several decades, reveal that their communicative abilities exceed what they make use of in the wild. In some of these experiments, bonobos and chimpanzees have been taught to communicate using symbols, as in the case of Kanzi, a bonobo who uses a visual keyboard. Other chimpanzees, gorillas, and orangutans have been taught American Sign Language.

Although this research is controversial, in part because it challenges notions of human uniqueness, it has become evident that apes are capable of understanding language quite well, even using rudimentary grammar. They are able to generate original utterances, ask questions, distinguish naming something from asking for it, develop original ways to tell lies, coordinate their actions, and spontaneously teach language to others. Even though

Kanzi, the 23-year-old bonobo at the Great Ape Trust of Iowa, communicates with primatologist Sue Savage-Rumbaugh by pointing to visual images called lexigrams. With hundreds of lexigrams, Kanzi can communicate thoughts and feelings he wishes to express. He also understands spoken language and can reply in a conversation with the lexigrams. Kanzi began to learn this form of communication when he was a youngster, tagging along while his mother had language lessons. Though he showed no interest in the lessons, later he spontaneously began to use lexigrams himself.

They cannot literally speak, it is now clear that all of the great ape species can develop language skills to the level of a 2- to 3-year-old human child.54 Interestingly, a Japanese research team led by primatologist Tetsuro Matsu-zawa recently demonstrated that chimps can outperform college students at a computer-based memory game. The researchers propose that human brains have lost some of the spatial skill required to master this game to allow for more sophisticated human language.21

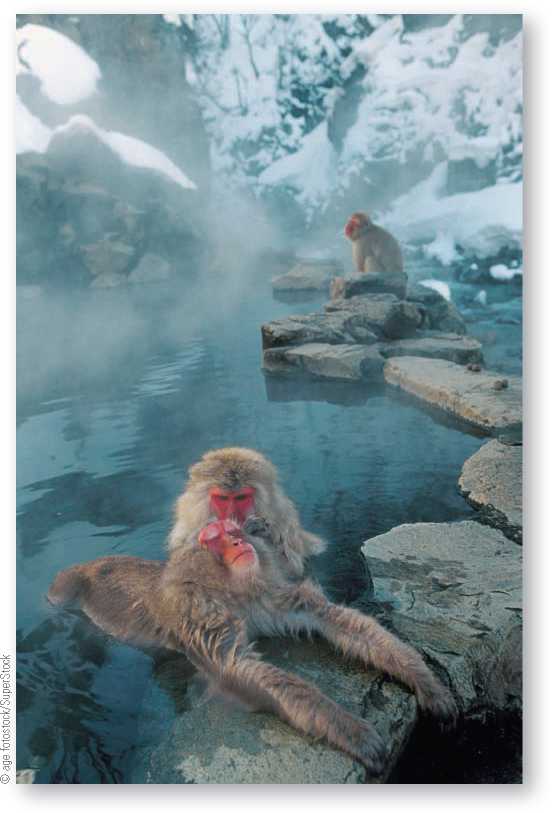

Observations of monkeys and apes have shown learning abilities remarkably similar to those of humans. Numerous examples of inventive behavior have been observed among monkeys, as well as among apes. The snow monkeys or macaques of the research colony on Koshima Island, Japan, are particularly famous for demonstrating that individuals can invent new behaviors that then get passed on to the group through imitation.

20 Lestel, D. (1998). How chimpanzees have domesticated humans. Anthropology Today 12 (3); Miles, H. L. W. (1993). Language and the orangutan: The “old person” of the forest. In P. Cavalieri & P. Singer (Eds.), The Great Ape Project (pp. 45-50). New York: St. Martin’s.

21 Inoue, S., Matsuzawa, T. (2007). “Working Memory of Numerals in Chimpanzees.” Current Biology, 17 (23), 1004-1005.

Altruism Concern for the welfare of others expressed as increased risk undertaken by individuals for the good of the group.

In the same way that young Imo got her troop to begin washing sweet potatoes in saltwater, at Kyoto University's Koshima Island Primatology Research Preserve another young female macaque recently taught other macaques to bathe in hot springs. In the Nagano Mountains of Japan, this macaque, named Mukbili, began bathing in the springs. Others followed her, and now this is an activity practiced by all members of the group.

In the 1950s and early 1960s, one particularly bright young female macaque named Imo (Japanese primatolo-gists always considered it appropriate to name individual animals) started several innovative behaviors in her troop. She figured out that grain could be separated from sand if it was placed in water. The sand sank and the grain floated clean, making it much easier to eat. She also began the practice of washing the sweet potatoes that primatologists provided—first in fresh water but later in the ocean, presumably because of the pleasant taste the saltwater added. In each case, these innovations were initially imitated by other young animals; Imo’s mother was the lone older macaque to embrace the innovations right away.

One newly discovered example is a technique of food manipulation on the part of captive chimpanzees in the zoo of Madrid, Spain. It began when a 5-year-old female rubbed apples against a sharp corner of a concrete wall in order to lick the mashed pieces and juice left on the wall. From this youngster, the practice of “smearing” spread to her peers, and within five years most group members were performing the operation frequently and consistently. The innovation has become standardized and durable, having transcended two generations in the group.55

Another dramatic example of learning is afforded by the way chimpanzees in West Africa crack open oil-palm nuts. For this they use tools: an anvil stone with a level surface on which to place the nut and a good-sized hammer stone to crack it. Not any stone will do; it must be of the right shape and weight, and the anvil may require leveling by placing smaller stones beneath one or more edges. Nor does random banging away do the job; the nut has to be hit at the right speed and the right trajectory, or else the nut simply flies off into the forest. Last but not least, the apes must avoid mashing their fingers, rather than the nut. According to fieldworkers, the expertise of the chimps far exceeds that of any human who tries cracking these hardest nuts in the world.

Youngsters learn this process by staying near to adults who are cracking nuts, where their mothers share some of the food. This teaches them about the edibility of the nuts but not how to get at what is edible. This they learn by observing and by “aping” (copying) the adults. At first they play with a nut or stone alone; later they begin to randomly combine objects. They soon learn, however, that placing nuts on anvils and hitting them with a hand or foot gets them nowhere.

Only after three years of futile effort do they begin to coordinate all of the multiple actions and objects, but even then it is only after a great deal of practice, by the age of 6 or 7 years, that they become proficient in this task. They do this for over a thousand days. Evidently, it is social motivation that accounts for their perseverance after at least three years of failure, with no reward to reinforce their effort. At first, they are motivated by a desire to act like the

Mother; only later does the desire to feed on the tasty nut-meat take over.56

A tool may be defined as an object used to facilitate some task or activity. The nut cracking just discussed is the most complex tool-use task observed by researchers in the wild, involving both hands, two tools, and exact coordination. It is not, however, the only case of tool use among apes in the wild. Chimpanzees, bonobos, and orangutans make and use tools.

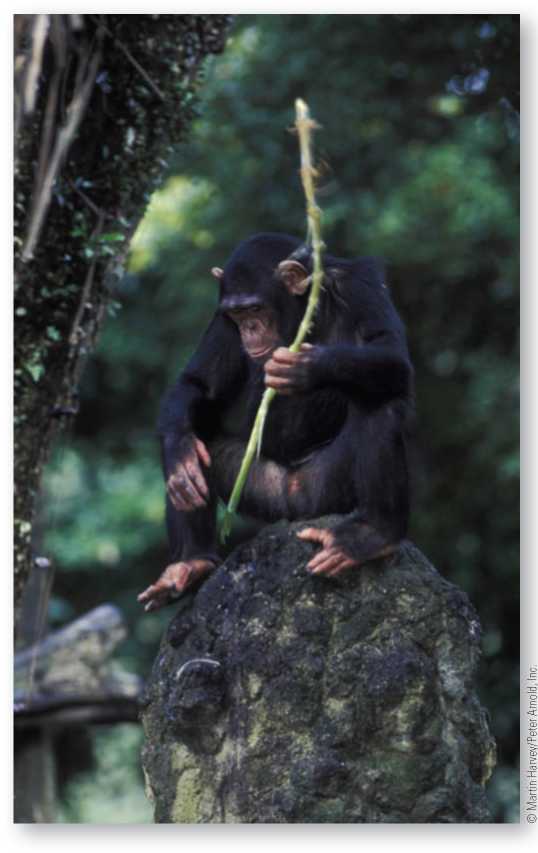

Here, a distinction must be made between simple tool use, as when one pounds something with a convenient stone when a hammer is not available, and tool making, which involves deliberate modification of some material for its intended use. Thus otters that use unmodified stones to crack open clams may be tool users, but they are not toolmakers. Not only do chimpanzees modify objects to make them suitable for particular purposes, but chimps also modify these objects into regular and set patterns. They pick up and even prepare objects for future use at some other location, and they can use objects as tools to solve new problems. Thus chimps have been observed using stalks of grass, twigs that they have stripped of leaves, and even sticks up to 3 feet long that they have smoothed down to “fish” for termites. They insert the modified stick into a termite nest, wait a few minutes, pull the stick out, and eat the insects clinging to it, all of which requires considerable dexterity. Chimpanzees are equally deliberate in their own nest building. They test the vines and branches to make sure they are usable. If they are not, the animal moves to another site.

Other examples of chimpanzee use of tools involve leaves, used as wipes or as sponges, to get water out of a hollow to drink. Large sticks may serve as clubs or as missiles (as may stones) in aggressive or defensive displays. Twigs are used as toothpicks to clean teeth as well as to extract loose baby teeth. They use these dental tools not just on themselves but on other individuals as well.57

In the wild, bonobos have not been observed making and using tools to the extent seen in chimpanzees. However, the use of large leaves as trail markers may be considered a form of tool use. That these animals do have further capabilities is exemplified by a captive bonobo who has figured out how to make tools of stone that are remarkably like the earliest such tools made by our own ancestors.58

Chimps use a variety of tools in the wild. Here a chimp is using a long stick stripped of its side branches to fish for termites. Chimps will select a stick when still quite far from a termite mound and modify its shape on the way to the snacking spot.

Chimpanzees also use plants for medicinal purposes, illustrating their selectivity with raw materials, a quality related to tool manufacture. Chimps that are ill by outward appearance have been observed to seek out specific plants of the genus Aspilia. They will eat the leaves singly without chewing them, letting the leaves soften in their mouths for a long time before swallowing. Primatologists have discovered that the leaves pass through the chimp’s digestive system whole and relatively intact, having scraped parasites off the intestine walls in the process.

Tool An object used to facilitate some task or activity. Although tool making involves intentional modification of the material of which it is made, tool use may involve objects either modified for some particular purpose or completely unmodified.

Although gorillas (like bonobos and chimps) build nests, they are the only one of the four great apes that have not been observed to make and use other tools in the wild. The reason for this is probably not that gorillas lack the intelligence or skill to do so; rather, their easy diet of leaves and nettles makes tools of no particular use.

Prior to the 1980s most primates were thought to be vegetarian while humans alone were considered meat-eating hunters. Among the vegetarians, folivores were thought to eat only leaves while frugivores feasted on fruits. Though some primates do have specialized adaptations—such as a complex stomach and shearing teeth to aid in the digestion of leaves or an extra-long small intestine to slow the passage of juicy fruits so they can be readily absorbed— primate field studies have revealed that the diets of monkeys and apes are extremely varied.

Many primates are omnivores who eat a broad range of foods. Goodall’s fieldwork among chimpanzees in their natural habitat at Gombe Stream demonstrates that these apes supplement their primary diet of fruits and other plant foods with insects and meat. Even more surprising, she found that in addition to killing small invertebrate animals for food, they also hunt and eat monkeys. Goodall observed chimpanzees grabbing adult red colobus monkeys and flailing them to death. Since her pioneering work, other primatologists have documented hunting behavior in baboons and capuchin monkeys, among others.

Chimpanzee females sometimes hunt, but males do so far more frequently. When on the hunt, they may spend hours watching, following, and chasing intended prey. Moreover, in contrast to the usual primate practice of each animal finding its own food, hunting frequently involves teamwork to trap and kill prey, particularly when hunting for baboons. Once a potential victim has been isolated from its troop, three or more adult chimps will carefully position themselves so as to block off escape routes while another pursues the prey. Following the kill, most who are present get a share of the meat, either by grabbing a piece as chance affords or by begging for it.

Whatever the nutritional value of meat, hunting is not done purely for dietary purposes, but for social and sexual reasons as well. Anthropologist Craig Stanford, who has been doing fieldwork among the chimpanzees of Gombe since the early 1990s, found that these sizable apes (100-pound males are common) frequently kill animals weighing up to 25 pounds and eat much more meat than previously believed. Their preferred prey is the red colobus monkey that shares their forested habitat.

Annually, chimpanzee hunting parties at Gombe kill about 20 percent of these monkeys, many of them babies, often shaking them out of the tops of 30-foot trees. They may capture and kill as many as seven victims in a raid. These hunts usually take place during the dry season when plant foods are less readily available and when females display genital swelling, which signals that they are ready to mate. On average, each chimp at Gombe eats about a quarter-pound of meat per day during the dry season. For female chimps, a supply of protein-rich food helps support the increased nutritional requirements of pregnancy and lactation.

Somewhat different chimpanzee hunting practices have been observed in West Africa.

At Tai National Park in the Ivory Coast, for instance, chimpanzees engage in highly coordinated team efforts to chase monkeys hiding in very tall trees in the dense tropical forest.

Individuals who have especially distinguished themselves in a successful hunt see their contributions rewarded with more meat.

Recent research shows that bonobos in Congo’s rainforest also supplement their diet with meat obtained by means of hunting. Although their behavior resembles that of chimpanzees, there are crucial differences. Among bonobos, hunting is primarily a female activity. Also, female hunters regularly share carcasses with other females, but less often with males. Even when the most dominant male throws a tantrum nearby, he may still be denied a share of meat.59 Female bonobos behave in much the same way when it comes to sharing other foods such as fruits.

While it had long been assumed that male chimpanzees were the primary hunters, primatologist Jill Pruetz and her colleagues researching in Fongoli, Senegal, documented habitual hunting by groups of young female and male chimpanzees using spears.60 61 The chimps took spears they had previously prepared and sharpened to a point and jabbed them repeatedly into the hollow parts of trees where small animals, including primates, might be hiding. The primatologists even observed the chimps extract bush babies from tree hollows with the spears. Because this behavior is practiced primarily by young chimpanzees, with one adolescent female the most frequently exhibiting the behavior, spear hunting seems to be a relatively recent innovation in the group. Just as the young female Japanese macaques mentioned above were the innovators in those groups, this young female chimp seems to be leading this behavior in Senegal. Further, the savannah conditions of the Fongoli Reserve make these observations particularly interesting in terms of human evolutionary studies, which have tended to suggest that males hunted while females gathered.

World History

World History

![Stalingrad: The Most Vicious Battle of the War [History of the Second World War 38]](https://www.worldhistory.biz/uploads/posts/2015-05/1432581864_1425486471_part-38.jpeg)