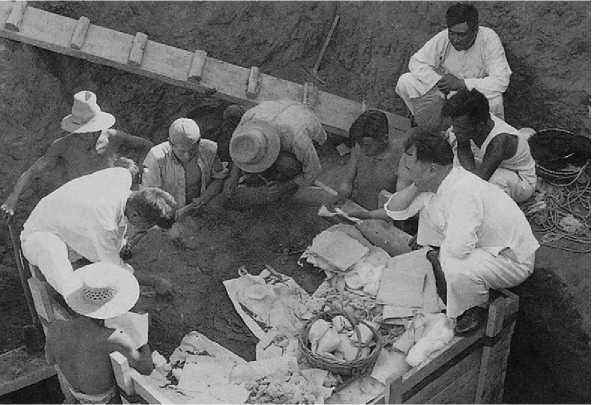

The first scientific excavations in China led by Chinese scholars occurred in 1928 at the late Shang (c. 1200-1045 BCE) site of Yinxu, Anyang, Henan Province. Intellectuals recognized early Chinese characters on inscribed ‘dragon bones’ sold in late nineteenth-century Beijing pharmacies and traced them to Anyang, spurring excavations by Li Ji, a Harvard-trained anthropologist, considered to be the father of Chinese archaeology (Figure 3). Excavations continued intermittently in the 1930s and 1940s because of war, but uncovered ‘oracle bones’ inscribed with the names of the last nine Shang kings. At a time when many intellectuals blamed blind adherence to tradition for China’s nineteenth - and early twentieth-century humiliations, the correspondence of the kings’ lists in ‘oracle bones’ to the names documented in the transmitted histories was considered a welcome indication of the truthfulness of tradition. This coincidence is largely responsible for archaeology’s historical approach throughout much of the twentieth century and its attempts to find places, people, and events named in the texts. At the end of the 1970s and 1980s, when economic reforms gave the provinces greater independence, more archaeological effort was directed outside the Central Plains, but the royal tombs, palaces, and workshops found at Yinxu still kept archaeological attention and resources focused on the Central Plains region for much of the twentieth century. It remains a major research center producing new and exciting finds.

Recently, the 5-year Xia-Shang-Zhou Chronology Project concluded. Funded by the Chinese government, the multidisciplinary project aimed to improve the accuracy of dates related to the first three historical dynasties in the Central Plains (Shang and Zhou are known from their own records; the Xia Dynasty is first recorded in the second century BCE Shiji). Although criticized as politically motivated, the

Figure 3 Li Ji at Yinxu excavations, Henan Province, China.

Project did much research, including archaeological work, and its results are now being published.

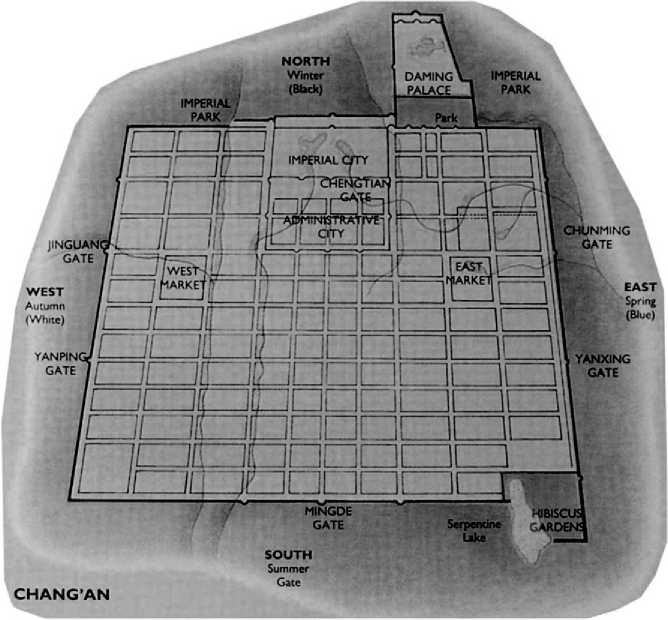

Dynastic capitals have also been a major focus of archaeological exploration. The Xi’an region of Shaanxi Province is the location of many capitals, including the Western Zhou period Feng and Hao centers (c. eleventh century BCE), mentioned in descriptive poems from the period; the Qin (221-206 BCE) city of Xianyang on the north bank of the Wei River; and the Han (202-220 BCE), Sui (581-618), and Tang (618-907) capitals on the south (Figure 4). Xi’an’s economic development has driven much of this archaeology over the past 30 years, and the general plans for the Han, Sui, and Tang capitals are now known. Walls, building foundations, residential quarters, roads, gates, and markets have been identified and excavated. Xianyang, the First Emperor of Qin’s (Qin Shi Huang’s) capital city, is eroded on its south by the river, but the purported Afang palace foundation has been uncovered along with other building remains. Capital cities for other dynasties have also been excavated including those of the Eastern Zhou period Qi and Lu states in Shandong; the Eastern Zhou and Eastern Han capital of Luoyang; the Northern Song capital at Kaifeng; and the Yuan (Mongol), Ming, and Qing capitals at Beijing. Several northern walled cities of non-Chinese dynasties have also been excavated including the Liao Dynasty (9071125) Middle Capital in Chifeng, Inner Mongolia, and the Mongol Yuan Dynasty’s (1272-1368) summer city at Shangdu (Xanadu), in Zhenglan Banner of Inner Mongolia.

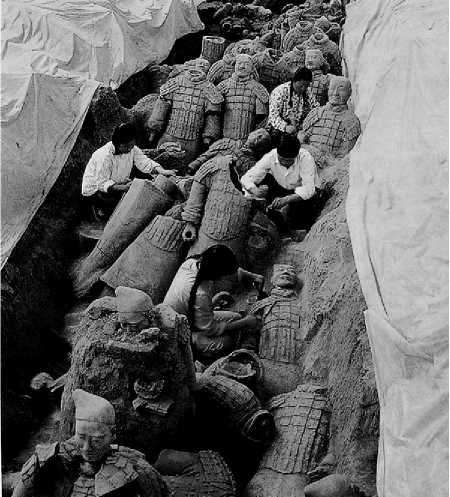

Mortuary archaeology is dominated by royal and elite tombs. China’s first large-scale tomb excavation was that of Ming Emperor Wanli, in the cluster of royal Ming tombs north of Beijing, undertaken in 1957 at the start of the Communist era and now an important tourist site. In Xi’an, the 1974 discovery of the pit containing the First Emperor of Qin’s ceramic army brought Chinese archaeology to the world stage, with figures and replicas traveling in goodwill exhibitions around the world (Figure 5). Ongoing excavations have uncovered two more pits with smaller armies of figures, and improved conservation and preservation techniques have retained some of the original pigments on their surfaces. The First Emperor’s tomb still awaits investigation, but Han and Tang period royal tombs in the Xi’an region have also been excavated. Legions of smaller ceramic figures also standing in rank were found in the Han Emperor Jing’s tomb of Yang Ling, and one Tang princess’s tomb contained well-preserved wall murals. Many tombs of nobility have also been excavated; including the 433 BCE mausoleum of Marquis Yi of

Figure 5 Excavations on figures guarding the tomb of the First Emperor of Qin, Xi’an, China.

Zeng in Hubei Province, who was buried with a full set of bronze bells and other court musical instruments, and the Han period Mawangdui tombs in Changsha, Hunan Province that contained numerous silk maps and documents and painted lacquer ware with cosmological representations.

World History

World History