Mal’ta is an open site 86 km south of Irkutsk at 52°50' N, 103°32' E. It is named after the village beneath which the Upper Paleolithic site was discovered. The typically unprosperous Siberian farming village sits on a flat, rolling plain, that today overlooks the Belaya River (Fig. 3.75). According to Mal’ta expert German Medvedev (personal communication, September 27, 2000) at the time of the late Pleistocene occupation of the Mal’ta site, the river did not exist; instead there were a series of lakes below the site and its companion site called Buret’ on the opposite shore of one lake (Lipnina et al. 1995). As they do today, villagers in the 1920s, digging in the ground to construct cold vegetable cellars or plant gardens, sometimes encountered bones of large animals. In the winter of 1927-1928 the Mal’ta village teacher-librarian sent word of these discoveries to the Irkutsk Historical Museum, which responded by having a young research fellow named M. M. Gerasimov check out the report. As a youth he developed interests in paleontology, archaeology, osteology, and related fields, so the Mal’ta discoveries fired up his eclectic interests in ancient Siberians. His findings would turn out to be among the most important in Siberian prehistory, as important as his developments in forensic anthropological reconstructions of human faces (Conant 2003, Gerasimov 1955).

The finds were confirmed and Gerasimov began in 1928 several years of archaeological testing (Gerasimov 1931, 1935, 1940, 1958) (Figs. 3.76-3.78). What his excavations eventually discovered included the now world famous Siberian human female bone figurines and bone carvings of water fowl, and other ornaments (Figs. 3.79-3.80), all in association with large amounts of mammoth bone refuse, bones of other animals, stone blade production, a large amount of stone tool manufacturing refuse, and outlines of dwellings and hearths, special analyses of which have been carried out by Gromova (fauna, 1941), Ermolova (fauna, 1978), Kimura (stone tools, 1997,2003), Turner (human teeth, 1990a), and others. The remains of two young children interred with many ornamental beads topped off the remarkable discoveries made by Gerasimov up to the time he stopped excavating in the late 1950s (Figs. 3.81-3.83). Gerasimov was a man of remarkable talents. In addition to his high-quality excavations, he was also a gifted anatomical artist. He founded the Laboratory of Plastic Reconstruction in Moscow, which still leads the world in historical and forensic facial reconstructions (Conant 2003). Work at the Mal’ta site continues to this day by Gerasimov’s student, Doctor of

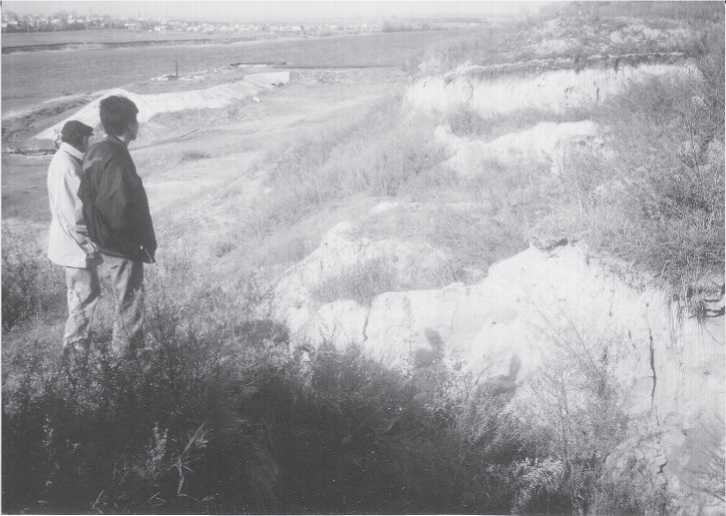

Fig. 3.75 Mal’ta-Buret’ locality. View from Mal’ta looking across Belaya River toward Buret’ village

In the distance. Originally, both archaeological sites were camps on opposite shores of a Pleistocene lake. Individuals unknown (CGT color Mal’ta 9-20-00:7).

Historical Sciences, German Medvedev, and his wife Ekaterina Lipnina (Lipnina and Medvedev 1993), also a Doctor of Science. Judging from the Paleolithic remains, the prehistoric Mal’tans were as well off economically if not better than are the modern villagers.

More than 21 000 pieces of bone were recovered in Gerasimov’s various excavation seasons. Because of inadequate storage facilities and irresponsible curation, not all of these bones have been preserved. Vera Gromova inventoried the bones collected 1928-1937. Collections made subsequently have been studied by Gromova (1941), Ermolova (1978), and Khenzykhenova and Shushpanova (2001). Fifteen species of larger mammals have been identified by these workers in the Mal’ta faunal assemblage: hare (Lepus cf. timidus), gray wolf (Canis lupus), fox (Vulpes vulpes), Arctic fox (Alopex lagopus), brown bear (Ursus arctos), wolverine (Gulo gulo), cave lion (Panthera spelaea), horse (Equus cf. caballus), rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis), mammut (Mammuthus primigenius), red deer (Cervus elaphus), caribou (Rangifer tarandus), big-horn sheep (Ovis nivicola), wild sheep (Ovis ammon), and bison (Bison proscus). No cave hyena remains have been identified, although Ovodov knows of one bone of this creature having been found not far away in the Baikal region. In addition, two kinds of pika (steppe and northern), suslik, a few kinds of small voles, even-toed lemmings, and steppe lemmings were found. Patently, this inventory of species does not reflect the complete resource base at Mal’ta, like so many other

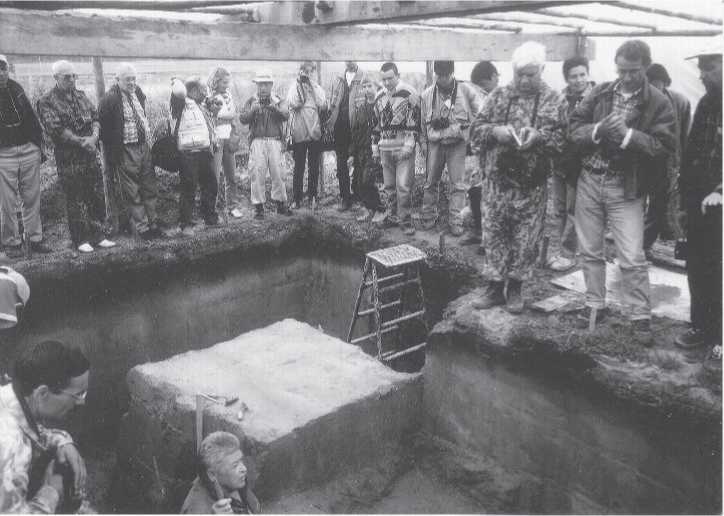

Fig. 3.76 Mal’ta site. Rain-drenched conference-goers inspect the ongoing excavation at Mal’ta.

The crowd was participating in the 2001 International Conference: Current Scientific Problems of the Eurasian Paleolithic Dedicated to the 130th Anniversary of the Discovery of the First Paleolithic Site in Russia, “The Military Hospital,” in 1871, held in Irkutsk (CGT color Mal’ta 8-4-01:9).

Fig. 3.77 Mal’ta stratigraphy. German Medvedev, in trench, explains the recent findings to the Irkutsk

Conference-goers (CGT color Mal’ta 8-4-01:18).

Fig. 3.78 Mikhail Mikhailovich Gerasimov. Copy of a photograph of the original excavator of the Mal’ta site. He later founded the Laboratory of Plastic Reconstruction in Moscow, where this photocopy was taken (original photographer unknown, CGT color LPR 1-6-81:33).

Fig. 3.79 Mal’ta artifacts. Most renowned of Gerasimov’s finds at Mal’ta are carvings of humans and birds.

The exhibit caption for these replicas in the former IHPP museum reads: “Paleolithic art: bone figurines of women fTomthe sites of Mal’ta and Buret’. Age: 20-21 thousand years. Cis-Baikal area.” Some researchers feel that one or more of the figurines has Mongoloid characteristics. However, the senior author has spent hours studying these objects and has been unable to decide if they as a group are more or less Mongoloid than Europoid. For reasons explained in the text he favors a European affiliation. Artistically they have correspondences to the Upper Paleolithic European “Venus” figurines (CGT color IHPP 6-18-87:34).

Siberian archaeological faunal inventories, because of the lack of information on bird, fish, and other potential dietary items.

Carbon-14 dates suggest a relatively short period of occupation, although there are two old outlier dates based on bone fTom Stratum 6 (43 100 BP) and “gravel” (41 100 BP). Most of the more than 15 dates tallied by Vasili’ev et al. (2002:526-527) cluster around 21000 BP - for example, 14 750±120 BP (GIN-97); 21600±170 BP (GIN-8475); 21 700 ±160 BP (OxA-619). Medvedev (1998) has proposed for various reasons, including the large amount of reindeer bone refuse, that Mal’ta was a repeatedly used, seasonally occupied, reindeer hunting camp. The Mal’ta collection is curated in the Laboratory of Archaeology, Russian Academy of Sciences, Irkutsk State University. There is an extensive literature on Mal’ta, beginning with Gerasimov and continuing to the present day: Tseitlin (1974), Kimura (2003), Medvedev (1998), Medvedev et al. (1996, 1998a, 1998b), Turner (1990a), and many others. Derev’anko et al. (1998) summarize some of this information prepared by Medvedev. The present authors visited the site together in 2000 and 2001.

Fig. 3.80 Mal’ta artifacts. Additional human figurines and birds(?). Exhibit caption reads the same as in

Fig. 3.79. One could consider these marvelous objects as examples of perimortem bone damage, but hardly in the sense of accidental damage such as cut marks or tooth scratches (CGT color IHPP 6-18-87:36).

Fig. 3.81 Location where Gerasimov found the two Mal’ta children. German Medvedev (right) stands on the spot where the two children were buried, 2 m or so below the present ground surface. Korean Paleolithic archaeologist Yung-Jo Lee takes notes (CGT color Mal’ta 8-4-01:29).

Fig. 3.82 Mal’ta teeth. Unerupted upper permanent teeth of the older Mal’ta child. Unlike the previously

Illustrated bone figurines, the dental crown morphology has proven to be more useful in racial identification. Modern European teeth are characterized by simplification, that is, weak expression or non-occurrence of several traits. Northeast Asian and all Native American teeth are just the opposite, with strong expression and frequent occurrence. The two teeth in the center of the top row are central incisors. Like European teeth these show weak (left) and no occurrence (right) of shoveling. Asians, on the other hand, have strong and frequent incisor shoveling. The tooth in the upper left is a lateral incisor. It is considerably smaller than the central incisors, a characteristic of European teeth. Asians usually have the central and lateral incisors about the same size. The upper molars in the lower row are in several ways more similar to Europeans than to Asians (CGT color IEL 1-13-81:21).

World History

World History