A number of Neolithic settlements have been excavated, particularly in Southwest Asia. The structures, artifacts, and food debris found at these sites have revealed much about the daily activities of their former inhabitants as they pursued the business of making a living. Perhaps the best known of these sites is Jericho, an early farming community in the Jordan River Valley.

Jericho: An Early Farming Community

Excavations at the Neolithic settlement that later grew to become the biblical city of Jericho revealed the remains of a sizable farming community inhabited as early as 10,350 years ago. Here, in the Jordan River Valley, crops could be grown almost continuously, due to the presence of a bounteous spring and the rich soils of an Ice Age lake that had dried up some 3,000 years earlier. In addition, flood-borne deposits originating in the Judean highlands to the west regularly renewed the fertility of the soil.

To protect against these floods and associated mudflows, as well as invaders, the people of Jericho built massive walls of stone surrounding their settlement.193 Within these walls, which were 2 meters (6H feet) wide and almost 4 meters (12 feet) high, and behind a large rock-cut ditch, which was 8 meters (27 feet) wide and 2% meters (9 feet) deep, an estimated 400 to 900 people lived in houses of mud brick with plastered floors arranged around

22Diamond, Guns, germs, and steel, p. 132.

Globalscape

Factory Farming Fiasco?

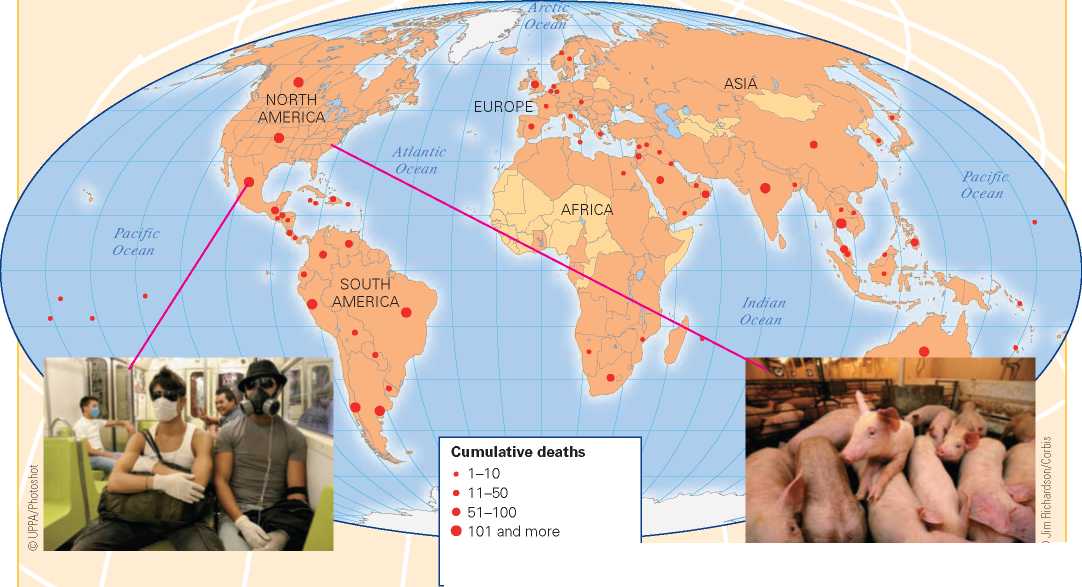

In April 2009 protective masks and gloves were a common sight in Mexico City as the news of the first cases of swine flu pandemic appeared in the United States and Mexico. On June 11, 2009, the World Health Organization (WHO) made the pandemic official, and by July cases had been reported in three quarters of the states and territories the WHO monitors. Scientists across the world are examining the genetic makeup of the virus to determine its origins.

From the outset of the pandemic, many signs have pointed to a pig farming operation in Veracruz, Mexico, called Granjas Caroll, which is a subsidiary of Smithfield Foods, the world's largest pork producer. However, Ruben Donis, an expert virologist from the U. S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, Georgia, has come to a different conclusion based on genetic analysis. According to an article in the journal Science, Donis "suggests that the virus may have originated in a U. S. pig that traveled to Asia as part of the hog trade. The virus may have infected a human there, who then traveled back to North America, where the virus perfected human-to-human spread, maybe even moving from the United States to Mexico.”® Another report has linked the current strain of swine flu to a strain that ran through factory farms in North Carolina in 1998 and to the avian flu that killed over 50 million people in 1918.194 195

While scientists examine the genetic evidence for swine flu, a look at factory farming shows how these practices facilitate the proliferation of disease. For example, the pig population of North Carolina numbers about 10 million, and most of these pigs are crowded onto farms of over 5,000 animals. These pigs travel across the country as part of farming operations. A pig may be born in North Carolina, then travel to the heartland of the United States to fatten up before a final trip to the slaughterhouses in California.

The crowded conditions in pig farms mean that if the virus enters a farm it quickly can infect many pigs, which are then shipped to other places spreading the virus further, with many opportunities for the virus to pass between species. Health risks of global food distribution have long been a concern, and the swine flu outbreak elevates these concerns to a new level.

Global Twister Do you think the swine flu pandemic should lead to changes in meat production and distribution globally?

Courtyards. In addition to these houses, a stone tower that would have taken a hundred people over a hundred days to build was located inside one corner of the wall, near the spring. A staircase inside it probably led to a mud-brick building on top. This massive wall—near mud-brick storage facilities as well as peculiar structures of possible ceremonial significance—provides evidence of social changes in these early farming communities. A village cemetery also reflects the sedentary life of these early people; nomadic groups, with few exceptions, rarely buried their dead in a single central location.

Close contact between the farmers of Jericho and other villages is indicated by common features in art, ritual, use of prestige goods, and burial practices. Other evidence of trade consists of obsidian and turquoise from Sinai as well as marine shells from the coast, all discovered inside the walls of Jericho.

Various innovations in the realms of tool making, pottery, housing, and clothing characterized life in Neolithic villages. All of these are examples of material culture.

TOOL MAKING

Early harvesting tools were made of wood or bone into which razor-sharp flint blades were inserted. Later tools continued to be made by chipping and flaking stone, but during the Neolithic period stone that was too hard to be chipped was ground and polished for tools. People developed sickles, scythes, forks, hoes, and simple plows to replace their digging sticks. Mortars and pestles were used to grind and crush grain. Later, when domesticated animals became available for use as draft animals, plows were redesigned. Along with the development of diverse technologies, individuals acquired specialized skills for creating a variety of implements, including leatherworks, weavings, and pottery.

POTTERY

Hard work on the part of those producing the food would also support other members of the society who could then apply their skills and energy to various craft specialties such as pottery. In the Neolithic, different forms of pottery were created for transporting and storing food, water, and various material possessions.

Because pottery vessels are impervious to damage by insects, rodents, and dampness, they could be used for storing small grain, seeds, and other materials. Moreover, food can be boiled in pottery vessels directly over the fire rather than by such ancient techniques as dropping stones heated directly in the fire into the food being cooked. Pottery was also used for pipes, ladles, lamps, and other objects, and some cultures used large vessels for disposal of the dead. Significantly, pottery containers remain important for much of humanity today.

Widespread use of pottery, which is made of clay and fired in very hot ovens, is a good, though not foolproof, indication of a sedentary community. It is found in abundance in all but a few of the earliest Neolithic settlements. Its fragility and weight make it less practical for use by nomads and hunters, who more commonly use woven bags, baskets, and animal-hide containers. Nevertheless, there are some modern nomads who make and use pottery, just as there are farmers who do not. In fact, food foragers in Japan were making pottery by 13,000 years ago, long before it was being made in Southwest Asia.

The manufacture of pottery requires artful skill and considerable technological sophistication. To make a useful vessel requires knowledge of clay: how to remove impurities from it, how to shape it into desired forms, and how to dry it in a way that does not cause cracking. Proper firing is tricky as well; it must be heated to over 600 degrees Fahrenheit so that the clay will harden and resist future disintegration from moisture, but care must be taken to prevent the object from cracking or even exploding as it heats and later cools down.

Pottery is decorated in various ways. For example, designs can be engraved on the vessel before firing, or special rims, legs, bases, and other details may be made separately and fastened to the finished pot. Painting is the most common form of pottery decoration, and there are literally thousands of painted designs found among the pottery remains of ancient cultures.

HOUSING

Food production and the new sedentary lifestyle emphasized another technological development—permanent house building. Because they move frequently, most food foragers show little interest in permanent housing. Cave shelters, pits dug in the earth, and simple lean-tos made of hides and tree limbs serve the purpose of keeping the weather out. In the Neolithic, however, dwellings became more complex in design and more diverse in type. Some Neolithic peoples constructed houses of wood, while others built more elaborate shelters made of stone, sun-dried brick, or poles plastered together with mud or clay.

Although permanent housing frequently goes along with food production, there is evidence of substantial housing without domestication. For example, on the northwestern coast of North America, people lived in extensive houses made of heavy planks split from cedar logs, yet their food consisted entirely of wild plants and animals, especially salmon and sea mammals.

CLOTHING

During the Neolithic, for the first time in human history, clothing was made of woven textiles. The raw materials and technology necessary for the production of clothing came from several sources: flax and cotton from farming; wool from domesticated sheep, llamas, or goats; silk from silk worms. Human invention contributed the spindle for spinning and the loom for weaving.

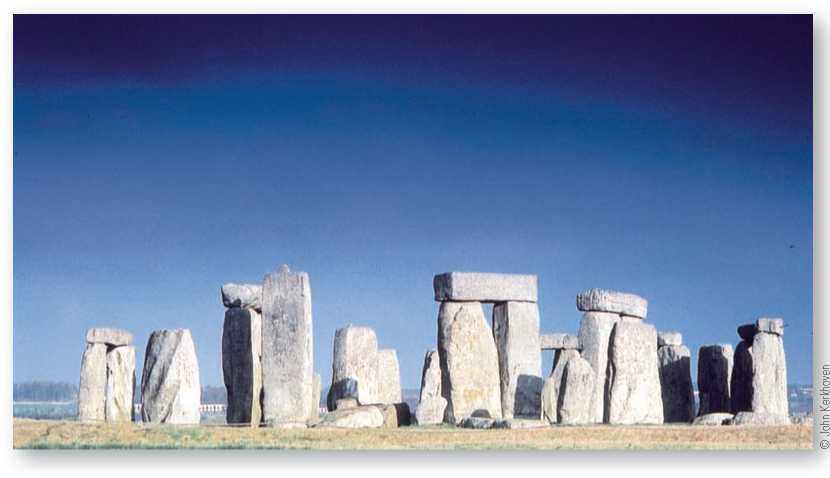

Sometimes Neolithic villagers organized to carry out impressive communal works. Shown here is Stonehenge, the famous ceremonial and astronomical center in England, which dates back about 4,500 years. Used as a burial ground long before the massive stone circle was constructed, Stonehenge reflects the builders' understanding of the forces of nature and their impact on food production. For instance, the opening of the stone circles aligns precisely so that the sunlight passes through with the sunrise of the summer solstice and with the sunset of the winter solstice. This careful alignment indicates that the people of the Neolithic were paying close attention to the movements of the sun and the growing cycle of the seasons.

Evidence of the economic and technological developments listed thus far has enabled archaeologists to make some inferences about the organization of Neolithic societies. For example, archaeological evidence reveals little in the way of a centrally organized and directed religious life, and burial sites exhibit no social differentiation. Early Neolithic graves tend not to be covered by stone slabs and rarely included elaborate objects. Burial practices tend to apply equally to all members of a community.

The small size of most villages and the absence of elaborate buildings suggest that the inhabitants knew one another very well and were even related; most of their relationships were probably highly personal ones, with equal emotional significance. Still,

Neolithic people sometimes organized to carry out impressive communal works preserved in the archaeological record, such as the site of Stonehenge in England.

From all the evidence, it seems that Neolithic societies were relatively egalitarian with minimal division of labor,

But they did develop some new and more specialized social roles. Villages appear to have been made up of several households, each providing for most of its own needs. The organizational needs of society beyond the household level were probably met by kinship groups.

World History

World History