The last two decades of investigations have enriched our understanding of Chinese Palaeolithic cultures, which used to be based solely on the Zhoukoudian and a few other sites well known in the early days. Before 1985, the focus of investigations was to discover the nature of site distributions in order to establish a Chinese Palaeolithic chronological framework. Today, the accumulated data are sufficient for us to begin interpreting issues of Palaeolithic technology and cultural materials. Until recently, studies of Palaeolithic technology in China have been limited to generalizations about the nature of lithic industries in comparison to European or other Old World localities. From the ‘chopper-chopping tools tradition’ to the ‘simple core-flake technology,’ these broad characterizations emphasized the non-Acheulean features of Early to Middle Pleistocene lithic industries in East Asian, and now seem no long valid for characterizing Chinese materials. New data suggests that the Chinese Palaeolithic technology, starting with arrival of the first hominids in East Asian around 1.7 million years ago, formed its own unique characteristics as a result of adaptive strategies to local environment. Continuity of technological development was persistent throughout the Pleistocene age until the emergence of modern humans in East Asia. The Nihewan Basin, given its resourceful landscape, was a homeland for both hominids and modern humans during the entire Pleistocene era. Although nearly 50 Palaeolithic sites were distributed across the basin, all of Early Pleistocene sites were located in clusters at the eastern end of the basin, suggesting that explorations were expanded as adaptive technology was enhanced. The technological development continued slowly but steadily; however technological variations over time can be observed in examples from Xiaochangliang and Dongguotou of the Lower Pleistocene to Shiyu and Hutouliang of the Upper Pleistocene. The similar technological continuity is suggested from lithic assemblages of Locality 1, to Locality 15, then to Upper Cave, at the Zhoukoudian area.

Cultural continuity of the Chinese Palaeolithic can also be seen in examples from southern China. Given

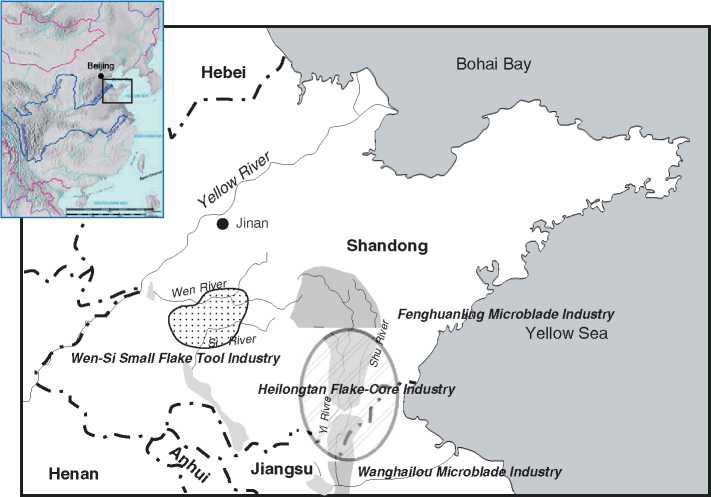

Figure 24 The Late Palaeolithic lithic industries in Shandong Penninsula during the end of the Upper Pleistocene.

The increasing numbers of archaeological sites with human fossils found in the Three Gorges/western Hubei mountainous region, this area has become a focus of research on the local evolution of anatomically modern human in East Asia. Overall material cultures from southern China remained more homogenous than in any other region.

Cultural interactions throughout the time, on the other hand, gave way to regional variations in Palaeolithic technology, as we have seen in the examples from the Luonan Basin and the Three Gorge region. In these regions, the two distinct technocomplexes between northern China (flake tools) and southern (pebble-core tools) were employed at given times but their cultural impacts were surely beyond the areas under investigation.

The most significant cultural interactions took places at the end of the Pleistocene, when western cultures penetrated into northern China and resulted in the complexity of technological manifestations. The influence of cultural interactions was expanded to parts of southern and eastern China. Our investigations in the Shandong Peninsula suggest that the Late Palaeolithic industries were more complex than we previously thought (Figure 24). Within this region, two microblade traditions (Fenghuangling and Wan-ghailou), one flake-tool tradition (Helongtan), and one small-tool tradition, coexisted in the region and there probably appeared a few large pebble-core industries at the southern end. Although we cannot at presently ascertain whether the Shandong microblade industry was an indigenous development or a foreign invention, the current evidence may be in favor of a migration mode because the Shandong microblade traditions seem to represent cultural manifestations from both the northern and southern regions.

Therefore, the formation of the Palaeolithic technology overall appears to reflect two aspects of material cultural development throughout the Pleistocene era: continuity and interaction. However, this explanation may be reinterpreted and enhanced as field investigations are ongoing. Certainly, we have much more to expect from the research results on Chinese Pleistocene archaeology in the years to come. Joint projects conducted between Western and Chinese colleagues will raise more serious questions and hopefully stimulate future investigations that, in turn, will lead to in-depth examination of the data relating to human origins and behavior in East Asia.

See also: Asia, East: China, Neolithic Cultures; Early Holocene Foragers; Japanese Archipelago, Paleolithic Cultures; Asia, South: India, Paleolithic Cultures of the South; Paleolithic Cultures; Asia, Southeast: Preagricultural Peoples; Asia, West: Paleolithic Cultures; Turkey, Paleolithic Cultures; Bone Tool Analysis; Electron Spin Resonance Dating; Europe: Paleolithic Raw Material Provenance Studies; Lithics: Analysis, Use Wear; New World, Peopling of; Paleoanthropology; Siberia, Peopling of.

World History

World History