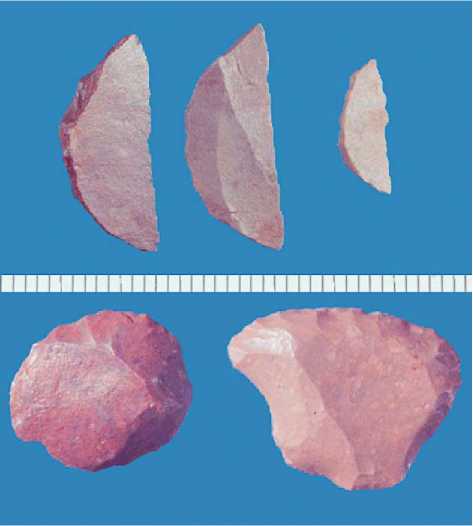

In mid-Holocene times, between about 8000 and 4000 BP, the arid central parts of South Africa were thinly populated, probably because warmer and likely drier conditions made already marginal environments unattractive. People were, however, living in the coastal areas of South Africa, in the northern parts of the country, and in Namibia, Botswana, and Zimbabwe. Stone artifact assemblages from this time are characterized by very small, highly standardized artifacts, especially tiny scrapers, and in many places, crescent-shaped ‘segments’ that may have been used in arrowheads and/or as general-purpose small cutting tools (Figure 2). The composition of assemblages changed over time (segments were especially time-restricted) but the small size of the artifacts, the relatively high proportion of retouched pieces, and a preference for fine-grained stone raw material was maintained. In the southern Cape, this tradition is called the ‘Wilton’; these assemblages extend into Namibia, Botswana, and Zimbabwe, where other names have been used. The similarity of these micro-lithic artifact assemblages over long distances shows that people subscribed to a shared set of social norms, at least as far as the accepted way to make tools was concerned.

‘Wilton’ artifacts include types very similar to items collected from recent San or ‘Bushmen’, including ostrich eggshell beads and beaded items, ostrich eggshell flasks, and bored stones used as digging stick weights, among others. Archaeologists are confident that the lifestyles of mid-Holocene foragers shared many similarities with those of people who continued to live by hunting and gathering into the twentieth century. Striking parallels have been demonstrated by David Lewis-Williams and others who have drawn

Figure 1 Map showing major geographical features of South Africa and sites mentioned in the text.

Figure 2 Microlithic ‘Wilton’ stone artefacts: segments (top) and scrapers (bottom). Scale in mm.

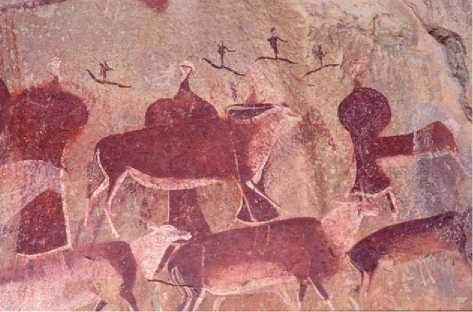

Figure 3 Rock painting from Game Pass Shelter, Drakensberg, showing eland, large cloaked figures and (at top) small running humans.

From beliefs and practices of recent San communities to gain insight into the world views expressed in the complex and often very beautiful rock paintings found in many mountainous areas of southern Africa (Figure 3). Most of these paintings have not, so far, proved amenable to direct dating, but portable cobbles with paintings on them have been recovered from excavations, and can be dated by association with the levels in which they were found. Some are more than 6000 years old. Rock-painting traditions continued into the last few centuries, as images of colonial settlers and soldiers attest.

Mid-Holocene artifact assemblages are not, however, uniform. Lyn Wadley has excavated two approximately contemporary sites in the Magaliesberg, north of Johannesburg. Jubilee Shelter yielded many standardized, formal, microlithic stone artifacts, often made from carefully chosen, fine-grained stone not available in the immediate vicinity of the site. These were found together with bone tools, ostrich eggshell beads and bead-manufacturing debris, and other items. Cave James contained a very different kind of artifact assemblage with informal tools, made mostly from local raw material, suggesting much more ad hoc manufacture. There were few nonlithic artifacts, and much less evidence of craft activities. Wadley has interpreted this difference as the result of seasonal aggregation and dispersal of hunter-gatherer groups, with formal artifact assemblages and formal rules of behavior characteristic of aggregation-phase campsites.

World History

World History