Around AD 600, changes in ceramic and lithic assemblages occurred on Puerto Rico. Rouse attributes these to the Ostionoid series that emerged from the Saladoid series. In contrast, Chanlatte Baik and others argue that the Ostionoid resulted from the interaction of the Huecan and Cedrosan Saladoid peoples with Archaic populations; others believe the Ostionoid represents a separate migration from South America; another recent argument places the origins of the Ostionoid among the Archaic cultures of Hispaniola.

By the end of the seventh century, the Ostionoid culture had expanded westward to the Dominican Republic; by the eighth century, it had spread to Grand Turk, BWI; and by the mid-ninth century, it was present in Jamaica and central Cuba. In Puerto Rico, Ostionoid culture is known from the Punta Ostiones, Maisabel, Tibes, and Bronce sites, among others, and from Paso del Indio, Puerto Rico’s deepest, best-stratified site. The Coralie site (Grand Turk), thought to be an Ostionoid colony or outpost, was occupied and reoccupied by people from AD 700-1100.

The earlier occupation represents an early, if not the first, peopling of the Bahama archipelago.

Archaeobotanical evidence indicates that Ostio-noid peoples harvested wild plants, tended or managed fruit trees, and cultivated root-tuber crops. For many years, it was argued that a dietary shift took place between the Saladoid and Ostionoid periods whereby terrestrial resources (Saladoid) were supplanted by marine resources (Ostionoid). This is also known as the crab-shell dichotomy. While zooarchaeological and carbon isotope evidence is contradictory, it is generally agreed that where such subsistence change is observed, local factors are responsible and that marine resources contributed significantly throughout both periods. Guinea pigs, recovered from several sites, including Tibes, represent a faunal import from South America.

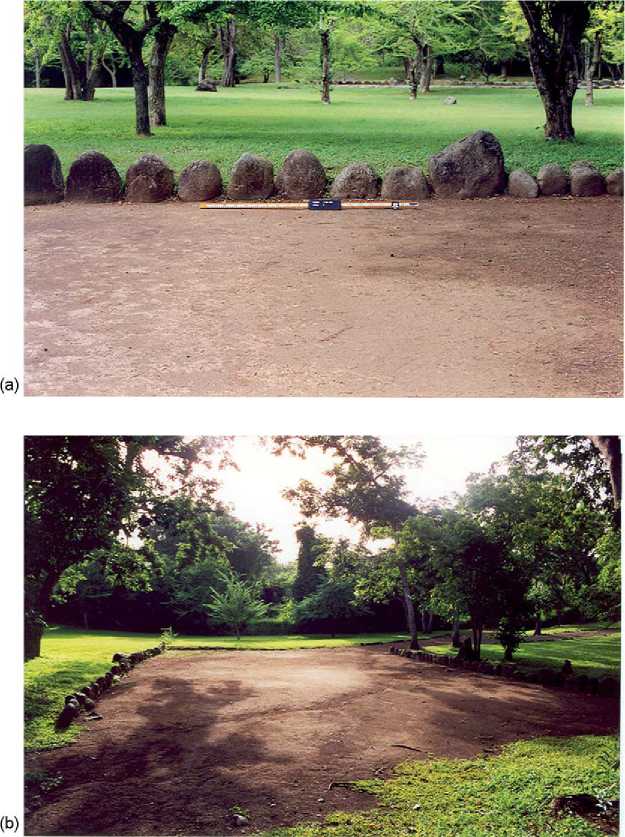

Terracing and raised fields (montones) are found during this time period in Puerto Rico. People established settlements in new areas; in some regions, residences decreased in size, suggesting that they were occupied by nuclear families. On the eastern side of Puerto Rico, there is evidence of centralized settlement patterns. Civic-ceremonial and ballcourt sites, mostly in the southeastern part of the island, appear. There is also an increase in the number and size of zemls. Architectural settlement and artifact changes are believed to relate to the emergence of institutionalized social hierarchy. Tibes (Figure 7) is the oldest civic-ceremonial and possibly the first prehistoric political center in the Caribbean. Located in south-central Puerto Rico, it contains nine ballcourts, three dance plazas, causeways, and residences believed to have been occupied by emerging elites. Anadenanthera sp. wood and seeds of evening primrose (Oenothera sp.), a mild narcotic, were both found dating to the ceremonial occupation. Anadenanthera sp. is one of the possible sources of cojoba, the primary hallucinogenic substance used by the Taino to induce visions. This is the earliest archaeological evidence of the plant in the Caribbean.

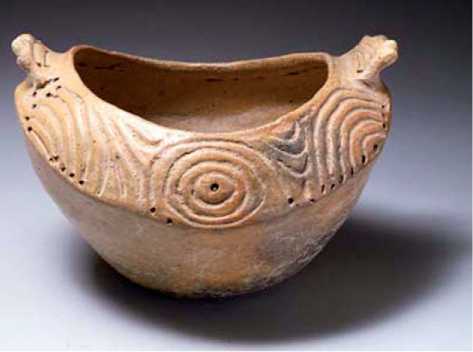

Ostionoid pottery consists of red-slipped boatshaped, straight-sided, and open vessels that often contain loop handles, sigmoid appliqueis, and simple modeled head lugs (Figure 8). Red paint and black smudging on vessel exteriors is sometimes present. New kinds of flaked stone tools and different methods of tool production also differentiate the Ostio-noid from the Saladoid. The people also made stone and shell artifacts with anthropomorphic and zoo-morphic images.

Sometime during the AD 600s, another pottery subseries, the Meillacan Ostionoid, emerged in the Cibao Valley of northern Hispaniola and is believed to represent an in situ development from the Ostionoid.

Figure 7 (a) Central section of the southern stone row of the main plaza of Tibes (Structure 6). Ball Court 2 is visible in the background. Puerto Rico. Photograph courtesy of L. Antonio Curet. (b) Ball Court 1 of Tibes facing east. Puerto Rico. Photo courtesy of L. Antonio Curet.

Figure 8 Ostionan Ostionoid boat-shaped vessel with strap handles. Puerto Rico. Ceramic. Height: 41; width: 32; thickness: 21.1 cm. Museo de Historia, Antropologfa y Arte, Universidad de Puerto Rico.

Contrasting views suggest, though, that the Meillacan diffused from the Guyana Highlands, that it emerged centuries earlier from the Punta Cana tradition of eastern Dominican Republic (see below), and that it is unrelated to the Ostionoid series. The Meillacan and Ostionan cultures overlapped temporally in the Turks and Caicos and elsewhere; moreover, Ostionan pottery has been found in association with Meillacan sherds at sites in Hispaniola, suggesting that the latter did not necessarily supplant the former.

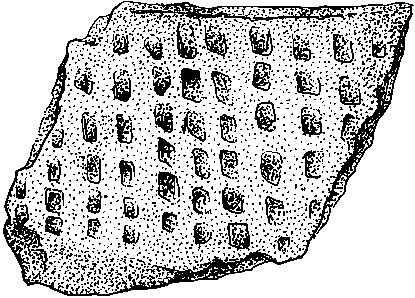

Meillacan pottery is thin, hard, and unpainted. Decorations include modeling, punctuation (Figure 9), zoned incision, and anthropomorphic and zoomor-phic applique figures located on the shoulder or rims of hemispheric and boat-shaped vessels. Some argue

Figure 9 Meillacan Ostionoid sherd with punctation. Illustration courtesy of Mary Jane Berman.

Figure 10 Chican Ostionoid bowl. Dominican Republic. Ceramic. Height: 14; width: 20.6; thickness: 18.7 cm. Collection of El Museo del Barrio, gift of Brian and Florence Mahony. El Museo del Barrio, New York City (PC92.1.4). Photograph by Bruce Schwarz.

That Meillacan ceramic decoration drew upon Courian Casimiroid stone work designs; such an argument lends support that the Meillacan were direct descendants of Archaic cultures, with no links to the Ostionoid or represents the merging of Archaic and Ostionoid cultures.

Meillacan ceramics or local versions with Meillacan designs appear almost contemporaneously in the ninth century in the Dominican Republic, Jamaica, eastern and central Cuba, and the central Bahamas. A combination of exploration, colonization, and high levels of interisland interaction (trade, exchange) is likely responsible for the extensive spread of the Meillacan style. The earliest evidence of Palmetto ware, a locally made Bahamian pottery with Ostionan and Meillacan traits, signifies the appearance of a distinct Lucayan culture at AD 700-900 at the Three Dog and Dune #2, Pigeon Creek sites on San Salvador Island. Ceramic assemblages from northern and eastern Cuba exhibit both Meillacan and Ostionan traits, as does the White Marl pottery of Jamaica.

Meillacan peoples and people influenced by Meillacan culture practiced root crop and seed horticulture in home gardens and mounded fields, tended or managed fruit trees, gathered wild plants, and fished and collected shellfish from marine and estuarine waters. Starch grain analysis on chert microliths from the Three Dog site has revealed evidence of maize, chili peppers, and several root and tuber crops, suggesting that the peoples who settled the central Bahamas brought these plants with them from their homelands in Hispaniola and Cuba (see Starch Grain Analysis).

Sites in the Bahamas, Cuba, and Jamaica are small, reflecting the activities of horticultural-fishing groups. Meillacan outposts, including specialized shell bead production sites, were established on Middle Caicos and Grand Turk, BWI. The Meillacan culture did not penetrate Puerto Rico.

Around AD 800, a new pottery, Chican Ostionoid, emerged in the southeastern Dominican Republic. By AD 1200, this ceramic style and its regional variants became widespread in Hispaniola (except for the southwestern peninsula), Puerto Rico, Jamaica, the Turks, and Caicos, and ultimately eastern Cuba, which the Chican peoples settled in (approximately) AD 1450. It has been argued recently that Chican pottery, like Meillacan pottery (see above) can also be traced to Punta Cana pottery due to resemblances in decorative characteristics. According to this argument, the Meillacan and Chican traditions are unrelated to the Ostionoid and should be referred to by their own series (rather than subseries) names (Meil-lacoid, Chicoid).

World History

World History