Karen Frifelt and Per Sorensen, pp. 15-48, London, 1989. Includes basic archaeological/historical information for the Oman peninsula before tlie Islamic period.

Costa, Paolo M. “The Study of tlie City of Zafar (al-Balid).” Jotmta/ of Oman Studies 5 (1979): 111-150, Early work at Dhofar.

Edens, Christopher. “Towards a Definition of the Western ar-Rub’ al-Khali ‘Neolithic.’”6 (1982); 109-124.

Edens, Christopher. “Archaeology of the Sands and Adjacent Portions of the Sharqiyah.” Journal of Oman Studies Special Report 3 (198SA):

113-130.

Edens, Christopher. “The Rub al-Khali ‘Neolitliic’ Revisited: The View from Nadqan.” In Araby the Blest: Studies in Arabian Archaeology, edited by Daniel T. Potts, pp. 15-43. Carsten Niebuhr Institute Publication, 7. Copenhagen, 1988B.

Frifelt, Karen. ‘“Ubaid in the Gulf Area.” In Upon This Foundation: The 'Ubaid Reconsidered, edited by Elizabeth F. Henrickson and Ingolf Thuesen, pp. 404-417. Copenhagen, 1989.

Frifelt, Karen. The Island of Umm an-Nar, vol. i. Third Millennium Graves. Aarhus, 1991.

Frifelt, Karen, ed. The Island of Umm an-Nar, vol. 2, The Third Millennium Settlement. Moesgaard, 1995.

Grohmann, Adolf. “Suhar.” In Encyclopaedia of Islam, pp. 544-547, Leiden, 1934.

Groom, Nigel. “Oman and the Emirates in Ptolemy’s Map.” Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy S (i994): 198-214.

Haerinck, E. “Heading for the Straits of Hormuz, an Ubaid Site in the Emirate of Ajman (U. A.E.).” Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy 2 (1991): 84-90.

Hoch, Ella. “Reflections on Prehistoric Life at Umm an-Nar (Trucial Oman) Based on Faunal Remains from the Third Millennium B. C.” In South Asian Archaeology 1977, edited by Maurizio Taddei, pp. 589-638. Naples, 1979.

Hoch, Ella. “Animal Bones from the Umm an-Nar Settlement.” In The Island of Umm an-Nar, vol. 2, The Third Millennium Settlement, edited by Karen Frifelt, pp. 249-256. Moesgaard, 1995.

Kervran, Monik, and Frederik T. Hiebert. “Sohar pre-islamique: Note stratigraphique.” Internationale Archaologie 6 (1991): 337-348.

McClure, Harold A. “A New Arabian Stone Tool Assemblage and Notes on the Aterian Industry of North Africa.” Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy 5 (1994): i-i6.

Miroschedji, Pierre de. “Vases et objets en steatite susiens des Musee du Louvre.” Cahiers de la Delegation Archeologique Franfaise en Iran 3 (1973): 9-79-

Nayeem, Muhammad Abdul. Prehistory and Protohistoiy of the Arabian Peninsula, vol. i, Saudi Arabia. Hyderabad, 1990. Oman in the larger context of tlie Arabian Peninsula.

Nisbet, Renato. “Evidence of Sorghum at Site RH5, Qurm, Muscat.” East and West 35 (1985): 415-417.

Oppenheim, A. Leo. “Seafaring Merchants ol Ur." Journal of the American Oriental Society 74 (1954): 6-17.

Potts, Daniel T. The Arabian Gtdf in Antiquity. 2 vols. Oxford, 1990, passim. Offers basic historical/archaeological information about the Oman peninsula before the Islamic period.

Potts, Daniel T. “The Chronology of the Archaeological Assemblages from the Head of the Arabian Gulf to tlie Arabian Sea, 8000-1750 B. C.” In Chronologies in Old World Archaeology, vols. 1-2, edited by Robert W. Ehrich, pp. 63-76, 77-89. 3d ed. Chicago, 1992.

Potts, Daniel T. “The Late Prehistoric, Protohistoric, and Early Historic Periods in Eastern Arabia, ca. 5000-1200 B. C.” Journal of World Prehistoiy 7 (1993): 163-212.

Pullar, Judith. “Harvard Archaeological Survey in Oman, 1973,1: Flint Sites in Oman.” Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies 4

Oman.” Journal of Oman Studies i (1975): 49-88. Includes early work at Dhofar.

Tosi, Maurizio. “The Emerging Picmre of Prehistoric Exahia." Annual Review of Anthropology 15 (1986): 461-490. Oman in tlie larger context of tlie Arabian Peninsula.

Uerpmann, Margarethe. “Some Remarks on Late Stone Age Industries from the Coastal Area of Northern Oman.” In Oman Studies, edited by Paolo M. Costa and Maurizio Tosi, pp. 169-177. Serie Orientale Roma, vol. 63. Rome, 1989.

Weisgerber, Gerd. . . und Kupfer in Oman.” Der Anschnitt 32 (1980): 62-no.

Weisgerber, Gerd. “Mehr als Kupfer in Oman-Ergebnisse der Expedition 1981.” Der Anschnitt 33 (1981): 174-263.

Wilkinson, John. “Suhar in the Early Islamic Period and the Written Evidence.” In South Asian Archaeology 1977, edited by Maurizio Taddei, pp. 887-907. Naples, 1979.

Williamson, A. Sohar and Omani Seafaring in the Indian Ocean. Muscat, 1973-

Zarins, Juris, et al. “The Second Preliminary Report on the Southwestern Province.” Atlal 5 (1981): 9-42.

Zarins, Juris. “The Early Rock Art of Saudi Arabia.” Archaeology 35 (1982): 20-27.

Zarins, Juris, et al. “Preliminary Report on the Archaeology Survey of the Riyadh Area.” Atlal 6 (1982): 25-38.

Zarins, Juris. “Obsidian and the Red Sea Trade; Prehistoric Aspects.” In South Asian Archaeology 1987, edited by Maurizio Taddei, pp. 507-541. Rome, 1990.

Zarins, Juris. “Dhofar, Franldncense, and Dilmun: Precursors to the lobaritae and Omani.” Paper presented at the Interdisciplinary Archaeology Conference, Harvard University, 15 October 1994 (to be published in 1995).

Zarins, Juris. “Preliminary Results of the Trans-Arabia Expedition to Dhofar, 1992-1995.” Paper to be published in the proceedings of the conference “Profumi d’Arabia,” Pisa, Italy, 18-22 October 1995.

Juris Zarins

ONOMASTICS. See Names and Naming.

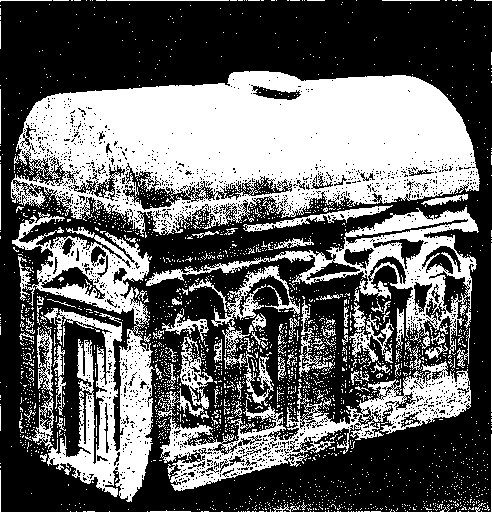

OSSUARY. A small chest or box, usually made of stone but occasionally of clay or wood, used for reburying human bones after the flesh has decayed, is Imown as an ossuary. It was used with some frequency in the Early Roman period in Jewish tombs in the vicinity of Jerusalem.

A typical ossuary from that period is hollowed from a single block of limestone and measured about 60 X 35 X 30 cm; tliere were smaller ossuaries for children. It had a removable lid that might be flat, rounded, or gabled. Most ossuaries were plain, but many were decorated with motifs typical of Jewish art of the period: geometric designs (e. g., tire six-petaled rosette) or representations of Jewish architectural and religious tliemes (e. g., tomb monuments or palm branches). (See figure i.) Often only one long side of the ossuary was decorated and professionally incised by chip carving. Inscriptions, by contrast, were not professionally done but were scrawled with charcoal or scratched with a sharp object almost anywhere on the ossuary—on its sides, ends, lid, or even along a top edge. Written in Greek, Ara-

188 OSTEN, HANS HENNING ERIMAR VON DER

OSSUARY. Figure I. From Mt. Scopus, first century

BCE. (Courtesy ASOR Archives)

Maic, or Hebrew, ossuary inscriptions identify the deceased by name, only occasionally adding details about family relations, place of origin, age, or stains.

The deceased was initially laid in a niche or on a shelf to decompose in a family burial cave. When decomposition was complete, the bones were gathered in ossuaries for secondary burial and placed in a niche, on a shelf, or in a separate chamber (e. g., in the family tomb located on Rehov Ruppin in Jerusalem, in the “Goliath” tomb in Jericho, and at Dominus Flevit, a first-cenmry cemetery on tlie Mount of Olives). The bones of more than one individual could by custom be placed in the same ossuary: according to the tliird-century rabbinic document Semahot 13.8, persons who shared a bed in life could share an ossuary in death. Even the “Caiaphas” ossuary contained the bones of more than one person. The Caiaphas ossuary is a large (74 X 29 X 38 cm) richly ornamental ossuary with a vaulted lid inscribed on the side and back with the name “Caiaphas.” This name also belonged to the High Priest during the days of Jesus (Mt. 26:57). The ossuary was found in 1990 in a tomb located in Nortlt Talpiyot, a southern suburb of Jerusalem.

The historical development of Jewish ossuaries is still debated. Eric Meyers sees tltem as an adaptation of tlie longstanding ancient Near Eastern custom of secondary burial, with parallels in Chalcolithic bone containers, Cretan lar-nakes, and Persian astodans. L. Y. Rahmani argues, however, that Jewish secondary burial in ossuaries was unique to Jerusalem in the Early Roman period. Rachel HachUli and Amos Kloner have in turn questioned Rahmani’s view.

They note several finds of Jewish ossuaries at locations quite distant from Jerusalem as late as the fourth century CE. Kloner cites tlie finds at Horvat Tilla, in the southern She-phelah, in particular. Although there presently is no scholarly consensus, ossuaries can reasonably be regarded as the form of secondary burial tltat was most popular among Jews living near Jerusalem in the Early Roman period.

It is widely agreed (based on literary evidence from the Mishnah and tlie two Talmuds) that Jewish secondary burial in ossuaries was driven by two theological beliefs: resurrection of the body, and expiation of sin via tlie decomposition of human flesh. The former motivated the use of an individual burial container and the latter the practice of secondary burial. For Palestinian Jews in the Roman period, bones tltat had been placed in an ossuary were purified from sin and ready for tlie resurrection.

[5ee also Burial Techniques; Jerusalem; Sarcophagus.]

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Figueras, Pau. Decorated Jewish Ossuaries. Leiden, 1983. Brief intro-ductoiy study with many useful diagrams and photographs. Greenhut, Zvi. “The ‘Caiaphas’ Tomb in North Talpiyot, Jerusalem.” ‘Atiqotii (1992); 63-71. Exemplary report from a recent e.cavation of a tomb containing ossuaries, including one marked with the name Caiaphas.

Hachlili, Rachel. Ancient Jewish An and Archaeology in the Land of Israel. Leiden, 1988. The most thorough presentation of HacWili’s perspective on Jewish ossuaries, based on her tomb excavations at Jericho.

Meyers, Eric M. Jewish Ossuaries: Reburial and Rebirth. Rome, 1971. Early attempt to relate Jewish ossuaries to tire wider context of ancient Near Eastern practices of secondary burial. Rahmani’s unnecessarily harsh review may be found in Israel Exploration Journal 2'i.2 (1973): 121-126.

Rahmani, L. Y. “Ancient Jerusalem’s Funerary Customs and Tombs.” Biblical Archaeologist 45.1 (1982): 43-53; 45.2 (1982): 109-119. Brief and readable summary of Rahmani’s view that ossuaries are “uniquely Jerusalemite.”

Byron R. McCane

World History

World History