In Britain and in parts of Continental Europe, there is a consistent and repeated ritual activity which associates animal burials with pits, wells or shafts. Most striking is the behaviour of Iron Age communities in southern England, who used pits dug into the chalk for the storage of grain. What seems to have happened is that once a pit came to the end of its useful life and was no longer required, elaborate, pre-closure thanksgiving ceremonies took place, indicated archaeologically by the deposition of whole or parts of animals. This act of burial was a nonrational act, involving a serious economic loss, as we have seen, but it was none the less repeated in many pits and on a number of sites in southern Britain. The animals, often known as 'special deposits', were usually positioned, sometimes very carefully, at the bottom of pits before they were finally filled with rubbish and soil. Pits containing

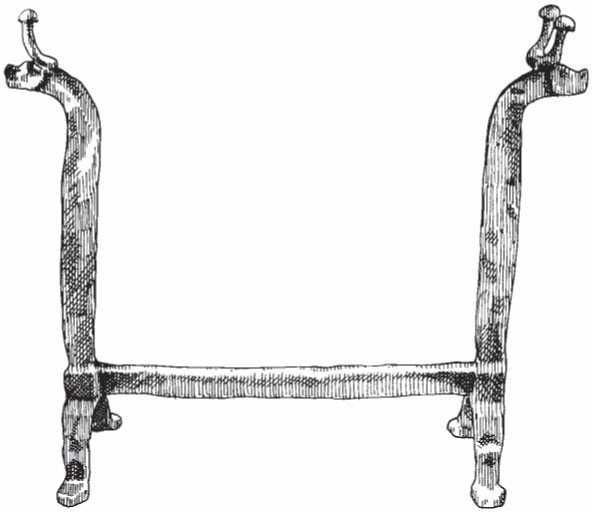

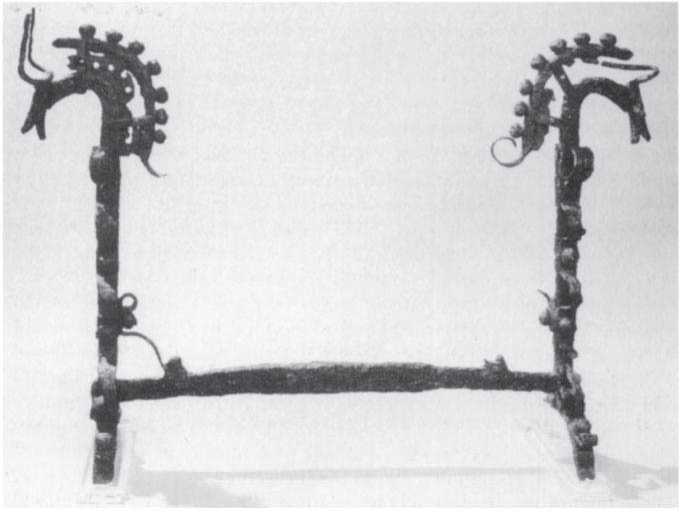

Figure 5.6 First-century BC or early first-century AD iron firedog found in a grave at Baldock, Hertfordshire. Paul Jenkins.

'special deposits' are always situated in the interior of occupation sites, rather than on the periphery. Through time there is a shift in the type of site in which such pits occur: thus in later periods, the 'special deposits' of animal burials decline in open settlements but increase sharply in the hillforts.34

The special or abnormal deposits of animals in pits fall into three main categories: they may consist of complete or partial articulated skeletons, bearing no signs of butchery for consumption, and sometimes beheaded; or they may be represented by skulls, which were not split to extract the brain, as was the normal economic practice; or they may comprise articulated limbs. In all three groups, the remains represent the loss to a community of the normal economic benefits of animals, whether for consumption, for animal products or for breeding. This loss was deliberate and presumably reflects valuable offerings to the gods.

The animals which were sacrificed in this manner were nearly always domestic species or birds. An exception occurs at Winklebury (Hants), where a deposit of twelve foxes and a red deer was laid down. There are a number of reasons for these 'special deposits' to be considered abnormal and therefore arguably the result of ritual activity: one is the absence of evidence for consumption, in the form of butchery; another is that the animals represented by special deposits do not accurately reflect their proportions in the general animal population: thus horses are overrepresented, sheep underrepresented, and so on. A third reason is the presence of multiple burials, where two or more complete animals were interred together. It is surely too much of a coincidence to suppose that the animals died naturally at the same time, and deliberate sacrificial slaughter is a much more persuasive explanation.35

It is worth while to examine these 'special deposits' in British grain-storage pits in a little more detail. Whilst much of the current and recent research has been stimulated by the excavations at the Danebury hillfort (Hants), occurrences at other sites in southern Britain indicate that animal burials in pits were a recurrent phenomenon. Whole skeletons were present, for instance, at Ashville (Oxon.) and Maiden Castle (Dorset); skulls at Meon Hill (Hants) and Camulodunum (Essex). At Twywell (Northants) two pigs and a dog were buried together; a dog and a man at Blewburton (Oxon.). Several times at Danebury, dogs and horses were interred together, and on one occasion a cat and a sheep shared a pit.

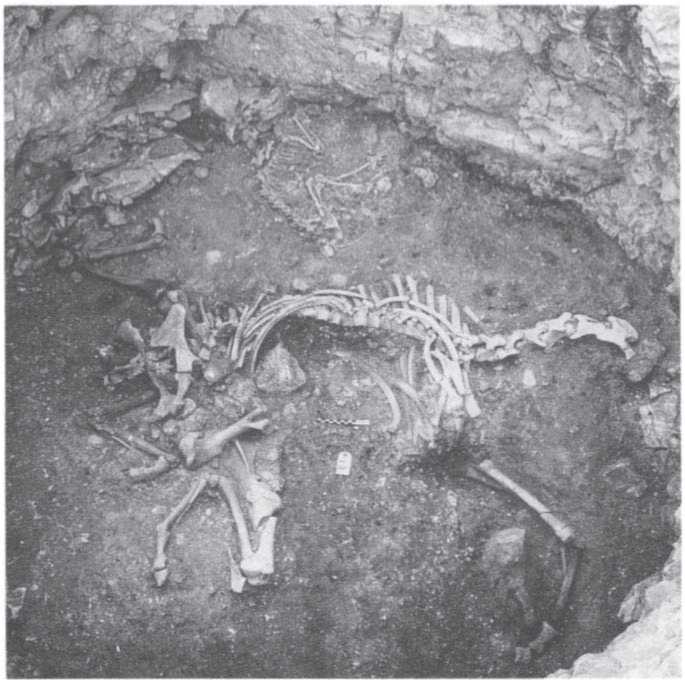

Danebury is particularly rich in animal remains and it is this site which has provided the greatest opportunity to study the curious ritual activity reflected by special animal deposits. The pits at Danebury are narrow-mouthed, flaring out at the base.36 About one-third of the pits contain special deposits of animals (figure 5.7). It may be, however, that some of the others may once have contained organic offerings - grain, slices of meat, vegetables or liquor - which have vanished, leaving no archaeological trace. Certainly, some pits contained iron tools, which were themselves arguably offerings. The very high proportion of special animal deposits at Danebury is in part due to the exceptionally large number of bones yielded by the site altogether.37 The ritual associated with pits and animals may be quite elaborate: in an early pit, dating to before the defended enclosure was erected (i. e. pre-500 BC) were two dogs, associated with other bones, which were covered with chalk blocks.38 In another, later, pit were an eviscerated horse and a pig, again associated with large blocks of chalk. Several of the animal bodies at Danebury were found with stones and slingstones, used for defending the stronghold in time of war. Annie Grant has suggested that, although many deposits of domestic beasts reflect a considerable economic loss to the community, there may none the less have been economic considerations at work.39 Thus, whilst sheep are the most important secular commodity at Danebury, these animals appear relatively rarely as special pit-deposits. Conversely, horses and dogs occur with relative frequency as ritual burials, even though they are of less economic importance. What Grant suggests is that it may have been precisely

Figure 5.7 Ritual burial of a horse and a dog in a disused Iron Age grain-storage pit, Danebury, Hampshire. By courtesy of the Danebury Trust.

Because these animals were less significant as food that they were singled out for use as special offerings to the gods. Indeed, where there are partial animal burials, it may be argued that only part of an animal carcase was sacrificed and the other part was consumed, thus allowing gods and humans to share the largesse.

To understand the placing of offerings in storage pits, it is perhaps helpful to think of corn storage itself as, in a sense, a ritual or religious act, whereby the grain was given into the safe-keeping of the chthonic or underground gods. Thus it is quite comprehensible to envisage thank-offering ceremonies taking place before a disused pit was finally closed. Such a ritual act would be at one and the same time one of gratitude, appeasement and a rite of passage at a time of change. What we seem to be witnessing is the manifestation of a magico-religious belief associated with animal husbandry, in which the gods were thanked for protecting the corn by means of fertility-offerings symbolic of the renewal of the earth. The animals which rotted in the ground, their blood and vital juices seeping into the earth, nourished the earth-gods in whose territory the pits were dug. Storage in pits was a very efficient method of keeping corn dry and vermin-free, unspoilt and ungerminated. This efficiency was acknowledged with gratitude as being of divine origin.

In addition to the discrete phenomenon of grain-storage pit ritual in central-southern England, there is evidence in Iron Age and Romano-Celtic Britain that shafts and wells were also sites of ritual activity involving animals.40 These vary through time: for instance, bird deposits are particularly important in Iron Age shafts, pigs in pits belonging to the Romano-Celtic phase. In the Iron Age, the shafts tended to be deeper, more indicative of careful, systematic ritual deposition. The votive offerings which they contained are connected with perceptions of natural and domestic fertility.41 In the Roman period, wells are particularly associated with dogs: at the Romano-British town of Caerwent, the tribal capital of the Silures, five skulls were placed in a well; numerous dogs were cast into a deep well associated with a shrine of the first century AD at Muntham Court (Sussex); and the remains of sixteen dogs, together with a complete Samian bowl, were placed in a second-century well at Staines near London.42 It is very probable that dogs were linked with some chthonic or underworld ritual (see pp. 111-13). Bird remains in wells are interesting: most curious of all is the deposit of ravens or crows set between pairs of tiles at Jordan Hill, Weymouth, a dry well associated with a Romano-Celtic temple.43

Ritual pits as sacred places for animal-burial occur in Continental as well as in British contexts. The Czechoslovakian site of Libenice is a long, subrectangular enclosure dating to the third century BC. Inside was a central pit containing a standing stone and several pestholes; devotees descended into the pit at the time of feasting by a stairway, and performed animal sacrifices. Before each ceremony, the bottom of the sunken structure was carefully prepared and a layer of earth spread out. It is thus possible to count the number of sacrifices which took place on successive occasions: there were twenty-four. The sanctuary seems finally to have been destroyed by fire.44 The oppidum of Liptovska Mara was another cult site in Czechoslovakia, where the sacral activity was focused on a large pit containing burnt remains of domestic animals, associated with pottery, jewellery and carved wood. This sacred site dates to the middle to end of the first century BC.45

In Gaul, a number of sites have yielded evidence of animal ritual involving pits. In Aquitaine, deep pits of the mid-first century BC contained cremations and animal bones, including those of toads. In Saint Bernard (Vendee) one shaft contained the complete trunk of a cypress, antlers and the figurine of a goddess.46 The vicus or civil settlement at Bliesbruck (Moselle), which was occupied during the first to third centuries AD, contained hundreds of holes and pits filled with layers of 'offerings', including remains of animals, attesting to ritual behaviour. The pits were all lined with stones and their sole apparent purpose was to receive sacrificial deposits. Unlike the southern British pits discussed earlier, they had no overt primary function but seem to have been constructed as a religious act. Each pit contained several thousand bones, which fall into two groups: some were the result of ritual feasting, shown by their being thrown into ashy earth full of charcoal, along with other material. The second group of bones was deposited in a structured, ordered manner and represents the joints of meat, articulated bones, heads or complete bodies of animals offered to the presumably chthonic deities of the land.47 Many of the meat-offerings at Bliesbruck seem to have been the less palatable parts of the animal, particularly the spinal columns, implying once again that the choice pieces were consumed by humans in ritual feasting. By contrast, groups of sacred pits at Argentomagus (Indre) contain the best portions of meat - shoulder and leg joints.

One of the most interesting series of pits on Gaulish sites is a group found within the sacred space of Gournay (Oise). Here, Jean-Louis Brunaux excavated nine pits grouped in threes and a larger pit which was constructed to receive the carcases of sacrificed oxen, which were left there for six months or more to decompose before being placed on either side of the sanctuary entrance, in an apotropaic, guardianship ritual (figure 5.4). This kind of burial is interpreted by Brunaux as a chthonic and fertility ritual, perhaps similar to that represented by the 'special deposits' of southern England, in which an animal was received into the earth to nourish it.48

Graves

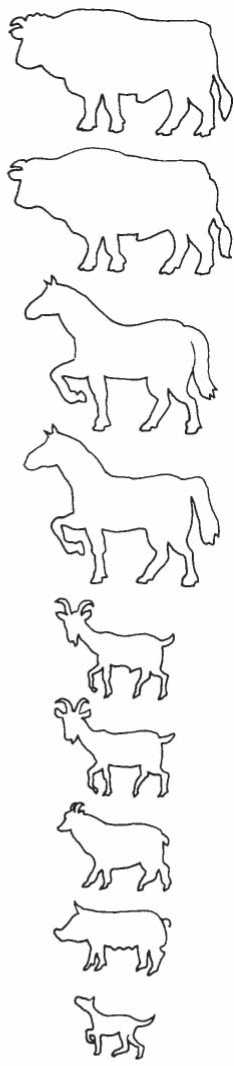

In the middle of the first century BC Julius Caesar refers to a burial rite which he had heard of in Gaul but which he describes as being before his time and obsolete at the time of writing:49 he comments that it used to be the case that, when a man was buried, all his possessions, including his dependants and animals, were placed on his funeral pyre. There is occasional archaeological evidence to support this, at least in part. In the King's Barrow, an Iron Age chariot-burial in east Yorkshire, a Celt was interred with his dismantled vehicle and accompanied by the horse team itself.50 At Soissons, two cart-burials appear to have been accompanied by entire funeral corteges, comprising the complete bodies of horses, bulls, goats, sheep, pigs and dogs (figure 5.8).51 Annie Grant points to a comparative sepulchral ritual which took place in the Kerma

Figure 5.8 The funeral cortege of animals found accompanying the Iron Age chariot-burial at Soissons, France. Paul Jenkins, after Meniel.

Culture of prehistoric Nubia, at around 2500 BC.52 Here animals were central to funerary ritual and entire, sacrificed animals - mainly sheep - were placed in the tombs, together with joints of mutton, thus differentiating between food for a feast or for the dead man and offerings to the gods.

Generally speaking, the animal remains which occur in graves are there for one of a distinct set of reasons. First, they may reflect funerary feasting, in honour of the dead and the gods associated with death. Second, parts of animals appear in graves as food-offerings, accompanying the dead to the Otherworld, either as sustenance, to keep him going on his long journey, or perhaps as payment to the under-world powers, a kind of entrance-fee for admittance to the Otherworld. A third group of animal remains consists of ornaments where, for instance, animal teeth may be perforated to form part of a collar or necklace. The appearance of just one bone of an animal may be present to symbolize the whole animal: such may be the case with the phalange of an aurochs at Mont Trote or the talus of an ox at Rouliers. Finally, some animals, like dogs or horses, may be present in the grave to accompany their master to the afterlife.

It is frequently difficult to make a distinction between food-offerings to the dead and remains of ritual feasting. Many Iron Age chariot - or cart-burials contain one or more joints of pork which show no signs of having been eaten. In the fifth to third centuries BC, Gaulish warriors were sometimes interred in rectangular graves with cuts of meat which remains of funerary banquets, the food-offerings themselves often seem were usually positioned at either end of the tomb.53 In comparison with rather modest; good cuts of meat were not all that common. Other offerings to the dead, such as pottery, seem often to have been more important than actual food-offerings. Sometimes there is evidence that particular species, ages and cuts of meat were necessary to a specific rite in a certain community. Thus, cemeteries in the Ardennes, such as Mont Trote and Rouliers, contain food-offerings for the deceased which consist mainly of young animals.54 Sometimes indifferent cuts of meat, like spinal columns, might be offered together with one good portion, perhaps an upper leg. Some offerings consist of a single piece of meat, others several pieces or articulated limbs. At the cemetery of Epiais-Rhus in the Paris Basin, changes in the traditions of food-offerings may be observed through time. In the free Gaulish period, pigs were favoured, but in Gallo-Roman graves, domestic fowls were more popular. At Tartigny (Oise) there were different combinations of animals in each of the five graves,55 but the youth of animals such as pigs is a consistent factor in their choice. Sometimes the bodies of the animal offerings appear to have been treated in a curious way: at both Mont Trote and Rouliers in the Ardennes, pigs were interred with three out of four feet missing.56 The absence of feet and lower limbs in some

Graves suggests that animals were flayed, the extremities being removed with the skin.

The main activity associated with animal ritual in Gaulish graves seems to have been linked with funerary feasting. There was butchery and cooking at Mont Trote and at Rouliers.57 Pork and lamb were offered to both the dead and the bereaved at the ritual banquet. The food refuse from many cemeteries paints a picture of perhaps ostentatious ceremonies where vast quantities of young, succulent pigs and lambs were consumed and the bones tossed with apparent abandon into the grave.58 Burials of the later Iron Age in the Champagne region contain remains of both ritual meals and food-offerings: complete skeletons are rarer than single bones or articulated limbs, and wild animals are very seldom attested.59

The so-called 'symbolic' remains of animals in graves are interesting: at Tartigny, one grave contained a hare, a one-year-old dog and the mandible of a horse 8 years old. This could be interpreted as a hunter's grave (with prey and hunting-animals represented), and it is espcially interesting that the jaw alone could represent the entire horse.60 What happened to the rest we can only speculate: perhaps the animal was eaten. Likewise, the digit of an ox or the tooth of a bear might represent, symbolically, the whole beast (see chapter 3). Other symbolism may be present in the graves: the Romano-British cemetery at Skeleton Green (Herts.) was in use in the late first century to early second century AD. The burials here were cremations and they were accompanied by animal remains. Whilst the deposits could simply reflect food-offerings, there is something curious about their organization within the cemetery, in that - as we have seen - male animals were associated specifically with the burials of men and birds with women, whilst sheep accompanied both sexes.61 This kind of evidence leads us to believe that there may sometimes have been elaborate and symbolic ritual whose meaning it is difficult for a modern enquirer to comprehend.

Sanctuaries

Animals were central to Celtic religion because of their importance in daily living. Sacred animals are dominant in Celtic imagery (see chapters 6, 8), and this preoccupation with the animal world is mirrored by sacrifices and rituals in holy places, in the sanctuaries where the Celts communed with the supernatural world. Shrines are especially good sites for learning about man-animal relationships. As is the case with sepulchral remains, animal deposits in shrines consist of both creatures which were consumed and those which were not. The former were once again apparently the remnants of ritual feasting, a time for conviviality between gods and humans. The latter were left for the inhabitants of the spirit-world to enjoy.

Many animal bones in sanctuaries bear signs of butchery and culinary preparation by the individuals worshipping there. Gaulish shrines such as Mirebeau (Cote d'Or), Ribemont sur Ancre (Somme) and Digeon (Somme) all contain such evidence. Species of beast, age, and cut of meat were all important. At Digeon, meaty limb-joints were particularly favoured and here, unlike most shrines, wild species are well represented. At Mirebeau, abundant ritual feasting is reflected by the carpet of bones, pots and jewellery on the floor of the shrine. At Gournay (Oise) only young pigs and lambs were eaten. Here, as elsewhere, the animals chosen for ritual consumption were apparently despatched outside the holy place and certain portions of meat only brought into the sanctuary. At Gournay, only the shoulders and long-bones of lambs are present. This may be reflective of elaborate rites associated with the killing of sacred animals, involving a number of different processes. Perhaps one part of the process was a sacrifice performed in a sacred enclosure, some pieces being eaten and the uneaten portions used in other rituals which do not manifest themselves archaeologically. A second series of rites may have included the consumption of portions which had already been butchered prior to being brought into the sanctuary specifically for a feast in the sacred space.62 One interesting point about the preparation of meat for feasting is that, as seems to have been the case with graves, fire was used only sparingly; there are calcined bones, for instance, at Mirebeau (possibly the remains of a holocaust) but this is relatively uncommon.

The Celtic sanctuary at Gournay is of particular interest in terms of the different rituals represented by the animal deposits on the site. Here, the beasts whose bones were found in the shrine were treated in two entirely different ways: humans devoured the choicest portions of young, succulent pigs and lambs, while the gods seem to have been allotted tough, elderly meat that no human would have wished to eat. This apparently offhand attitude on the part of worshippers may in fact reflect instead a profound belief-system. The uneaten animals were mature horses and cattle. The horses were buried, unbutchered, in the ditch surrounding the sacred site, associated with offerings of weapons; the cattle were over 10 years old and had been used for work as traction animals before being sacrificed, left to decompose in a large pit within the sanctuary, and then reinterred in a series of ritual acts at the entrance to the shrine.63 The ditch around the holy place at Gournay received both the bones of uneaten cattle and horses and the remains of ritual feasting on pigs and lambs, but the different species occupied discrete areas of the ditch,64 perhaps because the elderly sacrificed and unconsumed beasts had a greater sanctity than the rubbish of the sacred

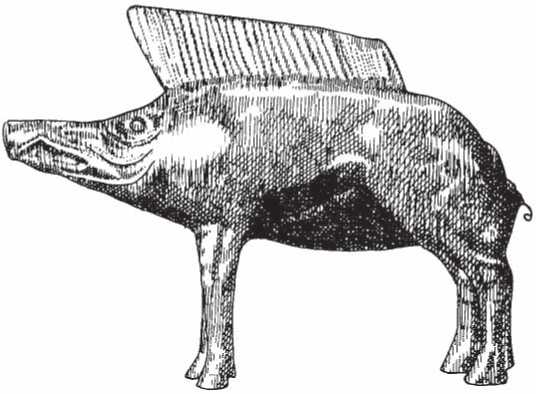

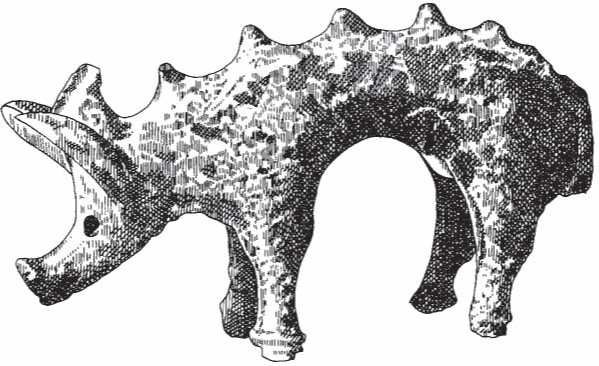

Figure 5.9 Late Iron Age bronze boar figurine, Neuvy-en-Sullias, Loiret, France. Height: 68cm. Paul Jenkins.

Banquet (which none the less had sufficient sanctity to be buried within the consecrated space). Another Gaulish sanctuary where certain animals were not eaten but offered to the gods was Ribemont (Somme), which contained an extraordinary structure or ossuary built almost entirely of human long-bones but with several horse long-bones included as well.65 In the cases where animals were offered, unconsumed, to the supernatural powers, the inference is that they were buried as gifts to the gods of fertility and the chthonic regions, who received the nourishment from the rotting carcases, just as occurred in the pits outside shrines (see pp. 100-5).

In Britain, several shrines are associated with animal burials, often in pits. This occurred, for instance, at South Cadbury (Som.), West Uley (Glos.) and Hayling Island (Hants).66 At Uley, the choice of goats and fowl (both relatively uncommon in Romano-Celtic Britain) may reflect a particular cult, that of Mercury, whose images have been found at the site67 and whose emblems were the goat or ram and the cockerel. At Cambridge, a curious sunken shrine dating to the late second or early third century AD revealed evidence of elaborate animal ritual, involving burials of a complete horse, a bull and hunting-dogs, all carefully arranged.68 Animals in shrines are discussed in more detail in the consideration of individual species which follows.

SACRIFICE AND RITUAL ANIMALS REPRESENTED IN RITUAL Dogs

Dogs played an important part in the ritual activities of sanctuaries. The sacred site of Gournay was the scene of complex ritual involving dogs during the later Iron Age. Pieces of fifteen dogs were found, consisting especially of jaw-bones, implying that there were specific rites associated with heads or skulls. Certainly the bones present seem to have been carefully selected, and there is a marked absence of trunks, ribs and vertebrae.69 At Ribemont, pieces of dog were deposited in the ditch surrounding the sanctuary.

Dogs were eaten as food in settlements, but there is only limited evidence for their consumption in shrines. However, butchery did take place at Gournay and Ribemont, which suggests that dogs were occasionally consumed as part of the ritual feasting. At Ribemont, one dog had its skull split open to extract the brain and tongue, just like the pigs found on Iron Age habitation sites.70

Dogs seem to have a particular association with sacred sites which have an aquatic connection. As early as the Bronze Age in Britain, dogs may have been sacrificed at the watery sites of Caldicot (Gwent) and Flag Fen (Cambs.).71 This water association continues through time: Ivy Chimneys, Witham (Essex), was a religious site in the Iron Age, and was associated with a sacred pond.72 The ditch contained skeletons of domestic animals and a row of dog teeth 'set as though in a necklace'. In the Romano-Celtic period, there is abundant evidence for the link between dogs and water: the Upchurch Marshes (Kent) received a

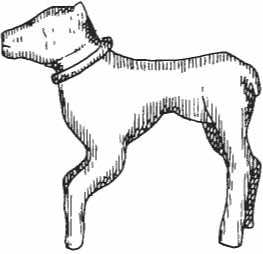

Figure 5.10 Bronze dog from the Romano-Celtic sanctuary at Estrees Saint-Denis, France. Paul Jenkins.

Deposit of seven puppies, one accompanying an adult bitch, buried in urns.73 The skulls of five dogs were deposited in a well at Caerwent (Gwent);74 at Muntham Court (Sussex), several dogs were cast into a deep well near a circular shrine; the small Romano-British site at Staines, associated with a bridge, had a well in which sixteen dogs had been deposited, presumably as a ritual act.75

The repeated association between dogs and water may suggest a chthonic aspect to dog symbolism. That these animals may have been perceived as underworld creatures is supported by other contexts in which dogs were sacrificed, namely pits and graves. The deposition of a dog in a pit (figure 5.7) is not a dissimilar practice to its placement in a deep well: the relationship with underground forces is a feature of in both contexts. Dogs were often associated with pits in Iron Age and Romano-Celtic Europe. British ritual shafts also contained dog remains, especially the skulls,76 repeating the evidence from Gournay and Caerwent. In the disused grain-storage pits of southern Britain, complete or partial bodies of dogs - with no evidence for their consumption - were interred together, sometimes with great care and within a complex context. The primary phase of occupation at Danebury, before 500 BC, when the settlement was first defended, is represented by a series of pits dug outside the line of the later defences. One of these was about 2 metres deep and in it were placed the bodies of two dogs, together with a selection of twenty other bones which represent a carefully chosen range of both wild and domestic species. After the animals had been positioned, chalk blocks were laid over the bodies and then a huge timber structure was erected over the middle of the whole deposit.77 This must reflect an elaborate ritual, perhaps to do with the appeasement of the chthonic forces on whose ground the settlement was built. Multiple pit-burials sometimes include dogs accompanied by other beasts: at Twywell, two pigs and a dog were buried together. Interestingly, there is a recurrent association between dogs and horses, arguably the closest animal companions of man. At Blewburton a horse, a dog and a man were interred in the same pit, as a synchronous ritual act.78 Horses and dogs occur together repeatedly enough for their association to be considered statistically significant at Danebury (figure 5.7), even though both dogs and horses were comparatively rare in the overall faunal assemblage.79 The link between horses and dogs seems to have been very strong: at the sunken shrine in Cambridge (p. 110), a horse and dogs were found buried together,80 and at Ivy Chimneys, dog teeth were buried in the vicinity of the body of a horse.81 Elsewhere in Britain the implied chthonic association continues to manifest itself: thus, two dogs were interred in a wooden box, together with pottery dating to the second century AD at the Elephant and Castle in South London.82 In Continental Europe, too, the link between dogs and pits is demonstrated by the entire skeletons deposited in deep shafts at such locations as Saint

Bernard, Bordeaux and Saintes in Aquitaine, and at Allonnes in the north of France. Dogs played a prominent role, too, in the ritual activities centred on the pits at Bliesbruck (Moselle), in which many parts of dogs were deposited.83

Celtic graves bear ample evidence of dog ritual: sometimes there is an indication that the animals were food-offerings, sometimes that they were sacrificed uneaten, in different ceremonies. In general, dogs appear far more frequently in the cemeteries of the later Iron Age. A dog formed part of a rather grisly ceremony at Tartigny (Oise): he was probably sacrificed at the death of his master. The man was interred with a hare, the jaw of a horse, and a young dog whose bones bore traces of cutting: the animal had apparently been skinned, and there were marks on the bones around the stomach which are indicative of the creature's evisceration;84 whether dead or alive when he was subjected to this brutal ritual is not known. Other evidence of dogs accompanying humans to the afterlife occurs at the Iron Age cemetery of Acy 'La Croisette', in Champagne, where three small dogs were interred with their master.85 But at Epiais-Rhus, dogs were food-offerings and pieces of dog, including isolated legs, represented gifts of meat for the journey of the deceased or a fee for his passage to the next world. The same cemetery produced evidence that some dogs were burnt, maybe sacrificed to the gods of death.86

Horses

In the sixth century BC, a cave at Byciskala, at the eastern edge of Celtic Europe, in Czechoslovakia, was the focus of an elaborate ritual which involved the interment of forty women, possibly the result of human sacrifice, and the ritual killing of two horses which had been quartered, together with other offerings of humans, animals and grain. In a cauldron was a human skull, and another skull had been fashioned into a drinking-cup.87

Two Gaulish sanctuaries, Gournay-sur-Aronde (Oise) and Ribemontsur-Ancre (Somme), display very distinctive rituals associated with horses, whose bones were used for religious purposes. At Gournay, seven mature horses were buried in the surrounding ditch.88 The skeletons had been exposed and allowed to decompose sufficiently for manipulation of the bones to be possible; then the remains were regrouped in discrete anatomical collections and buried in isolated parts of the ditch. The fact that the horses were deposited in association with numerous weapons (many of which had been ritually bent or broken) may reflect a rite related to war (see chapter 4). We may recall the vow of the Cimbri at the Battle of Orange in 105 BC to dedicate all the spoil, sacrificed enemies, horses and weapons to the gods.89 The evidence of

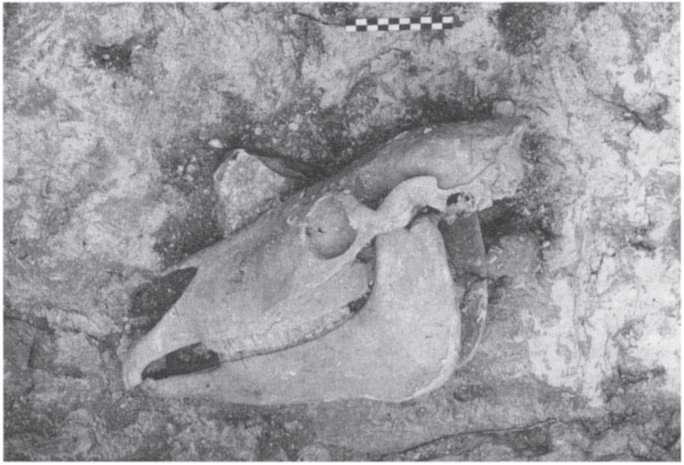

Figure 5.11 Horse skull placed as a ritual deposit in a disused Iron Age grain-storage pit, Danebury, Hampshire. By courtesy of the Danebury Trust.

Very curious ritual behaviour can be seen at Ribemont, where a kind of bone-house was constructed: this consisted of a structure built from human limbs and those of horses, which had been carefully selected so as to be the correct length for symmetry and stability. The horses had been allowed to decompose to liberate the long-bones. There were more than 2000 human long-bones in this 'ossuary', placed crisscross, to form a square, open on one side, and with a central post. The whole construction was encircled by weapons and shield-bosses. The horse bones came from about thirty adult animals, mostly over 4 years old. There were no signs that butchery had taken place. Indeed, the humans and horses who formed the construction seem to have been treated without differentiation.90 But in some sanctuaries, horses were apparently eaten in ritual feasts, as indeed were dogs, as we have seen.

Ritual in holy places associated with sacrificed or dedicated horses manifests itself all over the Celtic world: in the late Iron Age oppidum of Liptovska Mara (Czechoslovakia) a cult area was centred round a large pit containing the remains of burnt animals including horses and dogs.91 At the other side of the Celtic world, one of the 'shrines' at the great hillfort of South Cadbury (Som.) was associated with pits containing horse and cattle skulls which had been carefully buried the right way up.92 In Romano-Celtic Britain, horses were buried under the threshold of a third-century

AD basilical shrine, at Bourton Grounds (Bucks.), perhaps as foundation-offerings.

Horses played a part in sepulchral ritual: two Iron Age vehicle-burials at Soissons (figure 5.8) were accompanied by horses, bulls, goats, sheep, pigs and dogs, all interred complete.93 In Britain, the corpse in the chariot-burial at the King's Barrow in north-east England was interred not only with his dismantled chariot but his horse team as well,94 although the animals were generally represented symbolically by bridle-bits or other harness. If the dead had been warriors, then the deliberate loss of valuable war-horses must reflect the very high status of their owners. But sometimes a single bone of a horse was placed in a grave as a symbolic, token presence: thus one horse tooth was included in the assemblage at Rouliers in the Ardennes, and at Epiais-Rhus;95 and similarly at Tartigny, we have seen that a mandible alone represented an 8-year-old horse.96 The two Ardennes cemeteries of Mont Trote and Rouliers each contained horses; these were young animals which had just achieved maturity,97 in contrast to the much older animal represented at Tartigny.

Ritual pits, especially in Britain, demonstrate the importance of horses in sacrificial ritual, though there are Continental parallels, as in the pits at Saintes which contained the complete bodies of horses.98 In the British pits, as is the case with dogs, particular attention was paid to the head (figure 5.11): skulls of horses were found ritually placed in pits at Newstead in southern Scotland.99 The horses buried in the storage pits of southern England show no evidence that they were butchered, although horses were eaten on settlement sites. It is important to recognize that horses are overrepresented as 'special deposits' in storage pits, compared to the general animal populations on the sites containing these pits. Horses were buried either alone as entire carcases, as partial skeletons, or as part of multiple animal deposits. A horse was interred in a pit at Tollard Royal (Wilts.);100 and a horse, a dog and man together at Blewburton.101 Dogs and horses appear together at Danebury again and again, an occurrence which must reflect a specific cult-practice, perhaps associated with hunting.102 The skulls of horses at Danebury, which form the main evidence for horses here, were often deliberately placed at the very edge of the pit bottom, under the overhang of the lip, which is the same position as human bodies and skulls occupy. Horse-gear is also present as pit-offerings,103 perhaps symbolically representative of the horse itself.

The horse ritual at Danebury is varied and interesting: in one pit, where a horse and a dog were interred together, one front and one hind leg of the horse were removed from their proper positions and the head of the horse was placed behind the torso, next to the dog. In another Danebury pit, the articulated head, neck and chest of a horse were placed in the hole after it had been partially filled with rubbish. The pelvis and sacrum were carefully and deliberately positioned over the vertebrae; the rest of the skeleton is missing. Two large nodules of flint were carefully placed inside the chest cavity, and Annie Grant suggests that the horse may have been cut open and eviscerated before its interment. The complete carcase of a young pig was placed against the horse, and a second one on the other side of the pit. In the same layer within the pit were burnt flints, chalk blocks, slingstones, sherds of pottery and a broken whetstone, which had been placed against the jaw of the horse.104 This must reflect a complex ritual which we can have no means of reconstructing from the evidence at our disposal. All that can be said is that the horse seems to have been the centre of the cult practice represented by this particular pit.

Grant105 argues that it could have been because horses did not contribute greatly to the economic base of such sites as Danebury that they were deliberately chosen for sacrificial ritual. Horses are expensive to feed and their most important quality is their speed, though they could be used as light draught animals. They were not a major food source. Her contention, therefore, is that surplus horses were available for sacrifice and that this may be why horses, like dogs, are overrepresented in cult contexts. But there are some problems with this argument. Elsewhere, Grant suggests that horses were not actually bred at Danebury but were probably rounded up from feral herds when required. If this were so, then there would be less likelihood of there being surplus animals around because only the ones that were needed would have had to be kept and fed as domestic beasts. The other problem is a religious one. If the whole idea of sacrifice is that it does represent a genuine secular loss to a community, is it not unduly cynical to introduce an argument based upon expediency as an answer to the problem of overrepresentation of horses in pits?

Pigs

Pork was an important source of food for the Celts (chapter 2) and, because of this, there is abundant evidence for the sacrifice of pigs to the gods. Pig rituals fall into two groups: the first where the animal was slaughtered but not eaten and was buried as a gift to the supernatural powers; the second where pigs were butchered and the pork either was placed as a food-offering to the dead or was consumed in a ritual feast.

Both types of pig remains occur in Celtic graves. In Gaulish cemeteries there is considerable evidence that pigs were favoured above other meat. There are also indications that certain cuts of pork were chosen for particular graves or cemeteries. Most distinctive of all is that in very many sepulchral contexts, age was an important factor and that the

Figure 5.12 Late Iron Age bronze boar or pig figurine, Hounslow, Middlesex.

Paul Jenkins.

Choice was for young animals, between birth and 2 years old. So in many instances, the optimum time to slaughter for meat (at the achievement of maturity) was ignored and a deliberate choice was made to kill the sacrificial pigs before this time.

The Iron Age cemetery of Tartigny contained five graves, each with a different selection of animal deposits. Pigs were the most frequent here, and definite evidence for food preparation and feasting was present: often the carcases had been split in two. There was evidence of a systematic method of ritual deposition: legs were without their extremities; spinal columns were most common; and the heads had been split to extract brain and tongue. Each grave possessed different deposits: in one there were only fragments of vertebra; in another, a 7-month-old piglet had been skinned and split in two; in a third grave, twelve fragments of spinal columns belonging to five individuals had been buried, together with part of a sow.106

In the cemeteries of the Ardennes region, pigs were a central feature of the funerary ritual, both as offerings to the dead and the gods and as part of the funerary banquet. The meat-offerings to the dead at Acy-Romance were once again from young animals. The same age preference was observed at Rouliers and Mont Trote. Here there were many juveniles but, interestingly, no boars. Both these cemeteries showed evidence of a curious rite, in which pigs were buried each with only one foot attached. At Rouliers, there is a suggestion that pigs accompanied the male burials, sheep the females.107

Other Gaulish cemeteries displayed similar emphasis on pig ritual: changes through time, between the third century BC and the Romano-Celtic period, are discernible at Epiais-Rhus, and pork seems to have supplanted other meat as ritual offerings in later periods. Sometimes pigs are represented by just one bone, reflecting the offering of a single joint of pork to the dead: but heads, ribs and vertebrae were split to extract nourishment and are evocative of meals taken at the grave side. Filleting and food preparation took place at the cemetery of Allonville (Somme), where mandibles and bits of split skull were buried after a ritual banquet.108

Uneaten joints, offerings to the dead or to the gods, could be represented in graves either as single, modest pieces of meat or as partial, articulated skeletons, the latter indicating that the portions were deposited relatively fresh.109 Joints of pork were placed near the heads of corpses in graves of people buried in Dorset in the late Iron Age,110 as if in readiness for consumption by the deceased. Many chariot-burials, both in the Marne area of eastern France, like La Gorge Meillet, or in Britain, as at Garton Slack, contained pork joints.111 One Yorkshire woman was buried clasping part of a pig in her arms. But the cart-burials at Soissons contained entire pigs, horses and other domestic animals who, uneaten, accompanied their lord to the Otherworld, to continue their service to him there.

Apart from graves, there is substantial evidence that pigs were sacrificed, sometimes consumed in ritual feasts where the spirits and humans were linked in convivial ceremonies. Pork was the favourite meat in most Gaulish sanctuaries: again, as with graves, the preference was for the young animal. Thus at Gournay112 young pigs and lambs were butchered, cooked and devoured; at Mirebeau pigs and cattle were killed young; and at Ribemont at the beginning of maturity (at about 2 years old or slightly younger). At this shrine, the males were slaughtered at an earlier age than the sows, who were mostly 3 or more years of age at death. Choice of cut was equally significant in the sanctuaries: at Ribemont, people preferred the meat of the spine, chest and head; at Digeon the succulent upper limb portions were selected.113

British sanctuaries show some evidence for pig sacrifice: the late Iron Age shrine at Hayling Island (Hants) yielded large quantities of pig and sheep bones in the faunal assemblage.114 One of the alleged late Iron Age shrines at South Cadbury (Som.) is associated with an avenue of burials of young pigs, calves and lambs.115 The Romano-Celtic temple at Hockwold (Norfolk) had been built with the four columns of the cella (inner sanctum) resting in pits each containing pig and bird bones.116 The inference is that these animal remains formed part of a foundation ritual, in which appeasement-offerings were made to the local gods where the shrine was built. The burial of a young boar at Chelmsford may similarly have been a foundation-offering.117

Pigs form a significant proportion of the animals buried as deposits in Celtic pits. The offerings at Argentomagus consisted mainly of pig; and a complete young pig was interred in a pit at Chartres.118 'Special deposits' in British pits also contain pigs, which may be partial, complete or multiple. The body of a pig deliberately covered with lumps of chalk was found at Chinnor (Oxon.).119 Two pigs and a dog come from a pit at Twywell (Northants); at Winklebury (Hants) a pig and a raven were interred together; at Danebury, a pig and two calves were together in one pit, while in another were deposited two pigs and a horse.120 At Danebury, pigs seem to have been especially important during the middle period of occupation (400200 BC), whilst elsewhere121 pig bones are particularly common in pits belonging to the Roman period.

Why were pigs so important in sacrificial ritual? One answer is that these animals were a favourite source of food for the Celts: thus it would be a genuine act of propitiation to share with the gods something valued in economic terms. Secondly, there may have been some fertility symbolism specifically associated with pigs. Farrowing sows produce large litters, which perhaps gave rise to imagery of general fecundity and prosperity. Pigs certainly are linked with fertility in some cultures: among some Nuba peoples of the Sudan122 the bones of pigs protect granaries, and it is considered wise to keep the skulls of slaughtered pigs in the belief that this will ensure a continuing supply of these animals. In a Tosari burial at Jebel Kawerma, a human body was interred wrapped in a pigskin. This may have been a regenerative rite, to ensure the rebirth of the dead individual in the spirit world.

Cattle

Herds of cattle were a measure of wealth and a symbol of prosperity in Celtic society, and were crucial to the Celtic economy for food, draught, milk and leather. Like pigs, cattle played an important role in pits, graves and sanctuaries, as food-offerings, as a component in the ritual feast, or as uneaten offerings to the gods. Indeed, long before the Celtic period in Britain, as early as the Neolithic and Bronze Ages, the occurrence of cattle as deposits in major symbolic monuments suggests that they were of great importance in prehistoric ritual.123

One of the most important cult sites, in terms of its cattle ritual, was the sanctuary of Gournay-sur-Aronde, where a number of elderly cattle - mainly male and with a high proportion of bulls - were sacrificed. Age and masculinity seem to have been important. The animals present are not representative of a normal population. They were mostly more than 7 years old when sacrificed and thirteen were veterans of more than 12 years. The cattle had not been specially bred for sacrifice but had been used as draught animals first of all. The beasts were probably led into

Figure 5.13 First-century BC/first-century AD iron firedog, with terminals in the form of bulls' or horses' heads, Capel Garmon, Gwynedd. By courtesy of the National Museum of Wales.

The sanctified area and were despatched in front of a series of sacred pits: of these nine were grouped in sets of three and surrounded a larger oval pit. Each animal was led to the pit and then killed according to a precise ritual formula, in which a sharp blow was given by an axe to the nape of the neck, causing instant death. Since the head would need to be lowered in order to deliver such a blow, the animal had probably been offered food and was eating at the time of its death. There may have been an element of the animal's somehow seeming to consent to its death, by its acceptance of food. This form of killing was the result of particular choice: the more normal method of slaughter would be by cutting the animal's throat. The carcase of the ox or bull was then dragged into the great central grave-pit and allowed to decompose for about six months. In the surrounding pits, weapons were temporarily interred. Once the corpse was sufficiently rotted for the joints to be parted, the carcase was pulled out of the pit and the empty hole cleaned: tiny tell-tale bones have been found, attesting to the former presence of the cattle in this grave-pit. The main part of each animal (especially the head, neck, shoulders, spine and pelvis) remained within the sanctuary, while the rest of the body was taken away, perhaps for some other ritual purpose. What happened next to the carcases within the sanctuary formed a complicated and fascinating series of religious acts. The skulls were separated from the rest of the bodies: at some time after death the lower jaws were removed and the heads given a sword-thrust to slice off the muzzle. These skulls were re-exposed and stored, whilst the pelvis, neck, shoulder and spine of the cattle were carefully deposited in ordered heaps on either side of the sanctuary entrance. Successive acts each consisted of the placement of the bones of about ten animals. This behaviour was repeated at regular intervals of about ten years. The skulls were added after each deposition and were placed between each main layer. About 3,000 bones flanked the entrance, and there was sometimes synchronization of deposition, pairs of animals placed one on each side. In addition, more than 2,000 weapons from the nine interior pits were placed in the ditches with the bones, suggested as being consistent with the repeated dismantling of trophies which were previously displayed on the palisade or portico.124

Brunaux interprets the treatment of the cattle at Gournay as being associated with a chthonic ritual, in which the animals rotted and 'fed' the earth into which the decomposing flesh and blood soaked. The ten central pits were dug in the mid-third century BC, but in the late third or early second century the nine grouped pits served as foundations for the first temple, a building whose primary purpose was to protect the great oval decomposition-pit in which the animals rotted. This decomposition process may have been the most important of the rituals which took place at Gournay. The cattle may have been especially selected, perhaps because of appearance, temperament or even longevity. Their age and their use as working animals could mean that they were spoils of war, a factor which would have contributed greatly to their cult status. The piling up of cattle and weapons beside the sanctuary entrance was a religious act designed to guard the most vulnerable part of the temple boundary, where sacred and profane space was not physically delimited.

Other Gaulish and British sanctuaries show evidence of ritual involving cattle: at Digeon (Somme) oxen formed important offerings: and at Mirebeau (Cote d'Or), young cattle (between 2 and 4 years old) were killed and eaten in cult banquets. Interestingly, the selection of parts of animals for burial at Gournay - namely heads, spines, pelvises - contrasts with that at Ribemont (Somme), where cattle are represented above all by their ribcages.125 In Britain, several shrines show signs of cattle sacrifice and ritual: outside a rectangular shrine at South Cadbury Castle, an adult cow was buried; another small sanctuary at the site was associated with six pits containing horse and cattle skulls. A third sacred building was approached by an avenue of pit-burials of young animals, including calves.126 An Iron Age structure at Uley (Glos.), a possible precursor of the later Roman shrine, is associated with the deposit of iron spears and the articulated limb of a cow.127 Ox or cow burials were present at a number of Romano-British sanctuaries, notably at Brigstock (Northants), Caerwent (Gwent), Muntham Court (Sussex) and Verulamium (Herts.). A complete bull was interred along with other beasts at the subterranean Cambridge shrine.128

Celtic graves have yielded evidence of cattle, either as food for the dead, offerings to the gods or meat for the funeral feast, though they were not as popular as either pig or sheep. We have to be careful in making such assumptions from the faunal evidence, however, since a cow or ox will, of course, yield much greater supplies of meat than either a pig or a sheep. Young animals accompanied burials in the early La Tene cemetery of Acy-Romance (Ardennes). Young cattle were again present at Mont Trote and Rouliers in the same region.129 Sometimes entire animals were sacrificed when a person died: this happened, for instance at Soissons, a cart-burial accompanied by a cortege of animals including bulls; and another vehicle-burial at Chalon-sur-Marne included oxen.130 By contrast, a single bone might be symbolically placed in a tomb as a token of a whole carcase, as at Rouliers. In the cemeteries of Champagne, cattle were more popular in the earlier Iron Age than in later periods. Here, a deliberate selection of portions was made, favouring the meaty limbs, thighs and shoulders.131

British burials, too, included cattle as grave-goods: the animal remains at the early Romano-British cemetery of Skeleton Green included cattle, the males seemingly deliberately chosen to accompany male humans.132 In Dorset, late Iron Age bodies were buried with a joint of beef by the head, presumably as a food-offering for the dead or the gods of the underworld.133

Ritual pits, too, bear evidence of cattle-sacrifice and interment and here it was upon the skulls that the ritual appears to have been focused. Cattle are one of the main species represented in the corn-storage pits of southern England.134 They appear at Danebury, particularly in the earlier phases, pre-400 BC.135 Ritual pit-deposits of cattle occur widely in Celtic Europe: thus they were the species particularly favoured in the pits of the sacred site at Bliesbruck, where they are present usually as articulated bones, especially the vertebrae.136 The mid - to late first-century BC cult site of Liptovska Mara in eastern Europe was centred on a large pit containing burnt animals, including cattle.137

It is clear that since cattle were so crucial to the rural Celtic economy - not simply for meat but for so many other products and for draught - they formed a significant component in sacrifice, gifts to the supernatural powers of commodities of great value to a community. We can have little perception of the precise rituals involved or of the belief-systems

Figure 5.14 Bronze brooch in the form of a ram, fifth century BC, Aignay-le-Duc, Cote d'Or, France. Length: 3.7cm. Paul Jenkins.

Surrounding them. Classical writers are very silent on details of animal sacrifice, but we do have Pliny's comment138 on Druidical sacrifice of two white bulls, on the occasion of the sacred rite of mistletoe-cutting, where the parasitic growth was severed from the holy oak with a 'golden' sickle and caught in a white cloak. The colours required for both animals and cloak may have been associated with the milky appearance of the mistletoe berries. Mistletoe, with its winter growth on an apparently dead host and the resemblance of its fruit to drops of milk, was a powerful symbolic promoter of fertility when prepared as a drink within a religious context. It may well be that the two bulls were sacrificed, like those at Gournay, to the chthonic gods, to replenish the fecundity of the earth.

Sheep

Less common than pigs, sheep none the less feature in the meat-offerings and ritual banquets of Celtic shrines and graves. Sheep seem to have been treated similarly to pigs, in that again the preference was for young beasts. Lambs of 3 or 4 months old were favoured at Gournay, but only the shoulder and leg portions were brought into the sanctuary and consumed. At Mirebeau, sheep were slaughtered at 2 years old, as they attained adulthood: this would be the optimum time for killing, in that the animal was at maximum size but young enough for its meat to be tender, so here, the succulence of the meat was a prime consideration.139 Species preference sometimes manifests itself in sacred places: lambs for consumption were preferred above all at Gournay, whilst the preference was for pigs at Ribemont. At Hayling Island, both pig and sheep are especially well represented in the faunal assemblage of the late Iron Age shrine.140

The animal remains in graves often exhibit a predilection for both pork and lamb. In the Ardennes cemeteries of Rouliers and Mont Trote, both

Species played an important role as food-offerings: at Rouliers, the sheep seem particularly to have been associated with female tombs, pigs with the male burials. Once again, there was a preference, in sepulchral contexts, for young animals: the dead liked their meat tender. There is evidence for the lesser status of sheep over pigs in Gaulish graves, for instance, at Tartigny141 and at Allonville, where in one tomb one sheep is accompanied by six pigs.142

Both British and Continental pits contained sheep as votive offerings to the underground or chthonic forces: at Allonnes, whole sheep were buried in ritual pits.143 Skulls of sheep were cast into British wells in both the Iron Age and Romano-Celtic periods.144 As 'special deposits' in corn storage pits, sheep are generally underrepresented compared to the general population. At Danebury, sheep were the main domestic species in the economy of the community, but relatively few have been found in the context of ritual pits at the site. A complete sheepskin with its lower limbs still attached, found in one Danebury pit, represents a considerable economic sacrifice to the owner. In one of the multiple animal burials at Danebury, two sheep and a domestic cat were interred together.145 The scarcity of sheep in cult deposits at Danebury could mean one of several things: either sheep were economically too valuable to be 'wasted' in a sacrifice; or, because in secular life sheep were only eaten after they had been fully utilized for wool and milk (see chapter 2), the ritual reflected everyday life; or it may be that mutton was not particularly liked at all.

As far as the evidence allows us to judge, sheep were of secondary significance as cult-offerings compared to their crucial importance in the economy. They are consistently present in sanctuaries, tombs and other ritual contexts, but in terms of real numbers they take second place to pigs and sometimes to cattle as well. The reason for this may be a religious one or it may derive from economic considerations such as were suggested above in respect of Danebury.

Other animals

Bones of wild and domestic animals of species other than those already discussed turn up only sporadically in ritual contexts. Goats do not appear to have been common, although there is a problem here, in that it is often impossible to distinguish goats from sheep in faunal assemblages. But goats were buried entire as part of the funeral cortege at Soissons;146 and there is some evidence for ritual goat-burials at Danebury (figure 5.2). Goats were prominent in the cult deposits at Uley, where they may have been associated with the cult of Mercury. More rare still are cats: again they appear at Danebury, in company with two sheep.147 Two young wildcats were buried in a ritual pit at Bliesbruck (Moselle), victims of an infection which evidently resulted in tooth loss and therefore starvation.148

Deer, bear, fox and hare are among the wild animals which were occasionally sacrificed and their bodies used for ritual purposes. The creatures of the wild were rarely eaten (see chapter 3). Two teeth of a young bear were buried in the Celtic cemetery of Mont Trote: the youth of the creature reflects the general preference at the site.149 A young hare was buried entire, together with a young dog, in the tomb of a man, perhaps a hunter, at Tartigny.150 The great ritual enclosure at Aulnay-aux-Planches (Marne) may have been used from the tenth to the sixth centuries BC. Here were sacrificed a dog, a fox and a young bear.151 Fox and deer are relatively common among the wild creatures represented in ritual contexts, and on occasions they were apparently despatched together: thus at Winklebury, a red deer and twelve foxes were interred in an Iron Age pit deposit.152 Deer and fox were prominent in the ritual assemblage of the Digeon (Somme) shrine, a sanctuary distinctive in its bias towards wild species.153 Deer are perhaps the most common wild and hunted creature represented in British ritual pits.154 At Ashill (Norfolk) boar tusks and antlers were buried in a well with more than a hundred pots;155 and a pit at Wasperton in Warwickshire contained two sets of antlers arranged to form a square enclosing a hearth.156

Perhaps oddest of all creatures to be found in ritual contexts are frogs and toads: a chariot-burial at Chalon-sur-Marne contained a hundred frogs placed in a pot;157 and a ritual pit in Aquitaine158 contained toad bones. The amphibious nature of these beasts may have endowed them with a special symbolism associated with life and death.

Birds

The ability to fly endowed birds with great symbolic meaning for the Celts (see chapters 7, 8). It may have been, at least in part, for this reason that bird bones appear in ritual contexts. Birds may have been perceived as spirits or perhaps the souls of the dead. Among the Borneo tribe of the Iban, birds are regarded as a link between the living and the ancestral spirits, since they share the celestial domain of the spirits.159

Apart from a general symbolism, different birds played differing roles in sacrifice and ritual. In late Iron Age and Romano-Celtic contexts, domestic fowl and geese were present. Interestingly, Caesar comments160 that neither geese nor chickens were eaten by the Britons, but both certainly appear as food-offerings in Gaulish graves161 and indeed chickens do occur in late Iron Age domestic refuse on British sites.162 Chicken

World History

World History