A burial contains numerous, individual microenvironments, each of which has a different preservation potential, which in turn can provide evidence of human diets. Animal and plant food residues can be recovered from the lower intestinal tract, oral cavity, associated vessels, other forms of burial offerings, and fragments or whole plants or animals deposited in the burial. Individual microenvironments at a burial site result from many aspects including, but not limited to: (1) preparation of the burial feature, (2) addition of burial offerings, (3) depth and orientation of the corpse, (4) edaphic conditions such as moisture and pH, (5) microbial activity, and (6) exposure of the burial when it is excavated.

When burials are discovered at sites, the subsequent excavation and removal process should be done with caution and should take into consideration the subsequent types of laboratory analyses (see Burials: Excavation and Recording Techniques). Failures during the recovery phase, or the use of improper sampling strategies, will compromise the ability to provide valid interpretations. In addition, burial sampling must include control samples from the burial fill and surrounding contexts.

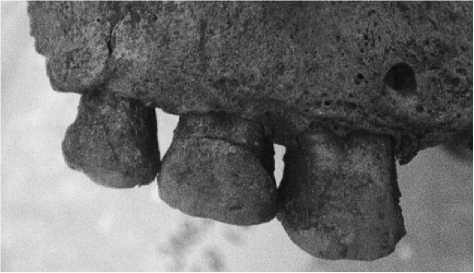

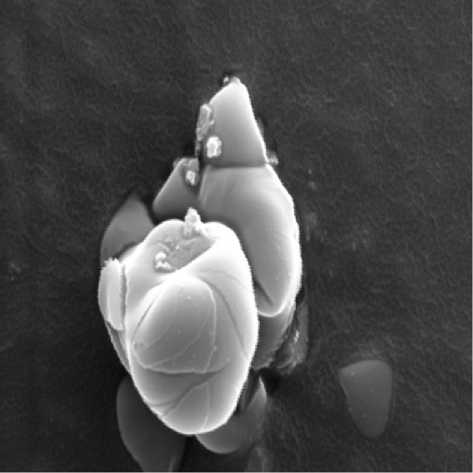

When found, a skeleton or mummified burial normally has two areas where dietary residues can be easily recovered. In life, dietary residues (i. e., pollen grains, phytoliths, starch granules, plant fibers, animal hairs, etc.) are produced or released during mastication and some of these can become trapped in dental plaque (see Pollen Analysis). If not removed, within a few days, plaque is mineralized and adheres to the teeth in the form of dental calculus. Large deposits of calculus are often found on teeth (Figure 1). Dietary microfossils and residues that were trapped in the calculus are easily recovered during laboratory analysis (Figure 2). Sometimes artifacts or vegetal materials are placed in the mouth of the deceased, especially in the Andean region of South America. Such types of vegetal materials can often be recovered and identified as microfossils or macrofossils present in the area of the oral cavity of a burial.

The second burial area of dietary interest is the abdominal area, specifically the sacrum and the soil inside the pelvic girdle. In some well-preserved burials, distinct fecal pellets (coprolites) can be found in the abdominal area because the colon is located in that area. However, for most burials, distinct coprolites are not visible, but controlled sampling of sediments in the pelvic girdle area may reveal seeds, starch grains, phytoliths, pollen, and other types of residues of dietary and medicinal importance.

Figure 1 Photograph of dental calculus. Microfossils from dental calculus reflect diet for a few days prior to death.

Figure 2 Microfossils, for example the starch grains illustrated here, are quite common in dental calculus.

In some types of burials, a variety of grave offerings are included with the body. If present, each bowl or other type of vessel in a burial becomes its own microenvironment, which can offer evidence of its original contents (i. e., pollen, starch, phytoliths, and macrofossils). Some types of grave offerings present better microenvironments of preservation. For example, basketry vessels are less durable than ceramic vessels, and therefore have less preservation potential. Objects made of copper or copper alloy promote preservation because the copper oxide produced by the object is toxic to most types of microbial decomposer organisms.

When containers are found in burials, there are various techniques that should be used to sample for dietary residues. For ceramic vessels, a rinsing of the inside, bottom portion is appropriate. Ideally, burial artifacts should be collected in the field, placed in Sterile containers that are then sealed, and then sent to a laboratory where the contents can be removed in a controlled environment. A control sample of burial sediment around the exterior of each vessel should be collected, examined, and then used as a basis for comparison with the contents recovered inside the vessel. In burials where recovered ceramic vessels are cracked, it is often appropriate to remove the sediments in the vessel in the field. In cases where burial vessels are fragmented, analysis of the shard will sometimes provide useful palaeoethnobotanical data.

The importance of collecting control samples of the burial fill and from areas above and below the burial cannot be overemphasized. Any interpretations of Paleoethnobotanical data recovered from burials (i. e., mummy or skeleton, vessels, artifacts, burial floor surface) are dependent upon comparisons to data recovered from site and burial control samples. Extensive analysis of the contents of control samples will allow analysts to distinguish which items are probable evidence of diet or medicinal use and which items might instead reflect site contaminants.

World History

World History