Origins and Current Debate

Although the methodology of stratigraphic analysis is hotly contested among archaeologists today, the procedures are among the oldest developed in scientific archaeology. By the end of the eighteenth century, stratigraphic methods were gradually being applied to the understanding of both archaeological and geological deposits, and thus Thomas Jefferson’s pioneer efforts at stratigraphic excavation in 1794 antedated Christian Thomsen’s typologically based ‘three-age system’, introduced with the opening of Copenhagen National Museum (1819).

Yet, ever since the development of typological methods, archaeological theory has largely centered on typology and typologically oriented issues, whereas stratigraphic theory and debates have remained more or less subsidiary issues, and thus lag far behind the discussions based on typological analysis (e. g., world systems, diffusionism, style, ethnicity, etc., aside from art historical approaches). The result is that where stratigraphy comes to the forefront, the internal theoretical debate involves several fundamental differences (concerning the importance and character of excavation units and layers and the correct terminology) which are completely unrelated to the public interpretive debate over chronological and historical questions.

The Case of Tell el-Dab’a

Before moving on to a survey of forms of stratigraphic thought, to illustrate the disparities between the various types of discussion today, we will use a relatively prominent and highly contested site, that of Tell el-Dab’a in the Egyptian Nile Delta. Excavated by an Austrian mission under the direction of Professor Dr. M. Bietak, the site provides unusually good stratigraphic sequences with artifacts in layers and in tombs, as well as monuments, which can be linked to the Aegean, Syria, Palestine, and Egypt. As the materials themselves can be linked to both chronology and historical developments in the entire eastern Mediterranean, the site has attracted considerable interest from both Aegean and biblical archaeologists, as well as from Near Eastern and Egyptian archaeologists. Inevitably, most of the public debate has centered on the issue of the chronological position of various features, such as parallels for fragments of Aegean-like paintings and actual Palestinian type axes and pottery unearthed in the excavations.

The excavations thus offer an intricate web of interrelated issues, and all of these questions involve stratigraphic aspects, since the chronological attributions of the monuments and the artifacts depend upon their stratigraphic context. In fact, however, the entire argument has taken place in the absence of a publication of the stratigraphic evidence, as a stratigraphic survey remained unpublished more than two decades after the chronological debate began to get quite warm.

Instead of sections, the excavators have published sequences of artifacts (some derived from tombs); instead of an independent stratigraphic nomenclature for each excavation and excavation trench, the excavators published material in terms of overarching stratigraphic sequences (in an alphanumerical soup of almost unfathomable complexity) which are ultimately chronological rather than depositional or architectural or typological in character. In one of the few published sections, one can note that the term for the ‘layer’ or ‘level’ ‘E’ combines floors and debris from collapse and apparently depositions from different periods. Thus the rapid survey of a couple of meters of a single section (one of hundreds of meters of unpublished sections, representing hectares of excavated area) reveals that this unit is neither a stratigraphic unit (neither in the sense of a depositional ‘layer’, nor an interpretive unit such as a ‘level’) nor a chronological unit (in the sense of a discrete uniform unit). In fact, therefore, the common point in this section is a wall, and the common point for the overall excavation strategy is that E = Hyksos period. It is thus a typologically and defined chronological unit used for a historical period, and does not have a specifically coherent architectural, typological, or stratigraphic character.

Significantly, virtually none of the debate about Tell el-Dab’a discusses the premises of the stratigraphic excavation nor the methodology, but rather centers on shifting the various pseudo-layers up and down on a chronological scale, depending upon typological and historical considerations. From a methodological viewpoint, this is effectively inadmissible because any stratigraphic argument must depend upon the stratigraphy and not upon the typology or the interpretations of historical developments. The public debate is usually about the chronological alignments whereas the criticism here concerns the failure to incorporate a deposit-oriented approach. Thus, four different issues are in fact confounded: typology, architecture, chronology, and deposits. However, the key point is the fact that although the chronological debate is invariably referred to as ‘stratigraphic’, the stratigraphic underpinnings of the argument do not usually enter the discussion.

Philosophical Origins

In principle, therefore, it must be recognized that both the methodology and interpretation of excavations are ultimately dependent upon stratigraphy. Unfortunately, it must be admitted that the case of Tell el-Dab’a is far from exceptional: most archaeological debate about stratigraphy consists of what are effectively chronological, historical, and typological discussions. It is even more regrettable that many of the discussions concerning the theoretical debate about stratigraphy are dominated by debates on terminology rather than methodology. To understand the difficulties which have led to this confusion about the use of stratigraphy, we must turn back to the various interpretations of stratigraphy. In principle, the earliest approaches to stratigraphy can be recognized in two different traditions.

One is that used in the Palaeolithic excavations of France where layers are viewed geologically, and distinguished both in terms of (1) actual composition and sequence and (2) the typologically classified artifacts enclosed in those layers. Thus, the analysis of the composition of the layers and the faunal remains can reveal climatic changes and the analysis of the artifacts in the layers provides chronological indicators. Layers or sites are thus classified in terms of the glaciations (e. g., Wurm or Riss) and in terms of chronologically recognizable artifact categories (e. g., Perigordian or Gravettian). This method can be traced back to the earliest excavations in Europe, and represents the strongest tradition in the understanding of archaeological stratigraphy.

However, this approach suffers from the major difficulty that most archaeological excavations are historical, and the composition of the layers is not only pedological (rather than geological), but also occasionally strongly influenced by human activity, including, for example, architecture. Therefore, the other mainstream approach, classifying according to architectural levels, is more recent and equally common today, being largely a development from the late nineteenth century and Schliemann’s excavations at Hissarlik which he identified as Troy. The same model has been applied to numerous other sites, including, for example, Koldewey’s excavations at Babylon and Woolley’s at Alalakh. At such sites, the sequence of levels is based on construction phases, and each phase is identified in terms of either historical (e. g., Hellenistic, Homeric, Hammurabi) or typological (e. g., Early Bronze, Late Bronze) criteria, which are in turn assigned a chronological position, based primarily on the typology. The layers and the architecture are intimately linked.

These two approaches represent the two important philosophical approaches to stratigraphy, and the greatest challenge facing archaeologists is trying to link approaches involving stratigraphic deposits and architecture, and most of the theoretical debate about stratigraphic analysis today involves these issues. It should be noted that such a discussion is methodological and effectively a completely different discussion than the debates surrounding the interpretation of the ‘layers’ at Tell el-Dab’a.

Current Understanding

Today, the study of stratigraphy is a complex and highly contested field, with differences ranging from a highly geological approach to a highly architectural approach. In practice, there is a great divide between the theoretical tools and the realities of excavation strategies. It should be evident that every single archaeological excavation is unique in material, goals, and strategies (as well as funding and time), and thus any theoretical framework must be adapted to the practical project. Furthermore, regardless of intellectual spirit, every excavator is influenced by that individual’s specific educational environment - and the methodologies used by individual excavators will change as they gain experience. The result is that not only are there numerous variations of the theoretical approaches, but there are also myriads of specific approaches visible in publications - and the published versions differ distinctly from the methods used in the field, which are constantly changing.

Therefore we simplify. In principle, despite many differences of detail, broadly speaking, there are three fundamentally different approaches to stratigraphic analysis: typological, architectural, and geological. There are many variations of the various systems, and any given system will usually incorporate elements of several systems, so that in practice, all three are invariably present in any given system of stratigraphic analysis, but usually one of the three approaches is dominant.

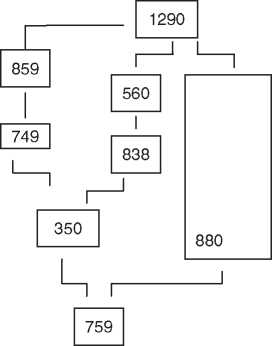

One of the most prominent typological approaches is that based on the Harris matrix. The basic conceptual idea is that excavation units are separated during excavation and become ‘stratigraphic units’ when a sequence of the excavation units is arranged in a Harris matrix (Figure 1). If each of the units is correctly recognized and separated during the excavation, and correctly labeled on the excavation drawings; the groups of artifacts are correctly tagged and the plotting of the three-dimensional positions is correct, then the objects can be assigned a specific threedimensional position which can be arranged on a two-dimensional Harris matrix. The objects recovered from the excavation thus provide a sequence which can be organized chronologically. Sections are viewed as superfluous and replaced by the Harris matrix, which is a completely logical and coherent schematic organization of the information about the sequence of units in an excavation. Since the units are not dependent upon the units drawn in sections, the goal is thus a comprehensive account of the sequence of all units without giving the inevitably misleading impression that the sequence visible in a section is somehow representative. This is important as it is a familiar fact that sections are not necessarily even representative of the sequence of layers present in the trench from which the section drawing stems. It is highly significant that although the system creates a relative chronological skeleton, minor changes can lead to entire groups of excavation units being shifted in time without any complications, meaning that the system is highly flexible. On the other hand, however, the lack of published profiles is disadvantageous since scholars have no means of assessing the reliability of the interpretations made in the field. Furthermore, the rejection of the analysis of the composition of the units means that there is no built-in deliberate effort at distinguishing floors from rubbish and collapse.

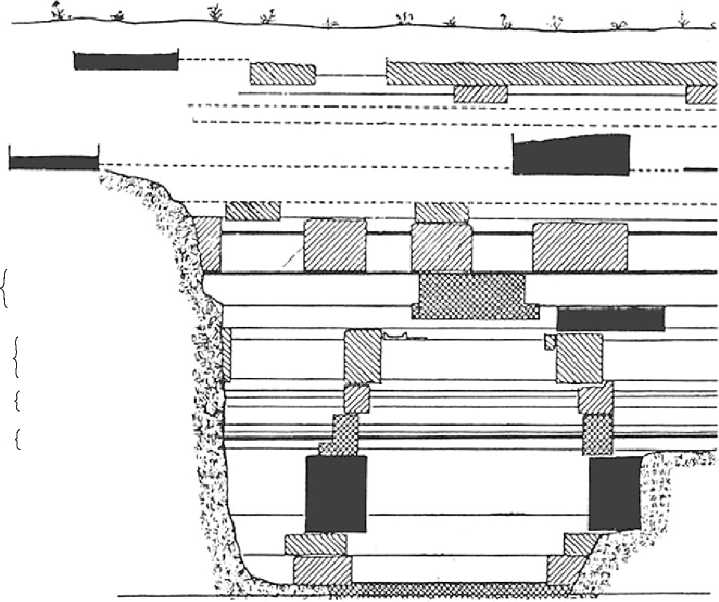

One of the most prominent architectural approaches is that developed by the German Archaeological Institute’s Oriental Department for the excavations at Uruk. Although the definitive version differs distinctly from its antecedents, the principal elements can be recognized in Koldewey’s methodology at Babylon. The basic conceptual idea is the identification of architectural sequences, with deposits and objects related to the buildings. The sequence of buildings provides the basic skeleton upon which the excavation is reconstructed. The sections stress the architectural sequence, and the layers are treated as linking the architectural features (Figure 2). History is viewed in terms of architecture, and thus the site

Comes to life through the sequence of the deliberately erected monuments (which remain in place) rather than the pottery and other rubbish (which can move through space, and thus confuse dating of layers through artifacts). However, with layers and architecture so intimately connected, even minor changes can lead to virtually irresolvable complications, which can never be resolved as both the recording and the published versions make it impossible to identify exactly what should be changed. Furthermore, the method itself makes it impossible to establish a sequence at a site if no link can be found between two buildings, as was the case at Uruk.

Figure 1 A (fictional) example of a Harris matrix applied to excavation units. The reconstruction of the stratigraphy and chronology are based upon the interpretation of the excavation units (whose relations to one another are carefully recorded during excavation, and dictate the relations between the boxes). In principle, the purpose is to assure the relative position in the sequence of the artifacts drawn from the various excavation units. In principle, no interpretation interferes with an ‘objective’ account of the relations, and these relations are based upon the excavation records. However, without published section drawings, it is impossible for an outside observer to verify the stratigraphy, and the analysis of the stratigraphic units is not the basis of the excavation, but rather the excavation units.

The strictly geological approach is still most commonly encountered in Palaeolithic excavations where the sequence of layers is virtually geological in character (i. e., devoid of architecture and very slow in terms of accumulations). However, the basic approach has been advocated for use in historical excavations as well. There are two quite different variations to the approach, one largely biblical and one largely Near Eastern.

The biblical approach was originally developed by Albright who simply adopted the geological approach used for the French Palaeolithic and applied it to the

Figure 2 An example of the architectural approach to stratigraphy: the stratigraphy of Alalakh, as presented by Sir Leonard Woolley (from D. A. Warburton, Archaeological Stratigraphy, p. 6; after L. Woolley, Alalakh, Oxford, 1955, figure 2). Stratigraphy in the sense that deposits are subordinated to the architecture.

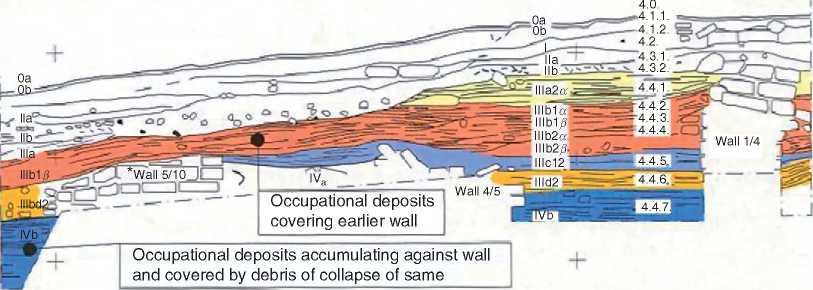

Figure 3 Example of the Near Eastern approach advocated by the author (from D. A. Warburton, Archaeological Stratigraphy, p. 59; based on D. A. Warburton in Northern Akkad Project Reports 7 (1991), plate 1). The sequence of layers (as stratigraphic units, Arabic numerals) serves as the basis for an interpretation in terms of levels (Roman numerals). The layers are linked to one another and to the architecture horizontally and vertically. In principle, an interpretation of the relations between the deposits is the precondition for the designations of the layers, and a mastery of this interpretation is the basis for the separation of the layers during excavation. The social history of buildings and neighborhoods can be followed based on the stratigraphy. The excavation units (from which objects are taken, and upon which chronological periodization depends) are identified with the stratigraphic units, and thus the typological analysis of the finds provides an independent method of using the stratigraphy.

Historical archaeology of Palestine. In this method, the objects in a layer were assigned the role of dating the layers, and thus the typology dominated the stratigraphy and the sequence was only used to coordinate the overall understanding of the site. The strength of the approach was the fact that different sites could be chronologically linked through the identification of similar artifacts, which allowed typology to be linked to both chronology and stratigraphy. The greatest weakness of the system is the dependence upon artifact classes where changes in terminology and chronology can lead to endless confusion, which again can never be resolved. Furthermore, the reliance on artifact classes leads to the creation of layers which have never been found, since their existence is postulated due to the artifacts which should be associated with them.

One of the other prominent geological approaches used for historical excavations with architecture is that developed and used by some Near Eastern archaeologists working in Iraq and Syria (including the missions of the Universities of Ghent, Louvain, Chicago, Frankfurt, and Geneva). The overriding conceptual idea is that of following the sequence of deposits, with the object of separating and analyzing the stratigraphy in the field (Figure 3). The stratigraphy is used to guide the excavation during the excavation, and the stratigraphy is also used to study the architecture, through the recognition of floors, foundation fill, debris, etc. The stratigraphic analysis is based on sections and architectural plans, and the objects are discussed in terms of stratigraphic context, understood in terms of pedological units, meticulously described in the reports. The main stress is on the link between excavations and stratigraphy. In principle, only a few archaeologists actually deny the importance of analyzing the deposits, and thus the method widely reflects an ideal shared by most field archaeologists. The greatest weakness of the approach appears to be its complicated character (and its overall intention seems to be less clear to other scholars than to the author). Furthermore, the use of a cumbrous terminology has drawn debate away from the methodology to the terminology.

Although this division into ‘schools’ is itself both arbitrary and an oversimplification, the principal differences between these schools can likewise be understood only by vastly oversimplifying. We assume that the differences can be approached by the role played by ‘layers’ or ‘deposits’. According to the Harris approach, the analysis of the deposits is of no importance: it suffices to recognize the units during excavation and to separate them. The object of an excavation is to be able to recreate a chronological sequence of such units. According to the German approach, the understanding of the layers is subordinated to the architectural sequences. The object of the excavation is the study of architecture and objects. According to the biblical approach, the layers are viewed as ‘envelopes’ containing the objects. The object of the excavation is to establish a chronological sequence based on these layers as envelopes containing objects which are diagnostic, and which can be related to historical developments. According to the Near

Eastern approach, an archaeological site consists of layers; both the excavation and the interpretation must be guided by the layers. The object of the excavation is not only to recover objects and monuments but also to understand the formation of the site both in terms of original activities and also events which took place subsequently.

In general, the approach developed by Harris has been adopted by many archaeologists, precisely because it is widely assumed that stratigraphy is primarily a chronological tool, and that the analysis of the deposits cannot usefully serve other purposes in an historical excavation. This assumption ultimately rests upon the role of stratigraphy in geology rather than its role in archaeology, and thus it fails to take account of the role that stratigraphy can play in the analysis of themes ranging from seasonal and climatic change to architectural reconstructions.

World History

World History