A distinctive group of decorated objects consists of items which were concerned with warfare, with horse-riding, chariotry or combat itself. In addition, there are objects which are not themselves part of battle regalia but which depict warriors. One group comprises actual weapons or armour which bear animal iconography in some form. The reasons for such a choice of decoration may be varied: pure design may be one, but there may also be magico-religious connotations in some instances, where the presence of the animal image itself brings luck, good fortune, protection and victory to the individual carrying an animal-ornamented sword or helmet into battle.

Swords or their scabbards were favourite subjects for zoomorphic decoration, which could be stamped or incised on the metal. A scabbard of fifth to fourth century BC date found in a grave at Hallstatt5 is ornamented with realistic figures of soldiers and horses, whose riders wear helmets, trousers and tunics and carry spears (figure 4.2). The horses themselves have haunch-spirals, an artistic device frequently employed in the treatment of animal joints and sometimes considered as being of Scythian origin. By the third century BC, zoomorphic themes were common decoration on sword scabbards. Often these take the form of birds: depictions of birds' heads adorn scabbards coming from as far apart as Cernon-sur-Coole (Marne) (figure 6.4) and Drna in Czechoslovakia; a British scabbard from the river Witham (Lincs.) is similarly decorated.6 A grave in the cemetery at Obermenzing, Bavaria, contained the burial of a man accompanied by a sword decorated with birds' heads which spring from foliate designs (figure 6.5). Despite the presence of the sword, the owner was not a warrior but a surgeon, buried with a trephining or trepanning saw (used in operations to relieve pressure on the brain) and a probe.7 The burial of a weapon with his body may mark his high status in society. A sword found at the site of La Tene itself was ornamented with three deer, tendrils of foliage hanging from their mouths, as if caught by the artist in the act of grazing. Sword-stamps in the form of boars are common occurrences, and this may well be because the boar was perceived as the spirit of aggression and invincibility.

Shields and helmets, too, carry animal designs, perhaps for apotropaic purposes. The shield from the river Witham (figure 4.18) originally bore the image of an etiolated boar on its outer surface, perhaps to protect its owner from harm. Boars were acknowledged as ferocious and

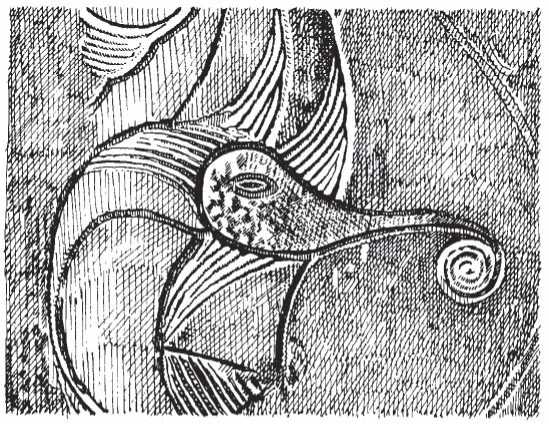

Figure 6.4 Detail of iron scabbard decorated with birds' heads, third century BC, Cernon-sur-Coole, Marne, France. Width of scabbard: 5.2cm. Paul Jenkins.

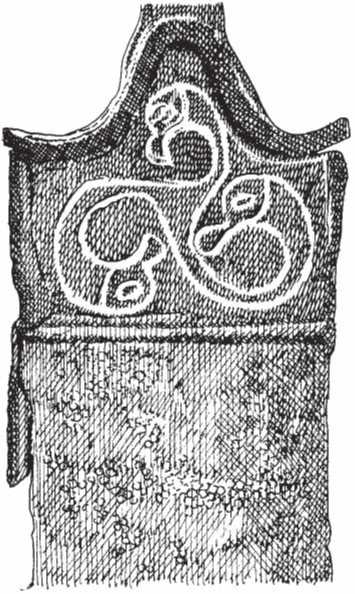

Figure 6.5 Top of iron scabbard decorated with triple bird design, c.200 BC, Obermenzing, Germany. Width c.4.8cm. Paul Jenkins.

Were often depicted as symbols of war (chapter 4); thus they were frequently present as helmet crests (see pp. 134, 152) as well as on swords and shields. Bird motifs, similar to those adorning swords, appear on the bronze bosses of two shields from the Thames at Wandsworth. Interestingly, the early Ulster Cycle saga, the 'Tain Bo Cuailnge', describes a warrior who carries a shield bearing animal designs: 'he carried a hero's shield graven with animals.'8 The zoomorphic iconography on helmets appears either engraved on the cheek-pieces or as free-standing statuettes worn as crests. An animal which is probably best interpreted as a wolf appears on the cheek-flap of a helmet from Novo Mesto in Yugoslavia, and two other helmets from this area bear crane motifs in the same position. The most fascinating animal-9 adorned helmet is the Romanian one at Ciumesti (see pp. 87-8), dating probably to the third or second century BC (figure 4.17). This is the one with the large figure of a raven crouched on the top, with hinged wings which flapped up and down when its wearer moved at speed. Whilst the iconography of the other helmets is probably present as a magical protection device, this latter represents pure aggression, designed to terrify the opponent facing the raven-bearer. It is almost certain that the raven was a Celtic battle emblem, an image of a black bird of destruction, just as it was in the early Irish written tradition (chapter 7). We know of other helmet-crests bearing animal motifs: the classical author Diodorus Siculus10 alludes to the practice among the Celts of attaching projecting animal figures to helmets. Boar and bird crests are depicted on coinage, and on the Gundestrup Cauldron11 armed horsemen are clearly shown with boars and birds attached to the tops of their helmets (figure 4.5). Perhaps, indeed, such helmets were normally worn by cavalrymen, although one of the foot-soldiers on the Gundestrup scene wears a boar-crest. The little bronze figurine of a bristling boar at Hounslow in Middlesex (figure 5.12) looks like a freestanding statuette but it was probably a helmet crest. Horns, too, adorned helmets: Diodorus mentions this, and there is the superb example of a late Iron Age horned parade helmet from the Thames at Waterloo Bridge in London (figure 4.16). Helmets carved on the first century AD arch at Orange in southern Gaul (figure 6.6) are also decorated with bulls' horns.12

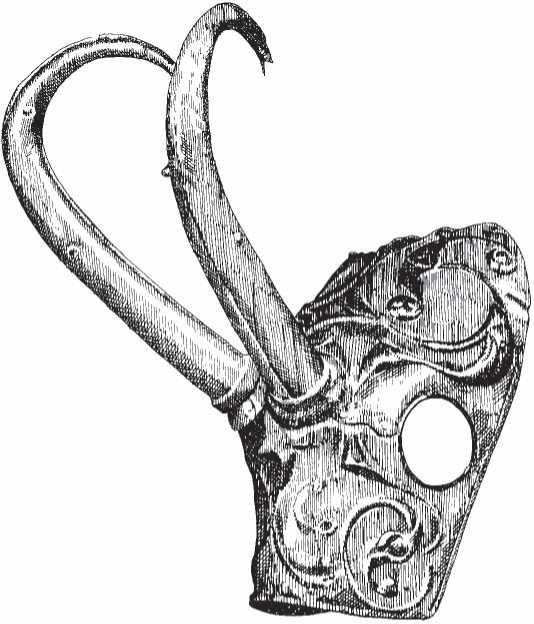

Other accoutrements of war were adorned with animal motifs: the carnyx was a long-tubed Celtic battle-trumpet, which made a fearful braying sound;13 its mouth was in the form of an open, snarling boar's head. Carnyxes are depicted on the battle scene of the Gundestrup Cauldron, carried by infantrymen (figure 4.5). The mouth of a bronze

Figure 6.6 Bull-horned helmets carved on a Roman triumphal arch at Orange, France, early first century AD. Paul Jenkins, after Ross.

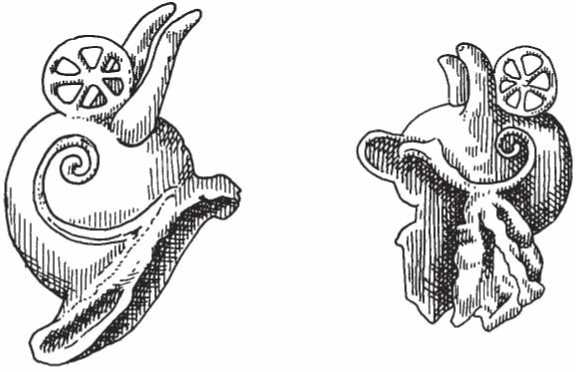

Figure 6.7 Bronze horned pony-cap, second century BC, Torrs Farm, Kelton, Scotland. Paul Jenkins.

Trumpet from Deskford, Grampian (Scotland), has been described on p. 91 (figure 4.20). Dating to the first century AD, it has a movable jaw, a vibrating wooden tongue and a pig's palate inside the mouth.14 Like the Ciumesti helmet, this implement was designed to be frighteningly realistic and to unnerve the enemy with its shrieking roar. Perhaps most curious of all objects connected with war and having artistic ornamentation is the 'pony-cap' or chamfrein from Torrs in Scotland: this is a metal mask into which two curving horns were later added (figure 6.7). The cap itself carries ornament in the form of stylized birds, and originally the horns themselves terminated in cast bronze birds' head. Professor Martyn Jope has suggested15 that the Torrs mask was worn not by a horse for protection in battle but by a human, presumably in some kind of shamanistic ritual. Professor Jope points to the 'hobby-horse' figure on the Aylesford Bucket, which is not a real horse because the legs bend the wrong way and are clearly those of two men in a horse-costume, perhaps performing in some religious 'pantomime'.

Horse harness was sometimes decorated with zoomorphic designs. Two back-to-back bulls' heads with knobbed horns adorn the bronze rein-ring at Manching (figure 2.4). The pair of first century AD splay-legged bull figures with curled-up tails from the Bulbury (Dorset) hillfort (figure 7.13) were perhaps fittings for a chariot or cart: the curved tails are so designed as to function as rein-guides, and each leg is pierced for attachment to wood.16

Depictions of warriors on horseback frequently decorate Celtic metalwork: this is particularly apparent in the Hallstatt Iron Age, where cavalry riding ithyphallic horses adorn such sheet-bronze objects as the bucket-lid at Kleinklein in Austria (figure 4.3). A brooch from Numantia in Spain is in the form of a mounted warrior (figure 4.7), a severed head beneath the horse's chin.17 The little figure of a rider in sheet-bronze from a chariot-grave at Karlich in Germany was probably applied to a vessel or fitting. There are horsemen images on one of the plates of the Gundestrup Cauldron, and they are frequent on coins.18

World History

World History