African cattle The ongoing discussion about cattle

Domestication in Africa envisions the existence of an indigenous species, Bos opisthonomous, froh the domesticated form have originated.

Alternately pivoting stamp technique Pottery decoration technique realized with a comb impressed into the clay and lifted alternately on the extremities of the edge.

Bucrania (sing. Bucranium) From greek boVg (cow) and Xpaviov (skull).

Pisci Building material composed mainly of mud or clay not molded in bricks.

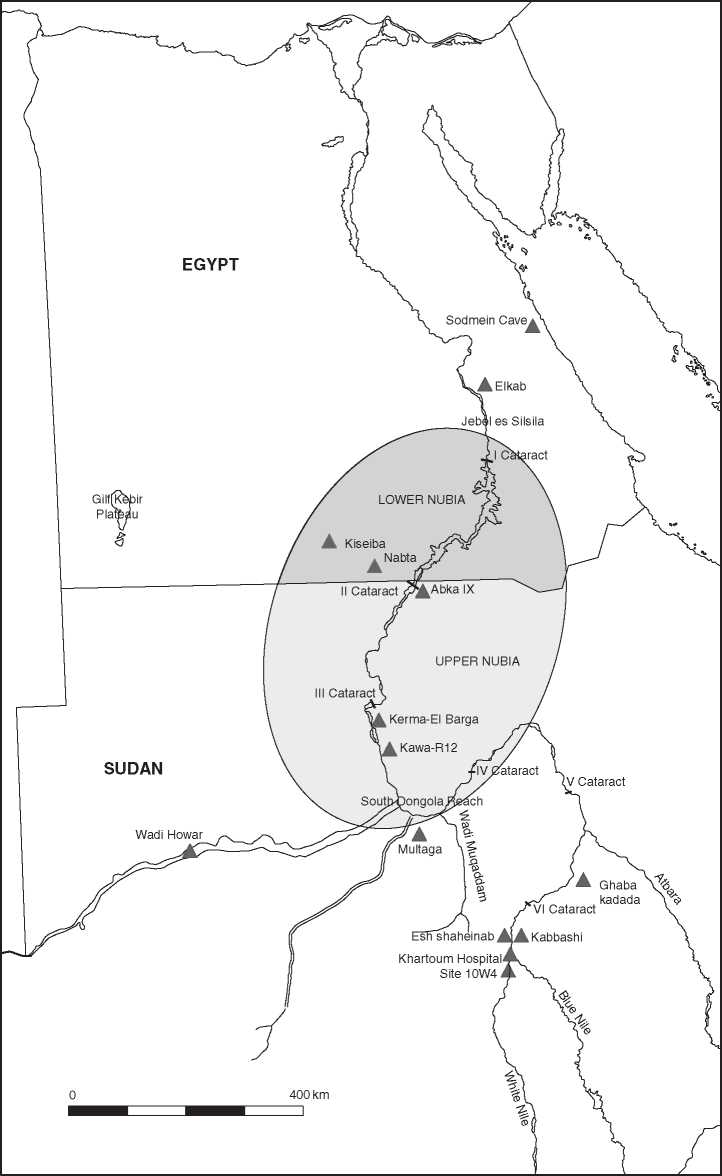

The Nubian contribution to the Nile Valley cultural development has been considered, for quite a long time, secondary to that of Upper and Lower Egypt (Figure 1). Nineteenth - and twentieth-century scholars, strongly influenced by the size and extent of archaeological remains scattered along the Nile, regarded Nubia, at the southern periphery of the Egyptian world, only as ‘a corridor’ to Africa. This ‘middle-land’ was, in fact, the theater for remarkable cultural changes that preluded to the formation of complex societies and were the precursors of the later urban pharaonic theocracy (see Africa, North: Egypt, Pre-Pharaonic).

For a more detailed geographic description of the area a distinction between Egyptian and Sudanese Nubia seems to be appropriate. Egyptian Nubia, or Lower Nubia, encompasses the area from Jebel es

Figure 1 Location map of sites mentioned in the text. © 2008 Donctella Usai. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Silsila to the frontier between Egypt and Sudan, or the II Cataract, and the Sudanese Nubia, or Upper Nubia, from the II Cataract to the Southern Dongola Reach. It is from the core of this region that new archaeological

Data arrive which motivated new thoughts on the overall Nile Valley recent prehistory cultural sequence.

The Mesolithic is a key period in the prehistory of man, one when the seeds of the transition from a

Hunting-gathering-fishing economy to food production were laid down.

Among the archaeological evidence left by Near Eastern Mesolithic communities are the first permanent structural remains, sometimes related to ritual activities, and faunal assemblages bearing the earliest evidence of domesticated species and cereals remains produced by more systematic gathering activities. This evidence may be interpreted as the beginning of a process that will produce a fully Neolithic economy.

The Nile Valley was and is still considered to be peripheral to the areas where this process took its first steps but, without denying a possible contribution to the neolithization of Nile Valley coming from Near Eastern regions, it seems that also Mesolithic Nubians were involved in a process of social and economic changes evidenced, apparently, by successful animal domestication.

The Mesolithic population, in Nubia as well as in Central Sudan, is made up by hunter-gatherer-fisher communities that were producing pottery vessels some centuries before their appearance in the Near East where a Pottery Neolithic dates to around 6800BC.

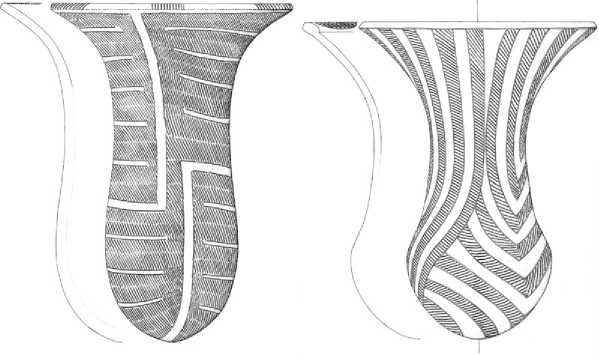

The first discovery of Mesolithic pottery in the Sudanese Nile Valley was made by A. J. Arkell at the Mesolithic site of Khartoum Hospital. Two types of decoration, among others, characterize Mesolithic pottery production: incised Wavy Line (Figure 2) and impressed Dotted Wavy Line (Figure 3). During the years of the Nubian Salvage Campaign (1960-1968) a site, Abka IX, with ‘similar’ material was found also in Nubia and radiocarbon dated 8260 ± 400 BP. At the time the date was considered too old and rejected because of the high range, but recent archaeological discoveries in much more controlled contexts proved its being reliable. It is now accepted that a ceramic Mesolithic culture behind regional character was widespread along the Nile Valley and adjacent areas, from Central Nubia down to Central Sudan and further south, during the VIII-VII millennium BC. Nothing which can firmly be related to this culture has been found, until now, in the Upper and Lower Egyptian Nile Valley, neither in the adjacent deserts and oases. A VII millennium BC site, Elkab, located in the Nile Valley, between Luxor and Aswan, produced a lithic industry with an Epipalaeolithic character, some bone tools but no pottery.

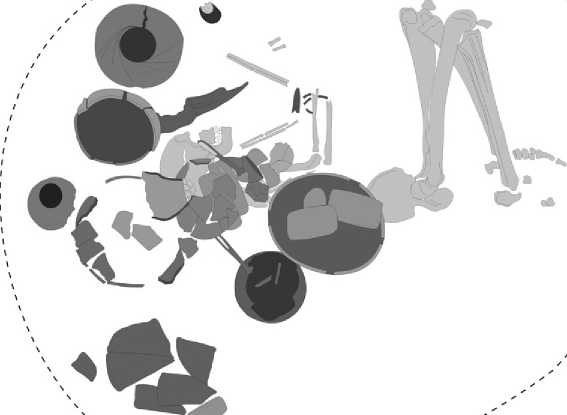

The adoption of pottery technology within Sudanese Mesolithic societies has been correlated with an increased sedentary lifestyle. Until recently no evidence, other than the pottery itself, suggested such a reduction in mobility. Most Mesolithic sites along the Nile Valley have been, in fact, deeply affected by postdepositional natural and human disturbances. Nevertheless, very recent and still largely unpublished excavations revealed semi-subterranean huts at El Barga, in the Kerma Basin, at a seasonal Late Mesolithic site near Khartoum (Figure 4) and pise walled dwellings at a VII millennium BC Mesolithic settlement along the left bank of White Nile again south of the Sudan capital.

Nile river-versus-desert seasonal movements and vice versa were practiced by the Mesolithic hunter-gatherer-fishers at the beginning of the Early Holocene when, according to palaeoenvironmental data, deserts, to the west and the east of the Nile, became less inhospitable with the formation of many seasonal water pools.

Figure 2 Sample of Early Mesolithic potsherds with typical Wavy Line incised decoration, realized with a Nile catfish spine. © 2008 Donctella Usai. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Figure 3 A fragment of Late Mesolithic pottery decorated with Dotted Wavy line impressed pattern. This decoration is realized with the alternately pivoting stamp technique. © 2008 Donctella Usai. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Figure 4 Excavation at a Late Mesolithic prehistoric seasonal camp south of Khartoum. The site, 10-W-4, revealed a series of semisubterranean huts with refusal pits. © 2008 Donctella Usai. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

The pioneering researches conducted by F. Wendorf at Nabta Playa and Kiseiba Plateau sites in the Western Desert, 100 km to the west of the Nile, at the height of the II Cataract, produced the most interesting, although debatable, data concerning these Mesolithic groups. The structures excavated at these desert sites, and the faunal and palaeobotanical assemblages suggest that strictly scheduled seasonal movements may have provided a semi-sedentary life in a sort of residential mobility congruent with pottery production.

Fishing activity, whose practice is strongly evidenced especially in Mesolithic Central Sudan sites, may also have encouraged a less mobile lifestyle. Demographic growth may also have been responsible for an increased territorial control and, as a consequence, of less mobility.

It is important to underline that, as suggested for the Near Eastern Mesolithic societies, this increased sedentary way of life may have favored experimentation in animal domestication, as in the case of the

African cattle. Most reliably these first experiments took place in Nubia at the end of the Vlll-beginning of the VII millennium BC. The first evidence for cattle domestication comes from different sites in the Nabta-Kiseiba Western Desert. Few fragments of possibly domesticated cattle recovered at these sites date to the beginning of the VIII millennium BC. Some scholars reject this ancient occurrence, for different reasons, not least the questionable contextual associations. The presence of a few domestic cattle bones at Western Desert sites led the excavators to speak of an Early Neolithic phase, but the overall faunal assemblage is made up of wild species suggesting more caution is necessary.

However, evidence of domestic cattle was recently found in Sudanese Nubia, in the Kerma Basin, at the Mesolithic site of El Barga and dated to the VII millennium BC.

Domestic sheep and goat appeared in the Nile Valley and in Nubia later on, around the VI millennium BC, as witnessed by sites like Sodmein cave in the Red Sea Mountain, Nabta-Kiseiba, in the Western Desert, and El-Barga, in the Kerma Basin. As it is genetically proved that sheep and goats originate in the Near East, it is probably here that we have to envisage influences from outside the valley.

Cattle herding became increasingly important in Nubian societies; hence, pastoralism became the basic subsistence economy of these populations.

The emergence of cattle domestication seems limited, up to now, to the Nubian region. No evidence has been produced by sites along the Nile Valley north and south of Nubia. Moreover, no evidence of this kind was produced by the many prehistoric sites located in the desert north and south of the Nabta/ Kiseiba region.

Central Sudan societies seem to retain their hunting-gathering-fishing economy until the middle of the

V millennium BC.

When the first Neolithic groups appear in Central Sudan (see Africa, Central: Sudan, Nilotic), they show a material culture which displays strong similarities with that produced by Nubian groups whose socioeconomic structure had already changed to a pastoral one more than a millennium before. If this picture will be confirmed by future archaeological investigations it will be interesting to work out whether the long-lasting Mesolithic social and economic way of life in Central Sudan has been culturally or environmentally determined. Palaeoenvironmental studies documented a climatic deterioration around the VI millennium BC. It affected firstly the Nubian region and only many centuries later the Central Sudan and may have produced, at the same time, an acceleration in subsistence economy transformation in Nubia as well as favoring the maintenance of the hunter-gatherer-fisher subsistence model of Central Sudan Mesolithic populations. At present the Early Neolithic of Central Sudan seems to correspond to the Middle Neolithic of Nubia (Figure 5).

Some of the social and cultural aspects of these

V and IV millennium BC Neolithic groups are so similar that there is no wonder that all along the valley there were strong and permanent interrelations.

Figure 5 Nubian and Central Sudan chronological sequence according to new data provided by recent excavations in the region. © 2008 Donctella Usai. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Figure 6 One of the richest graves excavated at the Middle Neolithic cemetery R12, in Lower Nubia, close to the Egyptian town of Kawa. The body, of an adult male, was covered by 108 objects. © 2008 Donctella Usai. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Figure 7 A sample of valuable stone axes recovered at R12 cemetery. © 2008 Donctella Usai. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Figure 8 Tools made from animal bones or containers made from a hippopotamus tooth are very common at Middle Neolithic Nubian cemeteries. © 2008 Donctella Usai. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Figure 9 Caliciform beakers are considered ritual containers as they have been found only in cemeteries. They are characteristics of Nubian and Central Sudan Neolithic. © 2008 Donctella Usai. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Nubia’s Neolithic is known mainly from the excavation of few of the many mound-like burial grounds dotting the Nubian landscape. These cemeteries produce the image of a ranked society with some form of incipient elite. A few graves (Figure 6), in each cemetery, are accompanied by an exceptional number of objects: pots, stone axes, mace-heads, ivory bracelets, necklaces made of semiprecious stone beads, containers made from hippopotamus teeth and bucrania (Figures 7 and 8). The number of bucrania varies according to the individual’s social position, whether achieved or acquired though kin relationship. Red and yellow ochre was often used to cover the body, which sometimes lay on an animal skin. Some graves also contain complete skeletons of an ovicaprine.

One pot, in particular, seems to have had a ritual character. It is the caliciform beaker (Figure 9). This container, decorated in different ways, probably according to different regional tastes, is present only in grave contexts.

Many of the Nubian Neolithic settlements, seemingly, were destroyed by erosion or Nile flooding. They appear, in fact, as dense scatters of archaeological material. The lack of structural remains at Neolithic sites, in contrast with the evidence provided by hundreds of burial grounds sometime of very large size, has been considered as attesting the high mobility of these Neolithic herders and their living in rather ephemeral dwellings. However at Kerma, an extensive excavation revealed the structural organization of a Neolithic village, dating to 4500 BC, witnessed by thousands of postholes. While no stratified deposits survived at the site the study of postholes distribution has made possible the reconstruction of the plan of an otherwise lost ancient and complex settlement.

See also: Africa, Central: Sudan, Nilotic; Africa, North: Egypt, Pre-Pharaonic; Sahara, Eastern; Animal Domestication.

World History

World History