The Hongshan Culture of China consisted of small villages occurring about every 10 kilometers on either side of the Yingjin River and connected by a network of paths through the forests. They were probably a sheep-oriented culture, since by this time, sheep-tending had inflltrated its way eastward from Mongolia and Central Asia. Pigs had by this time also been domesticated. Pigs became to the early Chinese what the bear was to the Siberian hunters, namely a ritual animal, and this largely because of its human-like attributes.

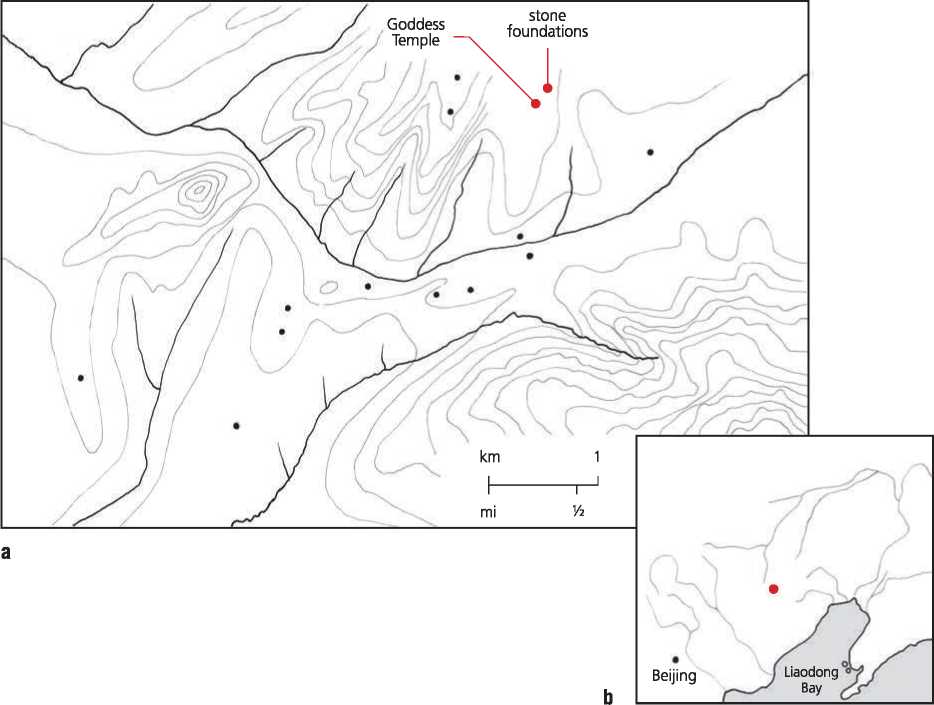

Hongshan houses were square to rectangular in shape, with sides ranging from 4 to 12 meters and were multi-family dwellings. Though the culture was organized into farmstead communities, there were no nucleated hamlets or villages, but rather dispersed aggregations of houses on slopes above the rivers. Each community had its own ceremonial facility25 (Figure 7.33a, 7.33b, 7.33c).

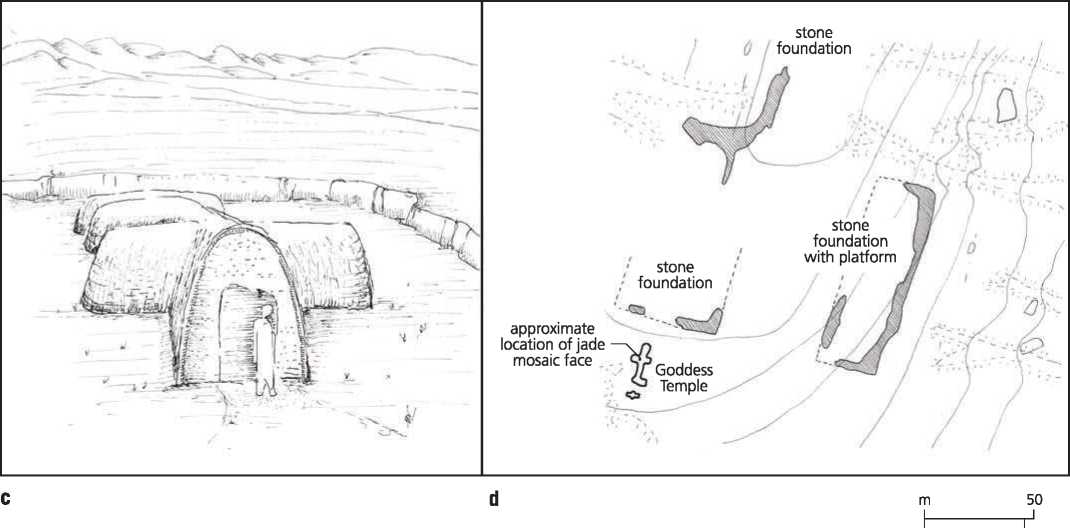

Figure 7.33a, b, c, d: (a) general territory showing archeological sites; (b) map; (c) possible reconstruction; (d) site plan. Source: Timothy Cooke/Information from Sarah Milledge Nelson

One of these, Niuheliang, was particularly impressive, consisting of at least fourteen burial mounds, altars, and platform areas spread out over several hills.26 It dates from around 3500 bce but could have been founded even earlier. There is no evidence of village settlements nearby, and yet its size is clearly much larger than one clan or village could support. In other words, though rituals would have been performed here for the elites, the large area implies that this was a regional center attracting supplicants from far afield. A key building was a structure that is presumed to have been a Goddess Temple. Sited at near the top of the hill, it was about 25 meters long and about 2 meters wide. Two lobes branched os' symmetrically about a third of the way from the entrance with one asymmetrical lobe at the rear. The walls, made of loam reinforced by a web of branches, lean toward each other to form a type of tunnel, maybe around 3 meters high at its apex. From its footings we know that the walls were ornamented with elaborate geometric designs made with clay in high relief and painted yellow, red, and white. Near the northern end of the tunnel, archaeologists uncovered parts of a clay figure, including a head, torso, and arms, with jade eyes as well as a shoulder and breasts. As the name of the site suggests, the statue was interpreted by the excavators as a representation of a goddess. But it would be a mistake to assume that this was a deity in the modern sense. It was most probably a guardian figure. Furthermore, the structure was most certainly not a temple since it could not hold many people. It was probably a charnel house, where the dead were stored until the time of a secondary burial, with the statue not so much a deity as a protector. To the south of this structure there was an oval building of unknown purpose, and to the north overlooking the temple a large platform where ceremonial sacrificial activities took place. Pig remains have been found throughout the site, and probably were an important element in the sacrifices. 27

Many of the Niuheliang tombs are surrounded by broken pottery cylinders, thousands of them, in fact. These cylinders were open at both ends and served as drums with hide stretched over the openings. In shamanistic terms they were used to communicate with the spiritual world.28 Jade was also associated with shamanistic rituals as it facilitated the connection between the deceased. A jade bird, for example, was found under a skull in one burial. The making of jade objects was carried out on a large scale by the Hongshan. Where the jade came from has not been determined, possibly from the north Changbaishan region some 500 kilometers to the east, meaning that it was acquired through trade.29

At the entrance to the Niuheliang valley there is an artificial hill, with a ring of squared, white stones encircling its base. Another ring of white stones is embedded in the middle of the height of the mound, and a third was placed near the top. Artifacts found near the top of the mound include crude clay crucibles used for smelting copper. Since the top of a hill is a surprising place to melt copper, the structure seems to have been meant for ritual events involving smelting.30

At another site, a tomb of a shaman priest, dating from about 4000 bce, was found in the shape of a single, squarish room with a lobed space at the rear. The man’s grave was located under the pounded earth floor. His body was flanked by two animals, both painstakingly and beautifully made by means of hundreds of shells. One is of a tiger and the other is of what has been labeled a dragon (Figure 7.34). It has been suggested, however, that at this time in history, mythological figures would have been inconsistent with shaman imagery, and so what is depicted is an alligator. Such animals were known to exist in the region at that time, especially since it was both warmer and wetter than today. The two animals facing away from the body and their heads pointing northward as if walking next to him represent the realms of earth and water.31

World History

World History