The renowned paleoanthropologists Louis and Mary Leakey began their search for human origins at Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania, because of the presence of crude stone tools found there. The tools were found in deposits dating back to very early in the Pleistocene epoch, which began almost 2 mya. The oldest tools found at Olduvai Gorge defined the Oldowan tool tradition.

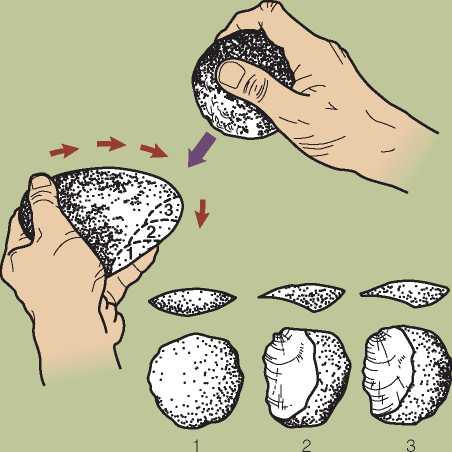

These earliest identifiable tools consist of a number of implements made using a system of manufacture called the percussion method (Figure 8.1). Sharp-edged flakes were obtained from a stone (often a large, water-worn cobble) either by using another stone as a hammer (a hammerstone) or by striking the cobble against a large rock (anvil) to remove the flakes. The finished flakes had

Figure 8.1 By 2.5 million years ago, early Homo in Africa had invented the percussion method of stone tool manufacture.

This technological breakthrough, which is associated with a significant increase in brain size, made possible the butchering of meat from scavenged carcasses.

Sharp edges, effective for cutting and scraping. Microscopic wear patterns show that these flakes were used for cutting meat, reeds, sedges, and grasses and for cutting and scraping wood. Small indentations on their surfaces suggest that the leftover cores were transformed into choppers for breaking open bones, and they may also have been employed to defend the user. The appearance of these tools marks the beginning of the Lower Paleolithic, the first part of the Old Stone Age.

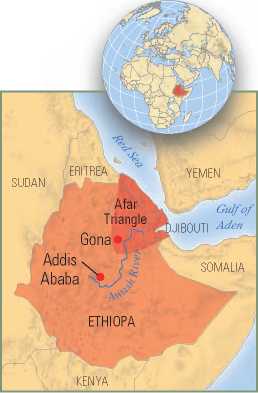

The tools from Olduvai Gorge are not the oldest stone tools known. Paleoanthropologists have dated the start of the Lower Paleolithic to between 2.5 and 2.6 mya from similar assemblages recently discovered in Gona, Ethiopia. Lower Paleolithic tools have also been found in the vicinity of Lake Turkana in northwestern Kenya, in southern Ethiopia, as well as in other sites near Gona in the Afar Triangle of Ethiopia. Before this time, tool use among early bipeds probably consisted of heavy sticks to dig up roots or ward off animals, unshaped stones to throw for defense or to crack open nuts, and perhaps simple carrying devices made of knotted plant fibers. Perishable tools are not preserved in the archaeological record.

The makers of these early tools were highly skilled, consistently and efficiently producing many well-formed sharp-edged flakes from available raw materials with the least effort.106 To do this the toolmaker had to have in mind an abstract idea of the tool to be made, as well as a specific set of steps to transform the raw material into finished product. Furthermore, the toolmaker would have to know which kinds of stone have the flaking properties that would allow the transformation to take place, as well as where such stone could be found.

Sometimes tool fabrication required the transport of raw materials over great distances. Such planning for the future undoubtedly was associated with natural selection favoring changes in brain structure. These changes mark the beginning of the genus Homo. As described in the previous chapter, Homo habilis was the name given to the oldest members of the genus by the Leakeys in 1959. With larger brains and the stone tools

The oldest stone tools, dated to between 2.5 and 2.6 mya, were discovered in Gona, Ethiopia, by Ethiopian paleoanthropologist Sileshi Semaw.

Preserved in the archaeological record, paleoanthro-pologists began to piece together a picture of the life of early Homo.

World History

World History