The relationship of the hunter to his prey is equivocal and ambiguous: this is reflected in some of the iconography. There is no doubt about the desire of the hunter to overcome and kill his quarry. But there is also respect and the animal must in some manner consent to its death in order that the harmony of nature be maintained. So the weapons would have to be made in the correct manner and the right rituals observed. This is exactly the kind of attitude to wild animals displayed in the hunting communities of the North American Indians. This may be why some of the hunter-gods depicted in Celtic iconography display a close, even tender relationship between hunter and hunted: the Touget huntsman113 carries his hare in his arms, not by the ears or slung over his shoulder. The hunter at the Vosges sanctuary of Le Donon rests his hand affectionately on the antler of the stag standing fearlessly next to him.114

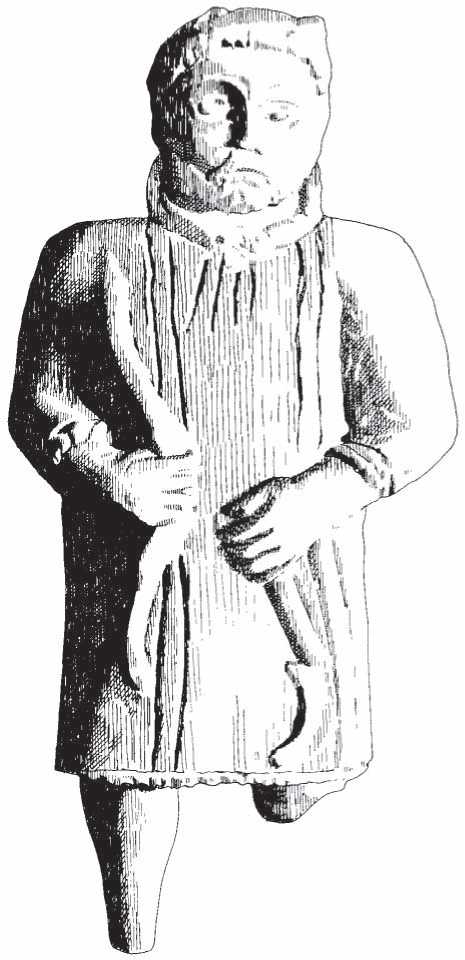

Figure 3.12 Stone figure of a horned hunter-god with tore, bow and billhook Romano-Celtic date, La Celle-Mont-Saint-Jean, Sarthe, France. Paul Jenkins.

Classical sources, the vernacular Welsh and Irish tradition, archaeozoological evidence and iconography all make a very positive and direct link between hunting and the supernatural. Religion and the hunt were closely associated. Killing wild animals was dangerous, an activity which required the will of both the victim and the gods. The hunter needed to protect himself from his prey and also from the risk of unbalancing nature by taking a life. Hunters entered into a kind of relationship with their quarry, and because the slaughter of animals was sometimes necessary in order that a community might survive, the hunt itself became a composite symbol of death and resurrection or regeneration. There was thus a seemingly direct exchange of life for death.115 Arrian states that ancient Celts never went on hunting expeditions without the blessing of the gods.116 In a sense, hunting itself was a form of ritual activity which needed both permission and assistance from the divine powers.117 Since hunting could be either for sport or for food, the hunter-deities could themselves be associated with war or with abundance. Arrian's comments on the attitude of the Celts to hunting make it clear that the activity was perceived as a theft from the natural world: thus hunting had to be redeemed by a reciprocal payment, a life for a life. So Arrian explains that hunting cult-practices consisted of payment made in the form of offerings in respect of the different creatures hunted. The wealth thus annually accumulated was used to buy a domestic animal to sacrifice to the supernatural powers. Arrian alludes to a hunter-goddess to whom this sacrifice was made, together with the first-fruits of the hunt, on the occasion of the goddess's birthday. This account of hunting sacrifice is interesting: in order to fulfil the 'life for a life' bond, a domestic beast was exchanged for a wild one. Perhaps the deity regarded this as a more valuable offering than one of her own wild creatures. The necessity, in religious terms, of substituting one life for another is described elsewhere of humans, by Julius Caesar, who speaks of the Gauls' habit of sacrificing humans in time of war.118

There are other literary allusions by Graeco-Roman commentators concerning hunting and the gods. Like Arrian, Diodorus Siculus119 refers (indirectly this time) to the offering of the first-fruits of the hunt, when discussing the Celtic practice of offering up the decapitated heads of their enemies to the gods: 'they nail up these first fruits (severed heads) upon their houses, just as do those who lay low wild animals in certain kinds of hunting.' Strabo120 describes a horrific form of Celtic human sacrifice, whereby huge wicker images of men were built, filled with humans, cattle and different species of wild beast (presumably specially caught for the purpose), and burnt as sacrificial offerings.

Though the archaeozoological or faunal evidence of wild animal remains from Celtic Iron Age sites is so sparse, certain deposits are closely associated with ritual (see chapter 5). Sanctuaries like that at Gournay, with their evidence for ritual feasting, are significantly lacking in the bones of wild beasts, indicating perhaps a deliberate avoidance of such creatures as religious food. But one sanctuary, Digeon (Somme), does show evidence of ritual activity which was specifically associated with wild creatures. The most spectacular behaviour represented at this shrine concerned the apparent massacre of a number of stags in order to make use of the skullcaps with antlers attached.121 If the interpretation of this evidence is correct, then it looks as if the head and antlers could have been worn, perhaps in fertility or hunting ceremonies, where a shaman-priest dressed up as a deer in order magically to attract the herd and promote a successful hunting expedition.

In Britain, wild animals were associated with ritual shafts and pits.122 A pit at Newstead in southern Scotland contained sets of antlers, deliberately placed there as if for a religious purpose.123 Two pits at Ipswich in Suffolk each contained a piece of hare fur; a ritual shaft at Ashill, Norfolk, contained a deposit of antlers, pots and boar tusks;124 and there are other examples of this kind of functionally inexplicable behaviour. In Romano-Celtic Chelmsford, a young boar was buried entire, perhaps as a foundation-offering, to bring good luck to a building; at Sopron in Hungary, an Iron Age ritual deposit contained a complete boar, packed into a stone-lined grave.125

The supernatural element in hunting is prominently displayed in the iconography of the Celtic Iron Age and Romano-Celtic period. The veneration of an essentially rural people for the natural world manifests itself in art, where motifs and designs based on deer, boars and birds abound. Boar images are particularly common as figurines or as war emblems (see chapter 6).126

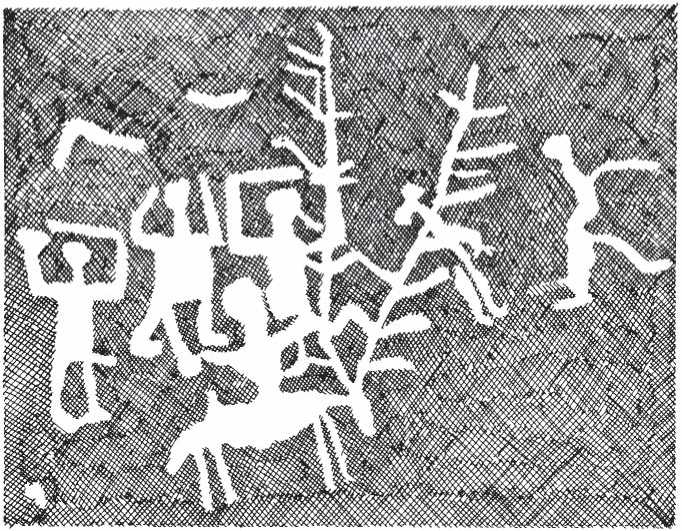

The imagery of Camonica Valley is particularly rich in hunting symbolism. Stags are depicted with immense antlers, perhaps evocative of supernatural status; the hunted stag was a divinity as well as prey. In the Bronze Age, the Camunian stag-god appears in the rock art as a god of hunting. The divine stag, worshipped in its own zoomorphic form during this period, was semi-anthropomorphized in the Iron Age. The ambiguity of hunted animal as god is easy to comprehend in the terms of the ambivalent attitude towards the hunt already discussed. The victim might evoke feelings of both veneration and guilt at the taking of a life from wild nature. On one image at Naquane, one of the main group of Camunian images, a set of armed figures dances round a large stag which stands before a temple. The stag is perhaps about to be killed by a hunter-spirit.127 On another scene, people surround and pray to a huge stag accompanied by other deer of 'normal' size.128 The implication is that the bigger animal is divine. This apotheosis is demonstrated still more strongly by a third representation which portrays a creature that is in semi-human, semistag form, with enormous tree-like antlers (figure 3.13).129

Figure 3.13 Rock carving of a god in the form of a half-human, half-stag figure, Camonica Valley, north Italy. Paul Jenkins.

What of the hunter-gods themselves? The images we have depict divine huntsmen who in some ways closely resemble human hunters. But in other respects there must be differences. The Touget hunter is naked, as is the Merida boar-hunter; this would not be a sensible way of going to the hunt especially if he were facing dangerous game. But Celtic warriors sometimes fought naked, and there may thus have been a close symbolic link between hunting and warfare. The god at Touget carries a hare, which perhaps he had killed with the sword hanging at his belt, and the large hound at his side perhaps flushed out the prey from cover. The accoutrements of the Le Donon god are similarly significant. He is armed with lance, knife and chopper; his mastery over the forest is demonstrated by his clothing - his wolfskin cape and his boots, which are decorated with the heads of small animals. His stag quarry stands next to him. In Britain, the god Nodens at Lydney may have been a hunter: he was equated on dedications with Silvanus, the Roman woodland god, and one of the offerings at his shrine was a model of a hunting-dog.130 At the Nettleton Shrub (Wilts.) temple,131 the presiding god was Apollo Cunomaglus (Hound-Lord), implying the presence of a hunting cult; Apollo had a role as a huntsman in classical mythology. In north Britain, Cocidius was worshipped as a local huntergod, often depicted with horns to demonstrate his affinity with the animal world.132 It is interesting that Cocidius could be equated both with Silvanus and with Mars, thus showing the very close link perceived to pertain between war and hunting.

The vernacular Welsh and Irish myths show very clearly the close relationship between the hunt and the supernatural (see also chapter 7). In these myths there are countless allusions to hunting, usually as an activity of nobles. Hunters frequently have encounters with beings from the Otherworld. Thus in the Mabinogi, Pwyll meets Arawn, king of Annwn, while both are out hunting. Again, Manawydan and Pryderi are hunting in Dyfed when they and their dogs meet an enchanted boar from the Otherworld.133 In Irish mythology, such heroes as Finn and Cu Chulainn hunt magic boars and stags which entice them to the realms of the supernatural powers. Sometimes these animals are emissaries, but on occasion they are gods transformed into animal form.134 Flidhais, an Irish goddess of wild things, including deer, may have been a divine huntress, like Arduinna and the Roman Diana. Certainly the Welsh Mabon, in 'Culhwch and Olwen', is a hunter-god.135 The idea seems to have been that the divine hunt brought not simply death and the end but immortality through the act of shedding blood. Certainly in the myths, a blow can be the catalyst which transforms an animal back to its original human form. It may be the case that the mythology which associates superhuman heroes with the hunt reflects the archaeological evidence, with its scarcity of faunal remains relating to hunting activity. Accordingly, at least some hunting may have been strictly the preserve of noblemen. Equally, hunting may have been hemmed round by bonds, taboos and rigid rules. Because hunting was a serious matter, involving the destruction of part of nature, it may have been perceived as an activity in which the gods must play the key role.

World History

World History