Yearly meets between peoples, usually during late fall and winter, are common among the peoples of the Great Continuum since they reaffirm the network of social relations that bond people and clans together. In Alaska and among Northwest Coast people, these meets developed into a complex culture of gift: giving, known collectively as the potlatch, usually held in December and January aft:er the seasonal stores were established. There are difierent names for these events, but in the late nineteenth century they became known collectively as potlatches, a word derived from Chinook trade jargon and brought north by prospectors.

During a potlatch neighbors and nearby villagers would be invited for days or even weeks of feasting, gambling, and dancing. People congregated in a large house or village kazhium (ceremonial house, or qasxiq) to tell of their ancestors and of hunting expeditions (Figure 5.22). Women oft:en spent months making headdresses or clothing to be worn during these festivals. At the end of the potlatch these adornments were destroyed as a means of thanking the guests for the honor of their presence. The garments would be cut up and the pieces distributed to the guests. Sometimes even the ceremonial houses were destroyed if they were built for the occasion.

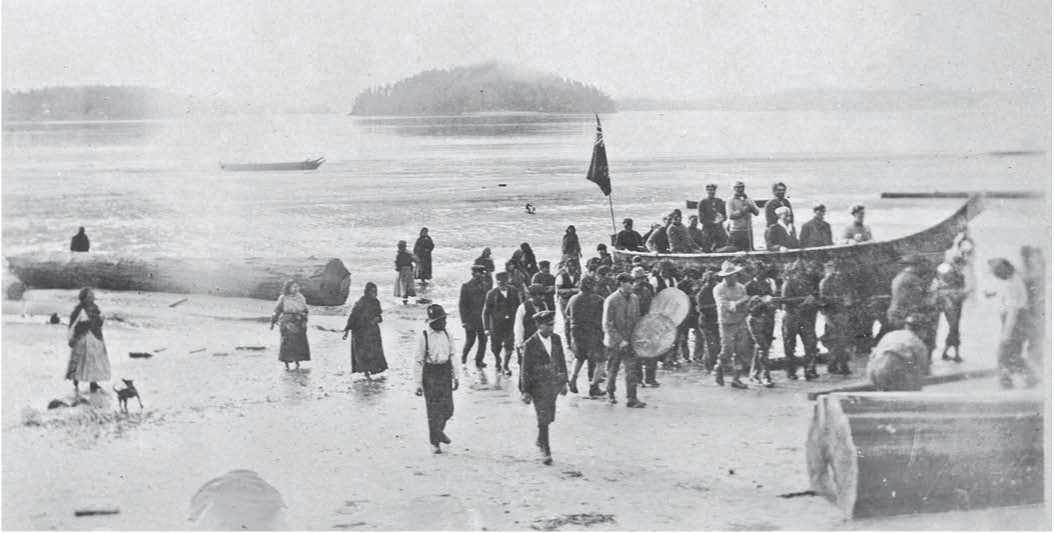

Figure 5.22: Guests arriving for a potlatch at Opitsat, Chilkat River, Alaska, 1895. Source: Courtesy of Royal BC Museum, BC Archives

The following is adapted from a description of 1916:

A line of 26 dog teams stretched across the Tanana River, advanced a few hundred feet, stopped and advanced again. The hosts lined the bank over-looking the river. The red and blue sashes of the men and feathered headdresses of the women, decked with ribbons of all colors, flashed against the backdrop of snow. Now and then a volley of rifle shots was flred and answered by a return fusillade from the travelers. When not flring their rifles those on the bank sang songs accompanied by the beat of a drum. Now the teams have all reached the Nenana side of the river, some two hundred yards from where the songs of welcome are being sung. Chief Evan of Coschaket and Chief Alexander of Tanana gather their men and women in a group and advance in close formation. With the long line of women and children left: on the bank, still singing, the Nenana men march down to the river.

They too form a group and when then near they rushed toward each other, cheering as they come. But they did not rush up to one another and shake hands. They passed by each other, turn and pass again. Finally, the visitors rushed up on the bank and danced about among the crowd gathered there. Then there was a brief pause. The visitors drew up in a line, and were given a short address of welcome by Chief Thomas of Nenana. This was responded to by Chiefs Evan and Alexander. This over, the guests went to the “big house,” and afl:er a dance came out and then began to shake hands. Each night a lavish feast was served to the guests, who were seated on the floor in long lines. They drank sweetened tea, and ate boiled meat, sweetened biscuits, and rice boiled with dried apples and raisins. While they ate people sang continually. Afl:er the feast one of the potlatch hosts gathered about him a group of the people and began a dirge for the departed. Afl:er the singing of several of these dirges over and over again, the mourning dance would begin. These were organized with the men standing together in one part of the hall and the women lined up against the wall swayed their bodies from side to side to the rhythm of the song. People sang about a moose hunt and a squirrel jumping from tree to tree. On the last night the potlatch hosts brought blankets, clothing, guns and other useful gifts to the “big house” and made of it a big pile in the center of the room. Seated about on the floor, people waited patiently for something to be thrown to them by the potlatch man or his helper.15

Early descriptions tend to emphasize the free-spirited nature of these events and can miss the point that individuals were supposed to guard themselves during a potlatch by following certain precautions and acting in a restrained manner. The host should be careful how he boasts of his wealth, and the guests careful they do not covet that wealth. If people act greedy, or in an egocentric manner, or are careless, they become vulnerable to supernatural forces that could harm or even kill them. If, on the other hand, they refrain from excess, they will live a long life.

Potlatches came in different sizes. Whereas large ones brought together entire communities, small ones commemorated a young person’s first harvest, a young woman’s first menses, or the death of an infant. Larger ones were held at the death of an older person, or to commemorate a person’s recovery from a severe illness or accident, all involving the distribution of food and gifi:s. The size of a potlatch also depended on the age and social status of the individual for whom the potlatch was given. Community or clan leaders received big potlatches.

World History

World History