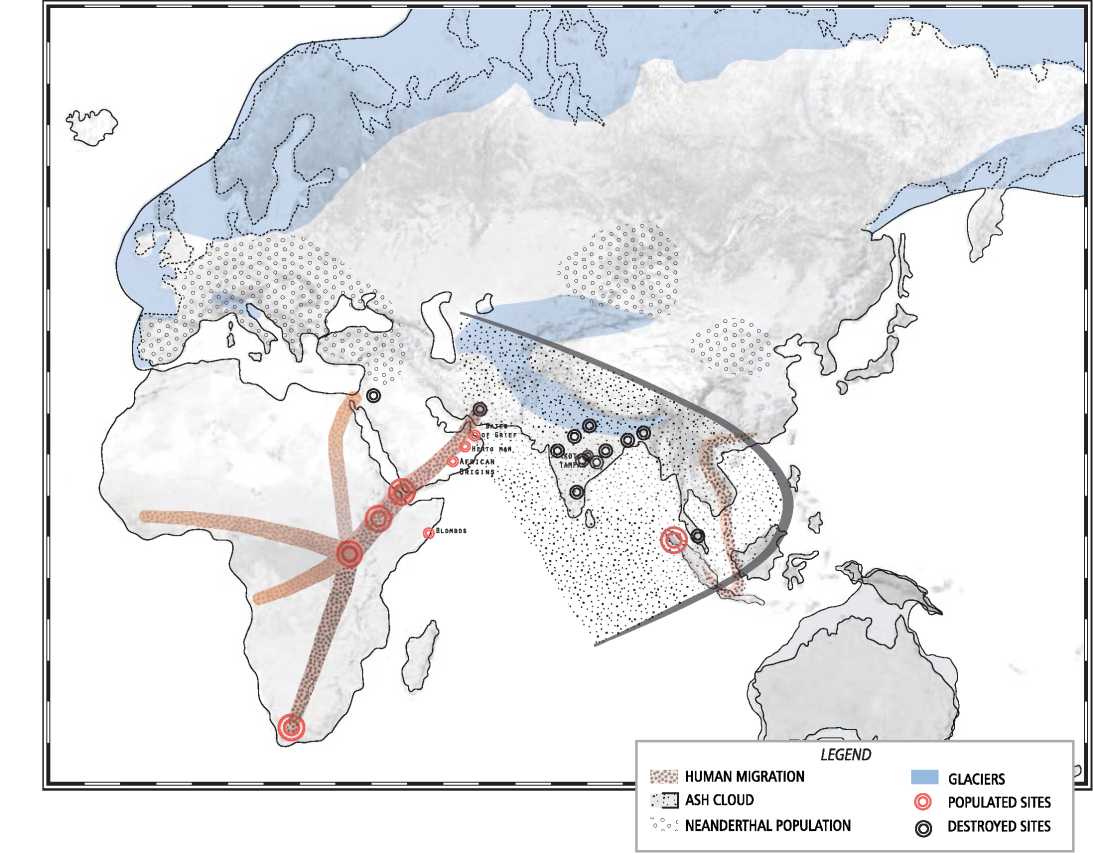

Figure 1.19: Mt. Toba eruption. Source: Florence Guiraud

Following the path of the Homo erectus, humans worked their way into Arabia. Once again, it is important to remember that climactic conditions back then were much different than today. The sands of the Rub’ Al Khali Desert in Saudi Arabia, which stretch over 700 kilometers east to west, were once the bottom of lakes and marshlands. Between the southern edge of that area and the ocean, there was a corridor in Yemen and Oman in which archaeologists have already discovered dozens of ancient settlements. From there, people made it into Iran where there were seveal extensive wetlands and around the coasts of India, and by 80,000 bce had moved into Indonesia. But around 70,000 bce, disaster struck; the Toba Volcano on the island of Sumatra erupted (Figure 1.19). It was one of Earth’s largest cataclysms, laying down several meters of ash over India and parts of South Asia and producing a six-year global volcanic winter. The famous Mt. Vesuvius or even the eruption of Mount St. Helena would be pinpricks in comparison. The stratospheric layer of dust and debris that covered the planet left its traces even in Greenland. Unfortunately for Homo sapiens and the residual populations of Homo erectus in India, the geographical distribution of people at that time ensured almost maximum possible exposure to the effects of the explosion. The populations in India and Indonesia were wiped out. Even the people who lived in the Levant and West Asia seem to have vanished. A subsequent thousand-year ice age did not help. So devastating were these events that it has been estimated

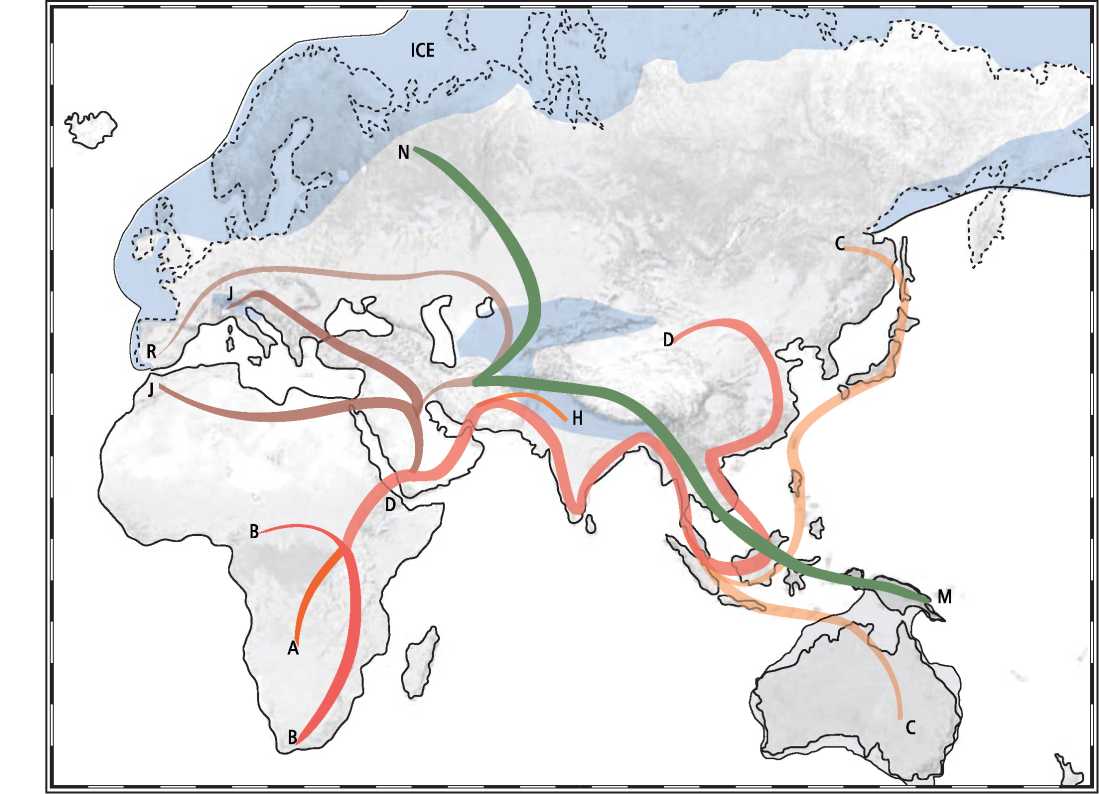

That the global population was reduced to as few as ten thousand people or fewer living in isolated pockets mostly in eastern and southern Africa—in other words, back where they started. 35 The process of leaving Africa began again and this time it would succeed. In fact, Homo sapiens would inherit the earth as the residual strands of Homo erectus died out one by one. This means that every one of us is a genetic relative of these first people in southern Africa. Geneticists know this because of haplogroup studies. A haplogroup is a type of genetic package, the oldest being Haplogroup A, which belongs to the! Kung who live in the Kalahari Desert in Botswana (Figure 1.20). They are, at any rate, its last remnants. By the time people had expanded again into east Africa, we see the emergence of Haplogroup C and because it was these people who then left Africa around 60,000 bce, Haplogroup C became the common male ancestor of nearly all people living today who have non-African roots. Haplogroup C people were shore - and water-oriented and would eventually work their way to Australia and then around the Pacific to form the basis of some of the Native American genetic stock. Haplogroup D, which also formed in East Africa and is equally as old as Haplogroup C, is found today at high frequency among populations in the Japanese Archipelago and the Andaman Islands, though curiously not in India, perhaps because India and central Asia were already dominated by Haplogroup F people. This genetic strand developed around 50,000 bce, not in Africa but probably in India and was the center of a dispersion cloud that radiated northward into Asia. Facilitating this movement was a dramatic warming of the climate during the period 55,00045,000 bce that allowed people to return to the Levant after an absence of 40,000 years. From

Figure 1.20: Africa and Eurasia: The major haplogroups. Source: Florence Guiraud

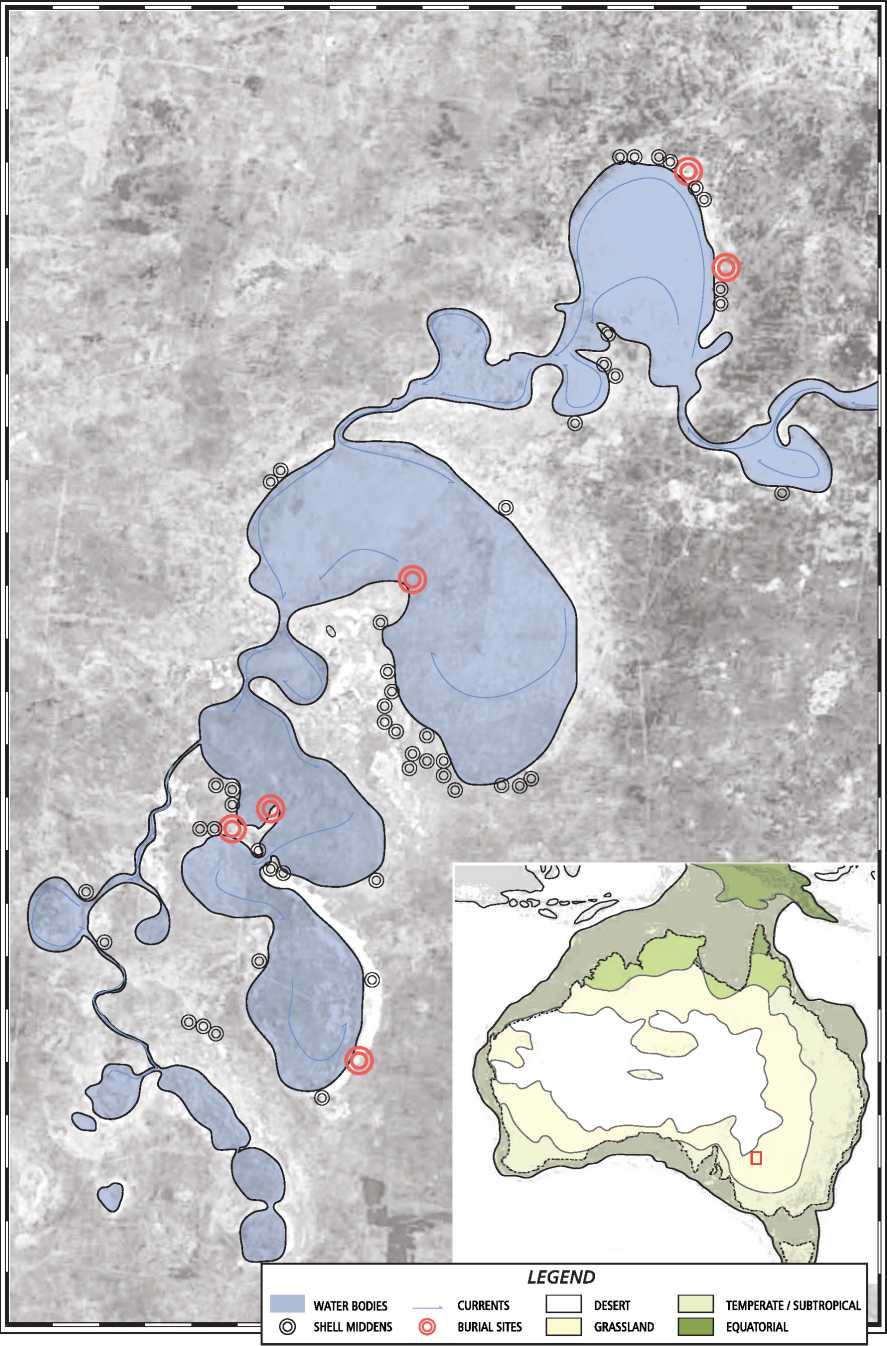

Figure 1.21: Willandra Lakes area. Source: Florence Guiraud

There, humans encountered a vast stretch of semi-arid, grass-covered plains stretching from eastern France to Korea that allowed movement throughout Asia, yielding new haplogroups such as K, I, J, O, and others. Humans were spreading so quickly and over such a diverse geographical range that no single natural disaster could now impede their progress.

33 21 20 S, 143 08 55 E

Australia, which became home to Haplogroup C people around 42,000 bce, or perhaps earlier, was the most enticing of human habitats at that time.36 People there encountered astounding and unfamiliar animals: marsupial lions, two-meter-long goannas, short-faced kangaroos (procoptodon), and the rhinoceros-sized, though harmless, diprotodon. The latter two were herbivores and were thus tempting prey for the humans, who may indeed have contributed to their extinction.37 Though the continent was relatively arid, it was cooler and moister than today. Rains brought a good deal of water to the eastern shores, water that was funneled by mountains into west-flowing rivers and streams, producing broad woodland belts and lower down large stetches of savanna. Glaciers in the mountains produced a constant stream of summer run-ofil49 The rivers fed dozens of lakes, now known as the Willandra Lakes (Figure 1.21).

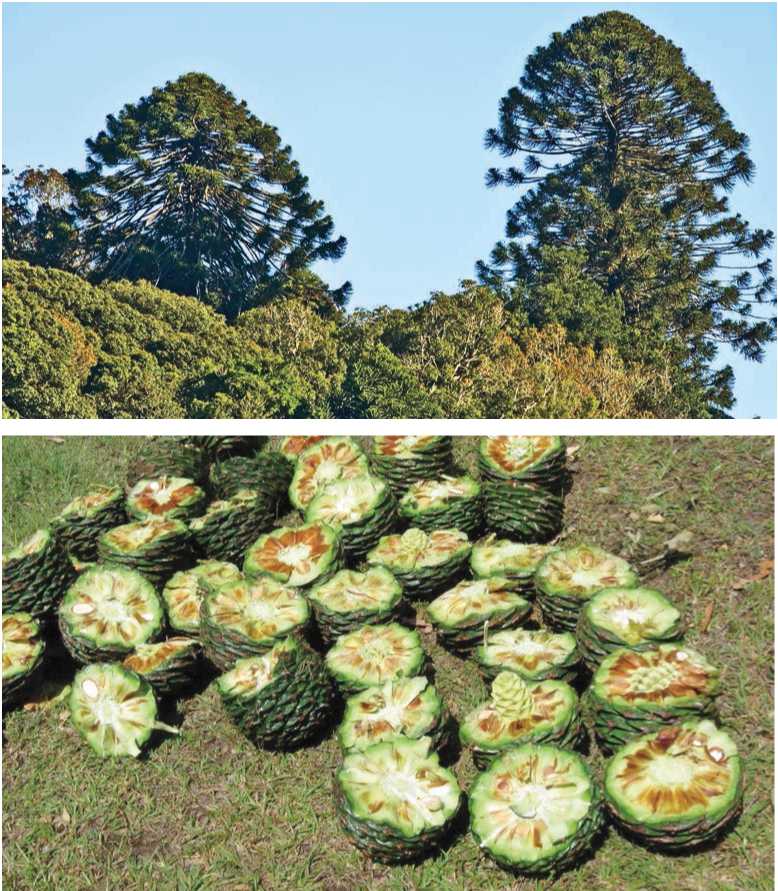

These lakes, which reached their highest level some 35,000 years ago and which today are nothing but dried-out sand pits, were situated between low ridges just to the north of a vast marshy area. They teemed with flsh and mussels that were caught with nets and apparently transported in baskets.38 In fact, the heaps of discarded shells (called shell middens) are the clues indicating that humans once lived in what is today a forbidding desert.39 A wide range of nut trees grew in the temperate forests along the mountain slopes to the east, including the majestic Bunya pine (Araucaria bidwillii) that is still considered a sacred tree by the indigenous people (Figure 1.22 and 1.23). It produces cones about the size of a football, each containing

Figure 1.22: Bunya Pine forest, Australia. Source: Marie Read

Figure 1.23: A Bunya Pine cone, Australia. Source: Steve Swyane

From fifty to a hundred nuts. Highly nutritious and an excellent source of starch, they can be eaten raw or roasted and have a taste similar to chestnuts. All in all, this was not a place where humans eked out a minimal existence a few steps away from starvation. Food and water were plentiful. From the footprints of adults and children preserved in the once muddy shores that have since hardened into rock, we know that adults were tall, on average 180 centimeters (5 foot 11), no doubt due to the plentiful and varied food supply.40

As one might expect, this also was a place of ceremony and ritual. A burial near one of the lakes contained the remains of a woman who had first been cremated, then her bones were smashed and the fragments placed in a pit in the center of a fire for renewed burning. The whole was then covered with sand. Another burial contained a man whose bones had been stained with red ochre. We even know some of the places where the ancient Australians mined their ochre, namely in the northern Flinders Ranges some 200 miles to the west where, for millennia, people extracted not only hematite (red), but also magnetite (brown to black), goethite (yellow), and lepidocrocite (yellow).

World History

World History